By Eric Vandenbroeck

The tribulations and consequences of the Treaty of

Versailles

Opened on 28 June

2019 the exhibition

in Arras organized by the Palace of Versailles starts with the proclamation

of the German Empire in the same Hall of Mirrors that witnessed the signing of

Peace of Versailles on 28 June.

The year 1919 was, in

fact, a catalytic moment not only did it see already earlier the rise of

Mussolini, in March 1919, but 51 representatives from two dozen countries also

met in Moscow at the Founding Congress of the Communist International. Long

before Versailles, the other great totalitarian ideology of the 20th century,

Marxism-Leninism, was also on the march.

When Germany signed

the armistice ending hostilities in the First World War

on November 11, 1918, its leaders believed they were accepting a "peace

without victory," as outlined by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson in his

famous Fourteen

Points.

Thus during the first

six months of 1919, after more than four years of an unprecedentedly miserable

and destructive war, global statesmen traveled to Paris in the hope of creating

a permanent peace. The leaders of the victorious Allies, including US president

Woodrow Wilson, British prime minister David I Loyd George, and French premier

Georges Clemenceau, lived in the same city for nearly six months along with the

representatives of many other allied and neutral nations. They met in various

forums both official and informal on a nearly daily basis.

But the world was to

discover that making peace endure was a matter not just of hopes and ideas but

of will, determination, and persistence. Leaders need to negotiate as well as

to inspire; to be capable of seeing past short-term political gains, and to balance

the interests of their nations against those of the international community.

For want of such leadership, among other things, the promise of 1918 soon

turned into the disillusionment, division, and aggression of the 1930s.

This outcome was not

foreordained at Versailles. Although some of the decisions made upon ending the

war in 1919 certainly fueled populist demagoguery and inspired dreams of

revenge, the calamity of World War II owed as much to the failure of the

democracies’ leaders in the interwar decades to deal with rule-breaking

dictators such as Mussolini, Hitler, and the Japanese militarists. A century

later, similar forces - ethnic nationalism, eroding international norms and

cooperation, and vindictive chauvinism - and authoritarian leaders willing to

use them are again appearing. The past is an imperfect teacher, its messages

often obscure or ambiguous, but it offers both guidance and warning.

The price of peace

"Making peace is

harder than waging war," French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau

reflected in 1919 as the victorious powers drew up peace terms, finalized the

shape of the new League of Nations, and tried to rebuild Europe and the global

order.

For Clemenceau and

his colleagues, among them Wilson and David Lloyd George, the British prime

minister, the prospect was particularly daunting. Unlike in 1815, when

negotiators met in Vienna to wind up the Napoleonic Wars, in 1919 Europe was

not tired of war and revolution. Nor had aggressor nations been utterly

defeated and occupied, as they would be in 1945. Rather, leaders in 1919

confronted a world in turmoil. Fighting continued throughout much of eastern

Europe, the Caucasus, and the Middle East. Russia's Bolshevik Revolution of

1917 had apparently set off a series of unstoppable revolutionary waves that

threatened to overwhelm even the victors' societies.

The war had damaged

or destroyed old political and social structures, particularly in Central

Europe, leaving formerly stable and prosperous peoples adrift, desperate for

someone or something to restore their status and a form of order. Ethnic

nationalists seized the opportunity to build new countries, but these states

were often hostile to one another and oppressive to their own minorities.

Inevitably, too, old and new rivalries came to the surface as leaders in Paris

maneuvered to promote the interests of their nations.

Wilson and company

also had to deal with a phenomenon that their forerunners at the Congress of

Vienna had never had to consider: public opinion. The public in Allied

countries took an intense interest in what was happening in Paris, but what

they wanted was contradictory: a better world of the Wilsonian vision, on the

one hand, and retribution on the other.

Many Europeans felt

that someone must be made to pay for the war. In France and Belgium, which

Germany had invaded on the flimsiest of pretexts, the countryside lay in ruins,

with towns, mines, railways, and factories destroyed. Across the border, Germany

was unscathed, because little of the war had been fought there. The British had

lent vast sums to their allies (their Russian debts were beyond hope of

recovery), had borrowed heavily from the Americans, and wanted recompense.

John Maynard Keynes,

not yet the world-renowned economist he was to become, suggested that the

Americans write off the money the British owed them so as to reduce the need to

extract reparations from the defeated and then concentrate on getting Europe�s

economy going again. The Americans, Wilson included, rejected the proposal with

self-righteous horror. And so the Allied statesmen drew up a reparations bill

that they knew was more than the defeated could ever pay. Austria and Hungary

were impoverished remnants of a once vast Habsburg empire, Bulgaria was broke,

and the Ottoman Empire was on the verge of disintegrating. That left only

Germany capable of meeting the reparations bill.

A rude awakening

The circumstances of

Germany's defeat had left its citizens in no mood to pay. That feeling would

grow stronger over the decade to follow. And its outcome contains a warning for

our era: the feelings and expectations of both the winners and the losers, however

unrealistic, matter and require careful management.

Toward the end of the

war, the German High Command under Generals Erich Ludendorff and Paul von

Hindenburg had effectively established a military dictatorship that kept all

news from the front under wraps. The civilian government in Berlin knew as

little as the public about the string of defeats the country's military

suffered in the late spring and summer of 1918. When the High Command suddenly

demanded that the government immediately sue for an armistice, the announcement

came like a thunderbolt.

The German chancellor

appealed to Wilson in a series of open letters, and the U.S. president,

somewhat to the annoyance of the European Allies, took on the role of arbiter

between the warring sides. In doing so, Wilson made two mistakes. First, he

negotiated with Germany's civilian government rather than the High Command,

allowing the generals to avoid responsibility for the war and its outcome. As

time went by, the High Command and its right-wing supporters put out the false

story that Germany had never lost on the battlefield: the German military could

have fought on, perhaps even to victory, if the cowardly civilians had not let

it down. Out of this grew the poisonous myth that Germany had been stabbed in

the back by an assortment of traitors, including liberals, socialists, and

Jews.

Second, Wilson's

public statements that he would not support punitive indemnities or peace of

vengeance reinforced German hopes that the United States would ensure that

Germany was treated lightly. The U.S. president's support for the revolution

that overthrew Germany's old monarchy and paved the way for the parliamentary

democracy of the Weimar Republic compounded this misplaced optimism. Weimar,

its supporters argued, represented a new and better Germany that should not pay

for the sins of the old.

Many Europeans felt

that someone must be made to pay for the war, but the circumstances of

Germany's defeat had left its citizens in no mood to pay.

The French and other

Allies, however, were less concerned with Germany's domestic politics than with

its ability to resume fighting. The armistice signed in the famous railway

carriage at Compiègne on November 11, 1918, reads

like a surrender, not a cessation of hostilities. Germany would have to

evacuate all occupied territory and hand over its heavy armaments, as well as

the entirety of its navy.

Even so, the extent

of the military defeat was not immediately clear to the German public. Troops

returning from the front marched into Berlin in December 1918, and the new

socialist chancellor hailed them with the words "No enemy has overcome

you." Apart from those living in the Rhineland on the western edge of the

country, Germans did not experience firsthand the shame of military occupation.

As a result, many Germans, living in what Max Weber called the dreamland of the

winter of 1918-19, expected the Allies' peace terms to be mild-milder,

certainly, than those Germany had imposed on revolutionary Russia with the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918. The country might even expand if

Austria, newly formed out of the German-speaking territories of the vanished

Austro-Hungarian Empire, decided to join its fate to Germany's.

Asia and the dilemma over

Shandong

The Paris Peace

Conference had a significant impact on Asia. Prior to the war, the Western

powers exercised imperialistic control over most of Asia. Britain controlled

modern-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar, along with Hong Kong and

Singapore. France controlled modern-day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Russia

took territory in Northern China; the Netherlands had Indonesia; the United

States controlled the Philippines.

China and Japan were

the only real significant independent Asian countries before the war. But China

was on the verge of losing its independence. The British, French, Germans, and

Russians all exercised control of territory in China via concessions. But Japan

was China's greatest threat. Before the war, Japan had already taken Taiwan and

Korea from China, and they controlled Manchuria. The First World War halted

European expansion in China, but this left Japan unchecked to wrest away more

Chinese territory.

Japan entered the war

on the side of the Allies. Before the war, Germany had control of islands in

the Pacific, and Japan took these islands during the war. Germany had

controlled a territory in China called Shandong, and Japan seized these German

concessions. The Japanese made secret imperialistic agreements with Britain

during the war that would allow them to keep the German Pacific islands and

Shandong.

The Japanese had two

demands at the Paris Peace Conference. First, they wanted the Allies to uphold

their secret wartime agreements on Shandong and the German Pacific islands.

Second, they wanted a racial equality clause. In other words, the Japanese desired

a clause in the peace treaty stating that Europeans and Asians are of equal

racial quality.

Like the Japanese,

the Chinese joined the war on the side of the Allies. The Chinese believed that

contributing to the war effort would prevent the Europeans and Japanese from

expanding in China after the war. China had one major demand at the Paris Peace

Conference: Shandong. This territory had a large Chinese population, and it was

culturally important because it was the birthplace of Confucius. But the

British had promised Shandong to the Japanese. The Allies found themselves in a

dilemma over Shandong.

According to the

principle of national self-determination, the Chinese had the proper claim to

Shandong. Sadly, the principle of imperialism prevailed over the principle of

national self-determination. The peacemakers upheld their imperialistic wartime

agreement and granted Shandong to the Japanese instead of the Chinese.

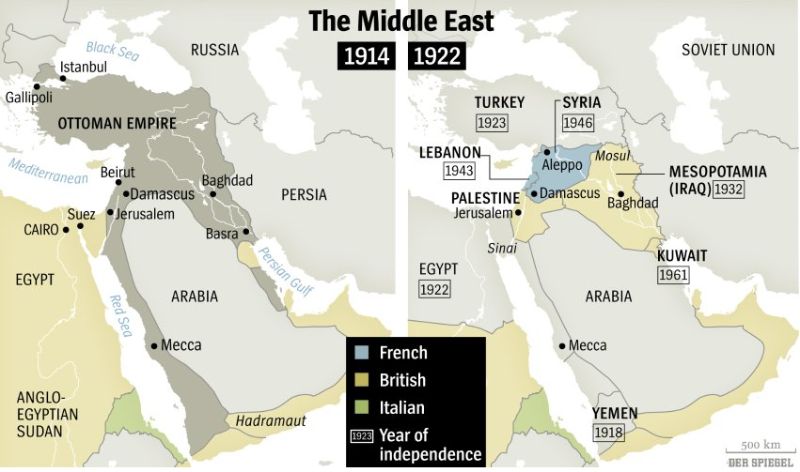

The Middle East

The geopolitical

situations in the Middle East over the last century have

their roots in the First World War and the Paris Peace Conference. Before

the war, the British controlled Egypt, the French controlled Algeria and

Tunisia, and Italy controlled Libya. By contrast, the Ottoman Empire controlled

modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia.

At the beginning of

the war, the Allied Powers made secret agreements to carve up the Ottoman

Empire. For their part in the war, the Russians demanded the expansion of its

territory down to Constantinople. This was a sensitive issue for the British,

for it would give Russia influence in the Mediterranean waters around the Suez

Canal. India was the jewel in the crown of the British Empire, and Britain

shuttled their troops to India through the canal. In short, the Suez Canal was

essential to Britain�s imperial control over India.

The British would

agree to the Russian demand for Constantinople, but only if Britain was

guaranteed certain territory around the Suez Canal. This territory included

modern day Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and southern Iraq. British control of these

territories would create a bubble around the Suez Canal and thereby secure the

British route to India.

The Sykes-Picot

Agreement of January 3, 1916 was a secret treaty

between Britain and France to carve up the Middle East after the war.

France would get the territory of modern day Syria, Lebanon, and northern Iraq,

while Britain would get the territory of modern day Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and

southern Iraq. Later, the Russians and Italians assented to the treaty.

Unfortunately, the

British made promises to the Arabs inside the Ottoman Empire that were

incompatible with Sykes-Picot. The British and French controlled territory in

India and North Africa that contained vast numbers of Muslims. The British and

French were terrified that the Turkish sultan would incite Muslim revolts

inside their empires. They were desperate to knock the Ottomans out of the war

to avoid an Islamic uprising.

British military

campaigns against the Ottomans were disastrous. As a result, the British devised a plan to destabilize the Ottoman

Empire from within. The plan was to have the Arabs revolt against the

Turks. The British promised Hussein, the Sharif of

Mecca, that he would be made king of a unified and independent Arab state after

the war if he revolted against the Turks. Hussein agreed. His son Faisal,

advised by Lawrence of Arabia, led the Arab revolt against the Turks. The Arab

revolt thus played a role in the collapse of the

Ottoman Empire.

At the peace conference, the British broke their

promise to establish a unified and independent Arab state. Instead, they

created a handful of new nations in the Middle East that would be dominated by

Britain and France. In 1921, the French created the Kingdom of Syria. The British

convinced the French to make Faisal the ruler of Syria, but he had no

independence. He was exiled by the French in July 1920. The French created the

state of Lebanon in 1920, and transferred territory from Syria to Lebanon. This

act of imperialism still irritates Syrians today.

The Sykes-Picot

Agreement led to the creation of Iraq. According to Sykes-Picot, the British

would get Baghdad and Basra, while the French would get Mosul in the North. The

British realized the importance of oil much earlier than the French, and the

British suspected there was oil in Mosul. In 1918, the British convinced the

French to relinquish their claim to Mosul. In this way, the British took control of the entire territory that is

now Iraq. The British formed the Kingdom of Iraq in 1921, and Faisal was

made king.

The British promise

for an independent Arab state was incompatible with Sykes-Picot. But British

promises to European Jews further complicated the situation in the region. On

November 2, 1917, the British government issued the

Balfour Declaration - a public statement supporting a homeland for the

Jewish people in Palestine. Czarist Russia was the great anti-Semitic power

before the war, and this made many Jews reluctant to support the Allies. The

English believed the Balfour Declaration would foster Jewish support of the

Allies and weaken Jewish support for the Central Powers.

Sykes-Picot gave the British control of Palestine. In 1921, the

British carved Jordan out of Palestine and made Hussein's son Abdullah king.

However, the creation of Jordan infuriated both the Jews and the Arabs. On the

one hand, the Jews thought the Balfour Declaration granted them the entire

territory of Palestine. Thus, they viewed the creation of Jordan as a broken

promise.

When the Treaty came

as a shock

The actual Treaty of

Versailles, published in the spring of 1919, came as a shock. Public opinion

from right to left was dismayed to learn that Germany would have to disarm,

lose territory, and pay reparations for war damage. Resentment focused in

particular on Article 231 of the treaty, in which Germany accepted

responsibility for starting the war and which a young American lawyer, John

Foster Dulles, had written to provide a legal basis for claiming reparations.

Germans loathed the "war guilt" clause, as it came to be known, and

there was little will to pay reparations.

Weimar Germany-much

like Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union-nursed a powerful and

lasting sense of national humiliation. For many years, the German Foreign

Office and its right-wing supporters did their best to further undermine the

legitimacy of the Treaty of Versailles. With the help of selectively released

documents, they argued that Germany and its allies were innocent of starting

the war. Instead, Europe had somehow stumbled into a disaster, so that either

everyone or no one was responsible. The Allies could have done more to

challenge German views about the origins of the war and the unfairness of the

treaty. Instead, at least in the case of the English-speaking peoples, they

eventually came rather to agree with the German narrative, and this fed into

the appeasement policies of the 1930s.

Critics of Versailles

got their attack in early. Just six months after the treaty was signed John

Maynard Keynes published “The Economic Consequences of the Peace”, the book

that made his name. Today however Keynes’s critique of the Treaty of Versailles

is seen as problematic. In fact, Keynes himself

shortly after stated that he regretted having written the book.

Keynes himself

regretted it, and so should historians and economists today. Mentioned in an

article early in 2017 telling to me was that sometime in 1936, after the March

29 “election” in Germany which consolidated Hitler’s power, Elizabeth Wiskemann, a German-born, Cambridge-educated historian, met

[Keynes] at a social gathering in London. Suddenly, she reported later, she

found herself saying, “I do wish you had not written that book [meaning The

Economic Consequences of the Peace, which the Germans never ceased to quote],

and then longed for the ground to swallow me up. But he said simply and gently,

‘So do I.’” (1)

Peace would take a

very different form in 1945. With memories of the previous two decades fresh in

their minds, the Allies forced the Axis powers into unconditional surrender.

Germany and Japan were to be utterly defeated and occupied. Selected leaders would

be tried for war crimes and their societies reshaped into liberal democracies.

Invasive and coercive though it was, the post-World War II peace generated far

less resentment about unfair treatment than did the arrangements that ended

World War I.

Missed opportunities

The terms of

Versailles were not the only obstacle to a lasting resolution of European

conflicts in 1919. London and Washington also undermined the chances for peace

by quickly turning their backs on Germany and the rest of the continent.

Although it was never

as isolationist as some have claimed, the United States turned inward soon

after the Paris Peace Conference. Congress rejected the Treaty of Versailles

and, by extension, the League of Nations. It also failed to ratify the

guarantee given to France that the United Kingdom and the United States would

come to its defense if Germany attacked. Americans became all the more insular

as the calamitous Great Depression hit and their attention focused on their

domestic troubles.

The United States'

withdrawal encouraged the British-already distracted by troubles brewing in the

empire-to renege on their commitment to the guarantee. France left to itself,

attempted to form the new and quarreling states in Central Europe into an anti-German

alliance, but its attempts turned out to be as ill-fated as the Maginot Line in

the west. One wonders how history might have unfolded if London and Washington,

instead of turning away, had built a transatlantic alliance with a strong

security commitment to France and pushed back against Adolf Hitler's first

aggressive moves while there was still time to stop him.

London and Washington

undermined the chances for peace by quickly turning their backs on the

continent.

Again, the post-1945

world was different from the one that emerged in 1919. The United States, now

the world's leading power, joined the United Nations and the economic

institutions set up at Bretton Woods. It also committed itself to the security

and reconstruction of western Europe and Japan. Congress approved these

initiatives in part because President Franklin Delano Roosevelt made building

the postwar order a bipartisan enterprise-unlike Wilson, who doomed the League

of Nations by alienating the Republicans. Wilson's failure had encouraged the

isolationist strain in U.S. foreign policy; Roosevelt, followed by Harry S.

Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower, countered and contained that impulse. The

specter of communism also did its part by alarming even the isolationists. The

establishment of the Soviet empire in eastern Europe and Soviet rhetoric about

the coming struggle against capitalism persuaded many Americans that they faced

a pressing danger that required continued engagement with allies in Europe and

Asia.

Today's world is not

wholly comparable to the worlds that emerged from the rubble of the two world

wars. Yet as the United States once again turns inward and tends only to its

immediate interests and smaller powers may abandon their hopes for a peaceful international

order and instead submit to the bullies in their neighborhoods, a hundred years

on, 1919 and the years that followed might still stand as a somber warning.

Today most historians

agree however that contrary to earlier legends it was the First World War

itself, not the treaty that concluded it, that set loose the forces and

ideologies that would convulse Europe and initiate another global conflict.

And that for all of Versailles' problems, it

represented a clear end to a major war in a way that we rarely see today.

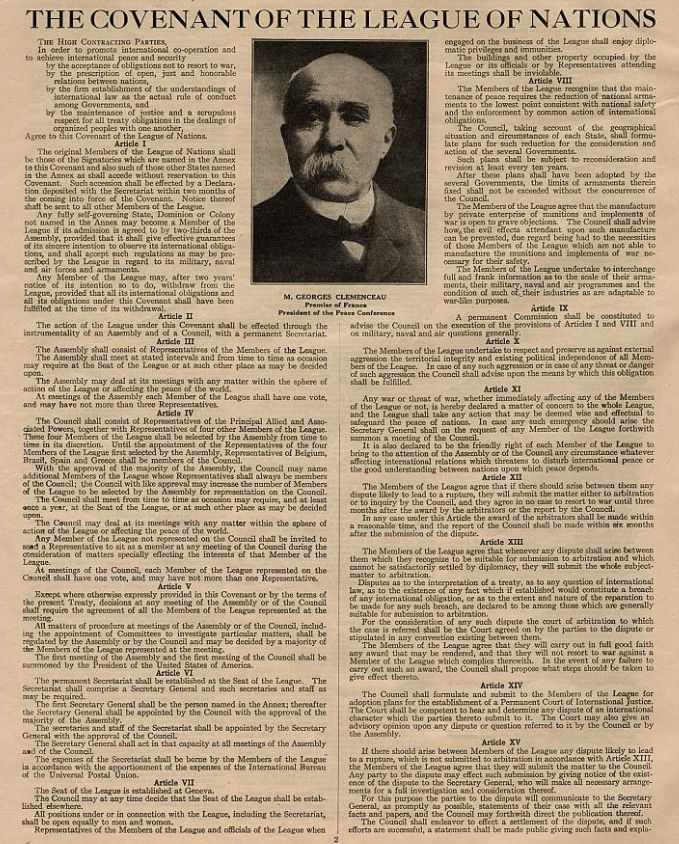

Also the League of

Nations was created as a result of the Paris Peace Conference on 10 January

1920, an international organization, headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, to

provide a forum for resolving international disputes:

The map underneath shows the 42 founding members of

the League of Nations (10 January 1920):

Other attempts to

make it more difficult to wage war where the draft Treaty of Mutual Assistance

(1923), which made aggressive war a crime; the abortive Geneva Protocol, which

narrowed the definition of lawful war; the resolution of the September 1927 League

of Nations Assembly declaring the use of war to settle disputes "an

international crime"; the Locarno Treaty of 1925 forbidding its

signatories from resorting to war; and a wave of bilateral treaties doing the

same.

Wilsons failure at

Paris, on the other hand, was rooted in the limited nature of his

internationalism, one focused entirely on diplomacy and politics, and

insufficiently attuned to the practical demands of the global economy.

Wereby

also the re-emergence of Britain’s traditional ambiguity concerning continental

affairs should not have surprised policymakers in Paris. The Clemenceau

government’s concept of a trans-Atlantic security system as proposed dring the Versailles deliberations was ahead of its time.

It would take another World War of even greater destructiveness to convince

both British and American policy elites of the importance of a strategic

commitment on the European continent. (2)

1. C.H. Hession, John

Maynard Keynes: A Personal Biography of the Man Who Revolutionized Capitalism

and the Way We Live, 1984, p. 306-7.

2. Peter Jackson,

Great Britain in French Policy Conceptions at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919,

Diplomacy & Statecraft, published on-line 28 June 2019, 30:2, p. 397.

For updates click homepage here