By Eric Vandenbroeck

Not unlike what I recently explained in the case of modern Ayurveda also modern yoga, as pointed out by such

expert historians like Suzanne Newcombe of the University of Cambridge, in

her 2004 A History of Modern Yoga, Karl Baier from the University of Vienna

and Faculty of History at the University of Cambridge and detailed in a

2010 breakthrough book by Mark Singleton, evolved in a discursive milieu that

incorporates such disparate strands as Hindu religion, occultism new thought,

and gymnastics.

Strands like this one

can among others seen reflected in the teacher of Paramahansa

Yogananda Sri Yukteswar an honorary member of

the Theosophical Society, whose Kaivalya Darsanam:

The Holy Science (1894) mentions Western astrology and fringe science

speculations about electricity and magnetism using the concepts of occult sciences and the astral body. Paramahansa Yogananda one of the most popular

purveyors of Yoga in the West continued these lines of thought.

Most recently pointed

out by Borayin Larios and Mark

Singleton, within the category of early scholar-practitioners of yoga, we must

include scholars affiliated with spiritual and religious organizations

producing translations and commentaries on yoga texts in the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries. "Probably the most significant of these organizations is the

Theosophical Society, founded by H. P. Blavatsky and Henry Olcott in 1875,

which published many early translations and commentaries on Patañjali’s Yogasūtras as

well as some of the earliest translations of haṭhayoga texts."

Theosophists stressed

the need for initiation and ‘traditional’ knowledge, meaning that esoteric

wisdom cannot simply be accessed and understood by a medium but requires a

learned preparation in esoteric teachings and the means to decipher them. India

came to be regarded as the treasure trove of ancient ‘Aryan’ wisdom that held that required key to

occultism. Behind that idea stood the orientalist discovery of the relationship

between Sanskrit and European languages, theories about the origins of religion

and ‘myths,’ and received an increasingly biological connotation towards the

end of the century. In this context, Yogic and meditational practices were at

the core of Theosophical interest in that supposed traditional ‘Aryan’ wisdom.

As a result, Theosophists gave yoga unprecedented global attention that formed

the basis for later developments in the twentieth century and New Age culture.

A major factor here

was the Theosophical concern for new editions and translations of Sanskrit and

vernacular texts: readers will find that Theosophical publishing houses printed

many contemporary editions and studies. In 1883, Rajendralal Mitra

wrote in the translation of The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali that no pandit in

Bengal had made yoga the special subject of his studies, demonstrating the

relative lack of interest of western-educated Indians in yoga. Mirroring

missionary and orientalist polemics, yoga was often regarded as superstitious,

barbaric, and dangerous. Not least, thanks to the Theosophists, this attitude

was beginning to change. One year before Mitra, the Indian Theosophist

Tukaram Tatya (1836–1898) had published James R. Ballantyne’s

translation of the first and second chapters of the Yogasūtra,

combined with Govindaram Sastri’s translation

of the third and fourth chapters that had been published in the journal Pandit.

This book, called The Yoga Philosophy, was thus the first English edition of

the whole of Patañjali’s text. Its

introduction was written by Olcott, who explicitly identified yoga with the occultist technique of self-mesmerization. A second enhanced version was published

in 1886, and a revised, more accessible version in 1889 by the leading

US-American Theosophist and co-founder William Quan Judge (1851–1896).

Thus in the course of

the past decades, also so-called kuṇḍalinī

yoga has pervaded popular culture and alternative religion. However, its

popular construction arose from a multi-layered process of re-interpretation,

originating in its initial exposure by non-Indian actors.

For example,

commonly, Sir John Woodroffe is credited with the dissemination of this Tantric

concept among devotees of European and American alternative religions. Yet,

Woodroffe had built upon earlier discussions on the part of the Theosophical

Society. Especially the (early) 1880s witnessed a vital discourse on Tantra and

some of its central components, such as kuṇḍalinī. In

an Orientalist manner, members of the Theosophical Society aimed to appropriate

Tantric concepts, in order to integrate them in their spiritual repertoire,

whereby the mysterious kuṇḍalinī energy was one among

many Tantric concepts that had aroused the Society’s interest. In the course of

time, kuṇḍalinī became a substantial content within

their religious program. As one of the earliest English references to kuṇḍalinī, the seminal text The Dream of Ravan constitutes

the starting point of that discourse and triggered ensuing Theosophical

concepts. Among the members of the Theosophical Society, the journal The

Theosophist was the foremost medium of communication, wherefore its

contributions provide valuable insights into that vivid discussion.

How Yoga came to the West

The Theosophical

occupation with yoga can be observed as early as the inception of the flagship

journal, The Theosophist, in an article about ‘Yoga Vidya’ from October

1879 until January 1880. Therein, yoga is discussed in the light of Mesmerism

and Spiritualism, with references to the Bhāgavata Purāṇa and the English translation of the Yogasūtra from Pandit. The year 1880 also marks the

first engagement with tantra, which set the stage for a Theosophical reception

of kuṇḍalinī, the chakras, and related yogic concepts that remain

influential up to the present day. In what follows, this first encounter with

tantra will be put in the context of the western esoteric reception of yoga and

meditation, focusing on selecting key concepts and the role of Indian authors in

their transmission into a western alternative religious culture.

Not only did the

Theosophical Society produce texts, but its reading rooms and distribution

houses provided a place for broad religious explorations; its speaking forums

allowed specific Indian individuals to more easily promote their own teachings

of yoga. And as De Michelis has argued in A History of Modern

Yoga, for example, Swami Vivekananda’s invitation for Americans and Europeans

to identify with Indian yoga was made in a Theosophically saturated milieu.

Theosophical

author Barada Kanta Majumdar drew parallels between

tantric-yogic practices, Mesmerism and Spiritualism. His remarkable

identification of ‘western’ and ‘Tantrik Occultism’ is among

others explained by Majumdar in his contribution to

Tukaram Tatya’s (1836–1898) influential Guide to Theosophy from 1887.

In ‘The Occult Sciences,’ Majumdar emphasized that western science was only

rediscovering what Indian Tantric wisdom had already been practicing throughout

the ages. While Theosophists and other esotericists had

long claimed the superiority of their synthesis of science, religion, and

philosophy over ‘materialistic’ mainstream science and scholarship, this

declaration of Indian spiritual-scientific superiority was a key characteristic

of the discourse about yoga, meditation, and tantra.

These assertions of

authenticity and superiority played directly into the inner-esoteric identity

struggles revolving around initiation into higher knowledge, and the

‘competent’ practice of magic. For this reason, the western esoteric reception

of Indian concepts was strongly contested, chaotic, and often

self-contradictory. What can be said with certainty is that western esotericism

and Indian traditions became deeply intertwined in the process.

Although a footnote

in the Theosophist from June 1883 was still cautious to distinguish between

‘black’ and ‘white’ tantra analogous to black and white magic, several

Theosophists were now willing to recognize the value of

‘Tantrik Occultism’ as the highest form of Indian esotericism.

In

1887, Srish Chandra Vasu (1861–1918) published The Esoteric Science

and Philosophy of the Tantras, a translation of the Śiva Saṃhitā. Vasu (also spelled Basu as is his

brother's name) was a Bengali civil servant and Sanskritist who

was closely involved in Theosophical circles. Notably, he

edited Sabhapati Swami’s work and appeared to have introduced the

notion of ‘Mesmerism’ into it. Vasu became a widely-read key actor for ‘Hindu

revivalism’ in the early twentieth century and promoted the values of Indian

culture based around the celebration of yogic texts, most notably the

Śiva Saṃhitā and the Gheraṇḍa Saṃhitā, from an

early point on. Apart from being hugely popular among esoteric actors, he was

also cited by established academics such as Friedrich Max Müller in his Six

Systems of Indian Philosophy (1899)1.

Early contradictions

In modern

translations and exegeses of “classical” hatha yoga texts, there was often a

marked hostility toward the very practitioners of the doctrines under

consideration. And not only Vasu but also exponents of 'practical' yoga in the

West, Swami Vivekananda and Mme. H. P. Blavatsky (who early on worked

with the Arya Samaj one

of the spiritual and intellectual progenitors of the RSS and its offshoot the BJP),

we're actually themselves pointedly antagonistic to Hatha yoga practices and

purposefully avoided association with them in their respective formulations

(even though such elements are not absent from their teachings).

However, Vasu’s

translations of hatha yoga texts were one of the very few accessible sources

for English speakers wishing to find out more on the topic. The only other

widely available printed English translations of Hatha yoga texts were Ayangar’s Hatha Yoga Pradlpika (Theosophical

Society 1893), Ayangar,

and Iyer’s Occult Physiology. Notes on Mata Yoga (Theosophical

Society 1893).

As some of the very

earliest and most widely distributed English translations of hatha yoga texts,

therefore, Vasu’s editions not only defined to a large extent the choice of

texts that would henceforth be included within the Hatha yoga “canon” but were

also instrumental in mediating Hatha yoga’s status both within modern anglophone

yoga as a whole and within the new, “free-thinking” modern Hinduism identified

by Vasu. For many decades, indeed, these works continued to be the source

texts for anyone interested in discovering more about hatha yoga, and they are

still republished and read today.2

What is being

attempted in Vasu’s Sacred Books translation is a redefinition of the yogin, in

which the grassroots practitioner of Hatha methods has no part. The modern

yogin must be scientific, where the Hatha yogin is not.

Vasu’s introduction

thus seems to flatly condemn the very practices of which his translation is a

document. If these practices, and those who undertake them, are morally

suspect, why bother representing them for an English-speaking audience at all?

Why not simply omit them, as Indologist Max Müller had done? What is

surprising is that Vasu’s original 1895 translation of his Gheranda Samhita opens with a dedication by the

“humble sevaka” Vasu to the well-known guru,

“whose practical illustrations and teachings convinced the translator of the

reality, utility, and the immense advantages of Hatha Yoga.” In this earlier

edition, therefore, Vasu presents himself as a “humble servant” (i.e., student

and devotee) of a renowned Hatha yogin, an insider rather than a mere impartial

critical commentator on hatha yoga. There is none of the doom-filled warnings

of the 1915 edition but rather a marked emphasis on the benefits of the

practices, as well as a long account of the miraculous, forty-day “burial” of

his guru under “scientific” supervision.

Vasu’s intention in

the 1915 volume is not simply to decry Hatha yogins but

to fashion an idea of what a real practitioner of yoga should be, an ideal

thoroughly informed by the scientific, rational, and “classical” values of the

day. Yoga implores Vasu, must be looked upon as legitimate science.

S. C. Vasu’s brother

and editor, Major Basu, was in fact one of the early, leading lights of

yoga that would come to full flower in India during the 1920s and 1930s with

Sri Yogendra (born Manibhai Desai,

1897–1989) and Swami Kuvalayananda(born

Jagannatha Ganesa Gune, 30 August 1883 – 18

April 1966). As a brief review of the early orientations of Vasu

and Basu shows, however, the dawn of Hatha yoga as promoted

by Shri Yogendra and Swami Kuvalayananda.

Arrived several decades earlier than has been supposed.

Basu associated the

chakras with the nerve plexuses, a product of both Theosophical and traditional

Indian concepts and an important step in the development of modern yoga

systems. Early Mesmeric theories had already emphasized the importance of the

ganglia for interactions between a subtle and a material body through ‘fine’

forces; this now became an integral point of reference for the explanation of

the yogic base of the brain; that is below the sixth chakra instead of at

the crown of the head. Basu associated the chakras with the nerve

plexuses, a product of both Theosophical and traditional Indian concepts and an

important step in the development of modern yoga systems. Early Mesmeric

theories had already emphasized the importance of the ganglia for interactions

between a subtle and a material body through ‘fine’ forces; this now became

an integral point of reference for explaining

yogic techniques. The association of the nervous system and the chakras is

often traced to Vasant G. Rele’s Mysterious Kundalini from 1927,

which appeared almost forty years after Basu’s article.

Another important

early moment in the reconciliation of tradition is A Treatise on the Yoga

Philosophy by Dr. N. C. Paul (also known as Navma Candra

Pala), originally published in 1850 but saved obscurity by the Theosophical

Society reprint of 1888. Perhaps even more than Basu’s work, this

study might be credited as the first attempt to marry Hatha yoga practice and

theory with modern medical science. Paul considers Hatha yogic suspension of

the breath and blood circulation in Western medical terms, once again (like

Vasu) evoking the internment of the guru Haridas as the paradigm of

yogic physiological control. As Blavatsky notes, the book’s appearance in 1850

“produced a sensation amongst the representatives of medicine in India, and a

lively polemic between the Anglo-Indian and native journalists”3.

Copies were even

burned because the text was "offensive to the science of physiology and

pathology4. However, its republication by the Theosophical Society, in the same

year as Basu’s seminal article in the Society’s journal, relaunched

it as a key text in the early formulation of hatha yoga as science, and it was

used as an authoritative source on hatha yoga by some European scholars.

The uniqueness of

India's theosophical movement rested on the fact that theosophy initiated its

own brand of modernity, thus creating a nexus between religion and politics in

a much more pronounced way than the other neo-Hindu organizations did. Professor

Gauri Vishwanathan tells us how the theosophists cite race theory to get Hindu converts. As shown earlier,

the ‘Aryan myth’ found great

popularity in 19th century Europe. German Idealism started viewing Indian upper

castes as Aryans: though much degenerated than their European counterparts due

to long intermarriages with Indian aborigines. Blavatsky and her followers saw

Aryans as the fifth root-race on earth and the highest in

contemporary times.

As seen above, the

foremost exponents of practicing yoga in the West, Swami Vivekananda and Mme.

H. P. Blavatsky, were actually themselves pointedly antagonistic to Hatha

practices and purposefully avoided association with them in their respective

formulations (even though such elements are not absent from their teachings).

Enter New Thought

Another crucial

role for modern yogic and meditational practices was played by a heterogenous

current called New Thought, which was largely stimulated by the writings of the

US-based Mesmeric healer Phineas

Quimby (1802–1866).

In this milieu,

Vivekananda was especially popular during his activities in the United States

since 1893.

Clearly influenced by

New Thought was Yogi Ramacharaka (alias William

Walker Atkinson (1862–1932), who wrote in a 1904 book subtitled The

Yogi Philosophy of Physical Well-Being, which was written by a Baltimore native

using the pen name Ramacharaka. “If we can but

grasp the faintest idea of what this means, we will open ourselves up to such

an influx of Life and vitality that our bodies will be practically made over

and will manifest perfectly.”

In the 1930s, several

South Asian yoga teachers in the United States presented the Yogi Ramacharaka exercises to US audiences as ancient

Indian yogic practices. The US-born Atkinson, who never traveled to India,

wound up influencing Indian understandings of yoga and beyond. Even if Ramacharaka’s teachings have little (if any)

historical continuity with Indian forms of yoga, his ideas and practices have

become central to the framing of many modern yoga traditions in cosmopolitan

contexts and Indian ones.

Enter present day Yoga

The first half of the

twentieth century was a dynamic period during which what was understood as yoga

– particularly yoga as a health-promoting activity – was rapidly changing. Soon

important figures in this reframing were Bishnu Charan Ghosh (

1903 – 1970), Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888–1989), who operated

a yogaśāla in Mysore (1933–1950) and

Chennai (Madras) from 1952.

The earliest

reference to a sun salutation in yogic texts appears

in Brahmananda’s nineteenth-century commentary on the Hatha Pradipika, which warns against “activities that cause

physical stress like excessive Surya namaskars or carrying heavy loads.”

Another way to translate this is “lifting weights,” which was also a popular

training method by the 1930s. It is often unclear what came from where, but

there are obvious overlaps between gymnastics and dynamic forms of yoga, such

as those taught in Mysore by Krishnamacharya.

Although, as seen

above, the physical methods of haṭha were

dismissed by Vivekananda (and the highly influential Theosophical Society)

as inferior to the ‘mental’ rājayoga, by the

1920s and 1930s, haṭha was beginning to

gain prominence in the hands of innovators like the above mentioned Swami Kuvalayananda, and Shri Yogendra published extensively

in English, including their respective journals Yoga and Yoga-Mīmāṃsā.

Swami Kuvalayananda founded his Kaivalyadhama ashram

in Lonavla (near Pune) in 1924. Shri

Yogendra's Yoga Institute in Santa Cruz (now a suburb of Mumbai) was a pioneer

in offering curative yoga therapy to middle-class patrons during the twentieth

century.

Yogendra had been a

keen athlete and wrestler in his youth and, shortly after establishing his

Institute, spent four years in the United States. It is possible that he gave

the first-ever demonstrations of asanas. Both Yogendra and Kuvalayananda focused primarily on yoga as a physical

practice. Both were also concerned with investigating modern scientific

justifications for yoga's perceived health benefits - they are often seen as

pioneers of the modern discipline of yoga therapy.

They also had an

interest in bringing yoga to a wider audience, which they did through several

popular publications aimed at the ‘person in the street.’ In the teachings of

Yogendra and Kuvalayananda, we perhaps first

encounter standing postures such as triangle pose (trikondsana)

or the warrior postures of contemporary yoga.

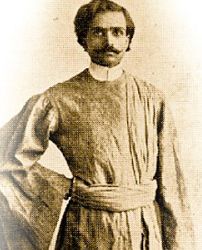

Autobiography of a Yogi

Bishnu Charan Ghosh was

a younger brother of the yogi Paramahansa Yogananda,

who became world-famous through his 1946 book Autobiography of a Yogi. This

whereby the teacher of Paramahansa Yogananda

(1893–1952) was Sri Yukteswar, an

honorary member of the Theosophical Society, whose Kaivalya Darsanam: The Holy Science (1894) mentions Western

astrology and fringe science speculations about electricity and magnetism using

the concepts of occult sciences and the astral body. Paramahansa Yogananda, one of the most popular Yoga purveyors in

the West, continued

these lines of thought.

Paramahansa Yogananda taught a mixture of both in the

United States in the 1920s, calling it Yogoda and

describing it as “muscle recharging through will power.” His “Energization

Exercises” promised well-being. “What is desirable in body culture is the

harmonious development of power over the muscles' voluntary actions and the

involuntary processes of heart, lungs, stomach, etc.,” says one of his

pamphlets. “This is what gives health.”

First Indian Yoga

teachers arrive in the USA and having its influence also on Europe A. K.

Mozumdar arrived in Seattle from Calcutta in 1903 and set out to teach what was

arguably the first form of “Christian Yoga” on the market. Mozumdar maintained

a small following in Spokane for about sixteen years, lecturing to the

community and working closely with the local branch of the Theosophical

Society, New Thought group, and Unity Church, as well as publishing a regular

periodical entitled Christian Yoga Monthly. After 1919, he relocated to Los

Angeles, from where he launched himself onto a broader lecture circuit along

the west coast and across the Midwest.

Mozumdar was also the

first individual of South Asian descent to be granted American citizenship in

1913, though it was later quite tragically revoked after the landmark case of

United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind. in 1913, which subsequently barred South

Asians from citizenship until the passage of the Luce-Celler Act in 1946.

However, though Thind would come to be remembered for this case, in which he

valiantly tried and failed to contest the arbitrary nature of racial

categorization, he also left a legacy as a spiritual author and teacher. Thind

was a Punjabi Sikh who came to the United States in 1913 to pursue higher

education, and he did indeed ultimately earn his doctorate from the University

of California at Berkeley. He was deeply influenced by the

Transcendentalists, especially Emerson,

Whitman, and Thoreau, and wove their universalist spirituality together with

Sikhism in his own teachings.

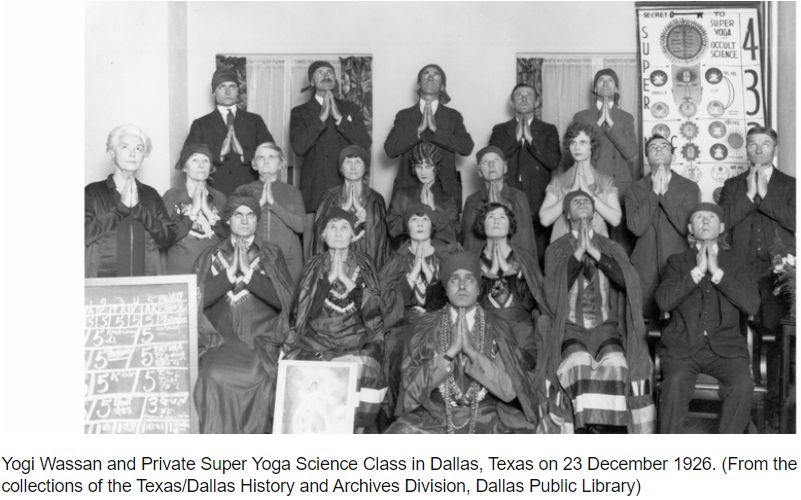

While some like

Mozumdar and Thind focused their teachings on devotional and philosophical

themes, others, such as Yogi Rishi Singh Gherwal,

Yogi Wassan Singh, Yogi Hari Rama, and then-Swami Yogananda taught a more

physically- oriented practice.Though Gherwal was the only one to prescribe exercises that would

today be recognizable as postrural yoga, Yogananda,

Hari Rama, and Yogi Wassan incorporated other forms of calisthenics with

distinctively yogic goals. Such Yogis often struggled to meet the needs of

audiences who were interchangeably looking for familiar images of ascetics,

magicians, mystics, and sometimes all three at once. They followed a

well-established lecture circuit, participated in vaudeville productions, and

published a number of philosophical and instructive volumes on yoga. Such

publications varied vastly in both quality and originality.

For instance, Yogi

Wassan s 1917 magnum opus, Secrets of the Himalaya Mountain Masters and Ladder

to Cosmic Consciousness, features a vaguely Hatha yogic model, relying upon a

system of plexuses opened along the principal energetic channels, which constitute

“The Secret Key of Opana Yama” or “the System used by

Householders to develop without excessive practice.” A combination of diet,

basic calisthenics, and specialized exercises promises to produce a “Super-Man”

and “Super-Woman” endowed with perfect bodily health and telepathy, as well as

the power of self-projection through an “ethereal body” The book is a rather

dense volume, containing a multitude of mantras in corrupted Sanskrit and of

indeterminate origin, lists of various stages of attainment, and instructions

concerning various practices, some of which appear rather ill-advised as they

require one to stare directly into the sun for lengthy periods of time. This is

followed by a set of recipes, some of which are for bathing the eyes,

unsurprising since most of the “Occult Concentration” exercises seem to involve

some form of optic manipulation, while others are for homemade candy. The end

lapses into practical miscellanea ranging from “How I make my Chicken Soup,” to

“What I Should Do if I Should Have a Hemorrhage or Diarrhea,” to “How I Shampoo

My Hair.”

As we have seen there

are two other early 20th-century Indian yoga pioneers, whose names are probably

better known in the West than either Yogendra or Kuvalayananda.

Swami Sivananda was born in 1887, and trained as a medical doctor, spending

time in Malaya. Although initiated into a renunciate monastic order in 1923,

Sivananda was throughout his life a modernizer, rejecting both some of the

inbuilt hierarchical structures of Indian society and the extremes of

renunciate life. In 1930, he founded the precursor of what in 1939 became the

Divine Life Society in Rishikesh, northern India, and from 1940 sent disciples

through India to teach a synthetic yoga that included asana, prandyama, mudra ai bandha practices alongside meditation,

devotional practices and service.

Postural yoga, in

turn, gained increasing importance when first developed in South Asia in the

1920s under the influence of gymnastics from Europe and the USA and other

systems of modern physical culture. Postural yoga focuses on postural

exercises, breathing- and relaxation techniques. In line with the rise of this

form of yoga the status of yoga within society dramatically changed. From the

late 1970s onward, yoga went mainstream and conquered the middle classes of

late modern societies. It ceased to be a countercultural or elitist occult

movement and was reinvented as a transnational pop-cultural phenomenon. Within

a short time, yoga became an essential part of the rapidly growing holistic

milieu that Christopher Partridge described as wellbeing

occulture.

Advocates such as

Yogendra and Kuvalayananda made yoga acceptable in

the 1920s, treating it as a medical subject. From the 1930s, the "father

of modern yoga" Krishnamacharya developed a vigorous postural yoga,

influenced by gymnastics, with transitions (vinyasas) that allowed one pose to

flow into the next.

Today Yoga

practitioners will return to their mats week after week for the same reasons

they have for the last fifty years; the experience makes them feel better,

although they might not be quite sure what exactly causes this effect.

Less wide-eyed than

the New Age forms of Yoga in the west is the militant form of

Yoga as promoted by President Modi's Bharatiya

Janata Party and

the RSS.

For more on the

subject of Yoga see our article: Yoga 2021.

1. Mark

Singleton, Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice, 2010,

pp.44–53.

2. On this, see

James Mallinson, The Gheranda Samhita.

New York: YogaVidya.com, 2004, and James Mallinson and Mark Singleton,

Roots of Yoga, 2017, 140–41.

3. Personal Memoirs

Of HP Blavatsky - Mary K Neff, 1937: 94-95.

4. Idem, 95

For updates click homepage here