In the fifth century BCE, Herodotus reports a story told of 'a group of wild young fellows' who traveled south from Libya into the African interior and, after crossing the desert and traveling far to the west, came to a 'vast tract of marshy country' inhabited by 'little men, of less than middle height', and to 'a town, all the inhabitants of which were of the same small stature, and all black. A great river with crocodiles in it flowed past the town from west to east'. The description may refer to the Niger river or to the Bodele Depression northeast of Lake Chad , now dry. Herodotus also reports Phoenician sailors circumnavigating the continent in a clockwise direction around the end of the seventh century or beginning of the sixth century BCE, and another voyage in the fifth century BCE down the west coast of Africa by Sataspes the Achaemenian, who reported to the Persian king Xerxes that, 'at' the most southerly point they had reached, they found the coast occupied by small men, wearing palm leaves'. (Herodotus, The Histories, London, 1996, p. 229).

Although Herodotus and his contemporaries usually named the whole continent ' Libya ', the name ' Africa ' is usually said to derive from the Greek word aphrike, meaning without cold. (J. Mark, The King of the World in the Land of the Pygmies (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), pp. 41-2. )

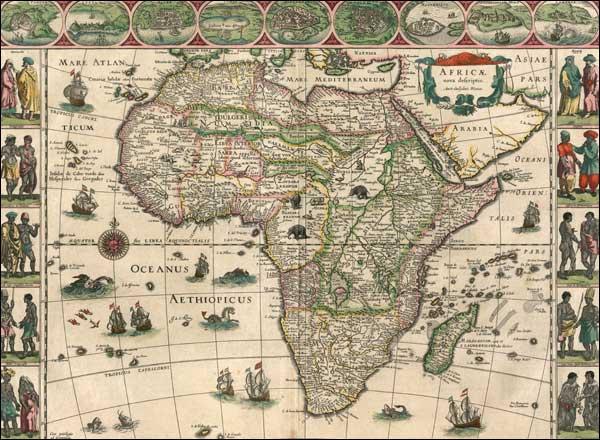

The Romans were familiar with the Mediterranean regions of North Africa , and with the trans-Saharan trade, which brought valuable goods from beyond the desert; but they knew little of the lands to the south. In the period after the decline of the Roman Empire, European knowledge of the continent remained limited, in part as a result of the Christian preoccupation with the Scriptures and with a world centred on Jerusalem and the Holy Land , and in part by force of political geography. Hostile Muslim rulers occupied the north of Africa and in any case European ships were incapable of travelling far to the south. Rumours filled the void. Sailors spoke of a Sea of Darkness , breathing with giant serpents. Other stories hinted of lands where gold, spices and precious stones might easily be found. One powerful tale was the twelfth-century legend of Prester John, a fabulously wealthy Christian ruler living on the east side of the Islamic empire. Stories of his empire were used to justify the Second and Third Crusades. Marco Polo even reported Prester John's death. (The Travels of Marco Polo,London: Wordsworth Classics, 1997).

Africa was not unknown to Europeans at this time, particularly the coastal regions of the Maghreb and of Egypt , but there was virtually no knowledge of the vast regions south of the Sahara . Beyond the familiar world of the Mediterranean coastal areas and the Near East , few ventured to go. Rumours abounded, however, and the trans-Saharan trade revealed to the European merchants established in the cities of North Africa the wealth (in gold and ivory) of 'black' Africa , far to the south. Books described the incredible wealth of lands beyond the seas, the extraordinary challenges that awaited explorers and the strange people and monsters lying in wait to attack them. The storytellers usually had little first-hand knowledge of these exotic regions. Typical were the descriptions given by Mandeville's Travels, fanciful accounts of travels in strange lands by an English squire who had never visited any of them. The legend of Prester John was also relocated to Africa . In 1415, a Portuguese invasion captured the Moroccan city of Ceuta . Following this conquest, and increased access to the transSaharan trade, stories began to circulate in Europe of kingdoms south of the Sahara, in Mali , Ghana and Songhai, and cities in Timbuktu , Gao and Cantor. Into the middle years of the fifteenth century, Dom Henrique, the Portuguese ruler of Ceuta , still determined to find Prester John's descendants. As late as the early fifteenth century, the Venetian fleet, probably the most powerful in Europe at the time, consisted of boats dependent on rowers and was effectively confined to the Mediterranean . New developments in shipbuilding by the Portuguese and Spaniards, however, made further exploration into the Atlantic possible. From the 1440’s onwards, the development of a loa-foot long ship, the caravel, enabled Portuguese sailors to travel greater distances. In 1482 Diogo Cio became the first European to visit the area of the modern Congo , when he reached the mouth of the Congo river and sailed a few miles upstream. It was the river that drew his interest. The Congo was the greatest river that any European had seen. For 20 leagues it emptied fresh water into the ocean. The waves breaking on the beach were an astonishing yellow colour, and the ocean was muddy-red as far as the eye could see. Cio recognized the importance of the Congo river as a possible source of transport and trade. He set up a stone pillar marking this Portuguese 'discovery'. He claimed the river and lands around it for the Portuguese king. (P. Forbath, The River Congo: The Discovery, Exploration and Exploitation of the World's Most Dramatic River, London : Seeker & Warburg, 1978, pp. 19,29, 32, 36, 38,40,48, 52,71-6, 81).

Cio regarded himself as the man who discovered these territories, yet the empire of the Bakongo already possessed a ruler, Nzinga Nkuwu, who led some 2-3 million people. The population of the capital Banza (later Sao Salvador) was around 40,000. Its citizens traded shells, sea-salt, fish, pottery, wicker, raffia, copper and lead. (J. Vansina, Equatorial Africa and Angola: Migrations and the Emergence of the First States', in D.T. Niane (ed.), General History of Africa, Volume IV: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century, Paris: UNESCO, 1984, pp. 551-77, 575). Nkuwu's authority was semi-feudal in character. Local lords had the right to control land, in return for which they paid taxes to their king. His people were skilled in iron- and copper-working and especially weaving. They grew bananas, yams, and fruit; they kept goats, pigs and cattle and fished. From palm trees, they manufactured oil, wine, vinegar and a form of bread. The society was prosperous and self-sufficient. Yet ·the Bakongo were said to lack any concept of seasons, or a calendar, and the wheel had not been discovered. Cao met Nzinga Nkuwu, and encouraged him to send ambassadors to meet the King of Portugal. Cao then continued on his travels, heading south. (E. Axelson, Congo to Cape: Early Portuguese Explorers, London: Faber, 1973, p. 95).

In the aftermath of Cao's visit, Nkuwu opened up his kingdom to Portuguese influences, and soon missionaries, soldiers and noblemen could be found at his court. Following further visits in 1491 and 1500, Nzinga Nkuwu even agreed to convert to Catholicism, starting Africa 's first Catholic dynasty. In 1506, Nzinga Mbemba Affonso succeeded him to the throne. Affonso was an intelligent, literate man, who understood that his country might gain from certain forms of European learning, their science, woodworking and om masonry, their weapons and their goods. The challenge was to allow selective modernization, to take the best parts of Western knowledge, while declining the worst parts, the cruelty and the greed. Over time, the actions of the Portuguese began to alarm the Bakongo. Their worries grew as the Portuguese extended and professionalized the slave trade. Prior to then, slaves had been part of the domestic economy, and were even sometimes exchanged, but the trade had never been central to the economy of the region. Under Portuguese rule, the number of slaves increased, and their economic role grew. As well as holding lands in today's Morocco , the Portuguese were also settled in today's Brazil , where they set Africans to work, digging and working mines, and harvesting coffee. Slaves were also sent to the plantations of the Caribbean. In order to work these lands at their full capacity, a regular supply of new labour was needed. In the land of the Bakongo, Portuguese traders began to promote feuds between neighbors, knowing that any conflict would result in greater numbers of slaves. Young men set out to work as masons, teachers or priests; but then, faced with the actual dynamics of the existing Portuguese economy, they soon realized that their fortune would be made more quickly if they learned to trade in slaves instead. Nzinga Affonso was a remarkable, learned man. His son was consecrated as a Roman Catholic bishop, the last black man to hold such a position for four centuries. Affonso became a great witness to the horror of sixteenth century Portuguese colonialism. Many of his letters survive, including one sent to King Joao III of Portugal in 1526:

Each day the traders are kidnapping our people ... children of this country, sons of our nobles and vassals, even people of our own family .... We need in this kingdom only priests and schoolteachers, and no merchandise, unless it is wine and flour for Mass .... It is our wish that this kingdom not be a place for the trade or transport of slaves. (A. Hochschild, King Leopold's Chost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Coloniced Africa, London: Pan Books, 1998, p.13).

The ruler of the Bakongo understood that many of the richest of his people were complicit in the slave trade. So taken were they by these new Western goods that they were willing to sell even their relatives. The only way to stop his people from doing this was to limit their access to the West. Of course, Affonso was no better than his times. He did not argue that all slavery should be abolished. He felt rather that it should be regulated, and conducted with respect to the society in which it took place. The Portuguese system horrified him because it was incapable of recognising any limit. In 1526, Affonso reported that the Portuguese were inciting his nobles to rise against the throne. By the mid-1530’s, 5,000 Bakongo slaves were being sent west each year. Some used the passage to rise up against the traders. (D. Richardson , Shipboard Revolts, African Authority, and the Atlantic Slave Trade', William and Mary Quarterly, 58, no. I ,2001).

In their absence, the society from which the slaves had been taken was reduced almost to penury. It was no longer able to defend itself from its rivals, descending from lands to the east.One particular group, the Yakas, or Gagas, or Jagas, attacked the Bakongo from the mid-1500’s onwards. Andrew Battell, a sailor originally from Leigh in Essex , observed these fierce warriors at close quarter. He came to Africa having been captured by the Portuguese. Battell described the Yakas as a bellicose people, harvesting palms for wine, pillaging and raiding, quite unlike the urbanised and more peaceful Bakongo. Battelilived among the Yakas for two years as a prisoner, before escaping, and later publishing his memoirs. He reported:

The Yakas spoile the Countrie. They stay no longer in a place, than it will afford them maintenance, And then in Harvest time they arise, and settle themselves in the fruitfullest place they can nnd; and doe reape their Enemies Corne, and take their Cattell. For they will not sowe, nor plant, nor bring up any Cattell, more then they take by Warres. (The strange adventures of Andrew Battell of Leigh in Essex, sent by the Portugals prisoner to Angola who lived there, and in the adjoyning Regions, neere eighteene years', in S. Purchas, Hakuytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrimes: Contfirming a History of the World in Sea Voyages and Lande Traivells by Englishmen and others; Volume VI, Glasgow: James MacLehose & Sons: 1905, pp. 367-430, 384).

In 1571, the Bakongo, perhaps by virtue of their more productive economic base and better-organised state system, or possibly as a result of access via the Portuguese traders to muskets and gunpowder, finally defeated the Yakas. In the years that followed, a number of attempts were made to rebuild their society and to establish a new relationship with the West, based on fairer relations of trade. Western rugs, beads, mirrors, knives, swords, muskets, gunpowder, copper, tin and alcohol have all been found in the ruins of the towns.10 Yet the series of wars between the Bakongo and their neighbours served to undermine the older, more urban civilisation of the Bakongo. Soon the Bakongo were neither secure nor free. (R. W. Harris, River of Wealth , River of Sorrow: The Central Zaire Basin in the Era of the Slave and Ivory Trade 1500-1891,New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981, p. 44).

One legacy of the Portuguese conquests was a diminution of the power of the Bakongo kings in relation to other regional rulers, who had previously recognised their sovereignty. The seventeenth century saw many wars between the different peoples of the region. Lisbon made a series of attempts to re-establish a base at the capital Sao Salvador, which failed. The city itself was destroyed in 1678. Another Capuchin mission was expelled in 1717. In 1857 the German traveller Dr. Bastian found Sao Salvador 'an ordinary native town', with few monuments of its past. (K.Thornton, The Kingdom of Kongo : Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718, University of Wisconsin Press, 1983, p. 84).

NFew societies flourished on the ruins of the Kongo and Yaka societies. The kingdom of Kuba was founded in the sixteenth century by a federation of immigrants, the Bushong. They settled in the area along the Kasai and San kuru rivers. Beside the Bushong groups, the Kuba federation incorporated among its members the previous inhabitants of the region, the Twa and the Kete, who continued to live alongside the new arrivals. The Kuba monarch was elected for a limited, four-year term. Women were eligible to stand for office. The kingdom lasted till 1910. (T. Mukenge, Culture and Customs of the Congo, Westport CT: Greenwood Press, 2002, p. 13).

Further south, there were several large civilisations, based in present-day Katanga . A Luba state was formed by clan fusion perhaps before 1500, a Lunda state before 1450. The Luba had four kingdoms by the seventeenth century: Kikonja, Kaniok, Kalundwe and Kasongo. The Lunda state arose to Luba's south-west, covering about 400 by 800 miles with two tributary states by 1760, Yaka and Kazembe, each with a capital so named. A Bemba empire began to form towards the end of the eighteenth century under Lunda pressure. These civilisations traded with the Portuguese but were not conquered. The Luba empire broke into Yeke and Swahili-Arab spheres in the 1870S and 1880s, while Yeke and Chokwe broke up the Kazembe and Lunda states. (D. Birmingham , Central Africa from Cameroon to the Zambezi, in R. Gray (ed.), The Cambridge History of Africa , Volume IV: From 1600 to '790,Cambridge University Press, 1975, pp. 325-83).

Despite the destruction of their main allies and their own defeat, the Portuguese retained an interest in the region. In the late eighteenth century, Lisbon-backed African and mulatto traders (pombeiros) traded with the kingdom of the Kazembe to the south. In the middle of the nineteenth century, Arab, Swahili and Nyamwezi traders from present-day Tanzania also penetrated the highlands of the Congo from the east, and began a trade there in slaves and ivory. A lively Arabic literature began, describing travels through northern and central Africa. (See Travels of an Arab Merchant in Soudan, London: Chapman & Hall, 1854). Some traders established their own states. One merchant, Muhammad bin Hamad, or Tippu Tip, from Zanzibar ruled much of eastern Congo, into the 1890’s. (H. Brode, Tippu Tip: The Story of His Career in Zanzibar and Central Africa, Zanzibar: Gallery, 2000).