The Sepoy Mutiny and British India

By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Prescribed reading

for those training for imperial service in 1871, was W W.

Hunter's, The Indian Musulmans: Are They Bound in

Conscience to Ache Against the Queen? In the early nineteenth century, Hunter

describes there was a large rebel camp that attracted both Afghan and Indian

fighters to a jihad initially against the Sikh power centred

in the Punjab, and then against their British successors. Rather than being a

traditional movement untouched by the West, this 19th century jihad was modern

and indeed cosmopolitan in character, a fact to which Hunter's descriptions of

its leader's rapturous reception in the British cities of Calcutta and Bombay

attest. Similar are his descriptions of the vast and secret network of foreign

supporters, financiers and recruits to this Afghan jihad. In short it bears an

uncanny resemblance to the 1980’s Afghan war. Both cases witnessed the

establishment of a charismatic foreign leader and his compatriots in

Afghanistan.

During the 1850’s

then, Wilayat Ali, a Wahhabbi and student of Syed

Ahmad of the Delhi Sultanate, confecting the story that Syed Ahmad was not really dead but merely waiting in the mountains to resume

the jihad, thus shaping Wahhabism into a cult centered on its hidden imam. A

secret network based on Patna was established by which funds, supplies, and

weapons were sent along a covert caravan trail to the Mahabun

Mountain, along with volunteers to be trained as mujahidin. In January 1853, in

response to an appeal from a local chief, the British launched a raid on the

Hindustani camp at Sittana, and the raid forced the

Hindustanis to put off their jihad, which was rescheduled for the summer of

1857, Sepoy Mutiny.

Not shown in “The

Rising” many young Wahhabis, easily identified by their distinctive black

waistcoats and dark blue robes, fought and died in the uprising. In the end

several hundred mutinous soldiers fled to the camp where Wilayat Ali had died

of a fever a year earlier so it was his younger brother, Inayat Ali, who

launched a final a raid into the plains, apparently believing that he would be

joined by mujahidin sent up from Patna.

In April 1858 the

British military commander in Peshawar led a three-pronged assault on the Mahabun Mountain to wipe out the Hindustani Fanatics once

and for all. Inayat Ali had just died of fever, and the Wahhabis were again

taken by surprise. The mujahidin were surrounded and all but wiped out, yet

somehow Wilayat Ali's eldest son, Abdullah Ali, escaped to fight another day.

The survivors moved to an abandoned settlement named Malka, where they were

entirely dependent on the charity of their neighbors. Amazingly, the Wahhabis

bounced back, again. They rebuilt their organization

and reopened their underground trail to the North-West Frontier.

Under the leadership

of Abdallah Ali, they moved from one hideout to another, harassed in turn by

the local tribes and the British authorities. In 1873, Abdullah Ali's youngest

brother in Patna appealed for an official pardon,

rejected on the grounds that the Hindustani Fanatics would eventually be forced

to give up. But the government was, as often before, indulging in wishful

thinking. The Hindustanis clung on, kept alive by handouts from the Pathan

tribes.

When a British

journalist came to write about the North-West Frontier in 1890, he noted that

the Hindustanis were widely admired among the tribes for their "fierce

fanaticism." Their colony was celebrated locally as the Kila Mujahidin, or

"the Fortress of the Holy Warriors," wherein they "devoted their

time to drill, giving the words of command in Arabic, firing salutes with

cannon made of leather, and blustering about the destruction of the infidel

power of the British." It was said that they were still awaiting the

return of Syed Ahmad, their Hidden Imam. Then came the great frontier uprising

of 1897–98, beginning in Swat and spreading like the proverbial wildfire south

through tribal country, and requiring an army of 40,000 to reduce them to

submission.

The nature of the

society of the first Muslims, the forefathers or salaf,

and the incredible expansion of the Islamic community throughout the Arabian peninsular and beyond towards the Maghreb and south and

central Asia during the time of the Prophet and his immediate successors has

been proof to devout Muslims ever since that following the instructions of

Allah and the examples of the Prophet will ensure a just and peaceable society

and the concomitant cultural, military and political superiority of the Islamic

world. The texts and the example of the first generations of believers thus

provide an ideal, a reference point, that can be compared, inevitably

unfavorably, with any given extant government, situation or ruler. They offer a

vision of an' authentic' and 'true' Islamic society, against which reality

rarely stands much comparison. This is a political resource of enormous power.

The core texts of the Qur'an and the hadith are thus 'closed', in that they are

unchangeable, but also ,open', in that they are

infinitely flexible, providing answers in principle to all

questions of behavior at all times. The former quality means they have

an autonomy that prevents manipulation by anyone hoping for short-term gain in

a specific local or political context, the latter means they can be made

appropriate for all people in all situations.' This again means that Islam is

always politically engaged as it allows dissident movements in the Islamic

world to appeal to the 'purity' of an, often imagined, earlier society or religio-political order, predicated on a 'true', authentic

reading of the Holy texts. There is thus an obvious religious answer, and

proscribed programme for action, for any political

grievance. If the corrupting elements are purged, the logic runs, a fair and

just and happy society will be established.

While recommending

the inclusion of Muslims into European society upon more or

less equal terms as a way of treating with their militancy, Sayyid Ahmad

Khan stressed the fact that the gentlemen who deserved such inclusion were to

be men like himself, anglicized Muslims who could interpret Islamic passions to

the West and European reason to the East. Despite their often

sophisticated meditations upon the nature and future of modern Islam,

men like Sir Say vid were forced by political circumstances to play the role

merely of intermediaries between Christians and Muslims because none was able

to assume political power in his own name. In order to

do this Savvid Ahmad Khan, like his liberal

descendants today, who continue to play the same role, also had to emphasize

the threatening aspects of an Islamic violence whose substance he was (like

today’s moderate Muslims) ostensibly denying.

In many ways today's

jihad builds upon the earlier ventures described here. It, too, is located on

the peripheries of the Muslim world geographically, politically and

religiously, operating now in places like Chechnya, Afghanistan, Pakistan and

India, as well as in Thailand and the Philippines. See Case Study.

But the key to

Afghanistan as such are the Pashtuns, historically referred to as the Pathans.

During British intrigues in the nineteenth century, the Pashtuns were

romanticized by the likes of Rudyard Kipling as the primitive and fiercely

volatile tribes occupying the northwest frontier region of India. In the

nineteenth and twentieth centuries, weak Afghan governments used the

independent Pashtun tribes as a buffer against British forces moving north to

thwart Russian influence. This was the Great Game. In 1893, the British

threatened to cut off arms shipments that the Amir of Afghanistan desperately

needed, forcing him to sign a treaty creating the Durand Line, effectively

splitting the Pashtun region in two. Individual villages, and even families,

suddenly found themselves on opposite sides of supposed international borders.

The situation was only exacerbated in 1907 when Britain and Russia ratified the

Anglo Russian Convention, designating spheres of influence in Central Asia. By

this juncture, the Pashtun as a people were forever lost to the British as

possible allies or even neutrals.

As a result, over the

course of time, the British Government of India vacillated between policies of

purposeful withdrawal, in which troops were stationed on the more easily

secured plains east and south of the Pashtun tribal areas, and policies of

aggression, in which expeditions were mounted into Pashtun territory for

extended engagements with the various tribes. In 1901, the British opted to

contain the Pashtun tribes by re-designating the area they inhabited as the

"North-West Frontier Province." This area was separated from the

remainder of the Punjab, divided into districts under British political agents

who reported directly to the central government, and were administered via

pseudo-treaties with occasional military reprisals to keep them in line. We

already discussed British micromanagement in Iraq's tribal areas. This policy

was no less disastrous in Afghanistan as it in case of Iraq's tribal areas

described in the previous part.

While Afghanistan

gained its independence from Great Britain in 1919, the U.S. did not confer

recognition until 1935, and no diplomatic mission was opened until 1942. Thus one can say that American relations with Afghanistan

were rocky from the start.

Much of the initial

delay resulted from the U.S. government mirroring British diplomatic moves. At

the time of Afghanistan's independence, the British had not yet concluded their

final treaty from the Third Anglo-Afghan War. When the U.S. did establish relations

with Afghanistan over two decades later, and had to do

with trumping the Nazi German efforts to gain a foothold in the region.

U.S. relations with

Afghanistan regained strategic priority when the Soviet Union invaded the

country in December of 1979. Throughout the 1980s, Saudi Arabian-funded and

American trained and equipped mujahidin battled the Red Army, forcing the

Soviets out of Afghanistan in 1989. With the Russians out, these same jihadists

we empowered against the Communist threat changed their objectives in order to obtain new sources of funding and maintain their

jobs as holy warriors.

The leaders of so me of these groups say that they originally joined the

mujahidin for religious reasons. Their intent was to transform themselves and

simplify their lives. Several of these former idealists now admit they remain

in the Islamist fighter trade for the salaries. These men have skills and

careers like anyone else. As for the Afghans as a whole, a few years of

occupation are tolerable. If the coalition forces fail to bring stability soon

however, they may find themselves facing an unexpected foe in the common

Afghan, even a decade from now or more. If the coalition forces

we fail to eradicate the Pashtun led Taliban, simply through their tenacity,

these groups may eventually succeed in convincing the the

majority Pashtun population, that they can outlast the U.S. and provide the

long-term security that the Afghan people are seeking.

Al Qaeda-linked

groups, various well known Afghan warlords, and strongly fundamentalist Islamic

social organizations are operating in eastern Afghanistan and the Northwest

Territories of Pakistan. Their low intensity insurgent movement is made

possible because of the Pashtun social code named Pushtunwali.

This code states that any person, even an enemy, who asks for protection and

hospitality, will receive it.

After being given

sanctuary, these groups provide their hosts with money and expertise in areas

such as medicine. Should the coalition forces not act decisively against the

leadership of these groups, the native insurgents, much like Hezbollah

guerrillas in southern Lebanon, and Hammas in Palestine, may eventually become

integrated into the social fabric of Pashtun life.

Within a generation,

we may very well end up with a region as strongly fundamentalist as the US

faced at the beginning of Operation Enduring Freedom, and a population as

openly hostile as the one the British faced in the nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries.

The first armed

involvement by the British was initiated to protect the northern approaches to

the British Raj (India) from Russian expansion. The original intent was merely

to replace Afghan ruler Dost Mohammad, with someone more sympathetic to British

interests. The British answer to replacing Dost Mohammad was to allow Shah Shujah al-Malik to take over as ruler of the country. He

was a despised former ruler of Afghanistan who the British intended to place on

the throne using their military assistance along with that of Ranjit Singh, the

Sikh Maharajah of the Punjab. Singh ruled the Punjab from Lahore, southeast of

Kabul across the Indus River. (Olaf Caroe, The Pathans 550 B.C.-A.D. 1957, 1958

,317-20.)

Why the British

thought it a wise decision to allow a despised former ruler, different in

religion, culture and ethnicity from the vast majority of

Afghans, to try to hold the throne in Kabul with the aid of a rival Sikh power,

is a mystery. But the British arrived in Kandahar in April of 1839 without a

fight. Within weeks of their entry into the city, the' Afghan's true feelings

toward the British began to manifest. The Chiefs were hoping that the Shah's

British military backing would soon leave the country, allowing them to regain

full control of their territories.

After a two-month

delay, the army advanced north from Kandahar to the fortress of Ghazni, ninety miles south of Kabul. The hastily formed

Intelligence Department, consisting of two British Political Officers, informed

Lt. General Sir John Keane, commander of the expedition, that Ghazni would be undefended when the British arrived. Based

on this faulty intelligence, Keane foolishly decided to leave the siege guns at

Kandahar. After a four-week march, in July of 1839, the British army arrived at

Ghazni and found the fortress to be heavily defended.

(Brigader General Sir Percy Sykes, A History of

Afghanistan, 1940,7-8.)

Fortunately for the

British, a traitor nephew of Dost Mohammad came into the British camp and

informed them that the Kabul gate, a side gate into the fortress, was not

heavily guarded.

Pounding the gate

with 900 pounds of gunpowder, British infantry and footsoldiers

poured into the breach. Over one thousand Afghans were killed while only

seventeen British soldiers lost their lives.

Before the British

Army even began to regroup and march on, Dost Muhammad sent his brother to the

British camp, proposing a deal in which the Dost would become Shah Shujah's prime minister. William H. Macnaghten,

the blustering commander of the British expedition, coldly refused

the offer. Considering that Dost Mohammed had never actually carried out any

action that directly opposed British intentions in the region, one cannot

wonder if this compromise may not have worked, at least long enough to set more

strategic goals in motion. As it was, the deal was declined, and British

indecisiveness during their subsequent occupation of Kabul would reinvigorate

the Afghan will, and seal the fate of thousands of

British subjects. (Sykes, 11.)

The first major

British mistake came when Dost Mohammad, along with his entire clan, fled north

into Uzbek tribal territory, in modern day Uzbekistan. The small British column

sent in pursuit of the Dost inadvertently used one of his supporters as a guide

and were unable to catch up to the fleeing royal, allowing him to escape. Thus,

although the British made a triumphant entry into Kabul, they left intact the

entire enemy force from the Amir down to the lowliest enemy soldier who used

the situation to blend in to the population.

Foreshadowing the

disaster to come, when Shah Shujah rode into Kabul in

August of 1839 and reoccupied his palace, he was welcomed with empty streets

and indifference on the face of the city's inhabitants.

There is no question

that today in Afghanistan, President Karzai would lose control of the

government, and likely his life, if not for the presence of American and

international troops in Kabul. At present, the nation is in the infantile

stages of building an adequate army and police force capable of resisting the

aspirations of various powerful warlords. Karzai's power does not extend

outside of Kabul and the satellite citadels such as Kandahar. When it comes

right down to it, the combined use of arms and money, sometimes referred to as

the carrot and stick method, is really the only true means of

succeeding in international affairs. Human beings, whether as individuals, or

as a collective group who form an empire, act each

moment to improve their lot in life. Anything that one or the

many agree on, they do so because it somehow serves their own interests.

The only way to force a change is if by doing so, it benefits them in some way,

or if the alternative to not accepting the proposed situation somehow makes

life worse. On a smaller scale, the combined lack of carrot and stick is one of

the problems the British faced in Afghanistan, and one from which the coalition

forces today can learn an interesting lesson.

Shortly after the

British invasion of Afghanistan, Yar Mohammad, master of Herat, put aside his

differences with the Persians for their siege two years prior and began

scheming with them against the British presence in Afghanistan. Learning of Yar

Mohammad's conspiratorial engagement with the Persians, the British chose to

bribe him into cooperation. Yar Mohammad took the money and continued to plot

against the British. Two years and 200,000 British pounds later, the British

realized the folly of their policy and ended the payments. By this time, the

British did not have the military assets to send against Yar Mohammad in order to break his will by force. In the end the British

political mission was forced to leave Herat, and the British buffer against

both Persian influence to the west, and Russian

influence on the northern flank of Afghanistan, was lost.

Beyond Herat, the

situation was not much improved. The method by which the British chose to

control the country was not a good fit for the demographics and socio-economic

conditions of the time. Shah Shujah was the supposed

ruler of the country, but was held in place through

the force of the British military. British officers led both the Shah's troops

and the local tribal levies, and they were paid out of British coffers. The

Afghans especially chafed at the heavy taxes imposed on them to maintain these

troops, and the fact that the British could launch expeditions against them

without any input from the Shah or local chiefs. This method of operation has

been improved on in contemporary Iraq where the United States is footing the majority of the bill for both U.S. and Iraqi troops and

the Iraqi government has the final say in nearly all military operations.

Macnaghten wrote to his superiors in India and England that the

situation in Kabul, and the country in general, was tentative. Over the course

of the first year in Afghanistan, he recommended that additional troops be sent, and requested that he be allowed to advance on Herat

in the northwest, and Peshawar in the east. In the second major mistake of the

occupation, no units of significant size were sent. Aside from small garrisons

located along the lines of communication to India, and small probing forces, his

requests to expand the British area of control were denied. (Sykes, 16-8.)

From a historical

perspective, while the suggested campaigns would have likely overstretched

British assets, the potential success of taking the fight to the enemy were

instead replaced with the folly of doing nothing. In eerie foreshadowing of

what was to come, the road from Kabul down through Ghazni

to Kandahar was passable only by permission of the western Ghilzai,

while the eastern Ghilzai held the route from the

capital to Jalalabad in the hollow of their hand. Meanwhile, in some of the few

encounters between the British and the local populace outside of Kabul, the

British were not endearing themselves to the Afghan people. On one occasion, a

detachment sent to garrison Bamian, located just

outside of Kabul, demanded that the local Hazara inhabitants sell the army food

and supplies. When the people refused because the food was needed to feed their

cattle in the upcoming winter, the British attacked the local fort. The supplies

in question were burned and the fort's occupants were shot. (Sykes, 15.)

Throughout the

region, Afghans of various ethnicities grew increasingly angry at the

efficiency of the British backed taxation system, the inefficiency of Shah Shujah's government, and were increasingly swayed with Dost

Mohammad's claim to be "Commander of the Faithful." Support for the

Dost amongst tribes situated in every cardinal direction from Kabul began to

grow. Surprisingly, the Dost defeated a small British force just north of

Kabul, then rode to the capital and surrendered to Maenaghten.

The lack of British ruthlessness at this juncture led to the third major

British mistake of the campaign.

Dost Mohammad's

surrender as a victor enhanced his position in the eyes of the British, who

merely exiled him to Ludhiana in the Punjab. This comfortable exile served to

maintain the dignity of the Dost's clan in the eyes of his fellow Afghans. To

compound their mistake, the British did not pursue Dost Mohammad's son, Akbar

Khan. As the months passed, the wives and children of British and Indian Sepoy

soldiers began arriving in Kabul. Seeing this as another sign of a prolonged

occupation, Akbar Khan picked up where his father left off, gaining followers

and biding his time to destroy the British.

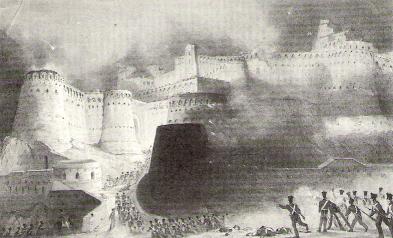

The fourth and most

disastrous mistake for the British was the most avoidable and sealed the doomed

fate of the British in Afghanistan. After the initial entry into Kabul, the

British had to decide where to garrison the army. The most reasonable location

would have been in the Balla Hissar, the great fortress that dominated the city

of Kabul, an astute and impressive fortification even to this day. Captain Alexander Burnes, strongly recommended the fortress,

and the British initially set out to fortify the structure. When Shah Shujah complained that the Balla Hissar dominated both the

city and, more importantly, his palace, and lowered his dignity among the

Afghans, Maenaghten agreed to abandon the fortress as

British quarters. Instead of occupying this nearly impregnable structure, the

British eventually built a cantonment on a low, swampy plain outside of Kabul.

The isolated cantonment kept the British out of touch with the pulse of the

Afghan people. Tactically, the cantonment was much too large to be adequately

defended. It was dominated by the Beymaroo Heights,

hills northwest of the cantonment, and various forts, none of which the British

occupied. Finally, the cantonment's supply compound

was located a quarter mile away, a decision that was soon to prove utterly

disastrous.

Runjeet Singh, the faithful Sikh ally to the British, died in

late 1839, and Sikh warriors now feIt no apprehension

at hassling British officers passing through Sikh territory on their way to

Kabul. This left Avitabile, an ltalian

who ruthlessly governed Peshawar to the east of Kabul, as the only barrier to

the Sikhs and Afghans joining together to close off the Khyber Pass to the

British.

When in the south,

Baluchi tribes laid siege to Khelat, a city in modern

day Pakistan south of Quetta. The city quickly surrendered and the British

political officer, Lieutenant Loveday, was taken captive. He was horribly

treated while in captivity and his throat was cut just as a British punitive

force approached the rebel camp several months later.

As these other events

were unfolding, in the harsh wastelands between Kabul and Khelat,

the Durrani tribes of Kandahar began to rise up in

opposition to Shah Shujah's ruIe.

In their resistance we see the glaring failure of the British to immerse

themselves in the local political and cultural situation. The Durrani, founders

of the earlier Afghan Empire, and ancestors of Afghanistan's current president

Karzai, had been heavily oppressed under Dost Mohammad's rule. They originally

rejoiced at Shah Shujah's reclaiming of the throne,

but his lack of follow through with their requests, combined with the

patronizing attitude of the British, led the Durrani to take up arms against

the Shah and his British protectors.

* Shortly after one

of his men killed (September 1853) Colonel Frederick Mackeson the most senior

British official on the North-West Frontier of the Punjab, leader of the

Wahhabi- Hindustanis Inayat Ali issued following statement: British rule in

northern India had officially begun in 1765, would end in June 1857. (C.Allen, God’s Terrorists, 2006,

p.116)

Allan describes how

letters and other papers seized during the suppression of what the British

termed the Sepoy or Indian Mutiny of 1857 show that there was no overarching

conspiracy to free India from a foreign yoke. The central thesis of his new

book however is that ,”the Wahhabis, who alone had a

well-thought-out plan to overthrow the British” (Allen, 2006, p.125)

According to Allen’s

well researched book, shortly after the Mutiny broke out a fatwa was issued in

Delhi, declaring a jihad against the British ”a group

of mullahs erected a green banner on the roof of the city's greatest mosque,

the Jama Masjid, and published a fatwa proclaiming jihad.” (p.136.) By the end

of September 1857 Delhi was a ghost town, entirely cleansed of Muslims, who

were now viewed by the ritish as the real enemy.

(Allen, p.162)

Jihad in

the British Empire and Now.

For updates click homepage here