By Eric Vandenbroeck

9 Oct. 2019

US. and Kurdish

officials said late Tuesday that they expect Turkey to launch a major offensive

into northeast Syria within the next 24 hours, after U.S. President Donald

Trump appeared to give Ankara the green light to begin the operation.

Whereby early in the

morning today reports have come in that Turkish troops have begun crossing

Into Syria.

The Syrian Democratic

Forces (SDF) who operate in the area are US allies. They are led by the Kurdish

People's Protection Units (YPG), which Turkey considers a terrorist

organization. Trump's decision to pull troops from the area cleared the way for

Turkey to attack.

The scale and size of

a potential Turkish operation remain unclear. Officially Turkey wants to create

a 32-kilometer-deep, 480-kilometer-long corridor (20 miles deep, 300 miles

long) inside Syria along the border to protect its security.

A Turkish military incursion into northeast Syria would likely send hundreds of thousands of civilians

fleeing into SDF-controlled areas further south and into neighboring Iraqi

Kurdistan.

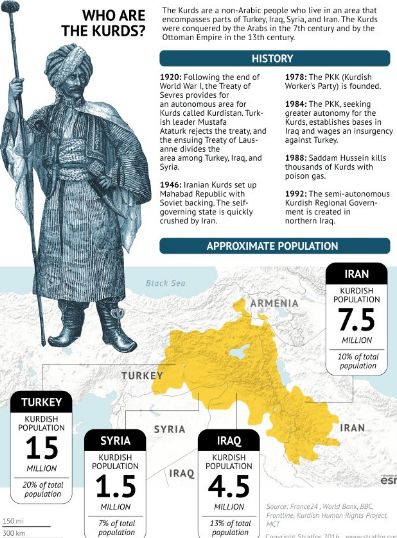

Who are the Kurds?

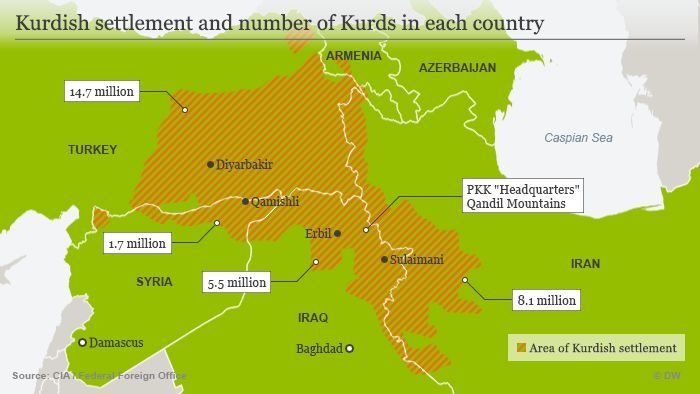

A subject I have covered in a different context before, the Kurds live under the rule of several states that

succeeded the Ottoman Empire: the Republic of Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. Kurds

also lived in large numbers in Persia or Iran, and there were smaller Kurdish

populations in Russia and Lebanon. Their population statistics were disputed

because of the states where Kurds lived tended to minimize their numbers, but

Kurds made up some 20 percent of the population of Turkey, more than 20 percent

of the population of Iraq, and close to 10 percent of the population of Iran.

With a total population of some 24 million to 27 million by the late twentieth

century, Kurds made up the largest ethnic group without a state in Europe or

Western Asia.

Kurdish identity,

society, and politics have been heavily influenced by the state-building

projects of the countries within which they live. As a result, while many

Kurdish nationalists may dream of a greater independent Kurdistan, Kurdish

political parties’ demands for greater rights and autonomy have traditionally

been directed towards the states within which they live, even as Kurdish

movements in one part impact those in another part.

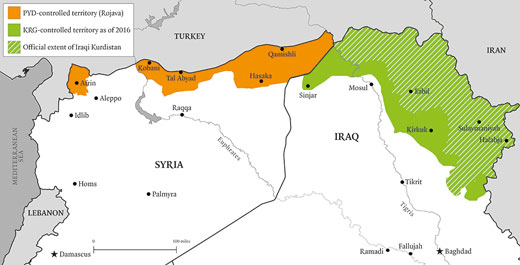

Rojava, as the Syrian

Kurds call the area they gained control of when the Syrian army largely

withdrew in 2012, and which now stretches across northern Syria between the

Tigris and Euphrates. Whereby in Iraq, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG),

already highly autonomous, took advantage of ISIS’s destruction of Baghdad’s

authority in northern Iraq to expand its territory, taking over areas long

disputed between itself and Baghdad, including the Kirkuk oilfields and some

mixed Kurdish-Arab districts.

Turkey has been

appalled to find that the Syrian uprising, which it hoped would usher in an era

of Turkish influence spreading across the Middle East, has instead produced a

Kurdish state that controls half of the Syrian side of Turkey’s 550-mile

southern border. Worse, the ruling party in Rojava is the Democratic Union

Party (PYD), which in all but name is the Syrian branch of the Kurdistan

Workers’ Party (PKK), against which Ankara has been fighting a guerrilla war

since 1984. In the year since ISIS was finally defeated in the siege of the

Syrian Kurdish city of Kobani, Rojava has expanded territorially in every

direction as its leaders repeatedly ignore Turkish threats of military action

against them.

For the Kurds in Rojava

and KRG territory this is a testing moment: if the war ends their newly won

power could quickly slip away. They are, after all, only small states, the KRG

has a population of about six million and Rojava 2.2 million, surrounded by

much larger ones. And their economies are barely floating wrecks. Rojava is

well organized but blockaded on all sides and unable to sell much of its oil.

Seventy percent of the buildings in Kobani were pulverized by US bombing.

People have fled from cities like Hasaka that are

close to the frontline. The KRG’s economic problems are grave and probably

insoluble unless there is an unexpected rise in the price of oil.

The following map shows on the left Kurdish “Rojava”

and on the right the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq and Syria.

What is with Turkey and Erdogan in this matter?

Turkey’s playbook in

Syria has changed dramatically since the civil war broke out in 2011. Erdogan

was flying high at home that spring when people first took to the streets of

Damascus to protest the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. The

secularist opposition was in a slump, and Erdogan was set to embark on a

program to Islamize the country’s education system. The conflict across the

border in Syria offered Erdogan an opportunity to extend his agenda outward.

Within months, the Turkish government abandoned Assad, formerly a close

partner, and began to arm the Islamist insurgents doing battle against

Damascus. Turkey soon became a hub for Syria’s exiled opposition and a conduit

for the steady stream of foreign jihadi fighters making their way into Syria.

Eventually, Ankara turned a blind eye even to members of the Islamic State (or

ISIS), who slipped in and out of the country and sometimes sought medical

treatment there. All the while, Turkey opened its borders to millions of

refugees fleeing the fighting and built vast camps to hold the new arrivals.

The gesture was expensive but morally just, Erdogan argued, an act of Sunni

compassion and solidarity in the face of the Assad regime’s atrocities. That

narrative struck a chord with the public, and opposition to the refugee influx

remained relatively muted. All told, Turkey hosted 3.6 million Syrian refugees.

Fighting in Syria,

however, were not just Islamist insurgents but several Kurdish militias. For

Erdogan, this was bad news. In 2015, his Justice and Development Party had lost

its parliamentary majority for the first time in over a decade, owing in part

to the unexpected success of a party representing Turkey’s Kurdish minority,

parts of which had for decades fought their own low-level insurgency in the

country’s southeast. To hold on to power, Erdogan struck an alliance with a far-right

opposition party known for its strong opposition to Kurdish nationalism. The

government’s years-long peace process with Kurdish militants in the southeast

came to an abrupt end.

Erdogan’s priorities

in Syria shifted accordingly. Ankara was now determined to discourage Kurdish

efforts to establish autonomy in the region spanning southeast Turkey and

northern Syria. Attempts to unseat Assad through Islamist proxies took a back

seat to the more pressing concern of denying the Syrian Kurds a contiguous

autonomous region along the border with Turkey. In Aleppo, the Syrian rebels’

last stronghold, Turkey now enlisted insurgents who had been fighting Assad to

attack Kurdish forces instead, sapping the rebellion of its manpower and

facilitating the advance of the Syrian army, which retook the city in 2016.

That year, Turkey sent its own military into northern Syria in an effort to

contain the Kurdish militias operating there.

By 2017, Erdogan’s

about-face was complete, and Ankara was working with the Assad regime and its

allies. To the dismay of the Syrian opposition, Turkey, Russia, and Iran agreed

to create several so-called de-escalation zones. In theory, regime and

opposition in these areas would have to honor limited cease-fires, but in

practice, the regime made military gains by frequently violating the truces,

often with Russian support. In return, Damascus and its allies looked the other

way when Turkey launched a second military intervention into the Kurdish

enclave of Afrin in January 2018.

Just as Erdogan’s

domestic concerns about Kurds occasioned a shift in his objectives in Syria, so

too have domestic concerns about refugees. The Turkish president senses that

his open-door policy has become a domestic liability. His party lost control of

almost all major cities in the 2019 municipal elections—an immense blow to the

city-level patronage system upon which Erdogan built his power over the last 25

years. The rout owed something to the deepening economic crisis, but it also

reflected growing public discontent with the 3.6 million Syrian refugees still

in the country.

Once the

self-proclaimed magnanimous patron of all Sunnis, Erdogan now wants the

refugees to go home. Turkish authorities have stepped up house searches and

arrests of Syrian refugees. The state has tried to move refugees out of the

major cities, and the police have set up a hotline to collect information on

those who enter the country illegally. Some have reportedly been deported to

the Syrian city of Idlib, even as the fighting there intensifies.

Once the

self-proclaimed magnanimous patron of all Sunnis, Erdogan now wants the

refugees to go home.

Forcing hundreds of

thousands, perhaps even millions, of Syrian refugees out of the country and

back into a war zone is nearly impossible, but Erdogan thinks otherwise. His

solution, recently laid out in a speech at the UN General Assembly, is to carve

out a large buffer zone along Syria’s border with Turkey. The area would be 300

miles long and 20 miles deep, under Turkish control, and off-limits to Kurdish

forces. According to Erdogan, this “safe zone” would host two million to three

million refugees, thus ridding Ankara of a major domestic headache. It would

boast 200,000 homes, along with hospitals, football pitches, mosques, and

schools, Turkish-built but financed internationally—a setup that would provide

much-needed revenue for Turkey’s struggling construction sector at a time of

economic downturn. Securing funding for this idea is a tall order, but Erdogan

is willing to push the envelope. In September, he threatened that he would

“open the gates” and set off another European refugee crisis if he did not get

his way.

Erdogan’s proposal might

be the perfect solution for his domestic woes, but it is sure to create a host

of new problems for everyone else. His plan would send millions of Arab Syrian

refugees into Kurdish-majority areas inside Syria, not incidentally, from

Erdogan’s point of view, as changing the ethnic makeup of the region would

further undermine the Kurds. But doing so would increase Arab-Kurdish tensions,

fuel conflict in a region that has been relatively stable, and cause mass

displacement in those areas. Under international law, Erdogan cannot force the

Syrian refugees to move back, and most would almost certainly not move

voluntarily, even into a purported safe zone. U.S. strategy in Syria, which has

relied heavily on the Kurds to prevent ISIS from making a comeback, would take

a massive hit. And the plan is a godsend to the United States’ adversaries in

Syria—Russia, Iran, and the Assad regime—who believe they can stand by while

the Turkish incursion prompts a complete U.S. withdrawal, only to recapture the

area and kick out Turkey later on.

What next?

While his troops have

started to move, Erdogan will visit the United States on 13 Nov. at Trump's

invitation, a White House spokesman said. He announced on Monday that U.S.

troops had started to withdraw after a phone call he had with Trump.

Trump's decision to

withdraw troops from northeast Syria has rattled allies, including France, one

of Washington's main partners in the U.S.-led coalition fighting Islamic State.

Even Republican

Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, usually one of Trump’s staunchest

defenders, has threatened to sanction the Turkish government if it sets foot in

Syria. Erdogan, however, is likely prepared to take that risk. His rule is at

stake, and that is all that matters to him, even if it means economic penalties

for his country and yet more chaos and suffering for Syria.

Thus Kurdish leaders

are now scrambling to prepare for the worst. Gen. Mazloum Kobani, the top SDF

general, announced amid the haze of strategic surprises, diplomatic

miscommunication, and public backpedaling, that an alliance with Assad against

Turkey is “on the table.” The SDF is “ready” for talks with Assad, SDF-affiliated diplomat Sinam Mohamad told the National Interest. But Assad’s two

main backers, Russia and Iran, are towing a careful line.

The Rojava

Information Center, a media organization based in northeast Syria, confirmed to

the National Interest that pro-Assad forces are massing near Manbij and Deir ez-Zour,

but it’s not clear whether they will help or hinder the Turkish campaign. David

Ignatius, a Washington Post columnist, claimed that Assad was mobilizing his forces for an invasion of his own.

Russian foreign

minister Sergei Lavrov condemned U.S. support for the SDF, but also left the door open

for a Kurdish role in Syrian politics.

“The Americans have

established quasi-government structures there, keeping them functional and

actively promoting the Kurdish issue in a way to cause dissent among the Arab

tribes traditionally populating these territories,” he said, according to

Russian state media. “Our stance unequivocally proceeds from the need to solve

all problems of that part of Syria through dialogue between the central

government in Damascus and representatives of the Kurdish communities that have

traditionally lived in these territories.”

According to Fawri Hariri, an Iraqi Kurdish official who met with Lavrov, the Russian foreign minister promised to help

mediate between Damascus and the Kurds.

Given there earlier

pattern Russia is likely to try to reach arrangements with everybody involved.

Whereby Iran’s

established position has been to encourage the Kurds to reach a kind of

compromise with Assad to prevent any kind of Turkish invasion in that part of

Syria.

Late on Tuesday,

Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif condemned any Turkish military action, but

also brought up the Adana Agreement of 1999. In the pact, Syria had agreed to

cut off its support for Kurdish guerrillas in Turkey and expel Kurdish

nationalist leader Abdullah Öcalan.

Azizi explained the

comments as a “shift in Iran’s position from trying to reach the compromise

between the Kurds and Damascus to trying to reach a compromise between Turkey

and Damascus.”

“I think [Russia]

wouldn't be happy with a major offensive, but at the same time, if there was a

smaller incursion, they would not be as opposed to it as they publicly state,”

Signaling a further

potential shift in the region's power balance, the Kurdish-led forces said they

might start talks with the Syrian government and Russia to fill a security

vacuum.

The SDF, which has

vowed to defend itself against any perceived Turkish incursion, called on the

US-led coalition and the international community to implement a no-fly zone

over northern Syria similar to the one implemented in Iraq.

But the latter is not

happening for example at the time of writing heavy smoke was seen billowing

from an SDF position, hit by Turkey airstrikes on the outskirts of Ras Al Ayn:

With many people seen flying Ras Al Ayn:

Civilians are also fleeing several other places like,

as seen next, the border town of Serekanyie as

Turkish warplanes and artillery target positions of the Kurdish forces.

The

Turkish Army is also bombarding SDF positions in Qamishli City, where hundred of thousands of civilians live.

What happens in the

longer term depends on whether the US keeps a military presence in other parts

of the northeast and east.

A full withdrawal

could expose the area to the risk of more Turkish advances, an IS revival, or

attempts by Iranian- and Russian-backed government forces to gain ground.

As evening fall today:

For updates

click homepage here