Because language

contact and geographical displacement imply various kinds of social change, it

is inferred that the contact between "Indus" language and the Munda/Para-Munda

languages was somewhat intense, implying a fairly high

degree of socioeconomic integration. The same was true later, of the contact

between OIA (presumably both the inner and outer varieties) and the local

languages, which presumably included both "Indus" and Para-Munda. In

both cases, if "Indus" and Para-Munda were languages of the

Indus Valley culture (respectively a local language and an interregional lingua

franca), then it would not be surprising if such contact occurred; nor would it

be surprising if early speakers of Indo-Persian interacted with the local

people in similar ways, given the need of pastoralists for agricultural

produce. Interactions between Dravidian and Indo-Persian speakers appear to be

somewhat later, and perhaps occurred first in a place

called ‘Sindh’.

In fact

Dravidian languages were present probably by 1000 BCE if not earlier. And

Dravidian place name suffixes are found in Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Sindh, and

Dravidian may have played a role in the southern cities of the Indus Valley

culture in Sindh and Gujarat. Outer Indo-Persian languages probably appeared in

this area by the mid-second millennium BCE or earlier.

Following are early languages in contact with each other

in various parts of the subcontinent:

The Prakrits provide some suggestions of regional dialect variation

but by end 2004, we have no knowledge of the

relationship between the literary tradition that has been handed, and the

actual usage of the majority of Indo-Persian speakers. Evidence

suggests that regional variation was probably greater, even from the

earliest times, than one can infer from any analysis of the traditional texts.

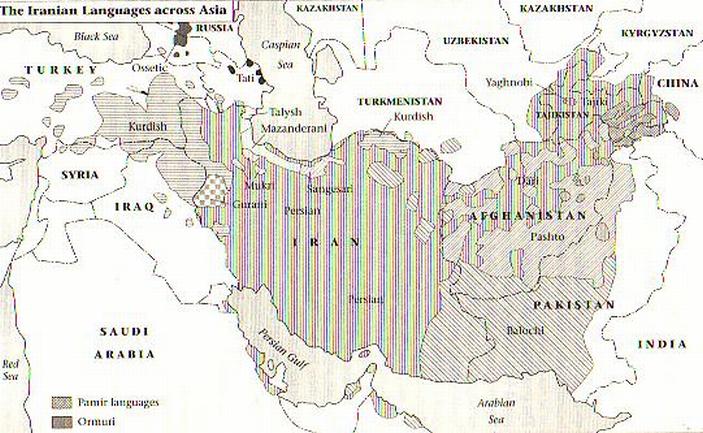

The Nuristani or Kafiri languages, a separate branch

of the Indo-Iranian languages, may have found their way to their current

locations a few centuries earlier. Korku, a North Munda language listed above,

is spoken in Nimar District of Madhya Pradesh. And Speakers of outer IA may

also have entered the Kosala/Avadh area from the Narmada across the Vindhya

complex, via the valleys of the Son and other rivers.

But for all its ups

and downs, today (January 2005), Persian

is still spoken beyond the borders of Iran in the northern half of Afghanistan

(as Dari, `courtly'), and beyond that in Tajikistan (as Tajik), famed for

its poetry.

Next as we will see particularly the attractions of the Buddha's

teachings caused the spread of Sanskrit in its path northward,

round the Himalayas to Tibet, China, Korea and Japan (for all we know,

Buddha lived in the fifth century BC, in the lower valley of the Ganges,

speaking a Prakrit known as Magadhi). The faith he founded spread all over

India and §ri Lanka, as well as into Burma, its

scriptures largely written in a closely related Prakrit, Pali, but also, more

and more over time, in classical Sanskrit. Besides the spread to South-East

Asia, the most influential path that Buddhism took was to Kashmir, and back to

the homeland of Sanskrit itself in Panjab and Swat.

Hence in the first

century AD Buddhism, with its attendant scriptures, spread northward, perhaps

here again trekking back up the historic route that Sanskrit speakers had used

to enter India over a millennium before. But past Bactria, instead of turning left

into the central Asian steppes, it turned right and, picking up the Silk Road,

headed into China. Received by the rising Tang dynasty, and ultimately

propagated by them, Buddhism became coextensive with Chinese culture. Thence it

was ultimately transmitted, along with its Sanskrit and Pali scriptures, to

Korea and Japan, its most easterly homes, arriving at the end of the sixth

century.

Other, closer, areas

took much longer to receive the doctrine, borne as ever by its vehicles Pali

and Sanskrit. Nepal had been part of the early Indian spread of Buddhism under

Asoka, in the third century BC; but the first Indian monk invited into Tibet, Sdntaraksita, came in the second half of the eighth

Sanskrit, then, has a far-flung history, and has been in contact with cultures

conducted in other languages all over southern, eastern and central Asia. And

interesting generalisation emerges. Nowhere has this

linguistic contact led t loss or replacement of other

linguistic traditions, even though Sanskrit has always been central to new

cultural developments wherever it has reached. This record makes a striking

contrast with the impact, too often devastating, of languages of large-scale campaigning

civilizations, such as Greek, Latin, Arabic, Spanish, French and English (for

the latter see part 3 below).

In 1979 Victor Sariyiannidis a Greek Archeologist, discovered 20,000

pieces of gold jewelry in Tilia Tepe (Bactriana)

in Afghanistan, and proceed next to investigate what he said was the home of

Zoroastrianism. In 2000 BC, tribes from different parts of the ancient world,

particularly from northern Syria, were forced to leave their land because of a

major drought that affected some parts of the world. They arrived at what was

then the fertile delta of the Amu Daria River in southeastern Turkmenistan and

settled there.

On the banks of this river they built their capital, Gonur, whose

palace had an entrance similar to that at Knossos, reported Sariyiannidis. Claimed to be the cradle of

Zoroastrianism, a the temple of water was built on this lakeshore.

A grant by the Greek state in 1996 Greek allowed

students to join in the effort, “but none ever arrived,” said Sariyiannidis returning back to Greece late

2004.

The origin of

Sumerian is obscure; only some Georgians claim that their language is related,9

but the claim has not been widely accepted. Whatever their previous history,

there was evidently a lively set of communities active in southern Mesopotamia

from the fourth millennium Bc, absorbing the gains

from the then recent institutionalisation of

agriculture, and establishing the first cities. (See part 4 below)

Thus part of Mesopotamia, had in

fact already been dead for another 1300 years when those documents from

Sennacherib's library were written. But it turned out that the only way to

understand Akkadian cuneiform writing was to see it as an attempt to

reinterpret a sign system that had been designed for Sumerian use. The

intricacy, and probably the prestige, of the early Sumerian writing had been

such that any outsiders who wanted to adopt it for their own language had

largely had to take the Sumerian language with it.

This was not too big

a problem in cases where signs had a clear meaning: signs that stood for

Sumerian words were just given new pronunciations, and

read as the corresponding words in Akkadian. But Akkadian was a very different

language from Sumerian, both in phonetics and in the structure of its words.

Since no new signs were introduced for Akkadian, these differences largely had

to be ignored: in effect, Akkadian speakers resigned themselves to writing

their Akkadian as it might be produced by someone with a heavy Sumerian accent.

Sumerian signs that were read phonetically went on being read as they were in Sumerian, but put

together to approximate Akkadian words; and where Akkadian had sounds that were

not used in Sumerian, they simply made do with whatever was closest.

So Sumerian survived its death as a living language in

at least two ways. It lived on as a classical language, its great literary

works canonised and quoted by every succeeding

generation of cuneiform scribes. But it also lived on as an imposed constraint

on the _expression of Akkadian, and indeed any subsequent language that aspired

to use the full cuneiform system of writing, as Elamite, Hurrian, Luwian,

Hittite and Urartian were to do, over the next two millennia. It is as if

modern western European languages were condemned to be written as closely as

possible to Latin, with a smattering of phonetic annotations to show how the time-honoured Roman spellings should be pronounced to give

a meaningful utterance in Dutch, Irish, French or English.

By 260 Bc Persians and Indo-Greeks

(first led by Diodotus) in Bactria, had declared themselves independent. At

just about the same time (and possibly caused by this rebellion) the

Iranian-speaking Parthians thrust south from the eastern shores of the Caspian

into the plateau of Iran. A century later, in 146 BC, Mithradata

I of Parthia completed the job, and drove the Seleucids out of the rest of

Iran, taking Mesopotamia for good measure. Ten years later, as it happened, the

Indo-Greek kings of Bactria were overwhelmed by a Scythian (Saka) invasion from

the north, shortly followed by the Kushdna (also

known as Tocharians or Yuezhi) from the north-east.

In 1979 Victor Sariyiannidis a Greek Archeologist, discovered

20,000 pieces of gold jewelry in Tilia Tepe (Bactriana)

in Afghanistan, and proceed next to investigate what he said was the home of

Zoroastrianism. In 2000 BC, tribes from different parts of the ancient world,

particularly from northern Syria, were forced to leave their land because of a

major drought that affected some parts of the world. They arrived at what was

then the fertile delta of the Amu Daria River in southeastern Turkmenistan and

settled there.

On the banks of this river they built their capital, Gonur, whose

palace had an entrance similar to that at Knossos, reported Sariyiannidis. Claimed to be the cradle of

Zoroastrianism, a the temple of water was built on this lakeshore.

A grant by the Greek state in 1996 Greek allowed

students to join in the effort, “but none ever arrived,” said Sariyiannidis returning back to Greece late

2004.

Finally the advent of the Romans in the west, and the

Parthians in the east, in the middle of the second century BC, meant that Greek

was challenged. It responded in different ways. To Latin, it yielded legal and

military uses, but very little else, so that Syria, Palestine and Egypt found

themselves now areas where three languages or more were in contention. But

before Parthian, which was a close relative of Persian (and whose speakers

shared allegiance to the Zoroastrian scriptures, the Avesta), Greek was

effectively eliminated, while Aramaic had something of a resurgence at least as

a written language. Its use went on to inspire all but one of the writing

systems henceforth used for the Iranian languages, Parthian and Persian

(Pahlavi) in the west, Khwarezmian, Sogdian and the

Scythian languages Saka and Ossetic in the east, as well as for the Avesta

scriptures themselves. The one exception is Bactrian, later to become the

language of the Kushana empire (first to second centuries AD), written in the

Greek alphabet. This shows the lasting cultural influence of

apparently independent Greek dynasties in the far east, whom

the Kushâna supplanted.

Aramaic was by now an

official language nowhere, and a majority-community language only in the

Fertile Crescent. Nevertheless, it remained the predominant language over this

large area for almost a thousand years until the seventh century AD, when a

completely new language overwhelmed it.

This was Arabic,

brought with Islamic inspiration and a fervent will by the early converts of

the prophet Muhammad.

Sanskrit and Ancient Culture in Asia

The Spread of English in Asia plus the Rest of

the World

For updates

click homepage here