The lost Uma (Islamic nation) as “a

minimum” demand on the World

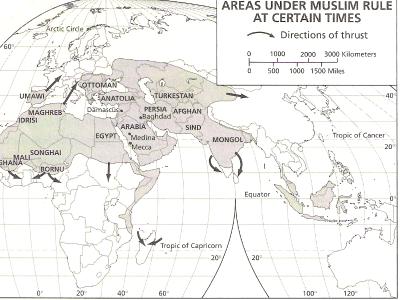

On the walls of many a geography

teacher in the Muslim realm hangs a map, depicting all areas of the world that

are, or were at one time, under Islamic sway. That map shows a contiguous

Muslim umma, or world, extending from West Africa to

Central Asia and from Eastern Europe to Bangladesh, with an outlier in

Southeast Asia. It includes most of Spain and Portugal as well as Hungary,

Romania, Bulgaria, and Greece, much of India and part of western China. It

prompts memories not only of Islam's global reach but also of its

early culture whose achievements in science and mathematics, architecture and

the arts exceeded those of Europe. Refer to this map, and even

"moderate" Muslims tend to become quite agitated. "I remind

myself daily of the humiliations we have suffered and the lands and peoples of

God we have lost," a teacher at an otherwise modern, well-equipped school

told me in 2000 when I was researching the history of Globalisation.

"This map is our inspiration, our minimum demand on the world." This

sense of shame and mortification is widespread, if not universal, in the

contiguous Muslim world: Muslims once ruled an Ottoman Empire that reached from

presentday Turkey to the gates of Vienna and a Mogul

Empire that extended from modern Pakistan to Bangladesh. They lost Iberia and

they were ousted from almost all of Eastern Europe.

They were battered by the Crusaders and colonized by the Europeans and the

Russians, whose geometric boundaries of administrative convenience created

eventual states of impractical configuration (Iraq was one of those states).

And then the West's voracious appetite for oil brought foreign economic,

cultural, and political penetration of what remained of the Islamic realm, even

of the holiest of lands, the Arabian Peninsula, site of Mecca and Medina.

I was unaware at the

time of the portent of those sentiments, they however dawned on me as soon I

encountered radical Islam in context of my postcolonial research one year

later. In the annals of History, what was done to Islam and Muslim peoples is

proportionately no more dreadful than what was done by European, (and Arab)

enslavers to Africans, American settlers to Native Americans, Belgians to

Congolese, and Germans to Jews.

However while al-Qaedaism has made significant

inroads in recent years, only a minority of the world's 1.3 billion

Muslims adhere to its doctrine. Many sympathize with bin Laden and take

satisfaction at his ability to strike the United States, but that does not mean

they genuinely want to live in a unified Islamic state governed along strict

Koranic lines. Nor does anti-Western sentiment translate into a rejection of

Western values. Surveys of public opinion in the Arab world, conducted by

organizations such as Zogby International and the Pew Research Center for the

People and the Press, reveal strong support for elected government, personal

liberty, educational opportunity, and economic choice. Thus, even those who

believe "Islam is the solution" disagree over precisely what that

solution might be and how it might be achieved.

By the same token, no

amount of behavior modification on the part of the Western world or the United

States can undo what history has wrought, and there

is no way to return the planet to the circumstances represented by the map

below. Not even a complete cessation of oil exports and the total withdrawal of . all Westerners and Western interests from Saudi Arabia

would be enough to satisfy bin Laden and his associates, where nothing short of

a theocracy of the Khomeini variety will do. Indeed, Khomeini himself made a

move that reveals the intent of those who espouse the true faith: in 1989 he

issued a fatwa that reached beyond the world of Islam, the umma,

by proclaiming a death sentence against a British author living in the United

Kingdom for a work allegedly containing blasphemy.

It is also instructive

to note that the contiguous region where Islam prevails today (thus the area

shown minus Iberia and most of Eastern Europe; Islam no longer rules but still

has strength in India) coincides remarkably with the world's harshest desert

climates. Indeed, the harshest forms of Islam seem to prosper in the toughest

environments: Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Sudan; the milder forms of it appear to

predominate under more moderate environments in Indonesia, Malaysia, and

Bangladesh. This is not to suggest a causative relationship, but it relates to

another observation of the spatial character of the faith, which is that its

core area remains most fundamentalist while the periphery (not only Indonesia

but also Turkey, Morocco, and Senegal) tends to be more temperate. This may be

taken to a larger scale: on the Arabian Peninsula itself, coastal Dubai, where

women (unlike Saudi Arabia) may drive, and Oman, where some schools admit girls

as well as boys, conditions in Islamic society vary. In the Middle East,

Saddam's Iraq was a secular state under the Sunnis' harsh rule; its leaders

wore business suits or military uniforms, not religious garb. In Lebanon, about

one-third of the Arab population remains Christian (down from 50 percent a half

century ago), and even some Palestinians remain Christians today. In the

Maghreb, the Atlas Mountains form a cultural divide as well as a physical one:

the coastal zone with its more cosmopolitan cities and towns and their busy

bazaars are a far cry from the Berber interior and its villages and caravans.

Does this mean that

moderation has a chance, that urbanization, migration, globalization, and

economic interaction will eventually temper the rage that accompanies the

revivalism driving Saudi Arabia's angry conservative clerics, their fiscal

sponsors at home and their Wahhabist allies abroad?

It does not appear so.

Islam's holy book,

like the Bible, makes discouraging and well as difficult reading. True, it

contains hopeful sentences such as "There shall be no compulsion in religion"

(Quran, 2:256), but anyone hoping that the contradictions familiar to Bible

readers may be fewer in this holy book will be disappointed. In fact, the Koran

instructs observant Muslims to despise nonbelievers. It has denunciations

of those who qualify as "infidels," warnings against interaction

with "unbelievers" and promises that "those that deny Our

revelations will burn in fire ... no sooner will their skins be consumed than

We shall give them other skins, so that they may truly taste the scourge"

(Quran, 4:55).

The number of Westerners in the Muslim world, however, is dwarfed by the millions of Muslims who are streaming into so called Western countries as immigrants. A proportionately large Muslim immigration stream arrived in Europe, and continues to do so. Europe, too, had clusters of Islamic population long before this latest invasion began: the Ottoman Empire left behind millions of converts in Eastern Europe whose descendants now make up 80 percent of the UN-administered territory of Kosovo, 70 percent in Albania, 43 percent in Bosnia, and 30 percent in Macedonia. But the total in these small countries is dwarfed by the millions who have recently come to France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Spain. In 2005, Europe as a geographic realm had an estimated Muslim population of about 30 million, more than 5 percent of its total, and Western Europe alone had 15 million (by comparison, the numbers of Westerners in Muslim countries are counted in the tens of thousands).

Europe's Muslim population has diverse sources. The majority of Germany's approximately 4 million Muslims are Kurds from Turkey. Many of the United Kingdom's more than 2 million Muslims come from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and North and West Africa as well as Southwest Asia. The leading source of France's nearly 5 million Muslim immigrants is Algeria. Spain has taken in nearly 1 million Muslim immigrants, mostly from Morocco, many of whom have entered the country illegally across the Strait of Gibraltar.

The majority of these immigrants are politically aware and culturally insular. They continue to arrive in a Europe where native populations are stagnant or declining, where Christian religious institutions are weakening, where secularism is rising, where political positions and attitudes often appear to be anti-Islamic, and where certain cultural norms are incompatible with Muslim traditions. Many young men are unskilled and uncompetitive in countries where unemployment is already high, get involved in petty crime or the drug trade, are harassed by law enforcement, and turn to their faith for solace and reassurance. They also sometimes fall under the spell of radical Muslim clerics who find a ready market for their fiery sermons Unlike most other immigrant groups, Muslim communities tend to resist assimilation, making Islam not only the essence of their identity but also the inspiration for their activism.

As recently seen in the UK where new legislation had to be passed, restraining the imams and restricting their vituperative speech is difficult under European laws, which tend to protect religious pronouncements-even rhetoric inciting violence. Imams issue calls to war, order members to join al Qaeda (as Sheik Omar did in one of his London sermons), urge Muslims to murder nonbelievers (the London imam Abu Hamza al-Masri was arrested on this charge), encourage abuse of homosexuals (the court in Rotterdam ruled that such language was within religious bounds), condone physical abuse of women, and command the faithful to resist "assimilation" into the "crusader camp."

Concern over what appears to be an intensifying movement, the past few months has led European states to consider tightening their antiterrorism laws, which engendered intense debates over individual freedoms and human rights as well as angry denunciations from Muslims. Surveys indicate that public opinion in Europe supports stronger control over Muslim militancy in its various forms. Europeans in countries with larger Muslim minorities opine that assimilation and integration have failed, and that alternate solutions to the problems of coexistence must be found.

Some European governments did less than others to foster the very integration they see Muslims rejecting. The French, always culturally confident, assumed that their North African immigrants would aspire to assimilation as Muslim children entered public schools; instead, they found themselves in a dispute over the dress codes of Muslim girls, whose head cover was deemed a religious symbol and hence prohibited. The Germans for decades would not award German citizenship to children of immigrant parents born on German soil. The Spanish made it difficult for Muslims to secure permission to build large mosques in some major cities (in 2004, Seville was still resisting such construction).

The presence of large Muslim minorities and their concentration in often dismal urban housing projects created opportunities for outsiders as well as locals to plot and execute terrorist acts. The expanding network of mosques, many of them built with Saudi, Libyan, and Malaysian funds, created channels for the flow of money as well as militants (Europe's largest mosque, on the outskirts of Madrid, was paid for by the Saudis). In this respect the experience of Spain was telling. The country was shocked when it transpired that the terrorists who bombed commuter trains in early 2004, killing and wounding more than 1,200 people, were Moroccans. This action changed the outcome of the national elections a few days later, when a conservative government that had supported America's war in Iraq was defeated by a socialist who had pledged to withdraw Spain's troops from the country. In order to reduce their dependence on money from Islamic radicals, the new Spanish administration wanted to provide its own financial support for the country's 400 mosques and prayer houses. But this would counter the government's announced plans to achieve greater separation of church and state, so the plan was shelved. The presence of the new Islam in the old Al-Andalus has its ironies.

Western European security and intelligence agencies, keeping track of extremists caught up in the web of Islamic terror cells, found that some Muslim militants had gone to fight in Afghanistan during the anti-Soviet war of the 1980s. Others fought in Eastern Europe during the 1990s, when Muslims were being killed in large numbers by Croats and Serbs during the collapse of the former Yugoslavia. Still others found their way to the Caucasus to join the Chechnyan campaign against the Russians. Virtually all of these militants returned to Europe and joined terrorist cells, becoming a serious and growing problem for law enforcement. European police have thwarted numerous terrorist plans, and they report that almost every detained suspect had been in Afghanistan, Bosnia, or Chechnya.

When the United States and its allies invaded Iraq in 2003, a new opportunity to fight in a jihad presented itself, a more attractive one, perhaps, than any of the previous war zones. Press reports in late 2004 indicated that a major Iraq-related recruitment network had been established in virtually all European countries with Muslim minorities. This network was known to provide false documents, money, training opportunities, and transport to places from which infiltration into Iraq would be possible.

Then, in the Netherlands irritations in a culturally diversifying society, coupled with concerns over the rising costs associated with immigration generally, led to a public backlash that thrust a politician named Pim Fortuyn into national prominence. Fortuyn wanted to restrict further immigration and impose Dutch social norms more stringently on those already in the country, and the popularity of his views was reflected by substantial support among Dutch voters. But in 2002 someone who objected to other aspects of Fortuyn's right wing political position, not a Muslim, shot him.

Then, in November 2004, the filmmaker Theo van Gogh, was assassinated on an Amsterdam street by a Muslim terrorist, who let a statement on his body protesting van Gogh's work, which included a film decrying the mistreatment of women in Muslim society. Van Gogh had been a persistent critic of the vituperative pronouncements of Muslim clerics, the erosion of Dutch culture by Muslim immigrants, and the cruelty to animals he associated with Islamic custom. His murder had a major impact on Dutch opinion and was a reminder of the consequences a single act can have on the dynamics of society-a point undoubtedly not lost on those returning to Europe with the experience gained in Iraq and elsewhere.

Is there any positive dimension to these generally grim developments it is often noted that another part of the world with democratic traditions and a (much larger) Muslim minority has managed, despite continuing spasms of violence and assassination, to bring that minority into the democratic process, even as nationalism surged. That part of the world is India, whose population, according to its 2001 Census, is nearly 14 percent Muslim, representing the world's largest cultural minority (140 million) by far. One reason for India's remarkable success lies in the high percentage of younger people who had already sent about 1,000 European and other militants to Iraq. If these reports are accurate, an end to the Iraq campaign, in whatever form it comes, will present Europe (and other parts of the world) with still another challenge as trained terrorists return to continue their holy war.

Events in the Netherlands cast a troubling shadow over the prospects for Europe. The Netherlands had by some measures been the most liberal and accommodating among those countries receiving Muslim (and other) immigrants, its social policies, including those relating to drugs that are illegal elsewhere, creating an atmosphere of freedom and comfort. By 2004, about 1 million immigrants had settled in the country (population 16 million, and the vast majority had adapted so well to European life that the "Dutch model" was envied across the realm. But the inevitable irritations in a culturally diversifying society, coupled with concerns over the rising costs associated with immigration generally, led to a public backlash that thrust a politician named Pim Fortuyn into national prominence. Fortuyn wanted to restrict further immigration and impose Dutch social norms more stringently on those already in the country, and the popularity of his views was reflected by substantial support among Dutch voters. But in 2002 someone who objected to other aspects of Fortuyn's political position shot him, and his movement soon fell apart. Political assassinations are a rarity in Dutch life-none had taken place for centuries-and the shock was slow to ebb. Then, in November 2004, the filmmaker Theo van Gogh, distantly related to the great painter, was assassinated on an Amsterdam street by a Muslim terrorist who not only shot and stabbed his victim repeatedly, but also left a statement on his body protesting van Gogh's work, which included a film decrying the mistreatment of women in Muslim society. Van Gogh had beer: a persistent critic of the vituperative pronouncements of Muslim clerics, the erosion of Dutch culture by Muslim immigrants, and the cruelty to animals he associated with Islamic custom. His murder had a major impact on Dutch opinion and was a reminder of the consequences a single act of terrorism can have on the dynamics of society-a point undoubtedly not lost on those returning to Europe with the experience gained in Iraq and elsewhere.

Is there any positive dimension to the above developments? It is often noted that another part of the world with democratic traditions and a (much larger) Muslim minority has managed, despite continuing spasm of violence and assassination, to bring that minority into the democratic process, even as nationalism surged. That part of the world is India, whose population, according to its 2001 Census, is nearly 14 percent Muslim, representing the world's largest cultural minority (140 million) by far. One reason for India's remarkable success lies in the high in its fast-growing Muslim minority, young adults who may live in Muslim communities but who see the opportunities in India's burgeoning economy and who are adapting their religious life to the practical realities of the present. Strife between Hindus and Muslims does occur in India, sometimes over religious flashpoints such as the temple/mosque at Ayodhya.

Still, considering the dimensions of the country's Muslim population sector (in addition to the Sikh and numerous other, smaller cultural minorities), and the nationwide distribution of Muslim communities, which are present in every one of India's 28 States, the modern record of religious coexistence in India is encouraging.

Some cultural geographers and other scholars have drawn parallels to Europe where, they anticipate, a new Islam may ultimately evolve among the children of immigrants who will formulate a modern adaptation of their faith in which pragmatism rather than fundamentalism prevails. They note that Muslim immigrants in Europe attend mosques in numbers proportionately lower than those in their countries of origin, and argue that the size and numbers of new European mosques reflect recent surges in immigration rather than a growing commitment to the faith in the Islamic communities already present. The number of mosques in the militant network is small compared to the thousands of mainstream mosques across the continent, suggesting, to these observers, that the market for extremist activism remains small. Transculturation, then, could yield a more liberal European Islam that may even diffuse into, and modify, the tradition-bound Islamic heartland itself. The question is, in this fast-changing world, whether there will be time for such a slow process to succeed.

Thus as Francis Fukuyama in Wednesday's Wall Street Journal rightly contends assimilation must begin with an end to fractious multiculturalism. But he concludes, that this also means the societies themselves must change. Here then he almost echo's the position of Prince Charles, when he writes Countries, "need to reformulate their definitions of national identity to be more accepting of people from non-Western backgrounds."

I would also suggest well educated gate-keeping immigration policies, capable of admitting those of a mind to assimilate to the home culture. If that means people who would otherwise emigrate end up remaining in their home countries, is that such a bad thing? As Fukuyama posits, in those places if they are Islamic countries a social-support system exists that tends against mass radicalism (even if, as history has shown, it has not been able to prevent pockets of radicalism, and, occasionally, dominant radicalism in places like Sudan and Afghanistan under the Taliban).

Second, perhaps understandably, Fukuyama does not confront the bottom-line logic of his thesis. Why is it that Islamic culture tends less toward radicalism when Muslim identity is more of a predetermined social reality (as he contends it is in the Islamic countries), than when it is a deeply held belief system that must transcend its non-Muslim surroundings to thrive (as is the case in the West)?

President Bush, while smoke was still billowing from Ground Zero, insisted that the answer to Islamic radicalism was somehow to be found outside Islam that 19 terrorists had "hijacked a great religion." Just a week ago, during her "religion of love" encomium, Secretary Rice maintained: "We in America know the benevolence that is at the heart of Islam."

That all sounds very nice. But let's leave aside for the moment that if such things were as routinely proclaimed by high government officials about Christianity or Judaism the ACLU would be stampeding the federal courts with lawsuits decrying Establishment Clause violations.

At roughly the same time as last week's contrasting Ramadan speeches from Rice and Ahmadinejad, the imam of Mecca's Grand Mosque, Sheikh Abdul Rahman Al-Sudais, was in Dubai being honored by his fellow Muslims with the Islamic Personality of the Year Award.

But it was not long ago that Al-Sudais was heard praying "that Allah would 'terminate' the Jews, who he benevolently called 'the scum of humanity, the rats of the world, prophet killers ... pigs and monkeys' (the latter comes from the Koran). On other occasions Al-Sudais referred to Jews as 'evil,' a 'continuum of deceit,' 'tyrannical' and 'treacherous.'" In the Muslim ghettoes of Europe, the likes of Al-Sudais might often have been more influential than let's say Locke or Burke or Montesquieu.