By Eric Vandenbroeck

On 24 Dec the UN general

assembly has urged Myanmar to end a military campaign against Muslim Rohingya and called for the appointment of a

UN special envoy, despite opposition from China, Russia and some regional

countries.

It requests that UN secretary general António Guterres appoint a special

envoy to Myanmar. The latter is because the UN special rapporteur for Myanmar, Yanghee Lee, had

been banned from the country.

Thus Lee raised the suspicion that: "This declaration of

non-cooperation with my mandate can only be viewed as a strong indication that

there must be something terribly awful happening in Rakhine, as well as in the

rest of the country" (see also Four Cuts below).

The UN human

rights chief Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein told the BBC he had urged Suu Kyi to

take action after his office published a report in February detailing

atrocities that had taken place up to that point.

"I appealed to her to bring these military operations to an

end," he said. "I appealed to her emotional standing… to do whatever

she could to bring this to a close, and to my great regret it did not seem to

happen."

The UN rights chief believes Myanmar's army was emboldened when it saw

no international response to the operations against the Rohingya: "I

suppose that they then drew a conclusion that they could continue without

fear."

Suu Kyi's defenders argue that in a country where the military remains

the real power, her ability to stop the campaign against the Rohingya is

limited.

But Al Hussein makes the same observation several others have made: that

Suu Kyi tellingly refuses to even use the term "Rohingya" to refer to

the persecuted. "To strip their name from them is dehumanizing to the

point where you begin to believe that anything is possible," he said.

Myanmar and Bangladesh have agreed to send Rohingya people back to

Rakhine, in a deal that has been criticised by human

rights groups as premature and lacking safeguards for the persecuted minority.

But also known is that the local government has harvested the

crops of departed Rohingya farmers. Ministers have hinted at plans to

redistribute the land and no access has been given to independent

observers.

“Currently, people are still fleeing from Myanmar to Bangladesh and those

who do manage to cross the border still report being subject to violence in

recent weeks,” said MSF’s Wong. “With very few independent aid groups able to

access Maungdaw district in Rakhine, we fear for the fate of Rohingya people

who are still there.”

In a death rattle of democratic principles, Suu Kyi and

Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing have synchronized denials

over the scale of the carnage in Rakhine state in a series of speeches.

The world was somewhat aghast when broken her silence on spiraling

abuses against the Rohingya Muslim minority, described as “ethnic cleansing” by

UN officials, only to defend the government that she is part of, sparking

fierce criticism from former friends, allies and supporters.

“It

is incongruous for a symbol of righteousness to lead such a country,”

Archbishop Desmond Tutu said in a letter to his “dearly

beloved younger sister”. He’s the latest of several Nobel peace prize

winners to publicly rebuke their fellow laureate. “If the political price of

your ascension to the highest office in Myanmar is your silence, the price is

surely too steep,” he said.

Already in previous years, the Myanmar government has effectively

institutionalized discrimination against the ethnic group through restrictions

on marriage, family planning, employment, education, religious choice, and

freedom of movement. For example, Rohingya couples in the northern towns of

Maungdaw and Buthidaung are only allowed

to have two children. Rohingya must also seek permission to marry, which

may require them to bribe authorities and provide photographs of the bride

without a headscarf and the groom with a clean-shaven face, practices that

conflict with Muslim customs. To move to a new home or travel outside their

townships, Rohingya must gain government approval.

Like so many others who knew Aung San Suu Kyi during her struggle, and

millions more who admired her, Tutu seems almost as baffled as he is disturbed

by her stance. But as was

evident in a 2003 interview it was not the first time Suu Kyi gave air to

her prejudice in this case.

Also an incident at the very beginning of this year set the tone for an

annus horribilis in the assassination of respected lawyer Ko Ni, architect of

the NLD’s constitutional reform efforts. Ko Ni was shot in the head at Yangon

Airport while he was holding his grandson. The military-linked suspect was last

seen in the capital Naypyidaw.

Suu Kyi did not attend Ko Ni’s funeral or visit his family in downtown

Yangon in the days after the killing, a widely criticized snub which put the

already rattled Muslim community in the city on edge. Ko Ni was a Muslim but

not a prominent activist for Rohingya rights and was seen more as a principled

advocate for constitutional and political reforms.

We also know that Suu Kyi was well informed and even engaged what the

recent developments concerns. For example on 9 August 2017, the

commander-in-chief and other senior military officers met with leaders of the

Arakan National Party, the largest party in Rakhine State – a rare meeting

between the top brass and a political party. The party expressed concerns about

the security situation in northern Rakhine and requested the arming of local

Rakhine Buddhist militias. That same day, State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi

convened a ministerial meeting on the security situation in Rakhine to discuss

the recent killings and rising tensions. The following day, the government

highlighted its deployment of some 500 troops to northern Rakhine to reassure

local non-Muslim villagers and conduct patrols in the mountains between

Maungdaw and Buthidaung where militants were

suspected of having established training camps.(1)

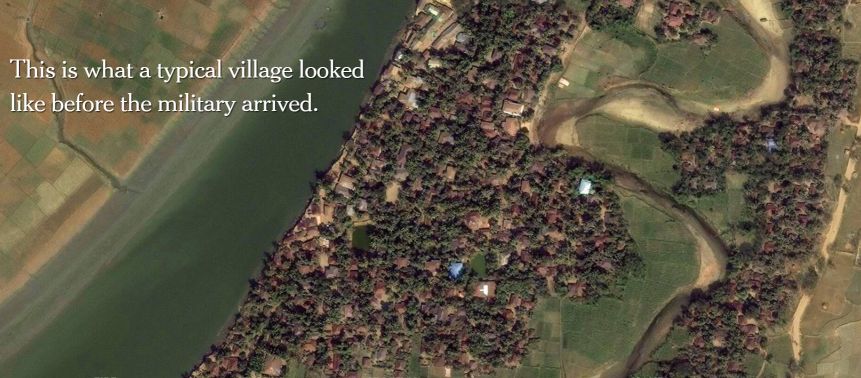

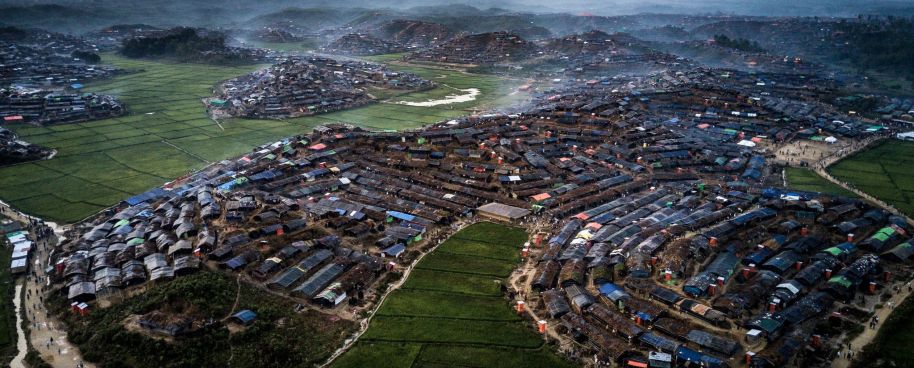

A brutal military response that failed to discriminate between ARSA

militants and the general population, followed by continued insecurity and

restrictions that have imperiled livelihoods, has driven more than 624,000

Rohingya into Bangladesh. This is one of the fastest refugee exoduses in modern

times and has created the largest refugee camp in the world. A large proportion

of Rohingya villages in the area have been systematically reduced to ashes by

both troops and local Rakhine vigilante groups that were equipped and supported

by the military.

This whereby security forces earlier drove out almost every aid group

from conflict areas in Rakhine’s Maungdaw district and only desultorily granted

access to the steadfastly neutral International Committee for Red Cross. ICRC

has operated in an almost lunar landscape of de-population where a senior ICRC

official recently observed “life

has stopped” for those left in the area.

The government compounded this disdain for foreign humanitarian actors

by charging them with complicity in support of ARSA militants, an affront to

their professional impartiality and a sop to Rakhine nationalist rhetoric that

routinely falsely alleges that international aid workers only assist Muslim

communities.

Conflicting scholarship on the

issue

The first one runs into when trying to research the above subject is the

positioning of an analysis in the safety of the center, he is careful to avoid

any real commitment to the people who are suffering. But the center is a

relative concept and the center for the analyst is far different to the center

of the people involved in the conflict. The scholarly researcher thus often

constructs the center by putting two things alongside each other as if both

have equal and exactly opposite power to determine outcomes. The Rakhine

against the Rohingya; the tenacity of the Rohingya to protect their

self-identification vs the Rakhine and Burmese tendency to denounce it.

Take, for instance, the NGO CDA’s 2016 Reshaping

Engagements: Perspective on Conflict Sensitivity in Rakhine State. Despite aiming “to serve as a platform to

build common understanding across stakeholder groups on the current conflict”

and “provide a basis for joint action”, the report does not actually consider

the perspective of Rohingya. In fact, it does not even mention the word

‘Rohingya’ preferring to simply use the term ‘Muslims’. The report mentions nothing of ethnic

cleansing, or the long history of state exclusion of the Rohingya. Instead, it

focuses on ‘breakdowns in communication’ and ‘competing agendas’. The author

has since gone on to publicly

defend the military and Aung San Suu Kyi. In

another conflict analysis produced by the Harvard Kennedy school for

Proximity Designs, the author similarly nervously approaches the subject of

ethnicity, noting that Rohingya is a ‘controversial’ title and preferring to

use the term ‘Muslim’. Although acknowledging that ‘Muslims’ and Rakhine are on

unequal footing, the report still falls into the bi-polar Buddhist-Islam

modality while barely touching on the role of the state and capital – “[W]ith a lack of many close links between the Muslim and

Buddhist communities, the recent violence has further frayed any trust… It is

difficult on the Burmese side to fully recognize this lack of parity of damage.

It is difficult for the Muslim side to admit that their actions have, at times,

also inflamed the situation.’ Another

major project on conflict analysis from Deakin University Australia also

insists on using inverted commas when talking about the Rohingya. Once again,

the research predominantly focuses on the grievances of Buddhists and Muslims

and ways for improved engagement.

What is also remarkable about the Rohingya crisis and what makes it

unique in comparison to the long list of historic ethnic insurgencies is the

way in which the Central Burmese called Bamar have

organically rallied around the government and military. From anti-government

rallies, the last year has for the first time seen mass pro-government rallies.

So too, large numbers of Bamar across many classes

have been involved in online harassment campaigns of anyone who opposes the

brutal treatment of the Rohingya.

Many of the conflict analyses share an intellectual cynicism about the

Rohingya ethnic category. Influenced by this kind of work, several pieces have

criticized the Rohingya for their insistence on self-identification. As the

Burmese and Rakhine are trying to violently exclude Rohingya from Myanmar in a

physical and cultural sense, some western intellectuals have continued to

unhelpfully question their right to self-identification.

For example, Harvard university student wrote

in the Diplomat “[I]n even a cursory survey of Rohingya history, it is

clear that the Rohingya are not an ethnic, but rather a political

construction…. At stake are issues of legitimacy. The international community’s

use of the term ‘Rohingya’ validates the narrative of essentialising

a Muslim identity in Rakhine state”.

They argue that despite a general understanding that a part of the

Arakan Muslims had deep roots in the country and that Rakhine history cannot be

understood without its social and religious complications with Bengal from the

past down to the present, a pervasive Rakhine narrative about Muslims in Arakan

has viewed them as ‘guests’ who have betrayed the trust of their hosts by

claiming territorial ownership. The claim of a distinctive ethnicity made by

Rohingyas is, therefore, considered by them as fake.

Many such analyses give a pseudo sense of complexity that seeks to water

down murderous ethnic cleansing and deny any political urgency. By maintaining

a centrism that can supposedly see all sides, the liberal analyst can always

claim the situation is complex and nuanced." Convoluted analyses that deny

this immediacy and criticise the actions of the

Rohingya are politically feeble.

No one will argue

that decolonizing the category “Rohingya” is today’s most urgent task. Yet it

seems significant that information like the above have been shared, posted, and

circulated among defenders of Daw Suu and the military’s actions in Rakhine.

Thus history has its

limits in the context of humanitarian crisis, perhaps especially so when

debates over history hinge on questions of identity.

Thus rather than

obscuring the forces and processes that allow large scale violence to occur, it

is urgent to keep these forces and their effects at the center

of accounts of the unfolding tragedy. The way events are framed and talked

about have important political ramifications at all levels. It is the political

feebleness of analysis that makes it ideal as a discursive tool on the part of

so many states and actors that wish to remain apathetic towards the Rohingya

cause.

Noteworthy is also that the 1978

“Repatriation

Agreement” with Bangladesh and

published by Princeton

University in 2014 constitutes evidence that in 1978, Myanmar acknowledged

that most Rohingya in 1978 still had

national registration cards or other documents, and thus were by and large

“lawful residents of Burma.”

The Four Cuts Strategy

revisited

The groundwork for the current catastrophe, however, had already been

laid. Since the 1970s, the Tatmadaw has carried out with impunity a “Four Cuts”

campaign against other ethnic populations, cutting off food, funds, and

information. The first reference to information

about what resulted from the “Four Cuts” was published in 2005.

The four cuts strategy was applied first in the Naga hills, and then

most devastatingly in the Shan and Karen States.The

cuts strategy involved gross human-rights abuses, including the well-documented

rape of women, torture, summary executions and more. Many witnesses have also

testified to the use of conscripted labor and the employment of civilians and

prisoners as human minesweepers. Some have suggested that it was the very

implementation of the four cuts strategy that drove the Myanmar armed forces

(Tatmadaw) to the depths of barbarity and callousness for which it has become

notorious. Others argue that such was the feeling of racial animosity against

the Karen, Kachin, Rohinghya, and other ethnic groups among the Burmese that

the Myanmars’s (Tatmandaw)

soldiers were perfectly happy to prosecute the dreadful strategy from the

start. Far from a relic of the past, this policy-which

largely victimized civilians-was officially reinvigorated in 2011, and as we

see below took on a turn for the worst in 2017 when we see what happened to the

Rohinghya villages during the 2017 campaign:

During the recent ‘clearance operation’ over

350 villages were burned down, and, according to conservative estimates by

Docter Without Borders, 6,700 people may have been killed by security

forces and vigilantes. The number of defamation cases against journalists also

spiked in 2017. Many local reporters are now operating in a climate of fear

under the elected National League for Democracy (NLD)-led government,

undercutting hopes it would champion, not repress, free speech in line with its

democratic mandate after decades of censorship under military rule.

Grim details of the military and local vigilante campaign of violence,

described by the UN as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing” (a characterisation that has now been echoed by the United

States) and by human rights groups as crimes against humanity, have been set

out in a series of detailed reports by these organisations.

They document widespread, unlawful killings by the security forces and

vigilantes, including several massacres; rape and other forms of sexual

violence against women and children; the widespread, systematic, pre-planned

burning of tens of thousands of Rohingya homes and other structures by the

military, BGP and vigilantes across northern Rakhine State from 25 August until

at least October 2017; and severe, ongoing restrictions on humanitarian

assistance for remaining Rohingya villagers.(2)

Myanmar

and Bangladesh signed a repatriation agreement on 23 November 2017 in

Naypyitaw. While it was politically expedient for both sides, Bangladesh to

signal that it will not host the refugees indefinitely, and Myanmar to respond

to charges of ethnic cleansing and ease pressure for action.

It should be noted however that Myanmar has consistently declined any

role for the UN Refugee Agency, which could mobilise

the necessary support as well as credibility in the eyes of the Rohingya and

internationally; the bilateral agreement does not require it.(3)

Beyond the risk of further abuses against the Rohingya, the authorities

have reinforced an ugly strand of nationalism that will outlast the current

crisis and could be channelled to target other

minorities. At a minimum, it will be more difficult for national leaders to

make the necessary concessions in the peace process of greater minority rights

and political and economic devolution. To this one could ad that ARSA is not

(and likely never will be) part of the peace process, given that the Rohingya

are not a recognized ethnic group.

Myanmar set its political direction early in the crisis, and, so far,

international scrutiny, pressure and diplomatic engagement has brought about no

meaningful change – not even seemingly minor concessions such as allowing UN

humanitarian access to the area or signalling

openness to international support or advice. Extremely strong domestic

political consensus on this issue has united the government, military including

in this case, a majority of the population as never before in Myanmar’s modern

history.

Reports also document

the mass rape of women and girls, some of whom died as a result of the

sexual injuries they suffered. It shows how children and adults had their

throats slit in front of their families, also

here. Skye Wheeler, the above listed researcher for Human Rights Watch who

is one of those that investigated the sexual violence allegations, said Myanmar

was denying a “terrible truth”. “The lack of acknowledgement or care the

Myanmar authorities including Aung San Suu Kyi have shown for Rohingya women

and girls who have been brutally raped by Myanmar soldiers as part of their

ethnic cleansing campaign is almost as shocking as the horrific crimes

themselves,” she said.

Thus in spite of the dire conditions in Bangladesh, worse could be to

move these people from camps in Bangladesh to camps in Myanmar. Whereby one of

the problems is that given no great power interests are going to be served in

saving the Rohingyas, in spite of some financial donations for that purpose

credible help for these people in Myanmar seems improbable.

This said, neither the

government nor security forces possess the political will to create conditions

for voluntary return and implement a credible and effective process to that

end. This raises the prospect of a long-term concentration of hundreds of thousands

of traumatized Rohingya confined to squalid camps in Bangladesh, with no

obvious way out or hope for the future.

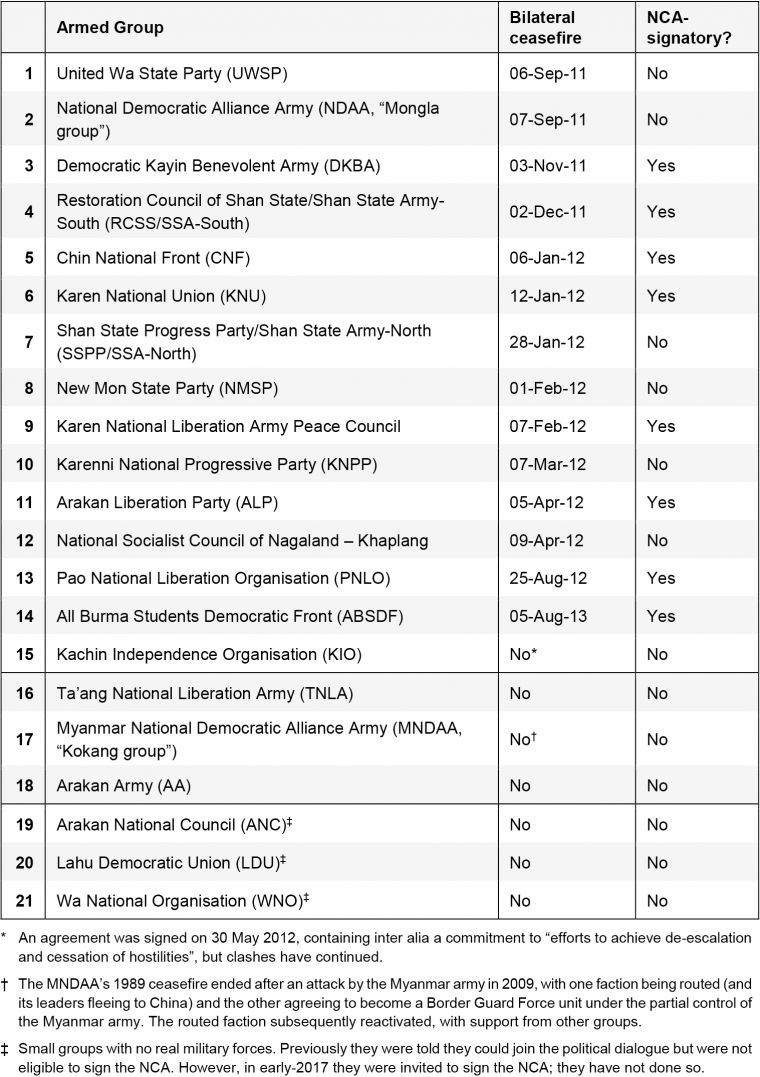

The Chinese friend is back

But it is not only the trouble with the Rohingya, to date, 80% of armed

non-state actors have refused to sign the NCA, which they view as tantamount to

surrender without any guarantees of self-determination. And there is no sign

that the government or military is willing to soften that hardline stance,

making a farce of Suu

Kyi’s 21st Century Panglong initiative as an inclusive and equal forum for

peace.

Myanmar won its independence from British

colonial rule in 1948. Sadly its history since

then has been massively unhappy. From being the best educated (apart from

Japan) country in East Asia, it spiraled down over the ensuing 65 years to

being possibly the worst educated as well as one of the poorest. The primary

cause of this decline was the world’s longest continuing civil war in which the

ethnic Bamar Buddhist majority in the central valley

has sought to dominate dozens of non-Buddhist ethnic

minorities inhabiting the mountainous borderlands.

The Bamar (Burmese) Buddhist majority

maintained its control of the heartland by extracting natural resources,

including natural gas from offshore fields that it began exporting to Thailand

around 2000 and to China around 2014. Whereby the ethnic minorities have been

able to smuggle enough resources to neighboring China, Thailand, and India to

obtain the weapons required to defend their territories against the

government’s army.

Successive military leaders have belittled, denied and squelched the

grievances of ethnic minorities, including (as seen above) chronic complaints

of military abuses and insensitivities that have perpetuated armed conflict.

A major sticking point in ongoing negotiations between the Myanmar

government, the autonomous military and the nation’s many ethnic armed groups

concerns how much autonomy should be granted to frontier areas and how that

devolution of power should be distributed among various ethnic groups.

Internal sources are telling me that with the offensive against the

Rohingya now completed, Myanmar’s military troop movements show they might be

preparing, among others, a new offensive against the Kachin Independence Army

(KIA), an armed ethnic organization that has been fighting on-and-off for

decades for self-determination. See also

here, and here.

Number of Kachin people living in Myanmar, or about 1.5% of the

country’s total population. Most live on the government-controlled

side of Kachin state, where their language and culture are strictly policed.

But China no doubt pleased by the turn of events in 2017. The year 2017

was a momentous one for China in so far as regaining its ground in Myanmar is

concerned. China not only leveraged its salience in the ongoing peace and

reconciliation process but also took advantage of Myanmar's difficulties with

the UN and the Western countries on the Rohingya crisis. Further, Beijing was

able to push Aung San Suu Kyi-led government to be part of its ambitious Belt

and Road Initiative.

Naypyidaw appears to hope that China can be persuaded at least to stay

the hand of ethnic forces. An unusual report

released by the Tatmadaw on December 22 asserted that joint ethnic Palaung Ta’ang National Liberation Army and Kachin Independence Army forces had attacked

security posts along the key oil and gas pipelines that run through

northwestern Shan state into China.

Claiming that the attacks were specifically intended to “damage the

relationship between Myanmar and China”, the report pointedly implied that the

ethnic groups were recklessly targeting the security of the pipelines and

thereby endangering China’s strategic interests.

However, none of the ethnic groups in the region has ever displayed any interest in threatening the pipelines

either during their construction or since, and it is difficult to see why

that might change today.

While admitting that the Tatmadaw had clashed with its forces in Namhkam township near the Chinese border through which the

pipelines pass, and with KIA in Bhamo in neighboring Kachin State, the TNLA was

quick to deny there had been any joint operation or that fighting had

endangered the pipelines.

More broadly, given deep mistrust and a yawning rift

between Naypyidaw and the Federal Political and Negotiating Consultative

Committee (FPNCC) over the National Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) , it would be

naïve to imagine Beijing can persuade either side to exercise significant

restraint. Indeed, there exists a real possibility that continued skirmishes

may provide a pretext or indeed real grounds for yet another coordinated

counter-offensive by the FPNCC’s northern alliance.

High-level state visits from the United States, first by then Secretary

of State Hillary Clinton in late 2011, and then President Barack Obama a year

later, and other Western countries brought Myanmar out of isolation, quickly

turning the country from an international pariah to a darling of the West.

Myitsone and other bilateral issues, meanwhile, led to a nationalistic

rise in anti-Chinese sentiment among the population and in media reports. But

2017 was the year that China bounced back to re-emerge as Myanmar’s closest and

most trusted political ally.

After a few years of “soft diplomacy” – including sponsorship of

all-paid junket trips for Myanmar politicians and journalists and contributions

to state infrastructure projects – the turning point came during the Rohingya

refugee crisis, which started in late August.

While the West strongly condemned and slapped punitive measures on the

Myanmar military for extreme human rights abuses during so-called “clearance

operations”, China kept mostly quiet while pledging to block any attempts by

the UN Security Council to impose punitive sanctions.

Then, in November, Myanmar Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung

Hlaing visited China, where he was received by President Xi Jinping and other

leaders. A couple of weeks later, Suu

Kyi also traveled to Beijing for a state visit where Xi asserted that China

is “committed” to “friendly ties” with Myanmar.

Myanmar’s attempts to find a solution to its long-running ethnic wars

have also seen China emerge as a lead actor, sidelining a host of Western

initiatives and outfits that have been involved in the peace process since

Thein Sein assumed the presidency in March 2011.

Only China has close connections with the

ethnic armed groups in the north that have refused to sign the NCA, including the heavily armed and influential United Wa State Army (UWSA), and is thus the only viable

foreign interlocutor in the peace process.

List of Main

Ethnic Armed Groups and their Ceasefire

All in all, China is increasingly seen as a “friend in need” at a time

Myanmar feels it is under new and unfair assault from the West and United

Nations. And there are certain indications that perceived as friendly

commitment will be rewarded with a new raft of economic concessions.

While the controversial Myitsone dam was not mentioned during Suu Kyi’s

visit to China, it is hardly a secret that Beijing would like to see the

suspension lifted and the project to be completed as planned when it was first

outlined in 2001.

China’s interests in Myanmar, of course, extend beyond electric power,

ethnic wars and refugees. Myanmar is China’s main outlet to the Indian Ocean,

where the Kyaukphyu port in Rakhine state and

pipelines provide a strategic hedge for its fuel and other shipments that could

be blocked at the Malacca Strait chokepoint in a conflict situation.

Myanmar is crucial corridor in

China’s US$1 trillion ‘One Belt, One Road’ global infrastructure

development initiative. In October, Minister for Construction Win

Khaing said at a forum in Singapore that “we are talking about how to

complement such [Obor] initiatives because [its]

objectives can very well complement our national objectives.”

Several other countries in the region are starting to view Obor-backed projects with apprehension and suspicion, but

Myanmar appears now to be a willing partner in the ambitious scheme.

How all these diplomatic dynamics will play out in 2018 and beyond

remains to be seen. But China is now firmly back and with a vision to stay in

Myanmar.

While in Western countries on the other hand, Myanmar’s allure as Asia’s

final frontier might have been irreparably tarnished, while the many policy

priorities of the elected National League for Democracy (NLD) government might

have been imperiled over its incompetent and pitiless response to for example

the Rakhine state crisis.

Update 2

Febr. 2018: Today there are new reports about five

mass graves. Yanghee Lee, the United Nations’

special envoy on human rights in Myanmar, said mounting evidence of atrocities

in Rakhine bear “the

hallmarks of genocide." Earlier veteran US politician Bill Richardson

said from first hand experience that Aung San Suu Kyi

lives

in 'bubble'.

1. See Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, Facebook post, 10 August 2017, http://bit.ly/2yqQYSA; “State Counsellor,

Union Ministers hold talks on security in Rakhine State”, GNLM, 10 August 2017;

“Myanmar Army Deployed in Maungdaw”, The Irrawaddy, 11 August 2017.

2. See, in particular, Amnesty International, op. cit., as well as “Destroyed areas in Buthidaung,

Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Townships of Rakhine State”,

UN Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR)/UNITAR’s Operational Satellite

Applications Programme (UNOSAT) imagery analysis, 16

November 2017; “Burma: New Satellite Images Confirm Mass Destruction”, Human

Rights Watch, 17 October 2017; “Mission report of OHCHR rapid response mission

to Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 13-24 September 2017”, OHCHR, October 2017; “U.N.

sees ‘textbook example of ethnic cleansing’ in Myanmar”, Reuters, 11

3. Crisis Group interviews, Rohingya refugees, Bangladesh,

September-November 2017; “Sales from Maungtaw paddy

kept as national budget”, GNLM, 12 November 2017; “Govt Suggests Possible Daily

Repatriation of 300 Rohingya Refugees”, The Irrawaddy, 30 October 2017;

“Tensions over Rohingya return highlight donor dilemmas”, Nikkei Asian Review,

27 October 2017; “Returning Rohingya may lose land, crops under Myanmar plans”,

Reuters, 22 October 2017; “‘Caged Without a Roof’: Apartheid in Myanmar’s

Rakhine State”, Amnesty International, 21 November 2017.

For updates click homepage

here