Where many books have

been written about New Religious Groups (often known by its derogatory term of

sect, or cult) in the USA and Europe, little is written about places like

Thailand, or the Sahara for example.

While established or standard

religion is usually seen as conservative in its attitude to change, new

religion is thought of as radical in this regard. However, in certain contexts,

as in Africa during the colonial era, it was the new religions that

attempted, albeit not indiscriminately, to preserve 'cultural capital', while

the so-called historic or mission churches, and mainstream Islam, attempted to

transform the local religious landscape. Some of the more successfully NMRs are

the African Independent Churches (AICs) - of new Islamic movements such as the

Murid Brotherhood of Senegal, and of Neo-Traditional movements such as the Mungiki (or Muingiki) movement in

Kenya.

The AICs that began

to emerge in southern Africa in the 1880s have come to be known as Ethiopian

and/or Zionist churches. The term 'Ethiopian' describes a desire for freedom,

which included the demand for equality, and self-rule for Africans in church life.

It is also a descriptive term for Africa as a chosen land. The word appears to

have been used for the first time to designate a church started in Losotho by Mangena Makone, a

former Wesleyan minister. One of the largest and most influential of the Zionist

churches, amaNazaretha (Nazareth and/or Nazerite Baptist Church) was founded in Zululand, South

Africa, in 1913, by the withdrawn and soft spoken, Mdlimawafa

Mloyisa Isaiah Shembe (1867-1935).

A former farm-hand

with no formal education, Shembe became a wellknown

member of the Methodist and later the African Native Baptist Church, which had

seceded from the White Baptist Church. He began to speak to fellow church

members of his privileged access to God's mind through dreams and visions, in

which he was commanded to leave his four wives and children and to renounce the

use of Western medicine. One of Shembe's first innovations was to baptize

converts in the sea, by triune emersion, a practice derived from the liturgy of

the Zion Church in Illinois and adapted to the local situation. It was later

adopted by many churches in South Africa and widely regarded as a means of

healing. Healing is here understood in a holistic sense, covering all aspects

of one's well-being, physical, spiritual, psychological, moral and social.

Among other practices introduced by Shembe were the removal of shoes in

worship, the wearing of long hair - a sign of resistance - abstention from

pork, night communion with the washing of the feet, and the seventh day

Sabbath.

Baptism became the

main ritual of the amaNazaretha church and the sacred

wooden drum - not used in mission churches, which regarded it as a separatist

symbol - became its main ritual instrument. The import of the hymn was also

radically changed. In this and other Zionist churches, and in the AIC setting

generally, it changed from being primarily a statement in verse about certain

religious facts into a sacred rhythm expressed chiefly through the medium of

sacred dance that paralleled Zulu dances. Following a Zulu pattern, dances were

also introduced as public expressions of faith and identity at the January

Feast of the Tabernacles and the July festival of the amaNazaretha

church itself. These festivals were held in God's earthly residences, the holy

mountains in Durban of Inhlangakazi and Ekuphakameni.

The AICs of South

Africa however, could be as critical of traditional spiritual and cultural

values and practices as they were of Western values and practices. This is

evident fro the prohibitions they introduced,

including the ban on the eating of pork, the eating of the meat of an

animal that had not been slaughtered, or drinking of the blood of animals, and

on the use of alcohol and tobacco, practices acceptable to traditionalists.

Parallels to the amaNazaretha can be found across Africa, including the

Democratic Republic of the Congo, where evidence exists of an eighteem century AIC, the Antonian movement of Kimpa Vita

(Dona Beatrice). A more recent AIC from the Democratic Republic of the Congo is

the Kimbangu Church, founded in 1921 by the prophet

Simon Kimbangu (c.1887-1951) and known as the Eglise de Jesus Christ sur la Terre par Le Prophete Sim Kimbangu (henceforth EJCSK). This is the largest AIC in

Africa.

Like other African

prophets of the period, Kimbangu preached against the

use of traditional rituals to combat evil. In contrast to other prophets 8

church leaders, Kimbangu also emphasized the

importance of monogamy and spoke of the duty on all to obey the Government.

Like the amaNazaretha and the Aladura

churches of West Africa the EJCSK introduced the use of blessed water for

healing, purification and protection. It has also become like other AICs, a

major enterprise with schools, hospitals, brick-build factories and various

other large companies.

The Belgian Colonial

Government feared the growth of this kind of movement, and, despite Kimbangu's protestations of loyalty, it had him court-martialled without any defense on charges that

included sedition and hostility to whites. He was found guilty, sentence 120

lashes and then to death. The latter sentence was commuted to life in solitary

confinement, in Lumumbashi, 2,000 kilometres

from his home in the village of Nkamba in the western

region of what was then known as Belgian Congo and is presently the Democratic

Republic of the Congo.

Throughout the

colonial era Kimbangu's followers were persecuted and

deported, and by this means and through forced migration caused by war and

poverty the movement began to internationalize. A clandestine movement also

began operating underground until 1959 when EJCSK, six months before independence

in 1960, received official recognition. By this considerable fragmentation had

occurred and Kimbangu had little time and opportunity

to reunite his Church before his death in 1951. His remains re-interred in his

home village of Nkamba, which was given the name Nkamba-Jerusalem, a place of pilgrimage.

East Africa has seen

the emergence of several new religions some of which have completely lost their

way and ended in violence, the notable being the Lord's Resistance Army and the

Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God.

The Lord's Resistance

Army (LRA), started in Acholi in northern Uganda in the 1980s when

self-proclaimed prophets announced as their mission the overthrow of the

National Resistance Army (NRA), which at the time was under the command of

Yoweri Museveni who later became President of Uganda. Among the prophets of

resistance was Alice Auma from Gulu in Acholi, who

claimed to be possessed by a previously unknown Christian spirit named Lakwena, meaning 'messenger' or 'apostle' in Acholi. In

pre-colonial and pre-Christian times possession by jok

(spirit) of humans, animals and material objects could endow them with the

power to heal or make the land fertile and turn an immoral, decadent society

into a moral and upright one. Such possession could also result in harm in the

form of moral, social and natural catastrophes. In Alice Lakwena's

case - she came to be called after the name of her possessing spirit - she

declared that her possession had endowed her with the powers to heal society.

This kind of mission

made a fit with the Christian notion of spirits, which had begun to be spread

in the region from the early years of the twentieth century. According to this

understanding, spirits were thought to heal and purify from witchcraft without

harming the one who was responsible for bringing it about, thus breaking the

cycle of retaliatory bewitching. This came to be contrasted with the

traditional spirits or joki (plural of jok) who were believed not only to heal and release from

witchcraft but also to kill the one who had perpetrated the affliction.

It was this new,

Christian understanding that, under Lakwena's

guidance, Alice tried to advance by working as a healer and diviner. She soon

resorted, however, to the traditional interpretation and in August 1986 she

organized the 'Holy Spirit Mobile Forces' (HSMF), a movement that was joined by

many regular soldiers for the purpose of waging war on the Government, witches

and 'impure' soldiers. Initial successes against the NRA were attributed by

Alice Lakwena to 'Holy Spirit Tactics' - a method of

warfare that combined modern techniques with magical practices - and led to

further support from among the Acholi population at large for her armed

resistance.

In 1987 Lakwena's army of around 10,000 soldiers, who in theory

were under the command of spirits, reached within 30 miles of the Ugandan

capital, Kampala, before being defeated by government forces. While many of the

rebel soldiers were killed, Lakwena escaped to nearby

Kenya where she continues to reside.

The ‘spirit’ Lakwena then allegedly took ‘possession’ of Alice's father

Severino Lukoya, who for a short time led the various

remaining HSMF forces - these were never fully united into one movement - until

the one time soldier in another of Acholi's rebel groups, Joseph Kony, took

over. Kony was also from Gulu and claims to be a cousin of Alice. Sometime

after Kony took control from Severino he renamed the movement the Lord's

Resistance Army (LRA).

The emphasis was

placed on the renunciation of material possessions, that were to be handed over

to the leadership, abstinence from sexual unions and the importance of silence.

Sign language was the main means of everyday communication between the members.

All of this was rationalized by reference to visions that told of the imminent

end of the world (1999 was late given for this). Usually when such a prediction

is not fulfilled devotees react in different ways. If free to do so, some move

on quietly and by putting the whole episode attempt to put together again their

fragmented lives. Others accept the explanation that the End did not come about

not because the prediction was wrong but on account of their own lack of faith,

and so on.

In the case of the

Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Command, when the prediction of the

End failed to come to pass strong differences surfaced between the members,

some deciding to leave but not before their possessions were returned to them.

Some of these members were put to death before a fire on March 17, 2000 in

which others also tragically died. Others reportedly committed suicide or were

eliminated later. Kibwetere and Mwerinde

both escaped, along with an unspecified number of members, with those who died

at an estimated number of about 780.

Since the early 20th

century thus, fully 40 percent of Africa's population moved from traditional

religions to ‘different shades of Christianity.’ During the 1970s a new wave of

Charismatic Christianity that started from within existing churches began to

sweep across Africa. But also revitalization movements grounded in the

indigenous religious tradition have continued, not infrequent in Africa among

people who are persuaded that Westernization and modernization have brought

them little but suffering and cultural degradation. While some of these

movements have a local or regional vision of revitalization of indigenous

culture, that of others is pan-African.

In the 1930s a

movement of Nigerian (Yoruba) Christians formed the neotraditional church of

the Ijo Orunmila to ensure that core elements of

their religious culture were not destroyed. Again in Nigeria, in the 1960s the

Arousa movement composed mainly of Bini beliefs and practices merged with the

neo-traditional National Church of Nigeria, to form Godianism,

which focused on belief in a single God of Africa as understood in ancient

Egyptian sources.

The Mungiki, or Muingiki, is another

revitalization movement to have emerged in recent times, also in East Africa.

Like a number of other movements in Uganda and elsewhere, not all of them

religious, Mungiki was started by two schoolboys Ndura Waruinge, grandson of a Mau

Mau warrior, General Waruinge,

with whose spirit he often communicates, and Maina Njenga, the recipient of a

vision from the God Ngai, who called him to lead his people out of bondage to

Western ideologies and ways of living. The movement began as the Tent of the

Living God movement and has appealed in the main to impoverished youth and

young men and women, who lacking the resources to enter secondary education,

are clearly inspired by the Mau Mau struggle for

their land, freedom and indigenous culture.

Following the

practice of the Mau Mau, whom they aspire to imitate

not only in their thinking but also in their lifestyle, the Mungiki

wear dreadlocks and undergo initiation by means of which they are purified or

cleansed of the impure, contaminating influences of the West. The genitals are

cut and an oath is taken that binds them to secrecy. In their prayers they ask

the God Ngai, who dwells on Mount Kenya, for mercy. The Mungiki

disciplinary code shows its rejection of Western values, including the use of

tobacco and alcohol, and the movement will often employ extremely harsh methods

to enforce this code. In what it forbids the Mungiki

movement resembles Evangelical Christianity. Although hostile to the type of

Christianity brought by the missionaries, the Mungiki

are not opposed to Christianity in principle or to Islam or to other religions.

This brings us to the

recent debates about whether Christianity or Islam is spreading faster in

Africa- clearly however they're both on the rise - and sometimes are the source

of tension. Thus enter our most current example, the "True Message" missions, allegedly

unifying the two theologies. Also engaged in traditional healing, for example a

women with menstruation problems might be prescribed 91 laps of "running

deliverance" each day. Others say they've been cured of barrenness, mental

illness, and other troubles.

One of their Pastors

explains that his father was an herbalist and that both Muslims and Christians

would come to him for healing. Although he grew up Muslim, and has been to

Mecca on pilgrimage several times, he couldn't comprehend Nigeria's sectarian strife.

He now considers himself a Christian, "but that doesn't mean Islam is

bad."

Quite the opposite. Next to his mosque is a televangelist's dream - an

auditorium with 1,500 seats, banks of speakers, a live band, and klieg lights.

On Sundays the choir switches easily between Muslim and Christian songs, and

the Pastor preaches from both the Bible and the Koran. His sermons are often

broadcast on local TV.

In Nigeria's

religious city of Jos (short for "Jesus Our Savior") the government

says 50,000 people died between 1999 and 2004 in sectarian clashes. Until a

peace deal last year, Sudan's northern Muslims and southern Christians were at

war for two decades. Thus clearly, the religious revolution is still shaking

out. And hundreds of church-sponsored banners scream out, "It's your day

of RECOVERY @ LAST where life's pains are healed" or "Jesus Christ: A

friend indeed. Even in times of need!"

Clearly, the

religious revolution is still shaking out. "People are converting rapidly,

but they don't necessarily have instruction" in the details of their

faiths, says Boston University's Professor Robert. Nor have they had "time

for their belief system to solidify." It is, she says, "still

shifting." She argues that eventually the faithful will choose one

religion or another, and the hybrids will fade away.

But the ferment is

quite evident on the chaotic streets of Lagos, which is home to some 10 million

people. Hundreds of church-sponsored banners scream out, "It's your day of

RECOVERY @ LAST where life's pains are healed" or "Jesus Christ: A

friend indeed! Even in times of need!!"

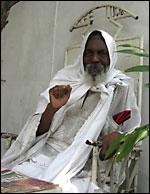

Finally, sitting in a

wrought-iron throne, swathed in silky white fabric, there is the founder

of "Chrislam" who explains that : "The

same sun that dries the clothes of Muslims also dries the clothes of

Christians." Stroking his beard, the man named Tela Tella says, "I

don't believe God loves Christians any more than Muslims."

His followers calls

him His Royal Holiness, The Messenger, Ifeoluwa or "The Will of God."

Since the religion's founding two decades ago, this small band has been

gathering almost daily to hear his message of inclusiveness - that Christians

and Muslims, "who are sons of Abraham, can be one." One the left,

Tela Tella, on the right, one of his acolyte’s:

For updates

click homepage here