By using Islam as a

basis of nationalist legitimacy, both Sadat and Mubarak abandoned the earlier eommitments to seeular modernity

that marked the Nasser era. It also ereated an

opportunity for conservative activists to promote their vision of Islam in

public life. While the ruling party-the National Democratie

Party-advocates a modernist ideology of development, both the Mubarak and Sadat

regimes consistently sought to situate their authority within a framework

linked to Islamie tradition. More importantly, the

active promotion of Islam through state-run media and the official religious

establishment has been a key factor in explaining the resurgence of eonservative Islamic polities. Not only did this contribute

to the re-emergence of the long-standing debates over the nature of Egypt's

social order, but it helps to explain the partieular

outcome. By attempting to appear more culturally authentie

than its religious opposition, state actors contributed greatly to the construetion of an Islamie social

order defined by exclusive eonceptions of national

identity and conservative interpretations of religion.1

This role of state

actors in promoting eonservative Islam helps to

explain, then, two key anomalies in contemporary Egyptian polities. The first

was the emerging dominance of Islamist polities in the aftermath of the

government's victory over its militant opposition in the 1990's. While the

militants failed to dislodge the regime, the Islamist critique had nonetheless

taken hold and the vernacular of political discourse was fundamentally

transformed. This raised the inevitable question: ''why had this occurred?"

Why weren't the victors able to defme the new 'rules

of the game'?

Related to this was a

second anomaly: why did the regime tolerate a religious establishment that was,

outspoken and moving "closer to the Islamists ideas and further away from

the official line?" 2

While conventional

wisdom tends to attribute the resurgence of Islam to popular unrest or an

inherent religiosity among the population, the approach defined here emphasizes

the important role of the state in creating an environment where Islamist

politics flourished. The state politicized not just the ulema, but the

discourse of conservative Islam. It even went so far as to support some of the

groups that would later emerge as its prlmary

opponents. In this way, the government' s politicization of religion helped to

validate the ideas and organizations associated with the Islamist movement, and

ushered in a new era of religious politics.

The implications of

this instrumental manipulation of religion have been significant.

Not only has it contributed to greater communalization of the polity, but it

has helped to create an environment where the persecution of Coptic Christians,

secular intellectuals and those with dissenting religious opinions has occurred

with regularity (and often with state complicity). The most significant victim

of the ideological battles of the last thirty years, then, has been the

conception of Egypt as a plural society. The right to differ, either

intellectually or politically, has been stigmatized and often equated with

either heresy or treason. But by relying upon coercive state structures to

constrain dissent, and by using Islam to promote political quiescence, the

state continues to exclude large segments of the population from public life,

and undercuts the possibility of developing a truly open society. Minority

rights, political development, civil society and regional stability will all

remain problematic issues for the near future.

The Islamic discourse

that now dominates in Egypt has demonstrated intolerant and exclusive

tendencies, and as such does not provide the kind of pluralist basis for a what

is in fact a diverse society. How this affects Egypt's future remains to be

seen, though it is likely that the two opposing elements of Egyptian

culture-the secular intellectual and conservative Islamic-will continue to

clash. If the state is able to improve economic well-being, increase political

participation or otherwise generate alternative sources of legitimacy, its

dependency upon religious politics may diminish, and the influence of

conservative Islam may lessen. The irony, of course, is that any effort to

genuinely open the political arena will seriously threaten the existence of the

regime, since free elections would likely benefit the Islamist opposition. In

other words, the state has limited its options by embracing conservative Islam

as a source of legitimacy.

Increased radicalism

of the Islamic networks, led Sadat to give a speech in 1979 where he denounced

the student groups by name, and argued that „those who wish to practice

Islam can go to the mosques, and those who wish to engage in politics may do so

through legal institutions." 3

Sadat next, reversed

his steps toward political liberalization in order to reign in the Islamic

movement which he had helped create.4

But by then,

religious politics had taken on a life of their own. Islamist groups had

emerged as the dominant opposition to the state, a movement ironically

facilitated by Sadat's own policies and Saudi money. And with his assassination

in 1981 by members of al-Jihad, "the genie bad struck him down." 5

Interresting, the message of both establishment Islam and the

Islamist opposition was becoming increasingly similar throughout this period.

Moreover, they all sought a common goal of "bring[ing]

Egyptian society back to Islam." 6

Unlike Ataturk's

Turkey by then (1970), Sadat's Egypt now had become firmly rooted in its

Islamic heritage. In fact the assassination of Anwar Sadat, was meant to spark

a popular rebellion coordinated by the militant group al-Jihad, but a breakdown

in communication prevented many ofthe cells around

the eountry from being activated. Members of al-Jihad

planned to eapture the radio and television building

in central Cairo, and begin broadcasting news of the uprising. This would give

other members of the organization a signal that the plan was in effect. The

failure, however, to capture the building kept many of the cell leaders in the

dark, and out of the fight. The government responded by rounding up thousands

of suspeeted militants and supporters, 300 of whom

were eharged with murder and conspiracy to overthrow

the government.

Sentences ranged from

3 years to life (plus more than eighty were excecuted),

but those that were acquitted left the courthouse chanting "the Islamic

Revolution is coming," a clear indication of conflict to come.7

The Mubarak regime's

policies reflected those ofthe Sadat era: tolerating

(though constraining) the Muslim Brotherhood, while using the official

religious establishment to promote a more obedient Islam. Unlike Sadat,

however, Mubarak would rely to a much greater degree upon the security services

to deal with the militants, which, in the 1980's and 90's, mounted a

significant challenge to the regime.

Influenced by both

the Iranian revolution in 1979, and the Afghan war against the Soviets,

political Islam emerged as an ideology capable of challenging existing patterns

of domination. Political tracts by writers such as al-Banna, Qutb, and Mawlana Mawdudi found a new generation receptive to their message.

The subsequent resurgence of a politicized Islam combined the rejectionist

ideas of these early writers with the anti Western

sentiments that bad informed Nasser's Arab Nationalism. Along with their political

and economic critique of the status quo, the Islamists offered a positive

message that drew from the cultural and religious tradition of the people. This

alternative was detined by a fear that Islam was

under attack from the West (and Westemized elites),

and that the vulnerability of the umma (community) to such an assault was due

to its having strayed from the true path of Islam.

The prescription,

then, to such ills was a "return to Islam," an amorphous slogan that

entailed a reordering social and political life in accordance with the

religious teachings of the Prophet, the Qur'an and the Sunna. (The example of

the Prophet Mohamed as it is relayed through Islamic tradition).

Although the

specifies remained vague, the Islamists believed it promised a more authentic

society, and, as such, represented an indigenous alternative to Western models

of development. It also resonated strongly with a dispossessed population, the

majority of which were preeluded from any real

opportunity for advaneement. As such, Islam became a

"potent ideology of popular dissent." 8

The initial goal was

not to destroy Islamie activism, but to temper the

extremists and co-opt the moderates, at least long enough for economic reforms

to improve living standards. There was never any intention of allowing the

Islamist groups into the political arena, or to otherwise share power with

them; rather, the state tolerated their existence as long as they did not

challenge the regime's right to rule. While Mubarak created space in the

religious and cultural spheres for those willing to cooperate with the

state-and allowed groups like the Muslim Brothers to continue providing social

services-the regime retained full control over what it perceived to be the core

issues of economic and foreign poliey.

The official ulema

subsequently worked with the regime by offering theological responses and

critiques of the militants, and, in particular, their use of violence against

fellow Muslims. The ulema continued these efforts throughout the 1990's in part

to preserve their institutional interests, and, in part, to continue their

propagation of Islam. In return for its cooperation, the Mubarak government

provided significant resourees and a degree of

independence to AI-Azhar and the Ministry of Religious Endowments.9

The Muslim

Brotherhood also worked with the Mubarek government in the 1980's, serving as

an intermediary between the state and the Islamic militants. By accepting state

authority, the Brotherhood thus was allowed to operate and published a

newspaper, al-Da 'wa (the Call), for a short period,

and continued to provide social seryices throughout

Egypt. In tbe 1980's, young activists were able to

bring their experience in university politics to the realm of the professional

syndicates.10

They made early gains

in the Engineering Syndicate in the mid-1980's, and by 1987 had won amajority of seats on that board. They made similar imoads into the doctor's and

pharmacists associations, and in 1992 they gained control of the board of the

lawyer's syndicate. Thus poliey of "mutual

accommodation" benefited the Brotherhood in its effort to re-establish

itself as the leading Islamic organization in Egyptian society.11

While the early 1980'

s were relatively quiet in Egypt, sporadic violence began in the mid to

late-1980's. The violence began with a senes of

attacks on Coptic Christians in upper Egypt. Militant groups targeted Copts for

the money that could be raised by robbing their shops, and also to strike at

the historically cosmopolitan fabric of Egyptian society. The state was slow to

respond to these attacks, even as they contributed to the communal tensions

that had been increasing since the Sadat era. In the late 1980's, the tactics

of the militants shifted, as al-Jihad began targeting government officials,

particularly, those involved in the security services. In 1987, there were four

assassination attempts on government officials, ostensibly undertaken by Islamic

Jihad.

In 1989, the Minister

oflnterior, Zaki Bar, was targeted by al-Gama'a AI-Islamiyya (the Islamic

group), Egypt's second major militant organization. Several months later, in

1990, the speaker of the Egyptian Parliament, Refaat EI Mahgoub, was

assassinated. In 1992, Farag Foda, a leading secular

critic ofthe Islamists was shot to death outside his

home in Cairo. In that same year, other militant groups struck at foreign

tourists, a leading source of foreign exchange for the government. When bombs

exploded in Cairo, it was dear that the violence of upper Egypt had penetrated

the urban life of the capital.

The Soviet invasion

of Afghanistan in 1979, and the subsequent war, had an enormous impact upon the

capability and direction of these groups. The United States and Saudi Arabia

provided significant funding and training for the Mujahadeen forces fighting the

Soviet occupation. Working with the Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI) agency of

Pakistan, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency provided upwards of$6 billion in

arms, equipment and training over the course of ten years. Moreover this was

matched "dollar for dollar" by the Saudi government.12

For its part, the

Egyptian government-like other Arab governments-actively encouraged its young

men to join the Jihad against the godless communism. Many who bad been jailed for their role in the events of 1981, left

for Afghanistan immediately upon their release. This included among others,

Ayman al-Zawahiri, the leader of Islamic Jihad and future advisor to Osama Bin

Laden. Omar Abdel Rahman, spiritual head of al-Gamaa

commonly known as the 'Blind Sheikh' was another participant in the broader

effort. The Afghan war was also an important moment in the development of an

international financial network for "Jihadi" groups. Fundraising

organizations were created with branches in Western capitals as weIl as in the Middle East to funnel money into Islamic

militancy. When the war ended, these networks and groups continued to operate,

and began redirecting their focus to other venues including Kashmir, Chechnya,

Algeria and Egypt.13

Estimates regarding

the number of Egyptians who joined the fight range from several hundred to

several thousand, although all agree that they were coordinated largely by

Islamist organizations. A number of the militant groups, particularly al-Jihad,

saw this as an opportunity to rebuild their organizations after the repression

stemming from Sadat's assassination. The Afghan war subsequently contributed to

a new level of conflict between the Egyptian militants and the state. The

capacity of both Islamic Jihad and al-Gama 'a, as well as the regularity ofviolence, increased dramatically with the return of the

mujahedin (holy warriors). These returnees had been trained in explosives and guerriIla tactics and many of them had honed their skills

in combat. Their expertise was now being turned on the regime in a manner

similar to that occurrlng in neighboring countries

such as Algeria.

Moreover, the

Egyptian military was largely unprepared to deal with this new level of

expertise and commitment. Unlike those who bad never left Egypt, these men knew

what they were doing. The attempted assassination of Interior Minister Zaki

Badr in 1989, for example, demonstrated what the security services now faced.

Although the attack failed, the use of explosives detonated by remote control

demonstrated a level of sophistication that had not existed earlier in the

decade. Of equal concern was the international funders and operatives which

gave these groups significant support, a situation created ironically by U.S.,

Saudi and Pakistani intelligence agencies.

The events leading up

to new confrontations between the state and the militants began in early 1990,

with a senes of provocations by Islamic activists.

While some actions were non-violent-including a peaceful march by the Gama'a al-Islamiyya through one

of Cairo' s slums-others were more aggressive, including a number of

anti-Christian riots and attacks on churches in upper Egypt. The government

responded by going on the offensive; it assassinated the spokesman of tbe Gama'a on the streets of

Cairo, and sent its spiritual leader, Sheikh Mubammad

Abdel Rahman, into exile. The Gama ' a retaliated by assassinating Rifaat

Mahgoub, the Speaker of the National Assembly. Abdel Rahman eventually received

a visa to the United States and set up operations in Jersey City, NI. He was

also the 'blind Sheikh' who was later convicted in a U.S. court for bis

involvement in the first attack on the World Trade Towers in the early 1990s.

And after a year and

a half of relative quiet-during which time the Gulf War occurred, the Islamic

Salvation Front (FIS), was about win-Islamic violence once again escalated.

There was a slaughter of 13 Christians in tbe Spring

of 1992 by a small faction in upper Egypt, followed by Farag Foda's assassination in June of that year.14

While these events

did little to provoke the government, it was the subsequent attack on foreign

tourists the following Fall-and the Gama'a's

announcement of a concerted campaign against Western tourism-that prompted the

government to strike back. (It is estimated that the tourist industry brought

into Egypt $3.3 Billion annually at this time).

Thousands of people

were arrested or detained without charge during these sweeps, with many being

tortured and killed in police custody. Despite govemment

gains. however, both the Gama 'a and Islamic Jihad continued their operations.

These included several assassination attempts on leading state figures, as well

as on local police and security officers. Coptic Christians were also targeted

for attack. Some of the more high profile attacks included a failed attempt on

the life of Interior Minister Hassan al Alfi, and a similar attempt on the

Prime Minster Atef Sedky.

The latter attempt proved somewhat disastrous for the militants, since the

attack claimed only the life of a local schoolgirl, which state media covered

extensively. Nonetheless, the violence was escalating, and a government victory

was far from assured.15

Many were held

without trial for several years, while those who did face charges were tried in

military courts. The govemment also passed a law

barring political activity of groups that were not registered political

parties, and actively cracked down on the activities of the Muslim Brotherhood.

As long as the

militants limited their attacks to govemment

officials and police-who bad little if any popular support-the population was

behind them. When the Gama'a shifted tacticst and started targeting foreign tourists and

Egyptian civilians (even Copts), popular support rapidly fell.

This occurred for two

reasons. On the one band, the decline in tourism seriously impacted the

livelihood of ordinary Egyptians, particularly in upper Egypt, and created

economic hardship for those whom the militants were ostensibly meant to

support. On the other band, popu1ar opinion just did not perceive as legitimate

the killing of fellow Muslims.

By late 1994 the govemment's beavy handed tactics

were beginning to pay off. By 1995, the fighting bad been effectively isolated

to the remote areas of central and upper Egypt, where the conflict

"degenerated into the timeless politics of vengeance and vendettas, an

endless cycle of killings and reprisals." 16

Militant activity

continued, though, with two attacks in September and November 1997, the latter

of which was a gruesome attack on tourists in Luxor that left 60 dead. Far from

demonstrating a resurgence of militancy, however, this attacked marked the end

of the conflict. Imprisoned members of the Gama'a

subsequently called for a ceasefire.

But while the state

proved able to deal with the security threat posed by the militants, the

ideological challenge proved more difficult to address. When the ulema

defended government policies in the 1960's and 70's, they were pereeived as puppets of thecregime.

Many of members of the ulema, refused to sanction this role, which ereated a split within AI-Azhar between the leadership and

those sympathetie to the Islamist cause. WhiIe the Iatter may have opposed

the militant's use of violence, they agreed with the Islamist eritique of the regime, and shared the Islamist vision of

social order. These internal divisions also prodded the leadership into a more antagonistie relationship with the regime. Consequently,

when the Mubarek govemment enlisted the ulema in its battIe with the militants in the earIy

1990's, it had the unintended consequenee of

empowering (and emboldening) both the centrist leadership and the conservative

ulema alike.17

The government also

provided a forum for these religious leaders to comment on political events,

yet they used it in a way that did not always benefit the regime. In April

1993, for example, a group of ulema alled upon the

government to "release the Islamist prisoners and to negotiate with the

members of radical Islam." 18

Similarly, in 1994,

Gad al-Haq attributed the rise of Islamic extremism to the state's manipulation

and control of religious affairs, and implicitly argued for a fteer hand in religious interpretation. He also became less

willing to issue blanket condemnations of attacks upon tourists and Copts, and

focused instead on issues of public morality. In taking these steps, the ulema

were presenting themselves as an alternative to both Islamic extremists and the

state. This allowed the ulema to develop an agenda of its own, and were calling

for "a return to religion." 19

While there were

limits, AI-Azhar's leverage over the regime grew more significant as the

violence became more intense. The tactics of the regime undermined its

legitimacy, and made it increasingly reliant upon whatever allies it could get.

As a result, a wide-spectrum of conservative ulema were promoted a moderate

Islamist worldview through radio, television.20

Thus, although the

Mubarak regime bad previously supported many of the secular intellectua1s who

were subsequently targeted-and provided space for them to challenge the

Islamists-the regime did little to defend them when such support became a

liability. The state's compromise with conservative religion, then, privileged

a communalist interpretation of the Egyptian nation and national identity, and

demonstrated that the tirst victim in the struggle to

maintain power was Egypt' s historical commitment to secular and cosmopolitan

norms.

At the heart of the

Islamist challenge in Egypt has been the continuing debate over how to defme the nation. At issue, is a conflict between those who

advocate a society based upon a salafiyya (or

Islamist) vision of social order-detined by the

establishment of an Islamic state and the full application of Sharia-and those

who embrace some notion of secular modernity. While the former argue that the

answer to Egypt's social ills is areturn to

tradition, the latter holds that it is the continuing influence of a stagnant

tradition that has been the source of Egypt's economic and political decline.

In the 19th century,

this debate was dominated by the reform movement of alAfghani,

Abdhuh and others. Challenged by European

imperialism, members of this movement advocated the embrace of science and

reason as a means of social revitalization. Among the more liberal elements of

this movement, religion was to be relegated to the private sphere, while the

institutions of state and society were reformed along western lines. The

premise behind this emulation of Europe was two-fold. First, developments in

science and technology were perceived to be an important element in

transforming the material conditions of Western societies, and Islamic

societies, it was believed, ought to follow suit. Second, many believed that

the unquestioning obedience to religious authority, and the lack of critical

thinking associated with it, had severely hindered the development of Arab

society. Only by embracing science and reason, then, could Arab societies

compete economically and politically with the West.

The more culturally

conservative elements in Egyptian society, however, rejected this reasoning,

and saw the European influence as an intrusion in traditional Egyptian life.

Such conservative elites perceived European values and ideas-particularly those

that emphasize individual self-interest over the interests of the community-as

largely inconsistent with those of Islam. The basic dichotomy between Egypt's

Islamists and secular intellectua1s has changed little since this era.

This was evident in

the 1990's when-in the midst of the militant violence-the debate re-emerged

over whether Egypt ought to have an Islamic or secular state. The secular

argument generally took one of two approaches. On the one.

A debate on this

issue between Islamist and secular intellectuals occurred during a meeting of

the Cairo Book Fair in 1992, the proceedings of which can be found in Misr Bayn

al Daw/a al Diniya wa al Madaniya.21 Representing the

Islamists were Muhammad Imara, Mamoun al-Hodeiby, the

spokesman for the Muslim Brotherhood, and Shekh Muhammad al Ghazzali

of AI-Azhar. On the other side were two renowned secular intellectuals, Farag Foda, the founder of al-Tanwir, and Muhammad Ahrned Khanafa. The debate was

significant for a nurnber of reasons, including the

fact that it was the first and last debate on such a sensitive topic to be

hosted by a govemment institution in such a public

forum. Moreover, it was shortly after this debate that Farag Foda was gunned down by Islamic militants outside his home

in Cairo. He argued that nowhere in the Qur' an does

it specify a particular form of government, and thus a secular government is

consistent with Islam.22

It was not that the

early Wafdists were necessarily hostile to religion.

Rather, they were concemed about the politicization

of ecclesiastic authorities, and the manipulation of religion by political

actors (particularly by the monarchy). If this first approach is wary of

religion's influence upon politics, the second approach is concemed

with the effect of politics upon religion. Authors such as Mohammad Said

al-Ashmawy are deeply disturbed over the politicization of Islam. Though he

explicitly eschews the label of secularist, Ashmawy's position is premised upon

the belief that religion (and specifically Islam) deals fundamentally with

human spirituality, not with politics.23

Other concerns raised

by secular and liberal intellectua1s deal with the ambiguity of what an Islamic

state would entail. For example, the demand for the application of shari'a, despite its apparent simplicity, is rather

misleading because there is no single interpretation of Islamic law. Rather,

there are several schools of Islarnic

jurisprudence-the Hanafi, Malaki, Hanbali, and Shafi'i-which, while similar in

most matters, do differ on various issues. Second, the secularists fear the

abuse that would be inherent in an Islamic state. 139 Once shari

'a was established, any opposition could be equated with heresy, and dissent

would "become an insolence in the face of God' s law ..that has to be

punished by applying the appropriate hadd (Quranic

punishment)."The proponents of an Islamic state-a group often referred to

as 'integralists ' -reject these arguments, and believe that a elose affiliation between religion and politics is not just

preferable, but essential. The core of their argument lies in the assertion

that Islam has never known a distinction between public and private realms, and

that all aspects ofhuman existence are meant to be

regulated by God's will as defined in the Qur'an, the Sunna (example of the

Prophet) and the Shari'a. The basic assumption within

this claim is that without religion, there can be no normative basis to

political life and, hence, no morality. Moreover, secularism is understood from

this perspective as either a matter of unbelief (kufr) or of active hostility

to religion. The alternative to an Islamic state, then, "is not a civil

state, but rather an irreligious [one]." 24

By promoting

conservative Islam for its own ends, state elites have helped to validate the

integralist (and Islamist) vision of social order, and moved the salaflya interpretation of Islam into the ideological

mainstream. This also contributed greatly to the communalization of Egyptian

politics, with dire results for the Christian minority.

Discrimination

against the Coptic Christians-which comprise the largest minority in the

country-is evident in a variety of issues ranging from the official count of

the population, l to biring procedures that exclude

Christians from holding positions of authority. There are no Christian govemors or mayors in Egypt, for example, or Cabinet level

officials. Members of the Coptic community are also unrepresented in the upper

ranks of the security services. Similarly, Cbristians

are largely absent in the realm of academia. Of Egypt' s 15 state universities,

none have a Coptic Christian in a key administrative post-either Dean or

President-and only a very few Christians hold teaching positions. Similarly,

Christian students are not allowed to attend AI-Azhar University despite its

public funding. As one of Egypt's pre-eminent universities, this type of

discrimination has long-term implications for future job prospects in such

fields as medicine, law and engineering. There is some dispute as to the actual

nwnbers of the Coptic population as weIl. Govemment figures place the

number at 6 million, or roughly 5 percent ofthe

population. Coptic activists claim a much higher figure, around 10 million.

while external sources place it at 7 to 8 million.

Other forms of

discrimination can be found in the treatment of minorities on matters of

religious freedom and marriage. While a Christian may convert to Islam, Muslims

who convert to Christianity have been subject to harassment by local law

enforcement. While such conversions are not specifically prohibited by law,

neither are hey recognized. Similarly, a Muslim woman

is legally prohibited from marrying a Christian man, though a Muslim man may

marry a Christian woman. There have also been numerous reports of Coptic girls

being abducted and forcibly converted to Islam (meaning included in a harem) by

Muslim men. While there are no reports of government involvement in such

abductions, the local police and government officials have harassed Christian

families seeking redress, and the government has clearly failed "to uphold

the law in such instances." Plus there is a law prohibiting Churching

construction (and repair) absent a presidential decree remains in force, even

while the government uses public funds for mosque construction and support.25

On New Years Eve

1999, violenee in the southem

city of AI-Kosheh led to two days of rioting. During

this period, Muslims burned and looted Coptic stores, and killed 20 Christians.

The violenee reflected long simmering tensions

between wealthy Christians and less weIl-off Muslims,

though was very much intertwined with the communalization of polities. When two

Christians had been killed in the previous year, the government rounded up

1,000 Copts-torturing many-convinced that Christians were behind the killings.26

The government's

response to the 1999-2000 violence reflected a similar unwillingness to address

the real issues. The initial trial indicted 96 defendants-58 Muslims and

38 Copts-but acquitted 92 of them. The remaining four were convieted

of only minor crimes. According to one analyst at the time, "the verdiets were intentionally light in order to avoid fanning

the flames of sectarian strife." 27

While the Egyptian

government refuses to recognize the Coptic community as a minority-and argues

that the Egyptian nation is entirely of one 'ethnic' fabric-the government has

nonetheless refused to allow for equal treatment of the Christian population. This

is refleeted in the common pereeption

among members of the Coptic eommunity that they are

second class eitizens, and, thus, not 'fully

Egyptian.' 28

Moreover, the large

amounts of daily television and radio time dedicated to Islamic programming has

in the past either demeaned Christianity or emphasized the benefits of

conversion to Islam. Similarly, Islamist newspapers, commonly denigrate

Christianity and the Coptic community, as do the sermons at Friday prayers in

mosques around the country. Each of these trends contributes to the further

communalization of public life, and has increased Coptic alienation.

These issues were

also resurrected in 2001 when an Arabic language weekly, al Nabaa, published a

lengthy story-with numerous pictures-of a defrocked priest having sex with

women at a revered monastery. A major protest erupted among the Coptic

community that included several days of demonstrations in Cairo. While the

immediate cause of the protest was the publication of the article, these

unprecedented street protests were driven largely by the community' s sense of

continued persecution. The protestor' s grievances reflected long-standing

frustration with the Mubarak regime's unwillingness to protect minority rights,

and ineluded a variety of critieisms

of both the Government and the Church leadership.

While the Mubarak

regime has sought to promote interfaith dialogue and other means to ease

tensions between the communities, the state' s promotion of communalism has had

a lasting impact upon Coptic as weIl as Muslim

identity. This has not been helped by the tendency of state actors to take

community issues up with the Coptic Church, and not with secular

representatives. And while there remain numerous Muslims and Christians willing

to reach out to one another, they frequently face opposition within their own

communities over such issues as inter-communal dialogue and the advocacy of

reform. This is especially evident in the internal divisions that exist within

the Coptic community over how to respond to both the state and the sectarian

tensions. Expatriate Coptic groups often differ with local groups over how to

approach many of the issues raised by their minority status. Similarly, the

communalism fostered by the state has constrained those in both groups who try

to promote religious tolerance and mutual understanding.

Elsewhere Farag Foda, a leading secular writer, was assassinated in 1992.

He had participated in the 1992 Cairo Book Fair forum, during which he bad he

had insulted Muhammad al-Ghazali, a leading member of Al-Azhar. The Front

subsequently issued afatwa designating Foda a kafir (beretic), the

punishment for which is death. During the murder trial, Sheikh al-Ghazali

testified to the fact that "anyone opposing the full implementation of the

sharia, as Foda did, was guilty of apostasy, and that

anyone killing such a person was not liable for punishment under Islamic

law." 29

The assassination of Foda was a galvanizing event, as was the attack two years

later on writer Naguib Mahfouz, Egypt's famed Nobel Laureate. In both cases,

the efforts by establishment clerics to ban their books or otherwise identify

them as apostates provided a warrant for their subsequent attacks by the more

radical militant groups. And although wi1ling to support secular thinkers in

their criticisms of Islamic militancy, the Egyptian regime was less willing to

aid such intellectuals when challenged by members of the religious

establishment.

For example, Nasr

Hamid Abu Zeid in 1993, a former professor at the University of Cairo, was a

scholar of Islamic studies and Arabic literature. By attempting the application

of hermeneutics to the interpretation of the Qur'an, several of his colleagues with

whom he had long differed considered his analysis heresy, and coordinated with

a group of Islamist lawyers to bring formal charges against him. While Abu Zeid

argued his case on the grounds of freedom of thought and expression (a

constitutional matter), those bringing the case invoked the rules of sharia (lslamic law), and focused on whether or not Abu Zeid's

writings were a threat to the community of Muslims. The court then ordered Abu

Zeid divorced from his wife, since "being married to an apostate from

Islam was a violation of the rights of God." 30

Muhammad Said

al-Ashmawy, the former Chief Justice of the Cairo High Court however, has found

himself in a similar predicament to that of Abu Zeid. In 1992, the Islamic

Research Academy recommended that a number of bis books be banned, and ordered

the confiscation of five specific texts. In 1996, a similar order was given for

a book he published concerning women and the veil in Islam. In this book he

argued that there is nothing in the Quran or the Sunna that require woman to

wear a veil, and that this is solely a matter of custom. The Islamic Research

Academy subsequently ordered the confiscation of this book.

See also the interview

on April 16, 2004

"Veils of Islam" (when a Muslim TV presenter was beaten by her

husband).

Other leading

scholars in Egypt were similarly targeted for attack, including author Said

Mahmud al-Qumny, whose book The God of Time, was

banned. The attack on The God of Time was part of a broader campaign against

196 books that al-Azhar deemed blasphemous. The case was submitted to the State

Security court upon the request of Al-Azhar, where al-Qumny

was subsequently charged with ''propagating ideas that denigrate Islam [under

Article 198 of the Criminal Code]." 31

The underlying debate

in each of these cases-the limits of free expression and the acceptability of

questioning revealed religion-is not new. As noted above, there has long been a

debate over the degree to which Islam is open to interpretation.

What is perhaps most

significant, though, is the government's complicity in these attacks. The

intolerance of dissenting opinions on religious matters has been legitimated by

state policies which have been designed to encourage religious piety and political

quiescence, while stigmatizing both extremism and Westernization as twin evils

to be avoided. In doing so, however, it also helped redefine the moral order of

Egyptian public life. As one writer recently commented, the emergence of

"~ influential middle class with a [traditional] mentality as weIl as the politicization of Islam" has created

a new social environment, where the idea that society should be organized

around religious principles is largely accepted and where assaults on

'deviance' by state institutions is now commonplace.

While rhetorically

committed to a secular modernity, the regime has ceded the basic debate over

religion and public life to conservative clerics. As such, the regime sought to

appropriate the message of conservative Islam, not oppose it. Since the vast majority

of the population are sympathetic to the concems

raised by the Islamists, neither the regime nor the state-controlled media

wished to defend secular principles or ideas. Moreover, the assaults on

intellectual freedoms were perceived by the regime to be peripheral to their

core economic and political concerns.32

Furthermore, aimed

at constraining moderate Islamists was the reform of the Hisba laws in 1997,

which had allow Islamists lawyers to bring cases of Islamic morality to court.

The regime has also continued to ignore the complaints of Coptic Christians,

secular intellectuals and Shi'a Muslims.

At the same time, the

Mubarak government claims to support avision of modemity that promotes tolerance, pluralism and economic

development. In short, the Mubarak regime is trying to serve as both an

advocate of secular modemity and Islamic tradition at

the same time.The inconsistency of these two trends

has generated a 'superficial hybrid,' where the successful promotion of

economic modemity would appear to entail the

promotion of critical reasoning.

Successful

modernization also requires at least some degree of independence for the realm

of civil society, and a greater emphasis upon the rule of law and accountable

government. Moreover, the success of the state in promoting a communalist

vision of society-and of depicting conservative religious belief as culturally

more authentic-has greatly affected the middle classes which have become

increasingly conservative and overtly Islamic in the last twenty years.

Despite the

government's success in replacing. top officials of the religious

establishment, moreover, the Mubarak regime has been largely unable to

eradicate the deeply entrenched conservatism that exists within these

institutions. And it is here that the state's politicization of Islam over the

last thirty years is most evident. By inviting Saudi influence and financing to

eradicate the left-and, later, to counter the Islamists-both the Sadat and

Mubarak regime helped to destroy the intellectual basis for a liberal modernist

(or humanist) Islam and discredited the idea that religion was open to

interpretation. These policies subsequently contributed to the demise of

modernist Islam within Egypt. In its stead has been placed a conservative

interpretation of Islamic tradition.

Moreover, by using

the security services (and courts) to prosecute heterodox views, the Mubarak

government has "repeatedly sent a clear message that religion is not a

private matter and that any 'deviation ftom the true

religion' will not be tolerated." 33

The influence of eonservative Islam in Egyptian public life was greatly

abetted by the changing orientation ofstate elites

that began in the 1970's. By using Islam as a basis of nationalist legitimacy,

both, Sadat and Mubarak abandoned the earlier eommitments

to seeular modernity that marked the Nasser era. It

also ereated an opportunity for conservative

activists to promote their vision of Islam in public life. While the ruling

party-the National Democratie Party-advocates a

modernist ideology of development, both the Mubarak and Sadat regimes

consistently sought to situate their authority within a moral framework linked

to Islamie tradition. More importantly, the active

promotion of Islam through state-run media and the official religious

establishment has been a key factor in explaining the resurgence of eonservative Islamic polities. Not only did this contribute

to the re-emergenee of the long-standing debates over

the nature of Egypt's social order, but it helps to explain the partieular outcome. By attempting to appear more culturally

authentie than its religious opposition, state actors

contributed greatly to the construetion of an Islamie social order defined by exclusive eonceptions of national identity and conservative

interpretations of religion.

This role of state

actors in promoting eonservative Islam helps to

explain, then, two key anomalies in contemporary Egyptian polities. The first

was the emerging dominance of Islamist polities in the aftermath of the

government's victory over its militant opposition in the 1990's. While the

militants failed to dislodge the Mubarek as the noted political commentator and

fonner-Ambassdor Tahseen Basbir

remarked, even though the Islamists were "checked in [their] bid for

power, ... the Islamization of society gained ground." 34

The Islamist critique

bad nonetheless taken hold and the vernacular of political discourse was

fundamentally transformed. This raised the inevitable question: ''why had this

occurred?" Why weren't the victors able to defme

the new 'rules of the game'? Related to this was a second anomaly: why did the

regime tolerate a religious establishment that was, at least from the early

1990's, extremely outspoken and moving "closer to the Islamists ideas and

further away from the official line?" This was particularly perplexing

given the state's complicity in high profile assaults upon intellectual

freedom, and the regime's apparent absence in the debate over social order.

The answers to these

questions are best found by moving away from a dichotomous understanding of

Egyptian politics that emphasizes a secular state vying with an Islamist

opposition-and recognizing instead the central role of official institutions in

promoting conservative Islam. The focus of this research, then, is on the

interaction of three sets of actors-the state elite, the religious

establishment and the Islamist opposition-and the manner in which this dynamic

facilitated an ideological transformation of Egyptian politics. While

conventional wisdom tends to attribute the resurgence of Islam to popular

unrest or an inherent religiosity among the population, the approach defined

here emphasizes the important role of the state in creating an environment where

Islamist politics tlourished. The state politicized

not just the ulema, but the discourse of conservative Islam. It even went so

far as to support some of the groups that would later emerge as its primary

opponents. In this way, the government.35

Politicization of

religion helped to validate the ideas and organizations associated with the

Islamist movement, and ushered in a new era of religious politics. The

implications of this instrumental manipulation of religion have been

significant. Not only has it contributed to greater communalization of the

polity, but it has helped to create an environment where the persecution of

Coptic Christians, secular intellectuals and those with dissenting religious

opinions has occurred with regularity (and often with state complicity). The

most significant victim ofthe ideological battles ofthe last thirty years, then, has been the conception of

Egypt as a plural society. The right to differ, either intellectually or

politically, has been stigmatized and often equated with either heresy or

treason. The takfir cases, for example, demonstrate the weakness of the,

government in the face of a religious communalism of its own making; by failing

to stand, up to chauvinistic tendencies within official institutions, the ruling

regime has become complicit in their actions. Moreover, the failure to

cultivate an inclusive basis of national identity-and a political culture of

tolerance and compromise-has contributed to major divisions in society and

continuing social tensions. In short, by relying upon coercive state structures

to constrain dissent, and by using Islam to promote political quiescence, the

state continues to exclude large segments of the population from public life,

and undercuts the possibility of developing a truly open society.

These findings do

not, however, imply the imminent downfall of the regime or an imminent Islamist

takeover. What it does signify is that minority rights, political development,

civil society and regional stability will all remain problematic issues for the

near future. The Islamic discourse that now dominates in Egypt has demonstrated

intolerant and exclusive tendencies, and as such does not provide the kind of

pluralist basis for a what is in fact a diverse society. How this affects

Egypt's future remains to be seen, though it is likely that the two opposing

elements of Egyptian culture-the secular intellectual and conservative

Islamic-will continue to clash. If the state is able to improve economic

well-being, increase political participation or otherwise generate alternative

sources of legitimacy, its dependency upon religious politics may diminish, and

the influence of conservative Islam may lessen. The irony, of course, is that

any effort to genuinely open the political arena will seriously threaten the existence

of the regime, since free elections would likely benefit the Islamist

opposition. In other words, the state has limited its options by embracing

conservative Islam as a source of legitimacy.

As pointed out, the

goal of the Muslim Brotherhood has always remained the same: to reestablish

Sharia rule in Egypt and elsewhere, whether by peaceful or violent means. And

now, despite the best efforts of the Mubarak regime (which, like the Nasser and

Sadat regimes before it, has tried to keep the Ikhwan at bay with a combination

of force and concessions) to limit its influence, it is gaining strength in

Egypt. However the Islamist group has now won 76 seats -- more than five times

the number it held in the outgoing chamber.

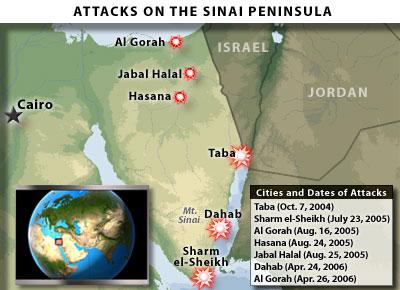

As for extremist

attacks for one, the Sinai will remain a scene violence (mostly committed by

Tawhid wa al-Jihad part of the jihadist -al Qaeda the

movement) -- plus elsewhere in the country-- occasional violent attacks against

tourist are also noticed in the map below.

In the aftermath of

the Taba bombings, more than 3,000 individuals in Egypt were taken into custody

and questioned, and following the July 22 2005, more than 2,000 were taken into

custody. However, several more high-value suspects, remained on the loose inside

the country.

And unless the

Egyptian security forces are able to penetrate the source of these attacks,

which requires more than carrying out shootouts against potential militants,

these attacks will continue.

And in Egypt as a

whole, the implications of instrumental manipulation of religion not only

contributed to greater communalization of the polity, but it has helped to

create an environment where the persecution of Coptic Christians, secular

intellectua1s and those with dissenting religious opinions has occurred with

regularity.

The most significant

victim of the ideological battles ofthe last thirty

years, then, has been the conception of Egypt as a plural society. The right to

differ, either intellectually or politically, has been stigmatized and often

equated with either heresy or treason. But by relying upon coercive state

structures to constrain dissent, and by using Islam to promote political

quiescence, the state continues to exclude large segments of the population

from public life, and undercuts the possibility of developing a truly open

society. Minority rights, political development, civil society and regional

stability will all remain problematic issues for the near future.

The Islamic discourse

that now dominates in Egypt has demonstrated intolerant and exclusive

tendencies, and as such does not provide the kind of pluralist basis for a what

is in fact a diverse society. How this affects Egypt's future remains to be

seen, though it is likely that the two opposing elements of Egyptian

culture-the secular intellectual and conservative Islamic-will continue to

clash. If the state is able to improve economic well-being, increase political

participation or otherwise generate alternative sources of legitimacy, its

dependency upon religious politics may diminish, and the influence of conservative

Islam may lessen. The irony, of course, is that any effort to genuinely open

the political arena will seriously threaten the existence of the regime, since

free elections emediatly benefitted the Islamist

opposition. In other words, the state has limited its options by embracing

conservative Islam as a source of legitimacy.

Plus while Egypt is

currently more concerned about Syria 's bid to restore its stature within the

Levant, especially regarding the Lebanese and Palestinian conflicts, than with

the rise of Iran. Al Qaeda's No. 2, Ayman al-Zawahiri, in a video marking the

fifth anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks, warned of attacks against oil

targets in the Persian Gulf region. The first manifestation of this strategy

came Sept. 15, 2006, when jihadists staged a failed attempt to strike at two

separate energy facilities in Yemen. And as al Qaeda has maintained assets in

the region it could become more active the next few months.

1 See also Fouad

Ajami, "The Sorrows of Egypt," Foreign Affairs, September/October,

1995.

2 Dalacoura,

Islam, Liberalism anti Human Rights, p. 126-7.

3 Hopwood, Egypt:

State and Society, p. 117.

4 David Sagiv,

Fundamentalism and Intellectuals in Egypt, 1973-1993, London, 1994, p. 60.

5 Fouad Ajami, The

Dream Palaces of the Arabs: A Generation's Odyssey, 1998, p. 206.

6 Zeghal,

"AI-Azhar and Radical Islam," p. 382.

7 SulIivan

and Abed-Kotob, Islam in Contemporary Egypt, p. 81.

8 Muhammad Faour, The

Arab World After Desert Storm (Washington: U.S. Institute of Peace Press, 1993,

p. 55.

9 Skovgaaard-Peterson.

Defining Islam for the Egyptian Stole, p. 220.

10 Gehad Auda, "Tbe Nonnalization of the Islamic

Movement in Egypt from the 1970's to the Early 1990's", in Marty and

Appleby, Fundamentalisms and the State, University of Chicago Press, 1994, p.

390.

11 See Geneive Abdo.

No God but God: Egypt and the Triumph of Islam, Oxford University Press, 2000.

12 George Crile,

"Charlie Did It," Financial Times, June 7-8, 2003.

13 Robert Oakley,

former-Ambassador to Pakistan, referenced in Hibbard and Litte, Islamic

Activism and US. Foreign Policy, p. 76.

14 This was reflected

in a leaked U.S. National Intelligence Estimate reported in the London Sunday

Times in February 1994 which stated that the Egyptian government was in danger

of being overthrown. The report is referenced in Jon Alterman, "Egypt:

Stable, but for How Long?" The Washington Quarterly, Autumn 2000, p. 108.

15 Lawyers Committee

on Human Rights, Escalating Attactics on Human Rights

Protection in Egypt, Washington: Lawyers Committee, 1995.

16 Ajami, The Dream

Palaces ofthe Arabs, p. 202.

17 See Julie Taylor,

"State-Clerical Relations in Egypt: A Case of Strategie

Interaction," presented at the American Political Seience

Association Annual Meeting in Washington, DC, September 2000.

18 See Steven Baraclough, "Al-Azhar: Between the Govemment

and the Islamists," Middle East Journal, Vol. 52, No. 2, Spring 1998.

19 Zeghal, "Religion and Politics in Egypt," p. 382.

20 See Judith Miller,

God has Ninety-Nine Names: Reporting from a Militant Middle East, 1996.

21 Egypt: A Religious

or CM/ State? Cairo, 1992.

22 Fauzi M. Naiiar, "The Debate on Islam and Secularism in

Egypt," Arab Studies Quarterly, Spring 1996, Vol. 18, No. 2, p. 21.

23 See Muhammad Said

al-Ashmawy, Islam and the Political Order, Washington, DC: The Council for

Research in Values and Philosophy, 1994.

24 Farid Zakariyya,

quoted in Alexander Flores, "Secularism, Integralism, and Political Islam:

The Egyptian Debate," in Joel Beinin and Joe Stork, Political Islam:

Essays from Middle East Report, Berkeley, 1997, p. 91.

25 International

Religious Freedom Report 2001, Egypt, U.S. Department of State.

26 Alberto Fernandez.

"In the Year ofthe Martyrs" Anti-Coptic Violence

in Egypt, 1988-1993," Paper Presented at the Middle East Studies

Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco, November 18-20, 2001.

27 Cited in Nadia

About EI-Magd, "The Meanings of AI-Kosheh,"

AI-Ahram Weeldy, 3-9 February 2000.

28 See

"International Religions Freedom Report, 2004" U.S. Department of

State.

29 Abdo, No God but

God, p. 68.

30 George N. Sfeir,

"Basic Freedoms in a Fractured Legal Culture: Egypt and the Case of Nasr

Hamid Abu Zayid," Middle East JoumaJ, Summer

1998, p. 406.

31 Egyptian

Organization for Human Rights, Press Release, May 1, 1997.

32 See Judith Miller

"The Challenge of Radical Islam," Foreign Affairs 72, no. 2,1993.

33 Hossam Bahgat,

"AI-Azhar is wrong, but the state is the real culprit," The Dally

Star, September 23, 2004.

34 Referenced in

Fouad Ajami, "The Sorrows of Egypt," Foreign Affairs

(September/October. 1995)

35 Dalacoura, Islam, Liberalism anti Human Rights, p. 126-7.

For updates

click homepage here