On Oct. 25, a

gathering known as the Second European Congress of Subcarpathian Ruthenians was

held in the Ukrainian province of Zakarpattia to

discuss Ruthenian secession from Ukraine. Hundreds of delegates, several of

whom belong to pro-Russian movements in Ukraine, attended the meeting, which

was led by Association of Carpathian-Ruthenians Chairman Dmitri Sodor. Sodor is

an influential Orthodox priest in the region affiliated with the Moscow

Orthodox Patriarchate. Sodor, who has been accused of separatist actions and

ties to Russia, concluded the conference with a memorandum to restore “the

Ruthenian entity” in the form of an independent Ruthenian state during the

first quarter of 2009.

The Ruthenians are an

eastern Slavic ethnic group indigenous to the Carpathian region of Central

Europe. They maintain a distinct language, culture and identity separate from

that of the majority in Ukraine, where most Ruthenians live. While statistics

vary as to the number of Ruthenians in the wider region, they number from about

1 million to 1.5 million. (Ukraine does not officially deem the Ruthenians a

minority, but rather defines them as a subgroup of the Ukrainian ethnicity.)

Most of this number are concentrated in Zakarpattia

province. As a point of reference, Zakarpattia’s

total population stands at only around 1.25 million, meaning the Ruthenian

presence and influence there is quite strong.

Coupled with other

covert and overt actions Moscow has taken in southern and eastern Ukraine,

these latest developments could tear apart Ukraine, an already divided and

dysfunctional country. And that suits Russia just fine.

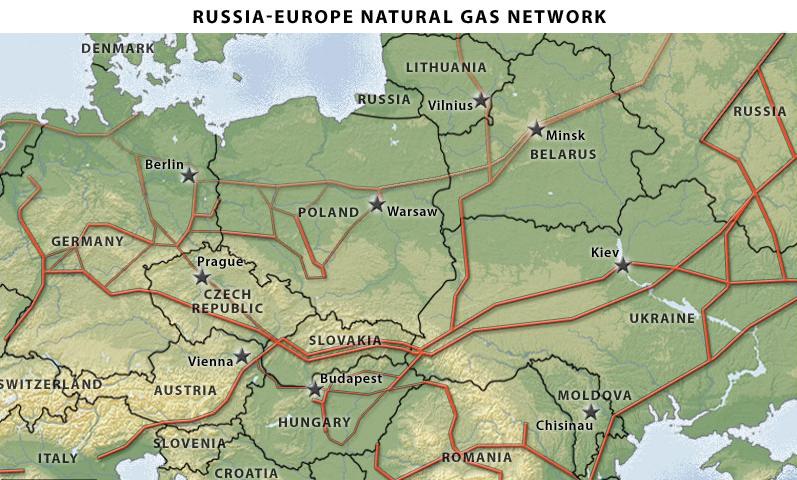

Russia also has

pushed the Ruthenians to act in an attempt to destabilize the Ukrainian

government. In addition, the Ruthenians spread across a highly strategic swath

of land in the Carpathian Mountains, which Russia considers its natural border

with the West. This is also territory through which the main trunk lines transporting

Russian natural gas pass on their way to Europe (see map underneath).

Russia has the choice

of recognizing the group (and thereby drastically escalating tensions with

Kiev) or cutting a deal with the Ukrainians to keep the country from splitting

apart, perhaps at the expense of returning Ukraine to the Russian fold.

Ukraine’s government

in turn at the moment is too shattered and chaotic to handle for example the

country’s current financial and economic problems or make any of the reforms

needed in its defunct financial, economic, military and energy sectors. However

Kiev, is not simply ignoring the Ruthenian, or Russian, moves in its western

province.

The Ruthenian ethnic

group is not limited to Ukraine, but spills over into Slovakia, Poland and

Romania. Were the Ruthenians in Ukraine to obtain independence from Kiev, it is

doubtful Ruthenians in neighboring countries would remain idle. And as these

countries are EU and NATO members, Ruthenian secession holds strategic

importance for the wider region.

Russia’s support of

the Ruthenian independence movement is not an isolated incident. When Kosovo

declared independence from Serbia in early 2008, Russia warned the West not to

recognize the breakaway province on pain of a Russian response in the same

vein. But the West ignored Russia’s request, and the Kremlin has since made it

a key imperative to offer covert support to myriad independence movements not

in line with Western interests. Given their strategic location, the Ruthenians’

move for autonomy makes quite the enticing opportunity for Moscow.

While there is no

shortage of ethnic groups with secessionist aspirations, the Ruthenians are

perfect for Russia to cultivate for two reasons. First, they would facilitate

Russian control over Ukraine, which has become Moscow’s No. 1 target for

consolidating Russian influence in its near abroad. Ukraine serves as a

strategic buffer for Russia from the West, and 90 percent of Russian energy

exports flow through Ukraine on their way to Europe, making it a crucial

transshipment hub. In short, Russia simply cannot let Ukraine fall to the West.

Second, promoting

Ruthenian independence serves as a tit-for-tat response to Europe and the

United States in the wake of Kosovar independence. Ruthenian independence is certainly not in the interest

of the EU countries of Slovakia, Poland and Romania. It would sow internal

discord in these countries (and therefore in the European Union as a whole) and

at the very least distract them from a hawkish, anti-Russian agenda.

The trans-Carpathian

homeland of Ukraine’s Ruthenians amplifies the significance of recent

developments. Trans-Carpathia is in the westernmost region of Ukraine. So far,

Russia has been spreading its influence and asserting control in southern and

eastern Ukraine, where there are large swathes of ethnic Russians, Russian

speakers and/or Russian sympathizers. If Moscow is able to challenge Kiev’s

hold in western Ukraine, the only real pro-European stronghold in Ukraine, then

Russia effectively will have broken Ukraine geographically.

It is thus no

coincidence that gatherings like the one held by Sodor and the Ruthenians are

taking place, and probably are set to increase. These delegations have caught

the attention of the Ukrainian secret service, which accuses Sodor of

compromising Ukraine’s territorial integrity. The secret service wants to track

down the origin of of these separatist groups’

funding. (Sodor’s claim that his group receives financing from local

businesspeople is in fact dubious.) In reality, the Ruthenians’ financial and

organizational support traces back to the Russian intelligence apparatus. Kiev

has begun to recognize the threat posed by these actions; the small Ukrainian

nationalist party Svoboda has called for legal action against the Ruthenian

separatists.

The Ruthenians occupy

such a strategic location that their secession could effectively scuttle any

chance for an already-fractured Ukraine to maintain political unity, letting

the country slide further into the Kremlin’s grip.

Conclusion: The Ukraine is shattered internally in nearly every

possible way: politically, financially, institutionally, economically,

militarily and socially. The global financial crisis is simply showing the

problems that have long existed in the country. In the near future, there is no

conceivable or apparent way for any force within the country to stabilize it

and begin the reforms needed. It will take an outside power to step in, which

leads to the larger tussle between the West and Russia over control of one of

the most geopolitically critical regions between the two. Russia has far more

tools to use to keep Ukraine under its control, but the West has laid a lot of

groundwork in order to undermine Moscow, leaving the future of Ukraine

completely uncertain. As for Ruthenia, Ukraine’s intelligence services might be

planning to round up the ringleaders of the Ruthenian separatists in an attempt

to squash their drive for independence.

For updates

click homepage here