AD. 25 Xuan-Zang recognised at least three distinct countries in this

region: Udra (the origin of the name Orissa), which

he said had `words and language different from Central India', Kônyodha,`with the same written characters as those of

mid-India, but language and mode of pronunciation quite different', and

Kalinga, where `the language is light and tripping, and their pronunciation is

distinct and correct. But in both particulars, that is, as to words and sounds,

they are very different from mid-India. This kind of evidence is just one

example of what makes it so difficult to depict in any detail the language map

of India in past centuries. Sanskrit influence permeated farther south, eventually

saturating with borrowed words three of the major non-‘Aryan’ languages,

Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam. Tamil, in the extreme south-east, was less

affected linguistically. And besides this gradual export of words, there had

also been, in the middle of the first millennium BC, a major transplant of a

whole community, with its Aryan language, to the extreme south. This accounts

for the presence of Sinhala in Sri Lanka. The history of the movement of people

that brought this language is not documented, but it may be reflected through

legend in the epic Ramayana, which climaxes in a military expedition to this

island (to rescue Rama's kidnapped wife Sita-rather similar to Homer's

motivation for the Trojan War, where a Greek fleet set out to rescue Menelaus's

wife Helen). About two hundred years later, in the late third century BC, the

links between Sri Lanka and the Aryan north were reinforced when Asoka sent his

son Mahinda to the island as a Buddhist missionary, so founding the Theravada

school of Buddhism which has endured to this day.

The move to Sri Lanka

may be seen as the beginning of Sanskrit's spread beyond the shores of India.

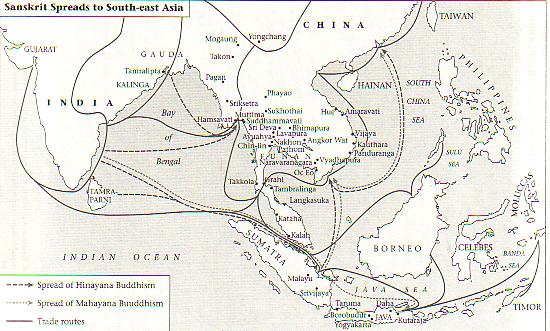

This seabome expansion makes its significance far

greater to the global story, for Sanskrit is the first example in history of a

language travelling over a maritime network, through the establishment of trade

and cultural links with peoples on the other side. In this, it can be seen as a

precursor of the spread of the western European languages in the last five

hundred years.

By the middle of the

first millennium AD, Sanskrit was spread all over South-East Asia,

including the main islands of modem Malaysia and Indonesia. There is no clear

record of how this came about. But one feature of the spread of Sanskrit is

clear: it was not a military expansion. There was never a warlike move by

Indians into Asia, even of the typical short term empires, which even in

north India never seemed to last more than a very few generations.

But if we leave aside

military ambition, the motives that have been suggested for the successes

exhaust every other possibility: refuge from imperial wars from the Mauryas and Asoka onward, piratical raids, a spirit of

adventure, the peaceful pursuit of trade, or a desire to spread sacred

learning, of Buddhism certainly, and perhaps earlier even.

Each of these has

something to recommend it, and they are not mutually exclusive. It must mean

something, for example, that the name for India current among Malays and

Cambodians was 'Kling', that is Kalinga, the coastal realm in eastern India

bloodily conquered by Asoka. There, and especially in its northern region Tdmralipta ('copper-smeared', modem Tamluk

in West Bengal), there was a tradition of producing sdrthavâhâh

or sâdhavah, `merchants', who were easily confused

with sdhasikdh, `pirates, buccaneers', proverbial in

Sanskrit for their bravery, as well as violence.

The popular Jâtaka tales of previous lives of the Buddha, composed

around this time, are also full of merchants who seek wealth in Suvarnabhûmi.

The motive for the

trade is hinted at by the Sanskrit names that they gave to parts of this

eastern world. Sri Lanka was known as Tâmradvipa,

`copper island', or Tâmraparni, 'copper-leafed'; the

land beyond the eastern ocean as Suvarnadvipa, Suvarnabhûmi, `the isle, or the land, of gold'. These names

survived to be taken up, or translated, by Greek explorers, Taprobane

for Sri Lanka, and Khryse Khersonesos,

`Golden Peninsula', for South-East Asia. There is little in these countries'

known geology to suggest that the names were well founded. But the quest for

precious metals was clearly part of the legend of such ancient navigation. One

of the most evocative tales in the Sanskrit equivalent of the 1001 Nights,

Somadeva's Kathâsaritsâgaram ('Ocean of the Streams

of Story'), recounts the quest of a Brahman, setting out for his lost loves in Kanakapuri, `The City of Gold', located somewhere beyond

`The Islands'. One of the merchants he meets on his way has a father who

returns rich from a long voyage to a far island, his ship loaded specifically

with gold.

More realistically,

there was scope for immense profit either in entrepôt business, exchanging

Indian aromatic resins (including frankincense (kundura)

and myrrh (vola)) for Chinese silk, or in obtaining local products such as

camphor (karpûra) from Sumatra, sandalwood (candana) from Timor or cloves (lavanga)

from the Moluccas.

Indians set out for

this Land of Gold from all round the subcontinent. Evidently, the shortest

journey was from Gauda (modem Bengal) and Kalinga: we know that Fa-Xian and

Yi-Jing took ship from Tamralipti. But the prevailing

wind across the Bay of Bengal from June to November is south-westerly, so the

most direct sailing was to be had from the southern shores, and this is the

area of all the ports noted by the Greeks .( Kamara, Pôdouké

and Sôpatma, `lying in a row', are quoted in the

first century AD Periplous of the Erythraean Sea ,ch. 60. Of these, the first two are presumably on the delta

of the Kaveri river and at Puducherry ,better known as Pondicherry.)

A handful of

inscriptions in Tamil, turning up in Sumatra and the Malay peninsula, confirm

this route. The ports of the western coast also had their share of departures

for the east: an old Gujarati proverb mentions the wealth of sailors back from Java.(From

a saying in the famous Goozerat,-"Who goes to

Java Never returns. If by chance he return, Then for two generations to live

upon, Money enough he brings back ..." Ras Mâlâ, ii.82)

More interesting for

us than the motivation of the Indian sâdhavah is how

they would have appeared to the receiving populations, known to the Indians as dvipântarah, `islanders'. These people, Burmese in the

east, AustroAsiatic in the south (Mon, Khmer, or

Cham), Malay in the islands, already used bronze, irrigated rice, domesticated

cattle and buffalo, and had ships and boats of their own. They would not have

been able to read or write, and would have presented themselves to the

local chiefs as visiting dignitaries, probably claiming royal connections back

across the ocean, and offering gifts, and perhaps medicines and charms. Winning

favour with local elites, some went on to take their

daughters in marriage, and thus sow the seeds of new dynasties.

What they

brought with them was literacy, and an ancient culture with a vast array of

rules (the sutras of the Dharmasâstras, or the

suttas of the Buddhist Tipitaka) for every occasion. There was a whole

mythology of making Agastya, Krishna, Rama and the Pandava

brothers into household names, as they have been ever since in South-East Asia.

There was the distinctive idea of the complementary roles of king and priest,

admittedly at sixes and sevens over which was ultimately the higher, but

clearly in a relationship of mutual support. This relationship could

underwrite, and make permanent, the legitimacy of rulers. And so the rulers

that the Indians met were happy to become their friends, business partners and

fathers-in-law. The new generation that sprang from the mixed marriages would

have been the first to receive a full Sanskrit education.

One characteristic

of this civilisation is that they brought with

them was a tendency to modify and customise the

alphabet. Just as there are now at least ten major scripts; Devanagari,

Gujarati, Panjabi, Bengali, Oriya in the north; Telugu, Kannada, Tamil,

Malayalam and Sinhalese in the south. There is another related alphabet, used

farther north for Tibetan. t Burmese, Lao, Thai, Khmer (Cambodian) on the

mainland; in the islands, Javanese, Balinese, Tagalog (in the Philippines),

Batak (in Sumatra) and Bugis (in Sulawesi), diffused all over the subcontinent

in Asoka's time.

There are another

nine that developed in South-East Asia, Indonesia and the Philippines,t all derived from Indian scripts, many through the Pallava

script of the south. The origin of this diversity lies in the variety of

writing materials available in different places, but the different styles

evidently came to be national icons. In the Cambodian pillars that carry rules

for monasteries, Sanskrit in Khmer script on one side is paralleled by Sanskrit

in a North Indian script on the other: perhaps there were North Indian devotees

as well as Khmers resident here.

This is just one of

many signs that there was heavy cultural traffic in both directions between

India and Indo-China during this period. Another example is given by the life

of Atßa, a monk born in Bengal in 982, who went on to

become one of the founders of Buddhism in Tibet in his sixties. He had spent

his student days in Sri Vijaya, in Sumatra.

Shwe Dagon in Burma, Borobodur in Java, Angkor Wat in Cambodia, as well as less

well-known magnificences in Pagan, Champa, Laos, Bali

and Sumatra, built over a millennium from about AD 500, all stemmed from these

seminal ideas. But at least in terms of architecture there is nothing now quite

like them here in India. We can only speculate that styles executed in

stone at Borobodur and Angkor Wat may echo the

architecture of wooden buildings long vanished from southern India.

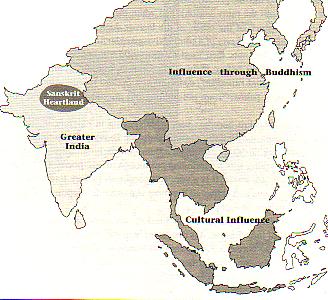

Nevertheless, this

roll-call of states and civilisations that took their

beginnings from this area reminds us how vast, how varied and how long lasting

this influence was, all the more remarkable because no military force seems to

have been applied anywhere to bring in the new, more organised,

Indian society. This contrasts sharply with the record of incursions from the

other developed civilisation to the north. Ever since

the first century AD, China had been putting constant pressure on the Annamite

kingdom of northern Vietnam, periodically invading it, and insisting on

recognition of China's emperor as its overlord.

The earliest

documented kingdom-the documentation is Chinese-was set on the lower

Mekong, in modem Cambodia and southern Vietnam, probably in the first century

AD. It is usually known as Funan, which is a Chinese version of its name. It

was really called, in Khmer, Bnam, `the mountain (the

same word is now pronounced Phnom, as in Phnom Penh), and its king as kurung bnam, a translation of Parvatabhiipala or Sailarâja:

bearing this title of `King of the Mountain', he would have established a cult

of the god Siva in a high place, so reconciling his legitimacy as an Indian

king with the native spirits of the land.

Funan's foundation

myth, read from a Sanskrit inscription in Champa, confirms this. A Brahman

named Kaundinya (derived from Kundin,

one of Siva's titles) received a javelin from another Brahman, a hero from the

Mahabharata named A.vattâman, and threw it to find

the right site for the city. He married a local princess named Soma, daughter

of the king of the Nigas, the many-headed water

cobras worshipped as protectors of Khmer riches.

Thereafter, major

Sanskrit-speaking states were set up all over South-East Asia, Sumatra and

Java. Java, Sumatra and Malaya are derived from Yava-dvipa,

`barley island'; samudra, `sea', and Malaya, actually

from a Dravidian word, malai, `a hill', in south India near Malabar. Cambodia (Kambuja) evokes Kambuja, a

kingdom in the Khyber pass area; but had a competing etymology as Kambuja, i.e. born of Kambu Svtyambhiiva,

a hermit who united with the celestial nymph Mera to found the race of Khmers .

Champa shares its name with the kingdom of the lower Ganges, but is probably

the local ethnonym Cham in Sanskrit form. The River Irrawaddy in Burma is named

for the Iravati, `having drinking water', the old name of the Ravi river in

Panjab.

Their names are

themselves in Sanskrit, and show either a sentimental link with other Indian

holy places far away, or an attempt to Indianise

local names. It is often difficult now to locate them exactly. In Malaya, Lankasuka, controlling one much-used overland route from

the Bay of Bengal to the Gulf of Siam, beside Tâmbralinga

(Ligor), Takkola (Takuapa) and Kâtaha (Kedah); in

Cham, the south of modem Vietnam, Amardvati (Dong-duong), Vijaya (Binh-dinh), Kauthara (Nha-trang), Pânduranga (Phanrang); in Java, Târumd (round Jakarta) and Kutardja

in the east; in Sumatra, Malâyu (Jambi), Sri Vijaya

(Palembang); in Burma, Sudhammavati (Thaton), Sriksetra (Prome or Thayekhettaya),

Hamsavati (Pegu), Sri Deva (Si Thep); and in the

region of modem Thailand Dvâravati, north of Bangkok.

Names of rulers too

are typically Sanskritic. Good examples are the more than thirty Cambodian

kings whose names end in -varman, `bastion', from

Jayavarman, who died in AD 514, to Srindrajayavarman,

1307-27, and the Majapahit kings of Indonesia from Rdjasa in 1222-7 to Suhitd,

1429-47. To an extent, this still continues, so Megawati Sukamoputri,

current president of Indonesia, has a name that translates as `Cloudy, Beneficent's Daughter'.

Also it was customary

to name a city after the king that founded it, thus for example, Sresthapura (literally `best of cities'), capital of

Cambodia, was named after its founder, King Sresthavarman

('best bastion'). It is likely also that Sri Vijaya, the dominant kingdom in

southern Sumatra, was named after a king named Vijaya, `Victorious'.

It is easy to

overlook what a major change the introduction of Sanskrit must have been for

the local peoples. Sanskrit, as a type of language, was fearsomely different

from the local languages, now classified as Burman, Austro-Asiatic and

Austronesian. Sanskrit is polysyllabic, and highly inflected, with a

complicated consonant system that is not averse to long clusters. Word order is

free. This language was being taken up by speakers of other languages where

words were short, often distinguished by tone, and made up of simple syllables

with single consonants at beginning and end. Inflections were simple or absent,

but word order was rigid. It was at least as radical a change as it would be to

bring Japanese in as an elite language where previously everyone had known only

English or Dutch. What a wrench it was can be seen in the mangled remains of

some of the Sanskrit names: Sriksetra came out as Thayekhettaya, Sri Deva as Si Thep.

For updates

click homepage here