By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Ella Thomas And The Medium

"I have to

record the saddest event which has ever occurred in my history, the death of my

father." Georgia gentlewoman Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas lamented in her

journal in 1864. "How calmly I write it and yet I look at the written

words and do not realise [sic] it yet. Occasionally

since his death the idea has obtained an entrance into my mind producing a wild

tumultuous grief to be succeeded by a quiet approaching to apathy." For

Thomas, the loss of Turner Clanton was "irreparable." She had visited

him often as he lay dying, hoping that somehow he would mend, but her hopes

were dashed.

Within a few days of

calling a family meeting, Clanton was dead, his lifeless body laid out on the

"old french bedstead" in the family's

sitting room. He had "summoned the energy of his iron will and met the dred [sic] King of Terrors with a calmness and composure

which approaches the sublime," Thomas wrote. "Perfectly conscious of

his impending doom no expression of fright or timidity passed from his

lips." 1

The emotional pain

Thomas felt following her father's passing lingered for months. According to ajournal entry from August 1864, her obsession with Turner

Clanton's spiritual condition prior to his death caused her to descend into a

"wild, unsettled, chaotic state of mind." Several years before,

troubled by her father's apparent marital infidelities, Thomas had openly

questioned his spiritual state in her journal.

Then, when it became

clear after his death that he had willed his own children-the sons and

daughters of slave women he had impregnated-to his white descendents,

she returned to the theme, complaining that the knowledge of her father's

grievous sins "tortured me as with the whip of Scorpions." Perhaps to

counteract the harsh effects of this discovery the Southern gentlewoman engaged

in a bit of escapist daydreaming. By fantasizing that he was not really

dead-but simply absent for a time-Thomas seemed to delay her emotional

acceptance of her father's passing. "I think of him as being alive at the

plantations-in the street," she confessed in her journal, "and cannot

think of him as lying in the cold and silent resting place in which he was placed

yesterday."2

Thomas's Methodist

upbringing no doubt gave her some mental tools for understanding and

interpreting her father's death, though she seemed to think that evangelical

Protestantism was woefully inadequate when it came to addressing the problem of

death. In the moment of her greatest spiritual need, Protestant Christianity

came up startlingly short. Her prayers, she wrote, ascended "no ... higher

than my head. "

And she complained of

being weighed down daily by "an incubus." Thomas lived like this for

several years, grappling with depression and loneliness, hoping somehow to

bring an end to the uncertainties that plagued her. More than anything else, Thomas

hoped for supernatural proof that her father's spirit continued to exist after

his earthly passing. She craved "to be sure, to have something

definite" to cling to in her grief, but felt that her own Methodist

pastor-a Mr. Scott-could not deliver the spiritual and emotional reassurance

she desired; he was both too aloof and too worldly to be an effective source of

consolation.3

The event that

finally provided Thomas with the psychic relief she desired came six years

later, in 1870, with a brief visit to a medium. The Georgia gentlewoman had

traveled to New York City with her mother, perhaps to escape family obligations

for a time. Visits to the opera. theater, and lecture hall seemed to fill her

need for relaxation.

There was, however, a

second reason for visiting the city--one she may have kept secret from even her

mother. Thoughts about the disposition of her father's spirit lingered, and

when she found out she would be traveling north, she resolved to fmd a medium there.

"You know my

Journal, for you do but represent in some degree an inner self, how I have

longed to know where [my father] is and what doing," Thomas wrote.

Thinking back to past conversations with her father, she claimed she had heard

him "say that if he thought he could communicate with my Grand Father or

Uncle that he would meet them at any hour of the night whenever they might

appoint. So too would I and the intention was formed and fully matured that I

should seek out a powerful medium when I visited New York.“4

The medium Thomas visited, apparently was the renowned Charles H. Foster who by

1865 was allegedly levitating himself in seances and materializing spirit hands

in broad daylight. According to his biographer, Foster was born to a

supernaturally-inclined family from Salem, Massachusetts; his mother alleged

that in addition to talking with her, her "spirit mends" often rocked

the infant Charles to sleep.s No doubt Foster wanted

people to believe that his unusual family pedigree made him a natural medium.

"I am simply endowed with a peculiar power," he later declared.6 Such

confidence must have been a valuable asset on his world tours. Billing himself

as the "greatest Spirit Medium in the world," Foster visited a good

number of Europe's royal courts, and performed before such monarchs as France's

Louis Napoleon, Italy's Victor Emmanuel, and Belgium's Leopold (who presented

him with a diamond ring). Not to be outdone,American

luminaries also found their way into Foster's seances; Presidents Abraham Lincoln

and Andrew Johnson, author Walt Whitman, and industrialist Jay Gould were all

spectators at his performances.7

The supposedly

otherworldly signs Foster offered Thomas as proof of her father's spiritual

existence made an indelible impression on her. She began to dabble with

spiritualism as early as 1857 and toyed with the esoteric practice of automatic

writing shortly after Turner Clanton's demise. She even wondered if the

muscle contractions she felt in her fingers while she wrote were actually

"some spiritual influence wishing to communicate with me." But it was

when her father's absence finally had time to sink in years later that the

spiritualist promise of human-spirit interaction took on.increased

importance for Thomas.8 "Never before had I been so near the confine of

the spiritual world as when I visited this mysterious man [Foster]," she

declared. But because Thomas left no written record of what she saw and heard

in the seance with Foster, we can only speculate about the marter.

The fact that Foster was a materialization medium, rather than a trance

speaker, strongly suggests that Thomas "saw" rather than simply

"heard" the "spirit" of her father. Indeed, Foster's

supposed talent for materializing spectral bodies leaves us with a fair amount

of certainty that he "caused" Turner Clanton (or at least some of his

ethereal limbs) to "appear." The language Thomas used to describe the

event also suggests that she had "seen" the ghost of her father: she

had some

reservations, she

wrote, about the way Foster had put her "in communication" with her

father. Was her supposed ability to talk with and see Turner Clanton, she

wondered, simply due to some "powerful legerdemain or witchcraft"? In

the end, though, it seems Foster's performance fully won Thomas over and

convinced her that her father's soul lived on after his death. "I had seen

and heard just enough," she confessed, "to make me wish to see Dr.

Foster again." Less than a year later, after numerous additional experiments

with occult ritual, Thomas made a second declaration about the alleged efficacy

of materialization, this time stating that it "comforts me more than any

other I know and confirms some ideas I have formed." Predictably, Thomas's

doubts occasionally resurfaced, but the "wild, chaotic state of mind"

she experienced immediately after her father's passing had dissipated, thanks

to the emotional consolation she drew from being able to "see" her

dead father.9

What made spirit

materialization so attractive to an educated and respectable middle-class

American such as Gertrude Thomas? Judging from the evidence she left in her

journal, materialization's appeal had at least something to do with its ability

to undo the personal catastrophe of a loved one's death by supposedly bridging

the chasm between this world and the afterlife in which so many Americans

sincerely believed.

Turner Clanton may

have been dead, but for his daughter his existence was not completely erased;

she wanted to believe that he lived on in a spirit world. Many like Thomas felt

that, thanks to public spiritualist mediums, the spirits of deceased mends and

relatives no longer were tom from the bosom of those who cared for them to be

permanently marooned across a biblical "gulf' that separated the mortal

and immortal realms. Rather, Thomas and other spiritualist believers assumed

that spirits were immediately accessible to humanity through the reputed

supernatural virtuosity of the spiritualist medium. Yet, it seems unlikely that

this was all there was to spirit materialization's appeal. After all, other

forms of mediumship, including trance speaking, also seemed to be effective at

communicating the message of immortality to the curious and the desperate. If

audiences were simply looking for consolation, they could surely find it in

other forms of spiritualist perfonnance.

Stories like Thomas's

suggest that it was the bluntly visual nature of spirit materialization-rather

than just its message of consolation-that was so effective in drawing

spectators into the materialization seance. Mediums who understood this, and

exploited the visual nature of materialization, seemed to fare quite well. In

fact, spirit materialization became such an appealing form of spiritualist

performance that by the 1860s and 1870s even once-popular trance mediums were

abandoning the trance lecture for materialization, sucked in by the hope that

it would "jump start" their flagging careers and bring them renewed

success. For these and other mediums, the move toward spirit materialization,

like similar decisions to take advantage of modem marketing techniques and

technologies, amounted to a strategic choice, driven in part by the growing

industrialization of visual entertainment in the years after the Civil War.

Indeed, the visual turn in the public seance was part and parcel of the mass

production of spectacle in the increasingly modernizing nineteenth-century

United States. In the end, materialization seemed to be able to do what trance

speaking could not-that is, produce alleged spirit bodies that spectators could

see and interact with on an intimate level.

Trance speaking may

have relied, at least in part, on visual stimuli-riamely

the visible body of the female medium-for its impact, but materialization took

visuality to a whole new level, enabling spectators to peer into the more

mysterious comers of the alleged spirit world.

It must be noted,

however, that the visual specificity of the spirit world mediums claimed to

offer eager spectators was the product of illusion, misdirection, and

manipulation. Materialization was theater, and techniques of theatrical stage

management-like the language of evangelical Protestantism, print technology,

and sex-became important tools of exploitation in the hands of shrewd public

mediums.

Spectators wanted

solid visual evidence of a real spirit world, and mediums were keen on

providing the illusion of it for them. As a result, those public mediums

carefully directed the materialization spectacle by deploying performers to

take on the role of spirits. In

many cases, the

performers (a group that sometimes included the mediums themselves) remained

silent while onstage almost as if they were trying to overemphasize the visual

evidence of embodied "spirits. Additionally, mediums also stage-managed

the visual spectacle of spirit materialization by manipulating systems of

theatrical lighting. By strictly regulating the presence of light in the

seance, they were able to control, at least in part, what spectators saw; with

darkness and light, they tricked the collective eye of the audience and gulled

spectators into thinking that they had actually caught a glimpse of the spirit

world.

Public mediums also

directed the visual spectacle of materialization through more mundane means.

They chose and arranged venues, for instance, to take full advantage of the

visual nature of the seance performance. For example, instead of performing

mostly in large auditoriums or theaters as trance lecturers tended to do,

materialization mediums sought out smaller, more intimate performance spaces

where they could better illuminate and illustrate the visually specific

afterlife they claimed to be able to show people. As a result, spectators and

"spectral beings" usually shared the performance space-some people

who attended materialization shows even claimed to be able to touch the

"spirits."

Materialization

mediums also allowed themselves to be bound or otherwise restrained as part of

the seance performance, thereby satisfying the empirical-mindedness of many seancegoers and "proving" that the visual

phenomena they produced were authentically supernatural.

Newspaper reports

from the late 1850s give us our first fleeting glimpses of the materialization

seance, which later accounts helped to flesh out. A correspondent writing in

1858 to the Banner of Light from Paris, Maine, claimed not only to see spirit

hands in the seances he attended, but "even the face and shoulders are

observed by all in the room, so plainly and clearly visible, that there can be

no mistake but the features presented are those of one who has passed from

earth-life.“10 By the 1860s and 1870s, this sort of phenomena had become an

entrenched part of spiritualist performance. Indeed, spiritual

materialization dramatically changed the status quo of occult performance by

bringing spectators into full visual and physical contact with supposed

spectral beings. In a typical materialization seance, the medium would cloister

himself or herself in a closet or box, supposedly become entranced, and

ostensibly produce the reembodied specters of the dead (or at least parts of

them). As visual symbols of familial love and inspiring proofs of the

indestructibility of the family unit, materialization seances became the final

word for many spectators on the persistence of family relationships beyond

death.

Over time, the power

of Victorian sentimental culture had primed spectators to seek out this kind of

"evidence" of a spirit world. The importance of familial interaction

in many spirit materialization shows points up the real desire of many Americans

to preserve the integrity of the family, even after death had broken it up.

They mourned, but as one historian of American culture has put it: "In

mourning, the bereaved proved they had not forgotten the dead." Indeed, to

the sentimentalist, "death was not powerful enough to sever the bonds of

domestic love" which were "stronger than those ties that bound

families together in life." Victorian Protestant culture encouraged the

valorization of survivors' feelings, while also memorializing the dead and

acknowledging the "spiritual possibilities" of a future world. Spirit

materialization fed off of this cultural trend. For many Americans,

materialization seances were proof positive of the ultimate indissolubility of

the family. 11

The materialization seance

was a radical departure from previous forms of spiritualist performance,

especially trance speaking, where the voice of the medium was the primary means

of convincing seancegoers of the existence of a

spirit world. The trance lecture segregated the mortal and immortal realms by

institutionalizing-even fetishizing-the intermediary role of the trance medium.

Rather than giving the public visual and physical access to the spirits, as

materialization mediums claimed to do, trance speaking severely limited contact

between the two worlds. Before the advent of spirit materialization, there was

little room for personal two-way interaction between spirits and mortals;

spectators interested in forming a relationship with the spirits had to be

satisfied with what came from the trance medium's mouth, or worse yet, with

what could be gleaned from such non-verbal phenomena as table-tipping and

automatic writing.

Seeing the writing on

the wall, some early mediums abandoned trance speaking for spirit

materialization. Even well-known trance mediums like Cora Hatch Tappan (by the

1870s she had remarried and had adopted a new last name) eventually jettisoned

the oral tradition of the trance lecture for materialization. Tappan, however,

seemed more comfortable producing "spectral" flowers than

"spirit" bodies; according to one observer who attended one of her

seances in 1875, the lilies she materialized "were each time clearly

visible; I could distinguish the leaves and the petals." Other former

trance mediums like Mrs. J. H. Conant went a step further, and allegedly spoke

"face to face with the invisibles." Trance speaking was gradually

moving into its twilight days, and a new visual regime was taking its place. 12

As spiritualism

matured, the aurality of trance speaking seemed to run squarely against the

grain of Enlightenment ocularcentrism. "The dawn

of the modem era," historian Martin Jay writes, "was accompanied by

the vigorous privileging of vision.

From the curious,

observant scientist to the exhibitionist, self-displaying courtier from the

private reader of printed books to the painter of perspectival landscapes ...

modem men and women opened their eyes and beheld a world unveiled to their

eager gaze."

Thus, Jay observes,

we get Francis Bacon's comment, "I admit nothing but on the faith of my

eyes," and Scotsman Thomas Reid's, "Of all the faculties called the

five senses, sight is without doubt the noblest" 13 Other historians have tried

to modify, if not overturn, this metanarrative of modem hypervisuality

by positing a "more diffuse and heterogeneous" modem

"sensorium," with orality and the act oflistening

existing at least on the same plane as vision. As Leigh Schmidt has argued,

modem "understandings of the senses were inevitably much more fluid and

sophisticated than any emphasis on vision's hegemony suggests.“14 Still, if we

are to believe the evidence, vision seemed to play greater and greater role in

connecting Americans to their world as the nineteenth century progressed, a

reality materialization mediums and the actors who worked with them vigorously

exploited.

Thousands of

"spirits" materialized each year in seances around the nation, thanks

to human performers who played them by donning wigs, masks, and other tools of

disguise. The job of these performers was to convince spectators of the

existence of a visually-specific spirit world. No sooner had the

materialization seance been born in the late 1850s, than this new style of

performance grew into what can only be described as a cottage industry for

mediums. What is more, materialization-which had been built on intentional and

calculated deception--proved to be quite popular. However, the richly

descriptive firsthand accounts of materialization seances left by people like

Henry Steel Olcott, Mary Dana Shindler, Thomas Nichols, and Paschal Beverly

Randolph unfortunately do not tell us who played the spirits in the nation's

spirit materialization performances; not surprisingly, neither mediums nor

their biographers described-or even alluded to-their deceptions. This leaves

modem historians in a tight spot. Without any written acknowledgment from

mediums or their allies concerning the séance "backstage," not only

are we dependent on guesswork and public expose accounts to figure out just how

mediums and actors were able to trick audiences, but we cannot even know for

certain what a typical "materialization troupe"looked

like. We can surmise,though, that most

materialization companies were rather small, as it is unlikely a medium would

have needed more than a few players to pull off a seance. (The small size of

the seance company would not have been unusual. The standard traveling acting

company from the same period also tended to be small; many were single-family

troupes.)

Sometimes mediums

performed alone, dressing up as "spirits" themselves, as in the case

of Henry Gordon.15

But if we cannot know

for certain the dimensions of the materialization séance troupe, we can be sure

that in spirit materialization performances mortals masqueraded as

spirits-thanks, in part, to those seance performers who ended up being exposed

as frauds. There were always people in an audience whose dream it was to unmask

a "spirit." Numerous seancegoers echoed the

sentiment of one shrewd observer that he could easily see through a medium's

disguise and detect "the features, the height and the voice of the

medium.“16 In the case of one pitiful female American medium, her inability to

trick the audience by acting the part of a convincing "spirit" led

directly to her unmasking. According to an article published in the Spiritual

Scientist, this "little American women, who is said to be a good

medium" had traveled to England expecting to cash in on the British market

for materialized spirits. Her controlling "spirit," the newspaper

read, was not one of the high-profile "specters" always in demand in

seances around the country, but rather "a plain German baron"-an

apparent unknown on the materialization seance circuit.17

One evening, at one

of the American medium's performances, the nondescript "baron"

appeared, no doubt prepared to deliver an important message from the

"spirit world." We can almost imagine him scanning the audience for

an eager spectator to engage. The "baron," however, was out of luck,

for when he stepped out in front of the audience the "sitters"

immediately recognized that there was something terribly wrong with his

appearance: "one comer of his moustache," it seems, had "turned

down towards the left shoulder, and the other side turned up in the direction

of the right eye." The discomfort that likely rippled through the audience

must have been near palpable, broken only by the voice of a single seancegoer who screwed up enough courage to point out the

cockeyed moustache. "Is there not something wrong about that

moustache?" asked the plucky spectator. "It is all on one side."

According to the Spiritual Scientist, "it was generally admitted that such

was the case, and notwithstanding the theory of one lady that 'perhaps he died

so,' the gentleman then investigating seized both hands of the baron and the

medium stood exposed in her simulations." We do not know what, if

anything, happened to the "little American woman," but we can guess

that she was carted off to jail or otherwise punished for defrauding the

public.18

Other players were

more successful at convincing seancegoers that they

were materialized spirits. These were the men and women who kept spectators

coming back again and again to the materialization show. Not surprisingly,

however, they too were dogged by allegations of fraud. More than one observer

noted that once materialization seances became widespread, "and deep

interest was elicited in the minds of the mass, a host of mountebanks and

pretenders seized upon [such performances] as a means of getting into notice,

or of acquiring a livelihood." A critic wrote in Tiffany's Monthly, a

magazine dedicated to the investigation of the "science of the mind,"

that the most credulous elements of the seance audience trusted these

mediums, even as the latter "continued practicing their impositions while

it promised them remuneration, or until they were detected and exposed."

"Every class of mediumship," the contributor to Tiffany's concluded,

"is counterfeited by them, and they hesitate not to swindle, deftaud : and cheat in the name of spirits." 19 Still,

actors continued to perform in materialization seances, undoubtedly driven by

the financial rewards that came with being a part of show business. If the

figure cited in part 1 as an average weekly take for a public seance that is

$210-were divided evenly between four people (say the medium, the manager,and two actors) each person could expect to make a

little more than $50 a week. (It should be remembered that the typical

theatrical supporting player only made between $15 and $40 for a week's work.)

An increase in the number of performances per week would of course have bumped

up their take. 20

What did the players

perform for this kind of money? It is hard to describe an average

materialization seance, simply because there were so many variations on what

people identified as "spirit materialization." In some cases, actors

or mediums dressed up like spirits and rang bells or played musical instruments

while staying safely ensconced inside the spirit cabinet or box, only

occasionally showing their faces at a hole or screen in the cabinet door. In

other materialization seances, performers actually stuck parts of their bodies

out of holes in the cabinet. A correspondent for the Banner of Light once

claimed, for example, that he saw hands and arms "in the aperture of the

cabinet, three hands often visible at the same time." This type of visual

trick was an especially prominent feature in seances performed by the

Davenports. On one occasion, wrote an observer, the medium brothers had no

sooner been tied up than a "human hand appeared at the window."

Another spectator also recalled seeing what he believed were spirit hands

protruding from the Davenports' cabinet. "They move very rapidly," he

wrote, "and appear to be of different sizes. Sometimes a hand and arm is

thrust out almost the entire length.“21

The type of

materialization that seemed to attract the most public interest, however, was

the manifestation of fully formed "spirit" bodies on the seance

stage. Full form materializations were highly anticipated events at public

seances, no doubt because seancegoers saw them as the

best evidence one could hope for of a real spirit world. Of course, full-form

appearances also gave actors masquerading as spirits their best opportunity for

using whatever theatrical training they had acquired to win over audiences. The

evidence seems to suggest that their performances were often successful.

Spectators were awed

when they came face-to-face with a supposed spirit in its full bodied form; the

language they used to describe their wonder reached into the superlative

register. Regarding one medium, an amazed seancegoers

wrote that "Mr. Church seems to me to be a medium of most astonishing

powers. Through his personal magnetism spirits are able to materialize

themselves with the utmost perfection, so as to speak in loud and perfectly

audible voices, untie the most complicated knots, handle those present in a

very forceful style," and "perform every variety of physical

feats." The "spirit" Church materialized most often was "an

Indian spirit" called Ne-mau-kee, a virtual giant by the writer's measure.

"I have distinctly seen his figure," stated the observer, "as he

stood between me and the dim light of a partially darkened window." He had

a "hoarse, whispering voice" and when he danced, the force of his

movement shook "the whole house." Other "spirits" also

appeared under Church's direction, often "manifest[ing]

themselves two and three at a time, in different parts of the room.“22

Sometimes the

"spirits" that appeared in materializations seances were assumed to

be the ghosts of dead loved ones, though it is important to note that spirit

materialization offered more than just visual "evidence" of the

persistence of dead family members. At times, materialization mediums and

seance performers painted on a broader spiritual canvas, offering spectators

the illusion of a diverse, vibrant spirit world peopled by more than just the

relatives or friends of seancegoers. The spirits that

William and Horatio Eddy supposedly materialized for Mary Dana Shindler at

their Vermont homestead, for instance, ran the religious, ethnic, and racial

gamut, from an Irish washerwoman, to a gaggle of New Yorkers, a few Shakers,

and a smattering of American Indians. The apparent lesson mediums were trying

to convey in such a seance was clear: even the spirits of ordinary people could

add value, however slight, to the relationship between the mortal and

immortal worlds.23 But, if the significance of materializing ordinary "spirits"seemed obvious to spiritualists, what ought we

to make of the supposed appearance of more illustrious "spirits,"

like Jesus, Benjamin Franklin, the Marquis de Lafayette, and, of course, George

Washington? Such ostensible visits became events of particular wonder for those

who witnessed the 'materializations, and no doubt lent credibility to the

medium's illusion. Spiritualist and former New York State Supreme Court justice

John Worth Edmonds recounted witnessing an appearance by Washington's

"spirit," using language that well reflected the awe he felt at

seeing what he imagined was the dead President. Arrayed in a "pale-blue...

transparent" robe that was "ever moving like living flame," the

noble "spirit" Washington demonstrated a "great firmness as ifhe could stand unmoved amid a conflict of worlds."

Explaining that he had returned to earth to restore the United States to its

founding values, Washington bemoaned the nation's turn toward "oppression

and selfishness.“24

For mediums, the idea

of linking themselves to Washington proved to be a smart marketing move. The

former President was, according to historian Robert Johannsen,

nineteenth-century America's "most revered personage, its greatest

hero." And over the years, the former President's mythic significance in

the American national consciousness continued to grow exponentially, thanks in

part to the "cult of Washington" created by artists, writers, and

statesmen who had made the general the focus of their culturallabor.25

Perhaps the most

intriguing brand of spirit materialization, however, had to be what we might

call the "silent seance." In this kind of performance, the actors who

played the spirit beings did not speak. Like other forms of spirit

materialization, silent seances were manipulations of reality-the human

performers playing the spirits certainly had the ability to talk, but they

declined to do so in order to give greater credence to the materialization

seance's visual "evidence." Of course, we could also explain a

performer's choice to keep quiet onstage as simply motivated by a desire to

avoid detection, especially by anyone who might recognize his voice. But so

many "spirits" talked in seances that this explanation seems

unlikely. Besides, actors playing spirit beings could have easily modulated

their voices to keep nom being identified, or mediums could have explained away

incongruous voices by arguing that the way people talk changes when they

"cross to the other side." Many spectators were quite willing to believe

peculiar explanations regarding seance phenomena. Indeed, it seems that the

choice to stay silent was as much about reinforcing the visual power of

materialization as it was about avoiding detection. By refusing to talk, the

performers that played spirit beings on the seance stage, whether they were

mediums or their accomplices, dramatically foregrounded the visual evidence of

life after death that spirit materialization supposedly provided. When examined

from this perspective, the materialization seance registers as visual spectacle

of the first order.

Of the sources that

describe the silent "spirits" in materialization performances,the

narratives describing the Eddy seances left by Henry Olcott and Mary Shindler

are perhaps the most revealing. (Like Olcott, Shindler had made the long

pilgrimage to Chittenden just to see the Eddys.) In his writing, Olcott

consistently marked the existence of silent "spirits," the most

captivating of which, he argued, were a pair of Indian characters known as Santum (identified as a "Winnebago spirit") and Honto (whose supposed tribal origins Olcott never made

clear). According to Olcott's detailed

description of the

two "spirits," the physical appearance of "Santum"

was "calculated to excite surprise"; at a little more than six feet

tall, argued Olcott, he truly was a being of "stature and bulk." His

clothing, made of ftinged buckskin and

"ornamented with stripes of embroidery," the reporter remarked, set

him apart as a person of distinction, as did the single feather he wore in his

hair?6 The performer who played Honto, on the other

hand, was less imposing physically, measuring a little more than five feet

tall. "Young, dark complexioned, of marked Indian features, lithe and

springy in movement ... and full of inquisitiveness," she was a favorite

among spectators. Unlike the actor who masqueraded as Santum,

the person who played Honto dressed in bright, airy

clothes, with the exception of her deerskin leggings, and wore her hair

"braided in a single rope down her back." She was also known to smoke

an occasional pipe and knit scarves as part of her performance.27 We do not know

who played either "spirit," but a rare unguarded, comment by Olcott

gives us a"Clue as to who might have been

dressing up as Honto. The first few times he saw her,

the reporter confessed, he "fanc[ied] her the same as William [Eddy] in height and bulk.“28

Both characters

stayed quiet onstage, communicating only through body language and hand

signals. The person that played Santum was

particularly taciturn, and Olcott and Shindler each acknowledged "Honto's" persistent silence. Shindler remarked,

perhaps somewhat disappointedly, that had the alleged female spirit been

"able to speak... she would delight the audience much more, and create

quite a furore [sic]," while Olcott remembered

seeing the native "spirit'''' regularly clap her hands in order to

communicate.29

In his account of a

series of "moonlight materializations" that occurred at a place lalown as "Honto's

cave," Olcott illustrated just how a silent seance worked. According to

the reporter, the Eddys had remade the cave (which Olcott surmised had carried

some spiritual or cultural significance for local native bands) into a

makeshift amphitheater,replete with wooden benches, a

rickety stage fashioned from rough joists and floorboards, shawl curtains, and

a backing of green boughs.30 It was here that the character of Santu made his

quiet appearance in the craggy rocks high above the audience, his "giant

spirit form" noiselessly appearing "in bold relief against the

moonlit sky." (If an eagle-eyed spectator had not pointed him out, he may have

gone unseen.) Other "spirits" also appeared and performed an odd sort

of pantomime around the cave entrance. One "Indian" emerged out of

the makeshift cabinet, "stepped into the stream, and, stooping, made the

motion of drinking some water from his hand" (emphasis mine). "Honto" also materialized and "made as if drinking

from the brook" (emphasis mine).

Throughout the

performance, wrote Olcott, the "stillness of the forest" was

"broken only by the noise" of a nearby brook, chirping insects, and

the "rustle of leaves as they stirred in the warm wind of spring.“31

Other seances also

revolved around voiceless spirits. A materialization performance by a Mr.

Eglinton featured a male "spirit" with a dark beard and balding head

who simply bowed or shook his head in response to seancegoers'

questions. Before taking up with the Eddys, Mary Shindler attended a number of

materialization seances in Boston performed by a female medium with the last

name of Boothby, who also materialized silent spirits. Like her Vermont

counterparts, Boothby invoked "spirit" bodies, commanding them to

appear in her seance performances. Shindler claimed that while she was in

Boston, Boothby materialized a host of spirit beings-including the alleged

ghost of her husband-but only a few spoke to her; ironically, her supposedly

dead spouse was one of them that stayed quieen.

The silent nature of

these and similar performances meant that spectators had few,if

any, aural cues to guide their thinking about the seance. Instead, vision was

the dominant sense used by mediums in these performances. It is telling that

Olcott reported that the eyes of the audience at the Eddys' night-time

materializations were "riveted" on Santum

and his fellow Indian "spirits." People had to use their eyes to

interpret what they saw. Indeed, the existence of this hypervisual

sort of materialization seance points up the fact that at least some mediums

and actors played directly to people's sense of

vision in order to emphasize, to a great degree, the specific visual

"details" of life after death that many seancegoers

craved.3

Mediums carefully

controlled the light that was allowed in the seance room.Many

(if not most) written accounts of spirit materialization emphasize the fact

that when spectators "saw" spirits on the materialization stage, they

were often sitting in a dark room, peering through the thick gloom and

straining their eyes to catch a glimpse of someone they recognized.

Materialization mediums had put them at a distinct disadvantage but mediums

knew full well that their ability to manipulate light was absolutely essential

to the success of the materialization illusion. Drawing inspiration from the

market and entertainment cultures of the post-Civil War end they were using

light and darkness to fashion a fantasy world in which spirits supposedly mixed

with mortals. The management of light, then, became a vital element of the

medium's stagecraft.

Coming out of the

Civil War a changed country~ the United States was just beginning to experience

the first phase of a sort of economic and cultural "empire of the eye.“34

Historians of consumer culture have generally pegged this fundamental change to

a later periority namely the 1880s- the 1890s, and

the first few decades of the twentieth century. They point out that

advertising~ with its attention to "the visual," as well as the

ocular "dreamworld" of the urban department store-built on innovative

strategies for exploiting light, glass, and color-was an artifact of this later

era.35 There were, however, earlier precedents for this intensely visual regime

in early-nineteenth-century commercial culture. Consider the use of signs.

Colorful commercial signs, many of them of taller and wider than anything a

regular American had ever seen before, achieved a commanding presence in the

antebellum city, in part because, as one historian has noted, "they

perpetually address[ ed] their readers without having to be picked up or

opened." Even the less imposing signs that hung outside small shops were

useful in engaging the sight of people on the street, and were explicitly

designed to stop pedestrians and lure them inside with their colorful

attractiveness. Both sign styles helped engender a greater visual consciousness

in their viewers.36

In addition to signs,

there were also three-dimensional commercial displays in stores and small shop

windows that especially relied on the manipulation of light. Both in the United

States and Europe, the shop window display became a veritable work of visual

art where glass, mirrors, and lights were used to create fantastical feasts for

the eye. As early as the eighteenth century, observers were recording their

response to these displays. The great English writer Daniel Defoe, for example,

left a very detailed description of one such display that emphasized the

strategic placement of various types of glass and candlesticks; no doubt these

elements were meant to reflect and refract light in imaginative ways. Gas

lamps, which became available on a wide scale after 1800, made the strategic

use of light even more conventional and ubiquitous, in part because gas and the

light it gave off could be much more easily managed than kerosene or a

candlewick. 37

Managers of the

late-nineteenth-century entertainment industry also deployed light in strategic

ways in order to emphasize and support visual spectacle in the nation's

performance spaces. Replacing candles, gas lighting in American theaters had

been around since 1816 when gas pipes were first installed at Philadelphia's

Chestnut Street Theater, though it took years for gas to become omnipresent in

the nation's theaters.

Once gaslight caught

on with the majority of theater owners, however, the increased brightness it

brought to performance spaces, as well as its flexibility (it could be

regulated simply by turning a knob) radically changed the look of stage

performances by nudging "acting and scenery toward greater

naturalness." (Brighter light meant actors could curb their flamboyant

stage action, while stage designers were free to use more natural colors in

their painted sets and backdrops.) Depending on the desired mood of a scene,

gas lighting could be faded in and out; this technique was especially useful

for "dissolving" between scenes. Gas could even be used to produce

special effects, such as simulated fires, though other methods of lighting were

used to generate some of the most spectacular effects. (The brilliant white

light created by burning lime or calcium was used to simulate twilight,

rippling water, moonlight, and clouds. Entertainers could also focus lime or

calcium light with lenses and use it to spotlight actors and other

performers.38

Electricity, of course,

changed things further. In addition to solving the potentially deadly threat of

leaking and exploding gas, Thomas Edison's 1879 discovery of the

incandescent bulb dramatically increased entertainers' power over lighting. Now

a simple flick of a switch was all that was needed to trigger the lights. The

advent of electricity even created some cultural space for the invention of a

new American professional: the theatrical "lighting designer." The

first such designer-James Steele MacKaye-envisioned using light to reproduce

"nature's moods and colors," and eventually invented a variety of

technical mechanisms both for projecting moving images across theatrical

backdrops and for "painting" stages with colors that reflected

"scenic moods." David Belasco, who followed MacKaye into lighting

design, "regarded light as the unifying principle which would link the

actor and the stage setting in an artistic entity." Ironically, though, as

electric light was "transforming the stage," writes Wolfgang

Schivelbusch, "an equally significant metamorphosis was under way in the

other half of the theater," as theatrical managers soon realized that a

brightly lit stage coupled with a dark auditorium greatly enhanced people's

ability to see the performers. Darkness in the gallery also forced spectators

to concentrate on the action on stage.39

In the case of the

materialization seance, darkness was the standard; there was no real

bifurcation of the performance space, with one end of the room staying fully

lit while the other was dimmed. Instead, mediums and their managers kept the

entire séance venue dark or nearly dark, enveloped in what one seancegoer appropriately labeled the "Cimmerian

gloom.“40 More than one seancegoer reported that

materialization performances--or at least the ones they attended-"always

take place in the dark.“41

What little light

mediums let into the seance room was carefully controlled to provide just

enough illumination to allow spectators to see vague forms, but it could not

have been enough light to help audiences identify the "spirits" with

much accuracy. The Eddy siblings, for instance, permitted a single light in

their seance room, but positioned it well behind the audience at a distance of

almost thirty feet from the materialization platform.

(The room was only

thirty-seven feet long.) The use of such tactics, however, did not stop some

spectators like Henry Olcott from adamantly claiming that they could see

everything perfectly, even in the dark. Olcott declared that even in a darkened

room he could "distinguish the salient points between" materialized

spirits and thus tell them apart. 42

In account after

account, darkness is portrayed as a necessary precursor to the high emotional

drama of materialization, which may explain why so many written records of

materialization performance account for a ritual "dousing of the seance

lights."

Consider the story,

related in an 1877 article in the American Spiritual Magazine, of a Vermont

judge and his allegedly reembodied spirit wife who had "returned" to

earth in order to renew her marriage vows. Attended by a crowd of "some twenty

persons, ladies and gentlemen," the seance was led by Ann Stewart, a

medium whose "phase of power," the newspaper claimed, "consists

principally in materializations of disembodied spirits."

When Stewart finally

entered the spirit cabinet, everything went quiet and the lights were

"turned down." Only then was the stage for materialization set.

Twenty minutes ticked by, according to the newspaper report, before "an

angelic figure arrayed in complete bridal costume of snow white texture"

stepped out of Stewart's cabinet. "Indescribably beautiful" and

covered with a "veil, which appeared like a fleecy vapor, encircled her

brow, and being caught at the temples, fell in graceful folds" that

"almost envelop[ed] her entire form," the assumed apparition

"walked softly out upon the rostrum," in front of the audience. The

judge, the newspaper alleged, "at once recognized the materialization as

that of his departed wife." Without skipping a beat, he "approached

her with affectionate greeting... placed within her gloved hand a bouquet of

rare flowers" and "imprinted upon her lips a fervent kiss." A

local magistrate stepped forward, and with very little formality, performed a

wedding ceremony in the name of the "great Overruling power.“43

A similar account by

Texas spiritualist Mary Dana Shindler also shows how the onset of darkness in

the seance served as the necessary spark for making contact with the

"spirits." According to Shindler, an "old, portly, and venerable

looking gentleman" had come to the Eddys' Vermont homestead hoping to see

the spirit of his dead spouse, but he had failed. Emotionally spent, the

"sad and solitary" man made preparations to

return home, though he seems to have found just enough energy to attend one

more performance. It was there, in the near dark of the seance, that the old

gentleman finally seems to have experienced what he had wanted so

desperately to see and feel. The light had hardly been turned down, wrote

Shindler, before "we heard the sound of kisses and distinct pats, as of some one fondly caressing another. 'Is it you, my darling?'

we heard from a manly voice, broken by sobs. The whispering answer could not be

heard, save by the weeping husband, but fond kisses were showered upon his

face, head, and hands." When the seance was finally over, Shindler and her

fellow spectators crowded around the man, who claimed that he "was

satisfied; I know I have been caressed, kissed, and spoken to by my angel

wife.“44

It is highly ironic

that performances like these, purporting to provide spectators with visual

evidence of a spirit world, were conducted in the dark. Darkness, after all,

generally serves to impair rather than improve one's vision. So why was the

ritual dimming of the lights such an important part of what some observers

began calling the "dark seance"? The simplest answer to this question

is that darkness provided cover for mediums and their confederates

to move about in the seance without much fear of being discovered. The

transition from light to darkness in the seance room, wrote one astute observer

of materialization, dulled the senses until "every sense, but that of

hearing, is gone." Darkening the seance room allowed mediums to "play

any trick upon the audience with impunity, because no proof can be given

against the performer, unless he is known to have moved." Perhaps more

important, though, is the less obvious answer: that the visual ambiguity

created by the dark seance actually seemed, in some counterintuitive way, to

breed belief. As the examples above demonstrate, there were people who wanted

so much to believe in the authenticity of seance phenomena that they would

project ontoany "spirit"-even one who was

literally shrouded in darkness and could barely be detected-the characteristics

and personality of a deceased loved one. A spectator who could not fully see a

"specter" was free to believe anything she wanted to about it, even

that the "spirit" was the shade of a long-lost child, sibling, parent,

or friend. A darkened room left spectators exposed to the intense power of

suggestion, coming not only from the medium, but from their own minds. In the

dark, members of the audience could give full rein to their own delicate

emotions and imaginations regarding the spirit world.45

Another story, this

one from Henry Steel Olcott's People from the Other World, bears this

conclusion out. According to Olcott, a German music teacher named Max Lenzberg

had traveled, along with his wife and daughter, to Chittenden, Vermont, from

Hartford, Connecticut, in the hopes of convincing Horatio and William Eddy to

contact his two dead children. Lenzberg, who played

the flute, had spent the evening of September 17, 1874, making music for the

seance, a talent that had earned him a prime spot in "advance of the front

row of spectators and within a few feet of the [spirit] cabinet." Things

had gone remarkably well for the mediums that night; eight "spirits"

had appeared before the seance finally began to wind down. Then, in a dramatic

coda to the performance, the cabinet's curtain "was again drawn

aside," and, according to Olcott, the audience "saw standing in the

threshold, two children. One was a baby of about one year, and the other a

child of twelve or thirteen." Behind them stood the figure of an old

woman, who stooped to support the youngest "spirit" child. Lenzberg, from his prime spot in the front row, was the

first to see the supposed ghosts, but it was his wife who seemed genuinely

moved by the event, and who made the mental leap to claim the supposedly spirit

children as hers. As Olcott put it, "Mrs. Lenzberg,

with a mother's instinct, recognized her departed little ones, and with tender

pathos, eagerly asked in German if they were not hers." According to the

author, "several loud responsive raps" convinced her that they were

indeed the spirits of her deceased children.46

What is baffling

about this account is that anyone could claim to recognize the forms that

appeared onstage. The Lenzbergsi "spirit

children" refused to expose themselves to what little light penetrated the

chamber, choosing instead to hover at "the edge of the black shadows of

the cabinet." How could the Lenzbergs have

professed to identify, with any certainty, the dark silhouettes that emerged

from the spirit cabinet.47

The answer to this

question lies in the fact that they were deeply invested in the project of

materialization; they, like thousands of other Americans, desperately wanted to

be able to interact with the spirits of their dead loved ones. With this in

mind, it is understandable how they could have bought into the idea that the

mortal and immortal parts of their family had been momentarily reunited. Yet,

at least one member of the family expressed some doubt. Olcott suggests that

Lena, the Lenzbergs' surviving daughter, seemed to

balk at what she saw. The darkness of the room forced her to "strain her

eyes" and "peer" closely at the "spirits," and

at first she hesitated about drawing any conclusions about what, she saw. In the

end, however, the suggestion that the "spirits" were her disembodied

siblings finally seemed to win her over. Like her mother, she too inquired in

German if the forms she was seeing were her siblings, and when the

"spirits" again rapped in the affirmative, she jettisoned the last

vestiges of her skepticism. According to Olcott, "the spirit-forms danced

and waved their arms as if in glee at the re-union."47

In addition to

deploying darkness to convince audiences that they had the power to materialize

ghosts, public mediums, much like other performers, also used light to create

sophisticated special effects (at least for that time) that appealed to curious

spectators. Phosphorus oil was an especially handy way for materialization

mediums to highlight the movements of musical instruments carried around a

darkened room by alleged disembodied spirits. A trumpet or guitar smeared with

glowing oil, and then suspended from the ceiling using thin cable or

string-especially within the context of a dark room-could easily create the

illusion of instruments floating through the air. Such tactics relied heavily

on the disorienting nature of darkness and the proclivity for humans' eyes to

play tricks on them. "If there was but a glimmer of light to be seen"

reflecting off the phosphorus, wrote the author of an expose of the Davenport

Brothers, "some judgment might be formed as to the reality of [the instruments']

flight." Without "any mark to go by in the dark," if the

instruments with their "luminous spots" are "held

overhead," he continued, "they seem hovering near the ceiling."

That this type of visual effect at least convinced some spectators of the

existence of a spirit realm is evident in a joint statement made by an audience

committee from Cleveland. In their words, the seance they had seen the

Davenports perform had "closed with a display of lights" that passed

from a "trumpet at an elevation of ten feet at least from the floor,"

and then zig zagged "from one side of the room to the other. .. with the

velocity of lightning."

According to the

committee, the phenomena they saw "were no other than what they claimed to

be, namely; spiritual manifestations.“48

In addition to

creating elaborate special effects with light in order to convince spectators

of the existence of a spirit world, many mediums also used light to disorient seancegoers. By ordering the house lights to be turned on

and off, sometimes several times over the duration of a seance, mediums created

abrupt shifts in light levels that effectively-if only temporarily-blinded

their audiences. In the words of the author of the Davenport expose quoted

above, "it is well known that after a person has been in the dark a short

time, and a light brought suddenly to bear on him, his eyes are always dazzled

so as to prevent him using them immediately." At the same Cleveland séance

where spectators said they had seen supematurallights

shooting from a flying trumpet, the medium was constantly ordering the lights

to be turned on and off, under the guise of proving the authenticity of his

seance performance. First the lights were extinguished, but when the

"spirits" started to become active, the lights were ordered back on

again to reveal that the mediums were still in their seats (rather than roaming

the seance room engaging in trickery). The lights were again turned off, but

within minutes someone speaking into a trumpet with a "sharp quick

voice" ordered them on again. "In an instant" wrote the

Cleveland committee, a lantern was ignited "and there in the center of the

room covered with several thicknesses of sheets, stood what purported to be a

human form almost three and a half feet in height, in a bending posture, a hat

on its head, and holding the trumpet apparently to its mouth." The

audience "gazed at the figure intently for about four seconds"-firmly

believing it was a materialized spirit-until the same voice "spoke

distinctly, 'put out the light.' As the light was turned off the covering [of

sheets] was seen to fall from the spirit." By this time, the people in the

audience were probably blinking furiously, dazed by the fast-paced triggering

and squelching of the lights and wondering if they would again regain their

night vision. Their eyes seem to have had a hard time adjusting to the rapid

changes in the room's lighting for they admitted "there was not sufficient

light to discern" the supposed spirit's "features distinctly."49

Paradoxically, the

practice of flashing the audience with rapid bursts of light and darkness

actually seems to have won at least some observers over to a belief in

spiritualism. The power of this tactic can be found in an account of a

materialization seance from 1857. According to those who recounted this story,

the seance lights had been dimmed and the medium was seated in his cabinet,

where supposed spirits quickly tied his hands and "called for a

light." He was found, wrote the authors of the account, "tied in a

manner to preclude the possibility of a doubt as to his ability to untie

himself."

The lights were again

put out, but a moment later the medium called again for the room to be

illuminated in order to show that the "spirits" had mysteriously been

able to remove his coat while keeping his hands securely tied. It appears from

the written account that the lights were doused a third time, and a third time

the "spirits" acted by replacing the medium's coat, again while

keeping his hands bound. In this seance, the dousing and igniting of the lights

seemed to have served as a sort of dramatic device that opened and closed the perfonnance's most important scenes, leading spectators to

accept it as a more or less functional element of the materialization perfonnance. Rather than being put off by it, then, the

audience claimed that the seance "completely upset the last remains of our

scepticism [sic]." "We do not pretend to be

able to account for these things," they continued, "we only know that

our senses did not deceive us. "50

By the 1860s and

1870s, the topic of light and darkness in the seance had risen to become a key

point of contention in the public debate over spirit materialization.

Opinions ranged from

absolute belief in dark seance materialization to utter rejection of it. After

witnessing a few examples of dark seance phenomena, one observer expressed his

unabashed faith in its persuasive power, declaring that it would convince "many

of the real presence of disembodied intelligences. I frankly confess, for

myself, that I was made truly happy, in having every stumbling-block

removed."sl Predictably, many non -spiritualists

argued the opposite: that the dark seance was nothing more than an instrument

of bald deception. A writer connected with a committee of New York

businessmen involved in ferreting out fraud among mediums publicly stated that

dark seances were simply the work of "impostors," and were the

"results of trick and illusion."

Materialization

mediums liked darkness because it allowed them to exploit the"imagination"

of spectators "apt to be abnormally excited in the dark.“52 .

A number of believing

spiritualists also attacked the near ubiquitous use of darkness in

materialization seances, arguing that dark seances were a terrible distraction

from so-called superior manifestations of spirit power, and seemed to leave

spiritualism open to attack from the outside. What, they queried, could be the

reason for keeping seances dark? According to one spiritualist critic of dark

seances, the absence of light in seance performances had "been...

injurious to the spread of public confidence in the verity of spirit-life and

communication, and had made "materialization exhibitions focus points of

trickery. The power of the spirit world, the spiritualist continued,“strong enough to produce all needed phenomena in

the light of day, or ample gaslight. Let us be 'children of the day.“53

Such negative

reactions had an intriguing effect on the way some mediums began to conduct

materialization performances in the two decades that followed the Civil War.

In a radical reversal

of previous seance stagecraft, a number of materialization mediums actually

began performing under full light. If critics were turned off by the heightened

potential for fraudulent behavior in the dark, these mediums reasoned, then they

would simply keep the lights on. Daniel Dunglas Home, a particularly popular

medium who traveled across the United States and performed before European

royalty, seized upon the public's growing dissatisfaction with the dark seance

and used it to his advaritage. Home was banking on

the fact that by welcoming light into the seance he would be able to better

emphasize, in the words of a British historian of spiritualism, "the

difference between himself and the majority of mediums who found virtually

complete darkness most conducive to spiritualist phenomena." As he had

expected, the move increased his popularity. Spectators, "after straining

their eyes to perceive the manifestations produced in the presence of other

mediums," found themselves "startled to observe phenomena occurring

in fair light.“54

Other mediums also

shifted gears when it came to performing under lights, and exploited their

willingness to banish darkness from their seances as a powerful marketing tool.

They deduced that if run-of-the-mill materialization mediums were still tied to

the "old" practices of the dark seance, then they were

revolutionaries truly worthy of the public's notice. Mary Huntoon, a sister to

Horatio and William Eddy, reportedly jumped at the chance to distinguish

herself by performing under lights. According to an article published in 1867

in the Banner of Light, Huntoon would sit in front of her "cabinet in

lighted halls and parlors, skeptics holding her hands," and yet

materializations supposedly continued "both within and outside the

cabinet." Another report in the Banner was even more pointed about the

alleged abilities of a medium only identified as "Mrs. Cushman,"declaring

that her seances would be especially interesting to skeptics because they were

done in the light. This factt stated the papert destroyed "the argument of the unbelievers'.'

that "darkness is always required to produce" spirit

materializations. 55

Historical sources

reveal a real physical intimacy between medium, audience, and

"spirit" in most materialization seances, a closeness that was not

present in the heavily oral/aural performance of trance speaking. Trance

lectures often were big eventst held before large

audiences in spaces that were primarily designed with acoustic considerations

in mindt such as auditoriums or lecture halls.

Materialization performances were different. The venues mediums chose for

materialization seances tended to be much smaller; sometimes they were simply

rented rooms above small storefronts where spectators were forced to jam

themselves together in a few rows of seats just feet from the spirit cabinet.

Through the careful selection and manipulation of these spacest

however, as well as through the exploitation of their own bodies, public

mediums perpetuated the illusion of spirit materialization and convinced at

least some spectators that they really could make spirits appear.

We can look to the

Eddys' seance room on their Vermont homestead as a useful example of what a

typical materialization seance venue looked like. The detailed description we

have of the Eddy seance room is an ironic product of the research Henry Steel

Olcott did as part of his campaign to rule out natural sources of séance

phenomena.

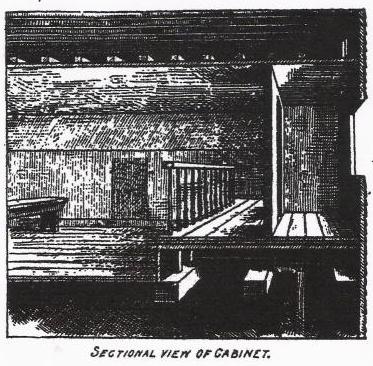

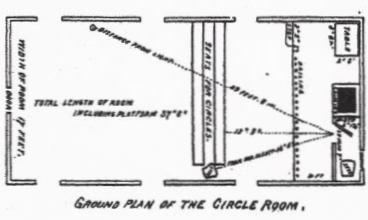

According to Olcott,

the room was part of an L-shaped vertical addition to .the Eddys' original

home. At one end of the room stood a platform; on it was a closet that served

as the mediums' spirit cabinet. The closet's dimensions-it was only a little

more than two feet wide by seven feet long-were likely advertised to observers

as only large enough to accommodate the medium, leaving no room for

confederates to hide.

Knowing that skeptics

would still wonder about the integrity of the closet, however,Olcott

stated that there were "no panels to slide" in the closet, and

"no loose panels on the floor to lift. Every inch is tight and

solid." The only way an accomplice could reach the closet, Olcott claimed,

was through an exterior window, but he had received permission to seal it up

with "fine mosquito netting." He also posted someone outside the

window to ensure that the medium was not receiving external aid, at least while

he observed the Eddys for his newspaper. 56

Beyond the closet,

the rest of the seance room was equally small, measuring only thirty-seven feet

by seventeen feet-a far cry from the auditoriums where trance speakers

performed.

Above the room,

Olcott observed, was an unfloored cock-loft, but "there is no sign of [a]

trap or opening" leading into it. The audience normally sat in two rows on

hard wooden benches; according to a diagram Olcott drew as part of his investigations,

they sat a mere thirteen feet away from the closet door, with the Eddy family

(minus the medium for the day--either William of Horatio ) generally sitting on

the front row. In Olcott's mind, the audience's relative proximity to the

closet door practically guaranteed that spectators would be able to identify

the supposed spirits of their dead loved ones with a great amount of certainty.

There was a balustrade that separated the stage from the rest of the room, but

Olcott's account seems to indicate that "spirits" regularly left the

platform to mix with the audience, giving spectators an even better look at

them. (With a single gaslight perched nearly thirty feet away, behind the

audience, however, a little more skepticism on the writer's part would have

been warranted.) Some spectators even touched the supposed spirit beings;

one-the "shade" of the Native American woman Honto-acquiesced

to let a woman seancegoer feel her heartbeat. In a

scene tinged with homoeroticism, Honto "opened

her dress" and the woman placed "her hand upon the bare flesh."

According to Olcott's retelling of the story, her skin "felt cold and

moist, not like that of a living person. The breast was a woman's, and the

heart beat feebly but rhythmically." Thus despite the apparent barrier of

the stage railing, "spirits" tended to interact directly with

spectators: the close proximity of the crowd to the stage actually seemed to

invite it. 57

1 Virginia Ingraham Burr,

The Secret Eye: The Journal of Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas (Chapel Hill:

University of North Carolina Press, 1990), 222-224. This passage is dated 15

April 1864. The manuscript version of the journal (in 13 volumes) is held by

Duke University Library.

2 Ibid., 29-30,163,

222, 231. The various passages referred to here are dated 12 February 1858, 15

Apri11864, and 27 August 1864.

3 Ibid., 231-232,

240-242. This passage is dated 27 August 1864. On American Calvinist notions.

of death, see David E. Stannard, The Puritan Way of Death: A Study in Religion,

Culture, and Social Change (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), esp. 89.

4 Ibid., 337. This

passage is dated 29 September 1870.Thanks for your explanation which coming

from an experienced MD as you obviously are, is of great interest.

5 George C. Bartlett,

The Salem Seer: Reminiscences of Charles H. Foster (New York: Lovell, Gestefeld, and Company, 1891),44-45

6 Ibid., 130.

7 Salt Lake Tribune,

18 November 1873; and Ronald W. Walker, Wayward Saints: The Godbeites

and Brigham Young (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 116.

8 Burr, Secret Eye,

28 and 231. The first page citation here refers to Nell Irvin Painter's

introduction to the journal in its published form. The second citation refers

to a passage dated 27 August 1864.

9 Ibid., 337-338, and

369. These passages are dated 29 September 1870 and 12 April 1871.

10 Banner of Light

(Boston), 12 June 1858. The Banner of Light will hereafter be referred to as

BL.

11 Karen Halttunen,

Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America.

1830-1870 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), 130; and Gary Laderman, The

Sacred Remains: American Attitudes Toward Death, 1799-1883 (New Haven: Yale University

Press, 1996),55. See also Mary Louise Kete, Sentimental Collaborations:

Mourning and Middle-Class Identity in Nineteenth-Century America (Durham, North

Carolina: Duke University Press, 2000).

12 Spiritual

Scientist (Boston), 20 May 1875; and BL, 2 September 1865. The Spiritual

Scientist will hereafter be referred to as SS.

13 Martin Jay,

Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth Century French Thought

(Berkeley: University ofCalifomia Press, 1993),45 and

65. Jonathan Crary's work on the nineteenth century is equally useful on this

point. See Crary, Techniques o/the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the

Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990).

14 Leigh Eric

Schmidt, Hearing Things: Religion, Illusion, and the American Enlightenment

(Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2000), 22 and 26. See also

Alain Corbin, Vii/age Bells: Sound and Meaning in the

Nineteenth-Century French Countryside (New York: Columbia University Press,

1998); and Mark M. Smith, Listening to Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill:

University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

15 Benjamin McArthur,

Actors and American Culture, 1880-1920 (Iowa City: University ofIowa Press, 2000), 3-4. On Gordon, see Henry C. Gordon

and Thomas R. Hazard, Autobiography of Henry C. Gordon: And Some of the

Wonderful Manifestations Through a Medium Persecuted From Childhood to

Old Age (Ottumwa, Iowa: Publishing House of the Spiritual Offering, 188-7)

16 SS, 21 August

1876.

17 Ibid., 25 January

1877.

18 Ibid.

19 [Joel Tiffany],

"The Day of Trial," Tiffany's. Monthly, February 1859,365-373.

20 Philadelphia

Press, 19 March 1884. The infonnation on actors'

salaries comes from McArthur, Actors,23. The Philadelphia Press will hereafter

be referred to as PP.

21 BL, 25 December

1870, May 21, 1864, and 5 March 1864.

22 Ibid., 18 June

1864.

23 Mary Dana

Shindler, A Southerner Among the Spirits: A Record of Investigations into the

Spiritual Phenomena (Memphis: Southern Baptist Publication Society, 1877), 27

and 40-43.

24 John W. Edmonds

and George T. Dexter, Spiritualism (New York: Partridge and Brittan, 1853), 2:

261-263, quoted in Robert S. Cox, Body and Soul: A Sympathetic History of

American Spiritualism (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003),

136.

25 Robert W.

Johannsen, To the Halls of the Montezumas: The

Mexican War in the American Imagination (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1985), 59; David Waldstreicher, In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of

American Nationalism, 1776-1820 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina

Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1997),

119-120; Alfred F. Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the

American Revolution (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999), 117; Brooks McNamara, Days of

Jubilee: The Great Age of Public Celebrations in New York, 1788-1909 (New

Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 148-149; and Karal Ann Marling,

George Washington Slept Here: Colonial Revivals and American Culture, 1876-1986

(Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1988), 1 and 115-150.

26 Henry S. Olcott,

People from the Other World (Rutland, Vermont: C. E. Tuttle, 1875), 141, 191.

27 Ibid., 135-136,

194.

28 Ibid., 135.

29 Shindler,

Southerner, 61-62; and Olcott, Other World, 225.

30 Olcott, Other

World, 62-65.

31 Ibid., 65.

32 BL, 22 September

1877; and Shindler, Southerner, 29-36.

33 Olcott, Other

World, 65.

34 We are not using

this term here to refer to the iconographic nationalism or imperialism of

nineteenth-century landscape painting as Angela Miller does in her book The

Empire of the Eye: Landscape Representation and American Cultural Politics.

1825-1875 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993). Rather, we am using this

term to refer to the powerful place a visual regime was able to stake out as

part of the nineteenth-century American sensorium.

35 William Leach,

Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture (New

York: Vintage Books, 1993). Even goods in rural stores were arranged so as to

attract the eyes of customers. See Thomas J. Schlereth, "Country Stores,

County Fairs, and Mail-Order Catalogues:Consumption

in Rural America" in Consuming Visions: Accumulation and Display of Goods

in America, ed. Simon J Bronner (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1989),

350-351.

36 David M. Henkin,

City Reading: Written Words and Public Spaces in Antebellum New York (New York:

Columbia University Press, 1998),64.

37 Wolfgang

Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night: The lndustrialization

of Light in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley: University of California,

1998),143-145.

38 GarffB. Wilson, Three Hundred Years of American Drama and

Theatre (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1982), 37; and.John L. Fell, "Dissolves by Gaslight: Antecedents

to the Motion Picture in Nineteenth-Century Melodrama," Film Quarterly 23

(Spring 1970): 30.

39 Tim Fort,

"Steele MacKaye's Lighting Visions for The World Finder," Nineteenth

Century Theatre 18 (Summer and Winter 1990): 35-36; Lise-Lone Marker, David

Belasco: Naturalism in the American Theater (Princeton: Princeton University

Press, 1975), 78.79, 82; quoted in David E. Nye, ElectrifYing