By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The U.S., U.K.,

Australia and India each fall under the umbrella of the common law family,

although the legal tradition of each maintains unique aspects. Each of these

four states has also been active in the past several decades in participating

in UN actions and sending its troops to various areas, whether as part of a

peace-keeping team or as another type of force.1 Moreover, each of these states

has been engaged in armed conflict with another state in the last half century.

This means that each of these four states has had to consider the issue of

whether their personnel could be accused of a crime and brought before the ICC.

These similarities provide for a common background from which to examine the

interpretations made by the four states, and given their similarities in

historical legal development and current contemporary actions, isolating the effect

of the various attributes of legal tradition should be possible.

The legal traditions

of both the United States and Australia have been discussed in part three and four,

respectively.

Universal Jurisdiction

Universal

jurisdiction provides entities (in this case the ICC) with the authority to try

persons for crimes, whether or not the person is a national of a particular

state or the crime was committed in or against a particular state or its

citizens. Universal jurisdiction is applicable to those crimes which are

considered an affront to the international community as a whole, such as

genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. While long recognized in

international law, particularly in relation to states’ right to combat piracy,

the current conception of universal jurisdiction has only been considered an

international legal principle since the Nuremburg trials at the end of WWII.2

It has been re-codified in each of the treaties establishing the international

criminal tribunals and special tribunals over the past several decades and is

the core component of the International Criminal Court.

Historically, the

idea of a universal principle of jurisdiction was limited to states’ ability to

prosecute pirates, whatever their nationality happened to be3. More modern

understandings of this legal principle attach primarily to human rights

violations4; those crimes that are so universally condemned that any nation in

the world has the authority to exercise jurisdiction over suspects and

perpetrators, without the consent of that individual’s state of nationality.5

As with the other legal principles examined in part 3 and 4 , the United States

played a key role in the development of universal jurisdiction, serving as a

leading proponent of the Nuremburg trials, as well as the Security Council

resolutions authorizing the international criminal tribunals for Rwanda and the

former Yugoslavia. The U.S. has even recognized the veracity of this principle

within its domestic law, with both the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and the

Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals identifying human rights violations as acceptable

bases for a state to maintain universal jurisdiction over an individual when

neither the persons involved, nor the crime itself, have any direct relation to

the state6. Rather the jurisdiction stems from the harm to all mankind, as well

as international peace and security.

Currently, the

concept of universal jurisdiction has been expanded somewhat, largely through

the efforts of individual states. The desire has been to allow for the

prosecution of any individual accused of committing any crime which offends the

sense of global humanity. Some of the best known recent examples of this

expansion include the British High Court’s decision to allow the extradition of

Augusto Pinochet to Spain to stand trial for actions committed while he was

head of Chile, and Belgium’s 1993 law which allows Belgium to prosecute persons

for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity on the basis of universal

jurisdiction in absentia.7

Specifically in the

context of the International Criminal Court, the concept of universal

jurisdiction provides for prosecution of individuals accused of crimes of

genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity committed after July 1, 2002,

the date the Rome Statute entered into effect.8 One caveat, however, is that

the crimes committed must of such a grave nature as to rise to the level of

crimes which are of concern to the international community as a whole.9 It is

this conception of universal jurisdiction which states evaluated when

determining their position on the ICC.

Traditional theories

of international relations focused on power and interests would hypothesize

that no state would accede to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal

Court unless it would improve its power position within the international

community by doing so, or in some other way improve or protect its interests.

Given the obligations undertaken by a state party to the ICC, and the

relinquishment of a certain sense of sovereignty to become a party, it is

likely these theories would posit no state would sign on to the ICC statute

unless the most powerful states also agreed to do so.

Upon closer

examination, however, these traditional theories fall short of being able to

explain state participation in the ICC.10 For example, for the realists, an

international legal institution such as the ICC is unlikely to be created in

the first place because it is

contrary to the fundamental notions of state sovereignty, and the freedom of

states to act as they see fit to protect their interests. Yet created it was;

and even though they all did not ultimately sign on, most members of the United

Nations participated in the sessions drafting the Rome Statute.

Moreover, realist

theory would contend that if an international criminal court was Created, it

would only be created by powerful states to further their own purposes. Yet, in

the case of the ICC, many of the most powerful states – the United States, China,

India, and Russia among them – are all opposed to the Rome State. Despite this

opposition by the powerful states, however, the Rome Statute entered into force

and presently has 139 parties, even though none of the four states listed above

has changed its mind. Neo-liberal institutionalist theory as well faces some

problems in adequately trying to explain state acceptance of the Rome Statute.

According to Wippman:

[A] neo-liberal

institutionalist analysis, which sees states as rational actors in pursuit of

efficient means to realize individual and collective interests, captures only

part of what transpired at Rome. To some extent, the Rome treaty was motivated

by a desire to solve collective action problems and to reduce the transaction

costs inherent in establishing ad hoc tribunals. But the Rome treaty was driven

even more fundamentally by a desire on the part of many participants in the

negotiations to develop and stabilize norms of legitimate behavior by states

and non-state actors. … [R]ationalist analysis works

best in areas where states can plausibly be seen to have clear, pre-existing

material interests; it does not work well in explaining the creation of

international organizations such as the ICC that are driven in significant part

by normative as well as material impulses.11

Because the primary

function of the ICC is normative in its foundations, the organization does not

function they way institutionalists might argue it should in order to garner

the support of states.

The incongruency of

the establishment and entry into force of the Rome Statue of the International

Criminal Court with traditional international relations theory calls therefore

for new explanations for state behavior. Given the normative component of the

ICC, and the fact that it does require relinquishment of sovereignty as well as

put normative constraints on state behavior in terms of what is the appropriate

course of action, an explanation devoted to understanding the cultural and

normative reasons behind state action – such as that concerning legal tradition

– is necessary. In particular such an explanation “requires consideration of

how actors’ interests and identities interacted to produce positions on

particular contested issues.”12

Two forthcoming works

which do consider legal tradition address some of these concerns. In her

forthcoming work on human, Beth Simmons examines the differences between common

law states and civil law states in their adherence to international human rights

treaties.13 She suggests that, due to variation between the common and civil

law, civil law countries are more likely than their common law counterparts to

commit to international human rights treaties. While Professor Simmons includes

components of legal tradition in her analysis, focusing in particular on the

fact that the use of precedent and the power of the judiciary present in the

common law systems is absent in the civil law system. However, in the her final

analysis she retains the common law/civil law division, grouping states

generally in one of two categories. While this may provide initial evidence as

to the differing behavior of the two types of legal traditions, I suggest that

this will not fully explain state behavior. Within the civil law tradition,

there are state from Europe, Africa, Asia, and South America, each of which

adhere to the general tenets of civil law outlined by Simmons – adherence to a

code-style of law and the integration of the judiciary within the government –

but which are significantly different in the overall attributes of their legal

traditions, and which behave very different in terms of international law. The

same, this chapter seeks to demonstrate is true for the common law nations,

even though there are many fewer of them.

A second piece by

Sara McLaughlin Mitchell and Emilia Powell, forthcoming in the Journal of

Politics, also makes an argument incorporating legal tradition. Mitchell and

Powell examine state acceptance of the jurisdiction of the International Court

of Justice and seek to understand the characteristics which make a state likely

to accept the absolute jurisdiction of the ICJ versus an acceptance of

jurisdiction with reservations.

Mitchell and Powell

look at three different legal traditions – the common law, the civil law, and

Islamic law – but like Simmons, lump state’s under these general headings

without delving into the differences among them. As stated in the previous

paragraph, we suggest that this general categorization does indeed improve on

earlier work which does not consider legal tradition at all, but it still

leaves much room for improvement because it fails to explain the frequent

differences which occur within the general legal families.

(A) United States

As discussed in

chapter four, the legal tradition of the United States is very closely tied to

the revolutionary ideals which prompted the creation of the United States

Constitution, and country’s subsequent political and legal structure. This

includes a foundational institutionalization of the separation of powers and a

significant role for the judiciary, as well as subsequent actions including the

creation of a Bill of Rights and the focus on an entrepreneurial spirit. These

influences have resulted in the U.S. legal tradition possessing the following

attributes: a purpose of law focused on the individual; the primary

responsibility for the creation and amendment of law found in the judicial

branch; a dualist approach to international law; and a hierarchy of sources of

law which places the U.S. Constitution as the apex, and the decisions of the

judiciary – as the final arbiters of the Constitution – second.

As described in P. 3

of this investigation, these attributes of the U.S. legal tradition hinder the

relationship between domestic law and international law within the U.S.

tradition. Given the focus on individual rights and freedoms and the underlying

belief that law should be used as a mechanism by which to punish actions which

have infringed on individual liberties, not to prevent individuals from acting

in the first place, the idea that international law could affect these

protections is one that is an anathema to the understanding of the role of law

in the United States. Again, this is not to say the United States does not

respect the rule of law, including the rule of international law, because

indeed it does. The United States, as demonstrated, is often a leader in terms

of pushing for new concepts of international law, offering expanded

protections. Moreover, the U.S. couches much of its diplomacy in the language

of international law, and always has. The issue is not with the U.S. belief in

the value of international law over the broad course of the country’s history.

The issue is that due to the way the U.S. legal tradition has developed over

the past 250 years, there is an extreme reluctance to accept any outside

interference with the foundational legal principles of the state, as well as a

penchant to view international law as being as changeable and immutable as the

law of the United States.

(B) Australia

Australia, like the

United States, has the historical origins of its legal tradition in the common

law of England. As described in chapter five, however, the development of the

legal tradition from these origins has been influenced by different factors and

taken a slightly different track in Australia than in the United States. With a

much longer period as a British colony, with its history as a penal colony run

by an authoritarian governor, and with independence not grounded in a

revolutionary movement, but rather stemming from an Act of the British

Parliament, the foundations of Australia’s tradition do not maintain the same

sacred aura as that of the United States. Moreover, whereas the Australian

tradition does share similarities to that of the U.S. in terms of the respect

for individual freedoms and entrepreneurship, the translation of these freedoms

into a sacred respect for individual rights enshrined in a constitution, does

not exist in Australia.

This history has led

to the development of the following attributes in the Australian legal tradition:

a focus on the individual in terms of the purpose of the law, but a focus

centered on individual freedoms along, rather than individual rights and

freedoms as in the U.S.; a system of judge-made law, but also a system in which

more power is left to the states vis-a-vis the federal government; a dualist

approach to international law; and, a hierarchy of sources centered on judicial

decision and parliamentary statute. The Australian Constitution plays a much

less significant role in the Australian legal system than does the U.S.,

largely due to the absence of a Bill of Rights. As with the U.S., these

attributes can hinder the relationship between international law and domestic

law within the Australian legal system. This, in turn, can influence the method

of interpretation a state adopts towards a principle of international law. In

the Australian case, there also appears to be a general reluctance to too

completely accept the binding effect of international law, largely due to the

country’s colonial history and its independent nature.

(C) United Kingdom

As discussed before

in this investigation, the origins of the common law tradition come from

England. It was in England in 1066, that William the Conqueror planted the

seeds for the common law system by centralizing judicial authority at

Westminster14. In order to reign in the chaos that numerous local systems of

law can have on a unified legal system, the first judges began collecting the

laws common to the majority of the people and applying those uniformly to all

court cases15. It is from this – the identification and application of the law

common to all – that we get the name for the common law tradition. From this

starting point, many of the attributes most closely associated with the common

law tradition developed, including: the supremacy of judicial decision as the

primary source of law and as the source of the creation and amendment of law

beyond the sovereign16, the focus on the individual case, as opposed to the

communal well-being, through the disposition of judicial proceedings; and the

separation between domestic law and foreign affairs17.

Despite these common

origins, however, as is evident from the cases of the United States and

Australia described above, subsequent developments in each state’s legal

tradition have resulted in slightly different attributed among the four states

– even though they all have the same foundations. In England this legal

development included three primary factors which have had a subsequent

influence on what today is the legal tradition of the United Kingdom. The first

of these is the emergence of Parliament as the primary force for creating and

amending law in the U.K. No longer are the courts responsible for this task. In

fact, in a complete opposite trajectory of development from that of the United

States (where courts have steadily gained power over the years), the courts in

the U.K. have steadily lost power. This is due to a number of factors,

including reactions to the authoritarianism of the monarchy and the desire to

have the government better represent the people18; the creation of the United

Kingdom, which joined together the common law system of England, with the Roman

law system of Scotland, and the customary legal system of Wales; and, the lack

of a written constitution in England to dictate the separation of powers and

the authority of the Court. Not only does this latter omission mean that no

constitutional power is specifically dictated to the judicial branch, but it

also means there is no document upon which the justices can base an attempt to

gain more power (as the Marshall Court did in Marbury v. Madison)19.

The second factor

which has pushed England in a different direction than its common law heirs,

is, as mentioned in the previous paragraph, the lack of a written constitution

and the impact that has on all manner of political and legal structures. Much

of what gives the United States its unique legal tradition is the foundational

nature of the U.S. Constitution, and the close relationship between the fight

for independence in the U.S. and how people understand the Constitution as a

continuation of those ideals20. The United Kingdom, on the contrary, lacks both

a similarly significant foundational moment in terms of its own perceptions of

itself, as well as any core written text outlining the institutions of the

country. The “constitution” of the United Kingdom is rather composed of a

series of documents that span both time and type of law21, and includes the

Magna Carta (1215)22, the Petition of Right (1628), the Bill of Rights Act

(1689) 23, the Act of Union with Scotland (1707), the European Communities Act (1972)24,

and the Human Rights Act (1998). Coupled with this, the institutions of the

U.K. have developed over time, and in a relatively non-confrontational manner.

Much of this, we suggest, is due to the continuous overarching presence of the

monarchy which, even when it itself was the object of complaint, maintained a

certain institutional structure within the state. This has resulted in an

interrelated set of institutions that have developed over time, not by the

dictates of a foundational legal document such as a constitution, but rather by

the practicalities of the changing nature of society as a whole. This creates

very different perceptions of law in the U.K. than in the U.S. or Australia25.

The third influence

that has shaped the legal tradition of the U.K. over the past 50 years, and is

the dominant force responsible for the shift in the U.K.’s interpretation of

international law, is the U.K.’s membership in the European Union. Up to the point

of World War II, the attributes of the British legal tradition fairly closely

mirrored those of the United States, save for the decreased power of the U.K.

courts compared to their American brethren. Both states largely focused on the

individual in terms of the purpose of their laws, and the judiciary played a

significant role in each states legal system.

Moreover, both the

U.K. and U.S. were largely dualist in their approach to international law,

preferring to ‘go it alone’ or work in a specific, negotiated international

framework rather than under the rubric of binding international law. With the

end of the war, however, and the realization by the European states that

preventing another war on the continent had to be a top priority resulted

ultimately in the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community, which

ultimately morphed into the European Union, a regional organization with its

own legal personality, to which member states surrender of good deal of

sovereignty. Upon becoming a member of the EU in 1973, the United Kingdom

became subject to the same limits on its sovereignty. Moreover, as the EU

continued to grow, expanding its authority over areas such as human rights and

social issues, the attributes of the British legal system began to change to

fulfil its obligations as a member of the EU. These changes resulted in

somewhat different attributes of the British legal tradition today than were

seen prior to the 20th century.

(1) Purpose of Law

Due to the historical

importance of conflict being solved through the court system, the purpose of

law in the United Kingdom is largely still viewed as one which provides

protections for individuals in making their claims26. However, this focus on

the individual, rather than creating a strong sense of law promoting what is

best for the community, has been eroded somewhat over the past century, both by

an emerging socialist trend “attempting to create a new social order”27, and by

the U.K.’s membership in the European Union. The EU, given its focus as a

regional organization, is communal in nature. The entire idea behind the

European Union was that the creation of closer cooperation between European

states would lessen the likelihood of states engaging in conflict with each

other over their individual interests. Rather, closer cooperation would cause

states to think of what is best for the community. This has become reflected to

some extent in the British legal tradition. For example, the U.K. has signed on

to the European Convention on Human Rights and has accepted both European Court

of Human Rights and European Court of Justice jurisdiction over the disposition

of cases. This treaty, as well as the workings of these courts, focus on the

communal purpose of law rather than the individual.

There has not been a

complete shift in the view by the British of the purpose of law. The U.K. still

retains sovereignty over certain areas, such as a number of social issues,

rather than relinquish sovereignty to the EU. The U.K. also maintains its independence

in terms of monetary policy, immigration policy, and national security and

defense. In these areas, the U.K. is still reluctant to accept outside

interference with its sovereignty as an individual state. In the same way, the

purpose of law in the United Kingdom is still viewed in many areas as

protecting the rights of the individual, rather than fostering the good of

community28. Outside interference with individual freedom of action is still

often frowned upon, but is viewed with less suspicion that, for example, in the

United States.

(2) Legal Institutions

The British

institutional structure is much more similar to that of Australia than it is to

the United States. Britain maintains a parliamentary system with a monarch as

the head of state and a prime minister as the head of government. Without a

written constitution, the relationships between the branches of government have

developed by custom over time. While a democracy with a modern government, the

concepts of separation of powers and checks and balances that dominate the

perception of institutional structure in the United States do not exist29. This

is most evident in the interrelationship between the executive and legislative

branches in which the Prime Minister, the principle member of the executive

branch, survives only at the favor of Parliament30. The interrelationship does

not end there, however, for the House of Lords, the highest judicial body in

the United Kingdom, is also composed of members of the upper house of

Parliament. Despite this, however, the judiciary in the United Kingdom does retain

its independence from the other branches of government, although it does not

hold the power of checks and balances the U.S. Supreme Court does.

Moreover, within the

English tradition it has become the purview of parliament to create and amend

the laws, not the judiciary. While historically it was the judiciary which was

responsible for such actions, this changed in the 18th and early 19th centuries

when the people revolted over the dominance held by the monarchy and upper

classes over all branches of government31. As in France, the judiciary were

seen as being a part of the upper class and under the influence of the

monarch.32 In the latter half of the 19th century these beliefs came to be

codified in the perceptions of “almost all politicians, lawyers, and political

theorists … that Parliament possessed a legally unlimited legislative authority

within Britain” and by 1871 it was held that the courts had no authority “to

act as regents over what is done by parliament.”33 These laws gave the

preponderance of power to the parliament, as representatives of the people, as

opposed to the courts overseen by the aristocracy. This set-up remains to this day.

Today, the legal system in the U.K. is such that parliament is the only

institution which can make and amend laws. This notion of parliamentary

sovereignty is “central to English constitutionalism”.34 The courts are

responsible for interpreting the law, but may not judge an act of parliament

invalid35. This gives a preponderance of the power over legal enactment and

amendment to the parliament, which is an attribute more closely aligned with

civil law traditions like that of France, than common law traditions like that

of the United States.

While the creation

and amendment of law may differ in the United Kingdom, however, the U.K.’s

approach to international law remains largely similar to that of both the U.S.

and Australia in that it is generally dualist in nature.36 As stated by Rosalyn

Higgins and quoted in chapter five, the common law countries adhere “resolutely

to the dualist approach.”37. However, as mentioned above, the absolute nature

of this approach has shifted slightly in the United Kingdom as a result of the

country’s membership in the European Union. EU membership automatically

requires states to relinquish a modicum amount of sovereignty to an

international organization. Moreover, EU membership dictates that member states

are responsible for implementing EU regulations into their domestic legal

systems. For all EU members, therefore, this has required domestic legal

changes authorizing a monist approach to EU legislation. Therefore, the U.K.

has become essentially monist in their approach in any areas over which the EU

has primary control. However, in those areas in which the U.K. retains national

sovereign control, the state remains true to its dualist origins.

(2) Sources of Law

The U.K. differs from

the United States in that it has neither a written constitution to serve as the

foundational source of law38, nor do judges have the power of judicial

review39. As explained in the case of the U.S. in part four, the principle

reason the judiciary remain the primary source of law in the United States –

even though the amount of statutory law has increased dramatically – is that it

is the judiciary which is responsible for the ultimate determination of the

meaning of both the U.S. Constitution and any federal law passed by Congress.

Because the U.S. retains the power of judicial review, this gives the U.S.

judicial branch enormous power and authority. This is not the case in the

United Kingdom. While the British judicial branch retains the power of

precedent, it does not maintain ultimate authority over the interpretation of

law; that right belongs to parliament40. While legislation has traditionally

“occupied only a secondary position in English law and was limited to

correcting or complementing the work accomplished by judicial decision”, today

the relative position of the two sources of law is largely reversed41.

Therefore, parliamentary enactments are the primary source of law in the U.K.,

rather than judicial decisions.42

Given the historical

importance of judicial decisions for the development of the British legal

tradition, however, judicial decision and case law still holds a pride of place

in the conceptions of many British citizens when it comes to sources of law43.

Therefore, even

though the power of the judiciary in England may not be what it once was, case

law is still seen as the primary foundation of the U.K.’s legal tradition44.

This has an important implication for the influence that legal tradition may

have on a state’s interpretation of international law. As discussed in chapter

four in relation to the United States, a belief in law as primarily a

judge-made entity creates a different perspective about the changing nature of

law. By its very nature, a legal system based on judicial decision is a

bottom-up system, where individual cases come before the court and changes in

the law come with new facts in the case. It is a system in which actions happen

first and judicial approval or disavowal of those acts happen second. Moreover,

while judges may not have the ability in the U.K. to review the

constitutionality of parliamentary action, they do maintain authority over

interpretation of the law, which can give them considerable power in

determining how law actually applies to the community.45 This creates a much

more flexible legal system, one which accepts a more malleable nature to the

law. This can then translate to international law as well.

The U.K. does retain,

however, the historical common law aversion to doctrinal writings being

considered as sources of law46. The laws of the U.K. are not laws of the

universities47. Given the historical important of the judiciary in the

development of the British legal tradition, it was the judges who were

considered the legal experts, not scholars48. Therefore, as in the U.S. and

Australia, scholarly writings have never taken on the importance they have in

other countries such as France and Germany where judges were not long-schooled

legal specialists and doctrinal writings provided valuable guidance on the law.

(D) India

India, today, is

considered part of the common law family. The history of India’s legal

tradition, however, is significantly different from that of either the United

States or Australia. For one thing, with over one billion people, India has a

larger population to govern than any country in the world except China.

Moreover, among these one billion are at least seven different major religious

groups, eighteen different official languages, and at least three major ethnic

groups49, not to mention residual beliefs in the caste system by elements of

the population.50 The influences which have shaped the development of the

Indian legal tradition are more varied than in the Anglo-Saxon states.

These include the Hindu

legal tradition, Islamic law tradition, and tribal or customary law. Moreover,

despite the modernity of India’s existing legal system, these ancient,

religious and tribal influences remain to some extent within the rule of law.

These differences notwithstanding, however, since Indian independence in 1950

India has been considered part of the common law family of states51. The

underlying structure of India’s legal system, as well as the general operation

of the rule of law in contemporary times, does place India in the company of

the other states discussed in this chapter52. India, therefore, provides an

interesting comparison to the U.K., U.S., and Australia as a modern common law

country, with ancient roots.

The three major

influences on the development of the Indian legal tradition are Hinduism,

Islam, and the British colonial presence. Each of these has its own individual

legal tradition, and the mixing of the three has shaped the nature of the India

tradition. Hinduism is the oldest influence on the Indian legal tradition, and

indeed, even today forms part of the core of the Indian legal system. The laws

of Hindu India can be traced as far back as 2500 BC. The Hindu tradition is

based on Dharma, which is the belief “that there exists a universal order

inherent in the nature of things, necessary for the preservation of the world,

and of which the gods themselves are merely the custodians.”53

Like the Shari’a in the Islamic legal tradition, Dharma in the Hindu

tradition encompasses the “whole of man’s behavior” and does not distinguish

between religious duties and legal obligations.54 Any concept of individual

rights is foreign to the Hindu tradition which, like the Islamic religious

tradition, focuses on maintaining balance and harmony within the community, and

the principles that each person must follow if they wish to be a good person

and reach the desired place in the afterworld55.

One belief that

distinguishes the Hindu tradition from that of the other religious legal

traditions, however, is that within the tradition the duties and obligations

each individual must carry out to be a good person and achieve their desired

place in the afterworld, varies according to each person’s status.56 The Hindu

tradition divides people into four primary social groups, each with its own

rules and obligations57. This division is necessary in the Hindu tradition to

ensure the proper balance within nature. This division is also the origin of

the Indian caste system, which has had a significant influence on the

development of the legal tradition of India, and continues to play a role in

the legal system of modern India, despite the abolishment of the caste system

in the Indian Constitution.

In the historical

Hindu legal system, rules were primarily enacted, implemented, and enforced at

the local community level58. The village panchayat was largely responsible for

hearing and deciding legal disputes on the basis of religious laws and existing

local custom59. Given the diversity which existed throughout the Indian

subcontinent60, there could be a significant difference between the laws as

applied in the local communities.

In the 16th century,

the Mongols invaded India and brought with them elements of the Islamic law

tradition61. While similar to the Hindu tradition in terms of general structure

– for example, in that laws could only be created by the gods and law covered

both religious and secular behavior – Islamic law is much more rigid in its

tenets than the Hindu tradition. Perhaps recognizing these differences, the

Islamic rulers did not impose Shari’a on the Hindu

population in the territories of India they commanded, but rather allowed

Hindus and Muslims to retain their separate traditions and rules of law62. Thus

a dual legal system sprang up in which Islamic law and courts applied for

Muslims and Hindu law and courts applied to Hindus. Into this situation of dual

legal traditions arrived the British. Britain first gained a toehold in the

India sub-continent through the East India trading company in the 17th

century63. After the decline of Dutch and Spanish naval power, however, India

came fully under the authority of the United Kingdom. As was often the case

with their colonies, the U.K. did not impose British law on the Indian

population at the expense of their traditional legal system64. Rather, both the

Hindu and Muslim populations were able to continue to apply their own laws at

the local level. British law applied, in theory, only to British citizens and

in those circumstances where there was no local law or in which local law

offended the British sense of justice65.

Practically, however,

the British presence in India had a profound influence on the development of

the India legal tradition, both in terms of the recognition of Hindu law and in

terms of the growth and development of that law. As to the former, the recognition

by the British of both Hindu and Islamic law as equally valid legal systems,

moved Hindu law out of the shadows from which it operated while India was under

Mongol control.66 At the same time, however, despite the best efforts of

British judges to apply traditional law to cases between Hindus, the absence of

authoritative English translations of Hindu laws coupled with over-reliance on

Hindu “legal specialists” led to a distortion of the traditional Hindu law67.

The results of this, as well, were both positive and negative. Positive in that

the centralized nature of the British system allowed for the unification and

clarification of the extremely diverse legal rules which were found throughout

India68. This ultimately led to the creation of a national legal system69.

Negative in that the

historical extent to which Hindu law applied to govern all situations in the

lives of Hindus was dramatically reduced. Under the British rule, Hindu law

(and Muslim law as well) came to apply solely to those cases involving personal

status, such as marriage, birth, and death70.

The legal tradition

of India today has retained elements of each of these three primary influences.

While the majority of legal institutions are based on the British (or other

common law) system(s), at the local level, the use of religious laws still exists,

and is in fact recognized as valid by the federal law.

(1) Purpose of Law

The purpose of law in

India is centered on the community, rather than the individual. This draws both

on the historical religious influences on the legal tradition, as well as the

modern goals of the state’s post-independence legal system. As described in

part four in relation to Islamic law, religious legal traditions, by their very

nature, focus on a communal purpose of law. The goals of such legal traditions

are to ensure the well-being of the community as a whole, and that everyone is

able to achieve the best life possible in this world to attain the rewards of

the next. The Hindu tradition reflects that notion as well, focusing on the

harmony of the community and the balance of man and nature.

Modern developments

of the Indian tradition have furthered this focus of law on the community, as

opposed to the individual. First, resulting from the nationalist pride that

developed during the movement to gain independence from Britain, and later

stemming from the Indian government’s desire to protect the good of all members

of Indian society71. First, the development of Indian nationalism, as was the

case in Turkey and Egypt described in chapter four, created a greater awareness

of the need for a unified, continually-developed Indian community72. Given the

widespread divergence in economic and social status within the country, only

through a concentrated effort of protecting all members of Indian society was

it perceived possible for India to develop.

Second, despite the

abolition of the caste system in the Indian Constitution, there was still a

great deal of discrimination against those perceived to be of the lower

classes. One of the early goals of the post-independence Indian legal system

was to ensure the equality of everyone, even if that meant favoring the lower

classes at the expense of the privileged73.

This is reflected in

constitutional rules, not only abolishing untouchability, but allowing the

reservation of a certain number of seats for former untouchables in educational

institutions and places of public employment.74

This concept of a

communal purpose of law is further reflected in the Indian Constitution, which

defines the nation in the Preamble as a “sovereign socialist democratic

republic”.75 The Constitution also focuses on creating a unified society by

prohibiting discrimination based on social class. This is an effort to undo

thousands of years of history in which, as described above, Indian society was

divided by religious belief, into social classes, each of which was believed to

have its own place in Hindu society. Article 15 of the Indian Constitution

prohibits any form of discrimination based on caste.76 Moreover, the Indian

Constitution does not uphold ideas of equal protection in the same manner as

the United States, recognizing instead that “certain castes, tribes or

economically weak social groups should possess a special status.”77

Furthermore, the

governmental institutions of India are all guided by a separate series of

fundamental principles outlined in Part 4 of the Constitution, which call upon

them to frame every policy, piece of legislation, and judicial decision in such

a way as to establish and maintain a new social order in which justice –

whether social, economic, and political – shall inform all the institutions of

national life.78 These principles include such community-oriented tenets as

ensuring that ownership and control of the material resources of the community

are distributed to best achieve the common good, and the assurance that the

operation of the economic system does not lead to the concentration of wealth

and the means of production in the hands of the few to the detriment of the

common good.79

(2) Legal Institutions

The legal

institutional structure of India is a cross between that of the U.K., the US,

Ireland, and Australia. The drafters of the Indian Constitution drew from the

legal and political structures of all four of these common law countries when

they were setting up their postindependence system. Today, Indian maintains a

mixed presidential parliamentary system with the addition of a relatively

powerful President as well as a Prime Minister appointed by the President from

the legislative body.80 The preponderance of the authority lies with the lower

house of parliament, the 552-member Lok Sabha, which has the authority to enact

legislation, as well as dismantle the government through a vote of no

confidence.81 India does maintain an independent judiciary, and the judicial

branch possesses a level of power that is a cross between that of the U.K. and

that of the U.S. For example, while the Supreme Court of India does possess the

power of judicial review of legislation for conformance with the principles of

the Constitution, the ease with which Parliament can amend the Constitution

makes this a much less powerful tool in India than in the United States82.

However, given the view of the Indian population that the Supreme Court is the

most uncorrupt branch of the government and one of the most respected83,

politically it can be damaging for Parliament to amend the Constitution to

thwart a Supreme Court ruling.

The institution

primarily responsible for creating and amending law in India is the parliament.

As in England, the judicial branch is very active in creating a system of case

law based on the concepts of precedent and stare decisis84, but because there is

limited judicial review of the constitutionality of acts of the other branches

of government, the courts are without the primary power they possess in the

United States. The judiciary in India is consistently viewed by the Indian

public, however, as the most trustworthy of all of the government bodies, which

does give added weight to the authority of Indian judicial decisions as a

source of law (see below), but the judiciary is not primarily responsible for

making or amending law.

Following more

closely in the common law tradition, however, India maintains a clear dualist

position towards international law. With respect to international treaties to

which India becomes a party, separate action is required by parliament in order

for the treaty provisions to become binding law.

(2) Sources of Law

Historically, the

primary sources of law in India were the religious sastras and sustras, and the accepted interpretations of these works

(Vedas) by religious scholars. Legislation and judicial decisions were not held

to be sources of law under the Hindu tradition85. The prince was able to

legislate as necessary in order to order the community, but this legislation

was recognized only as a temporary need and was not able to conflict with or

supersede the tenets of Dharma86.

One important

criteria of the Hindu tradition, however, has always been its flexibility in

terms of the recognition of new laws. Unlike some other religious traditions,

in which change to the laws is very difficult to achieve, the Hindu tradition

accepts change as a natural part of life. The Dharma has “never purported to be

more than a body of ideal rules intended to guide men in their dealings.”87 Due

to its very nature, therefore, Dharma has always accepted that new laws will

have to be made by men to govern their current situations. Whether the laws are

created by custom, legislation, or judicial decision, the Hindu tradition has

always accepted manmade law as an essentially component of a functioning social

order, while at the same time recognizing the transient nature of this law and

the fact that it will continue to change and circumstances and societal needs

change88. This underlying attributed of the religious legal foundations of

Indian society has a profound influence on the perceptions of law held within

the country (and is indeed reflected in the malleable nature of the state’s own

constitution)89.

Today, the primary source

of law in India is the Constitution, followed by legislation90. India’s

Constitution entered into effect on January 26, 1950.91 While drawing on the

constitutional experiences of other common law countries, the Indian

Constitution is, however, very much unlike those of the other common law

countries in that, rather than serving as a relatively brief guide to

government structure and constitutionally-protected rights, it serves as a more

all-encompassing guide to government practice and individual behavior within

the state92. In fact, with its articles, is more akin to the Constitutions of

countries like Germany and Egypt, where the founding documents read more like

comprehensive codes than, for example, the U.S. Constitution93. The primary

objective of the Constitution is to ensure “social, economic, and political

justice to all citizens”.94

Because the Indian

Constitution is fairly easy to amend by parliament, and because the power of

judicial review of the Indian courts is minimal, judicial decisions do not

maintain the importance of place they possess in other common law countries.

The judiciary in modern India has, however, developed some authority on its own

as the most trusted branch of the Indian government.

Scholarly doctrine

may be considered a source of law in India, but largely within the realm of the

personal cases which may still be heard before religious-based tribunals. In

the same way, customary law still maintains a place in the Indian legal tradition,

but only through the local panchayat (meeting of the elders), which is able to

hear community and personal issues95.

One of the

overarching features of the modern Indian legal tradition, is the retention of

the influence of the ancient religious laws96. While practically speaking Hindu

or Islamic law is only applied by a few specific courts, in relatively few

cases, the influence of the religious traditions does continue to play a part

in the understanding of law within India. You see this reflected in the

continued understanding of the purpose of law as a communal endeavor. This

influence notwithstanding, however, the modern Indian legal tradition is one

closely related to its common law brethren, particularly in terms of

institutional structures such as the creation of law and approach to

international law. The latter attributes are sufficient for India to be

generally classified today as a member of the common law family. However, the

historical, religious attributes are enough to raise suspicions that India

might not approach international law in the same way as other common law

countries.

(E) Expectations

Given the fact that

each of the four countries examined has the origins of its modern tradition in

the English common law, many of the attributes of these countries are the

similar. In each of the four states the judiciary plays a greater role in the

creation and amendment of law than is seen in countries with foundations in the

civil law tradition. While none of the countries examined has a judiciary with

as extensive a power as that of the U.S. Supreme Court, judges do maintain a

special pride of place in the United Kingdom, Australia, and India. Moreover,

in each of the four states the use of the doctrinal writings of scholars as

authoritative sources of law is minimal in the creation, amendment, and

interpretation of law. Each of the four states, as well, generally adopts a

dualist position towards international law. Each of these attributes, as

described throughout the project, impedes the relationship between domestic and

international law.

This creates a sense

among policy-makers that international legal principles are not absolutely

binding in their existing form. This allows for the interpretation of

international law in new and different ways (although, again, as each of these

countries does generally adhere to the rule of law, including international

law, even new interpretations are firmly grounded in international legal

discourse).

Based on the general

categorization of these four states as members of the common law family, it

therefore could be expected that each of them would adopt a liberal

interpretation of international law: an interpretation grounded in the law, but

one which also allows for the consideration of state interests, changed

circumstances, and modern context. Indeed, this is the approach that is taken

by the existing work in the field which has dealt specifically with the

influence of legal tradition on state treatment of international law. These

studies have come to the conclusion that all common law countries, such as the

four examined here, would come to the same interpretation of international law.

To do so, however, would miss some of the very nuances that make the study of

legal tradition as an influential component of state policy-making a valuable

addition to the study of international law and international relations. The

very reason that such general classifications as common law and civil law do

not provide adequate explanations of state behavior is that each state

maintains slight differences in the underlying attributes which make up their

legal traditions and depending on the combination of these attributes the state

may or may not approach international law in the same way as other common law

states.

Based on more

traditional international relations theories focused on power and interests, it

would also likely be expected that each of these states would adopt a liberal

interpretation of international law, as it is the liberal interpretation which

gives a state the most freedom to consider its interests in formulation its

policies (again, none of these states will adopt an unrestricted interpretation

as they all adhere to the rule of law).

Given that each of

the four states has been active over the past decade in contributing troops to

United Nations missions, as well as regional missions, such as NATO in Bosnia;

and, given the fact the U.S., U.K., and Australia have been involved in conflicts

in Afghanistan and Iraq97, and India has been involved in continual skirmishes

with Pakistan98, there is a logical reason to expect each of the four to

approach the ICC in the same way. All four face also the potential that members

of their military or leadership will be indicted by the ICC. All four also face

the possibility of malicious or political cases being brought against their

citizens due to the unpopular nature of some of their actions. Based on these

similarities as well, under theories of power and interest it would also be

expected each of the states would interpret the international legal principle

of universal jurisdiction in the same way.

We believe however,

that these expectations are incorrect, and that, in fact, all four common law

states would not be expected to interpret the international law of universal

jurisdiction outlined in the Rome Statute of the ICC in the same way. The slight

variation among the states in terms of certain of their attributes, coupled

with the historical influences on the development of each countries legal

tradition, produces expectations that each of these four states might interpret

the international law of universal jurisdiction in a different way.

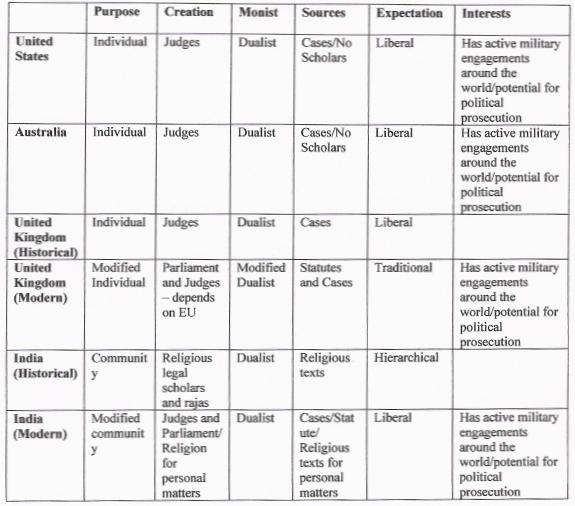

Table 1 summarizes

the attributes of the legal traditions of each of the four states examined

above. Both the United Kingdom and India have two columns. In the case of the

U.K., one identifies what the state’s attributes were before membership in the

European Union, and the corresponding expectation. The second identifies the

attributes and expectations since the U.K. became a member of the EU. For

purposes of India, the historical classification identifies attributes and

expectations prior to the imprint of the British tradition. The modern

classification highlights the attributes of the Indian legal tradition

post-independence.

The attributes of

both the United States and Australia, would lead to the expectation of a

liberal interpretation of international law. As discussed in the earlier parts

of his investigation, the attributes of the legal traditions of these states –

identical in all respects – lead to a disconnect between the recognition of the

binding authority of existing international law and the interpretation that

state decision-makers adopt.

An examination of the

pre-EU legal tradition of the United Kingdom would lead to the same

expectation. Prior to joining the European Union, the attributed of the U.K.’s

legal tradition were the same as those found in the U.S. and Australia. Again,

obviously, the historical development which led to these attributes differed

from that of the two other states, but the resulting attributes were similar

enough to produce an expectation of a liberal interpretation of international

law. However, the United Kingdom’s membership in the European Union has a

caused a shift in some of the attributes of the legal tradition. This is

particularly noticeable in the slight shift from an individual purpose of law

to a communal purpose of law, a movement from a strict dualist stance to a

mixed monist/dualist stance, and the increased recognition of statutory law as

the primary source of law. These shifts would be expected to create a closer

relationship between British domestic law and international law. This is

because, as discussed in chapters two and three, certain attributes facilitate

the internalization of international law, which creates a more binding sense of

obligation among decision-makers. Given this, expectations on Britain’s

interpretation would shift as well, and I would suggest the state could be

expected to adopt a traditional, rather than liberal, approach to the

international law of universal jurisdiction.

Finally, in the case

of India, what we might expect in terms of the pre-independence Indian legal

tradition differs from what would be expected from the post-independence

tradition. Prior to the arrival of the British, when India was still a country

dominated by religious legal traditions, it would be expected the state would

adopt a hierarchical interpretation of international law, just as Egypt does

due to the influence of the Islamic tradition. Post-independence, however,

after the common law influence of the British legal tradition has been

super-imposed over the historical religious origins, expectations change. The

shift from a religious tradition to a secular tradition has shifted some of the

attributes of the Indian tradition. While still largely focused on a communal

purpose of law, the secularization of the Indian tradition has shifted the

communal recognition from one based on religion to one based on nationalism. It

is possible this has a less profound effect on the societal understanding of law.

Moreover, with the

creation of British style legal institutions, there has been a shift in the

creation and amendment of law as well, from the religious based legal system,

to one in which a representative parliament is responsible for creating and

amending law.

There is also a much

greater role for the judiciary. In fact, the only attribute of the Indian legal

tradition which has not significantly changed over the course of the country’s

history is its strongly dualist approach to international law. There has never

existed an extremely close relationship between international law and Indian

domestic law. Again, this does not mean that India does not abide by or accept

international law, on the contrary, India like the U.S., the U.K., and

Australia is a country founded on the rule of law. What it does mean, however,

is that the relationship between domestic law and international law is less

likely to be absolute, and therefore, Indian decision-makers are less likely to

feel bound by existing international law, and more likely to therefore make

liberal interpretations of such law.

To summarize,

therefore, general expectations based on simple categorization of common law

countries would indicate all four states – the U.S., U.K., Australia, and India

– would adopt liberal interpretations of international law. Moreover,

traditional IR explanations focused on power and interests would hypothesize

that these states would similarly adopt an interpretation not requiring

adherence to the Rome Statute due to perceived dangers to state troops serving

abroad, and the relinquishment of state sovereign required to be a part of the

treaty. Our expectations, founded on the various attributes of legal tradition

rather than general categorizations, would be that the U.S., Australia, and

India would indeed adopt liberal interpretations of the international law of

universal jurisdiction – although for slightly different reasons – and the

U.K., largely due to its membership in the European Union, would adopt a

traditional interpretation. After examining the statements made by the four

states, it is clear that my expectations were met in three of the four cases.

The U.S., U.K., and India each adopted the method of interpretation expected.

Australia, on the other hand, rather than adopting a liberal interpretation as

they did in the case of the international norms of sic utere

adopted a traditional interpretation and signed on to the Rome Statute. While

Australia therefore did not meet expectations based on its attributes, an

explanation of Australia’s position in this instance can be found in a closer

examination of the historical development of its legal tradition. The position

adopted and justifications provided for each state in turn now.

First, the United

States was expected to adopt a liberal interpretation, and did in fact adopt

such as interpretation. As discussed in earlier chapters, the United States

recognized the legal principle at issue – indeed as in earlier cases was

instrumental in creating the legal principle at issue – but disagreed with the

existing interpretation of this principle as outlined in the Rome Statute of

the ICC. The United States provided a number of justifications for its position

on the Rome Statute. First, there is concern that adherence to the Statute of

the ICC would infringe upon the sovereignty of the United States in that it

would violate of the protections of due process provided by the United States

Constitution99. This would be contrary to the very foundation upon which the

U.S. legal tradition is built: the United States Constitution.100 The U.S. has

long been a supporter of the concept of universal jurisdiction. However, the

protections provided in the Statute of the ICC are not as stringent as those provided

in the U.S. Constitution. The U.S. cannot accept an international legal

principle which would be contrary to the Constitution.

Second, the United

States argued that, as the “world’s greatest military and economic power, more

than any other country the United States is expected to intervene to halt

humanitarian catastrophe around the world.”101 This unique position of the

U.S., government officials argued, makes U.S. personnel around the globe

“uniquely vulnerable” to malicious prosecutions by the ICC Prosecutor.102

Third, the U.S. was not satisfied with the language concerning the specific

reach of universal jurisdiction as outlined in the Rome Statute. The statute

allows for the ICC to have jurisdiction over any person, whether or not that

individual’s state is a member of the Court. The position of the U.S. is that

this is too broad a definition of universal jurisdiction, one that infringes

illegally according to international law on the sovereignty of those states

which choose not to become party to the ICC103.

India was also

expected to adopt a liberal interpretation and India did indeed adopt a liberal

interpretation, recognizing the existence of the international legal principle

of universal jurisdiction, but disagreeing with the interpretation of this

principle as laid out by the Rome Statute to the International Court of

Justice. Like the U.S., India had a number of specific justifications for its

disagreement with the Rome Statute. First, India seemed to express the

sentiment that it felt its concerns were not taken seriously enough during the

drafting of the Rome Statute.104 India believed that the expression of

universal jurisdiction in the Rome Statute was too broad in delineating the

situations which may be brought before the Court. India thus shared the

concerns of the other states that prosecutions may be brought before the Court

for political purposes.105 India was further concerned about the ability of the

Security Council to refer cases to the ICC in potential contravention of

international law.106 Further, India shared the reservations of the U.S. that

the Rome Statute’s power to prosecute nationals of non-party states was an

acceptable interpretation of the principle of universal jurisdiction.107

Finally, India, despite its own status as a nuclear state, was concerned about

the exclusion of the use of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass

destruction as a crime within the jurisdiction of the ICC.108 India’s

interpretation of universal jurisdiction encompasses the belief that use of

such weapons is a crime abhorrent to the international community as a whole.

In many ways, the

situation of India and its interpretation of the international legal principle

of universal jurisdiction is similar to the case of Turkey and its

interpretation of the international legal principle of anticipatory

intervention in self-defense. In both cases you have fairly new democracies

with legal institutions largely based on those of other states trying to

increase their presence in the international system while at the same time

maintaining their sense of national identity and sovereignty after many years

under the thumb of others. And just as was the case with Turkey in part four,

India has been reluctant to relinquish sovereignty over its laws to the

international realm. And while India might be expected to sign on be to

demonstrate its recognition of human rights and its desire to move into the top

echelon of states in the international power structure (reputational issues,

etc.), India has not adopted the traditional interpretation of universal

jurisdiction.

India, of the four

countries, also has the least to lose by signing on, given its minimal troop

presence in UN operations, etc. What India does have, however, is a common law

tradition which has developed out of a historical legal tradition comprising customary,

Hindu, and Islamic law. These traditional legal influences are still present in

the India tradition, even with the development of common law-style institutions

and constitution. The historical traditions have on Indian policymakers

apparently influences their understanding of the purpose of law, and makes the

notion of subjecting Indian citizens to law which is not steeped in these

traditions unthinkable.

This theory is also

buoyed by the historical caste system in India which, while no longer legally

valid, still permeates society. Under this system, those of the upper castes

cannot be brought to trial by those of the lower castes. This applies internationally

as well.

The United Kingdom

also met expectations, adopting a traditional rather than a liberal

interpretation of the international legal principle of universal jurisdiction.

The United Kingdom ratified the Rome Statute of the International Criminal

Court on October 4, 2001.109 While this may seem somewhat surprising given the

United Kingdom’s place as the origin of the common law tradition and the fact

that the U.K. regularly has troops participating in NATO and other coalition

operations110, the membership of the U.K. in the European Union has done much

to alter the tradition attributes of the state’s legal tradition.

Moreover, the U.K.,

for most of its long history, has not had a Bill of Rights, so concerns like

those of the U.S. do not apply. Also, the U.K. has already agreed to relinquish

its sovereignty over certain human rights issues and international crimes to regional

bodies – the ECJ and the ECHR – so its legal tradition is already accustomed to

such action. The member states of the European Union, in fact, are “accustomed

to external supervision and even adjudication of their human rights practices.

… The process of European integration has forced these states to accept to a

considerable degree the pooling of their sovereignty.”111 This results in a

very different perception of the impact membership in the ICC and adherence to

the Rome Statute’s conception of universal jurisdiction would have on the

state’s sovereignty. Due to its adherence to the Rome Statute, the U.K. is not

less sensitive to the sacrifice of sovereignty than some of its common law

counterparts.

Australia is the sole

case out of the twelve examined in this project which did not meet

expectations. As in chapter five in the case of sic utere,

based on the attributes of the Australian tradition, we would have expected

Australia to adopt a liberal interpretation of the principle of universal

jurisdiction in this case. As with the U.S., we would have expected this to

manifest itself in Australia’s not signing on to the Rome State of the

International Criminal Court However, Australia did accept the Rome Statute’s

interpretation of the principle of universal jurisdiction and ratified the Rome

Statute on July 1, 2002.112. This is perhaps the most surprising case because

in so many ways the Australia legal tradition and its historical development

are similar to that of the U.S.

There is, however,

one key difference: Australia does not have a Bill of Rights. In the case of

human rights protections outlined by the principle of universal jurisdiction in

the Rome Statute to the ICC, given Australia’s somewhat rocky history with the

protection of rights, the concerns over misuse of the international legal

process by politically-motivated actors was likely minimized when balanced

against the desire to demonstrate the country’s adherence to human rights

protections. Moreover, the lack of a concrete bill of rights, such as is found

in the United States, means that there were no conflicts similar to those found

in the U.S. discourse of constitutional protections of due process.113 In fact,

in recent years, it has been suggested that precisely because Australia lacks a

comprehensive charter of rights, the country’s litigants and lawyers are

“turning to international law in the quest for a peg on which to hang arguments

designed to persuade Australian courts that part of international jurisprudence

has been, or should be, incorporated by judicial decision.”114 This particular

attitude towards human rights law originating from the attributes of the

Australian legal tradition, and differing from those of the other three states,

helps to explain why Australia adopted the method of interpretation they did in

the case of the Rome Statute of International Criminal Court, rather than a

more liberal interpretation as expected.

(B) How this is better than existing theories (both

those which focus on more general descriptions (common law/civil law etc.) and

the realist and NLI theories.

The subject of this

above research – that legal tradition explains the interpretations adopted by

states towards international law – correctly predicts the interpretations

adopted in three of the four states examined above, and provides an explanation

for the missed prediction in the case of the fourth state. This then provides a

much more complete picture of the influence of legal tradition on state

interpretation of the international legal principle of universal jurisdiction

as codified in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court than other

international relations theories. First, those few works which do focus on

legal tradition, but only as the broadest of categories, such as common law,

would only have correctly predicted the outcomes for two of the four countries

in this chapter. More importantly, by focusing only on the common

characteristics among the common law states, these theories would have been

unable to provide a satisfactory explanation as to why two of the four states

defied expectations.

Performing even

worse, would have likely been more traditional international relations

explanations, which don’t consider legal tradition at all. Theories centered on

power and interests would have suggested, as outlined above, that the concept

of universal jurisdiction outlined in the Rome Statute of the ICC would have

only succeeded in becoming an accepted definition if supported by the most

powerful states. Given many of the most powerful states in the world – the

U.S., Russia, China, India, Australia – did not sign on, these theories would

predict none of the four states in this study would have joined the ICC. They

would have been wrong on all four counts.

Moreover,

interest-based theories would have suggested that signing on to an

international treaty such as the Rome Statute, which requires states to

relinquish a small amount of sovereignty is not in the state’s interests,

particular when perceived assistance with some collective action problem is

minimal due to the nature of the institution.

Moreover, as

described in the context of both part 3 and 4, however, this conception of interests only focuses

on the short-term material interests of a state. An examination of the

long-term interest of the state would lead to the conclusion that becoming a

party to the Rome Statute is actually more beneficial for the state because the

state then has the opportunity to participate in the workings of the ICC,

including drafting the Court’s procedures, selecting the prosecutor and the

justices, and participating in discussion over which cases should be heard115.

Particularly once it became clear that the Rome Statute was going to receive

the 60 ratifications required to enter into effect, it becomes in the state’s

interests to sign on to the Court. States do not tend to think in the

long-term, however, and in considering short term interests this theory would

not have successful predicted the outcomes either.

Certainly

consideration of interests mattered in each of the interpretations states made,

but as suggested by the theory of this project, the extent to which the

interests can be considered varies depending on the attributes of the legal

tradition. In the case of the U.K., for example, while protection of the

state’s numerous soldiers engaged in military actions abroad and protection of

U.K. citizens from politically-motivated prosecutions was likely as relevant to

the decision-makers in the United Kingdom as it was in any of the other three

states examined, the influence on its legal tradition and perceptions of the

appropriate course of action for the good of the community wielded by the

European Union mitigated the extent to which the U.K. policy-makers were able

to consider these interests.

Moreover, in this

specific case, since each of the four states examined is involved in sending

its military personnel to other countries – both on UN peace-keeping missions

and in relation to other armed conflicts – each of these states has the

potential for concern that its own military will be subject to prosecution by

the ICC for acts committed in the course of these actions, as well as a concern

over the potential for politically-motivated prosecutions. This is a very real

concern, for all four states116, as each has been (or is) involved in

situations in which their presence is unpopular. For example, India has troops

in Sierra Leone acting as peacekeepers under the auspices of the United

Nations.

The Commander in

Sierra Leone is an Indian national named Major General Vijay Kumar Jetley, who has come under fire for actions perceived by

other states as invalid, despite the highest praise from former UN Secretary