As we have seen so far variations in the relative

scope of three social subsystems are a necessary condition for change: Popular innovation

by norms entrepreneurs is a sufficient condition for a change in sovereign

principles and will determine when systems change occur. Economic efficiency

and coercive power might explain the predominance of one type of unit over

another it never provides a compelling logic for why certain units proliferate

and when those units will proliferate. And conflicts between growing and

contracting social systems make certain types of sovereignty more or less

efficient and in turn dictate the structure of the international system. The

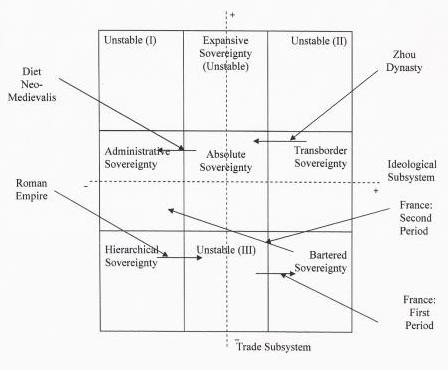

theory can be summarized in three parts:

1) World order is determined by the dominant type of

sovereignty.

2) Sovereign principles are efficient and stable when

they mediate the conflicts between the spatial limits of the underlying

subsystems.

3) Therefore unit types and international order vary

when the sovereign principles become inefficient and norms entrepreneurs begin

to experiment with alternatives.

Formulated in this way it provides a general sense of

the types of units that are likely to prevail in a variety of circumstances and

a more specific understanding of why sovereign principles form in the way that

they do.

For example, in the beginning, according to the Old

Testament, there was a formless void. In international relations theory, the

dominant way of thinking treats the modern world as equally formless. Yet

sovereign principles are undeniably present and mustcome

from somewhere. Agency is a central issue in this problem. Who creates

sovereign principles? It is not as if competing social subsystems create these

hierarchies out of thin air. The subsystems themselves have no agency; it is

the people involved in each that ultimately must create these sovereign

principles. In this way it is no more and no less than foresight and luck that

lead some individuals to create a sovereign principle.

In Rome ’s case shortly after their initial victories

over Latium they arrived at a crossroads. Had Lucius Camillus not spoken up it

is impossible to say whether Rome would have become dominant. Had they pursued

the other option on the table, eliminating the Latins, would their empire have

ever been stable? Similarly in France, had Charlemagne or Henry IV been less

effective or innovative there are many reasons to believe that the unstable

periods that they were born into might have persisted. It is the precarious

nature of this genesis and the unfortunate unpredictability that make this so

discomfiting to most political scientists. The central role of these norms

entrepreneurs in the genesis of sovereign principles during these periods is of

central importance. Individual actors responding to a common problem arrive at

different solutions. While Roman or French or Qin military and economic prowess

may explain their overall success it does not explain the longevity of their

success nor the manner of that success. Norms entrepreneurs do however. There

is nothing mysterious or curious about this genesis and it is, in fact,

consistent with the existing literature on the evolution of rules and norms.

Why did any of these figures attempt to create new systems or rule when they

did, and why were they successful?

Augustus’ decision to contract the military and limit

expansion was politically expedient at the time, but compounded with later

decisions to fortify the limes to stymie the security subsystem and eventually

contract it. Similarly, Duke Zheng’s creation of the ba

system compounded with Sun Tzu’s strategy of building massive infantry armies

to deter war and to ultimately expand the security subsystem while the

ideological subsystem did not experience a concomitant expansion. None of these

policies are objectionable in and of themselves, but over time they have the

unintended consequence of debilitating the existing sovereign principles.

Hierarchical sovereignty was possible precisely because of Roman hubris in the

same way that transborder sovereignty was possible because of the inherent

limitations of individual Zhou states. On the first account in each of these

cases we find that elites and norms entrepreneurs are quite aware of the

principles of rule that guide their polities. In some ways Tacitus, through the

mouth of Galgacus, is speaking directly to Lucius

Camillus and Livy when he comments, “They make a solitude and call it peace.”

Over centuries of Roman rule, through wars and civil wars and coups, the elites

found themselves guided by the same set of preferences and priorities. It is

significant that those preferences change profoundly right at the very end of

the Western Empire.

The second issue, the resiliency of these sovereign

principles, is reinforced by the continuity of these narratives. Sovereign

principles are successful over time precisely because they are able to

withstand the immediate consequences of shortsighted policies. Conversely,

sovereign principles become entrenched quickly when the principles are

insightful and well-conceived. The principles encompassed in the Edict of

Nantes were not only political expedient in resolving the immediate conflict

between Protestants and Catholics in France, but as we see subsequently in the

rule of Louis XIV useful beyond their immediate intended goal. The Edict of

Nantes created relative peace in France and began to unite the state when other

contending polities were still deeply fragmented. But its true power was in the

principle of absolutism that it embodied. The norms entrepreneurs that succeed

seem to be the ones that solve an immediate problem with a long-term solution.

Long-term solutions are often pragmatic about the limits of the ruler’s power

given the existing conflicts between the subsystems. King Wang’s imprint upon

the Zhou Dynasty established the Mandate of Heaven at the same time that it

recognized the material limitations of its feudal system. Each fief was strong

enough to assert itself if it did not buy into the essential legitimacy of the

mandate.

The transborder sovereignty of the Zhou Dynasty played

to the strengths of the Zhou rulers. Those strengths, we have demonstrated, are

determined by the differential growth and contraction of the various subsystems

relative to each other. The degeneration of sovereign principles in each of

these cases is thus mostly attributable to either encouraging changes in the

relative scope of these subsystems through various policy changes or ignoring

the sovereign principle in the first place. The revolutionary moments in each

of these case studies tend to reinforce the existing research. The periods of

instability and experimentation may be prolonged as they were in the European

and Chinese cases, or quite short as they were in the Roman case. Regardless

these cases studies seem to support two conclusions about the international

system:

1) Sovereign principles are resilient and domestic

policy or institutional changes are not a sufficient condition for change in

the international order.

2) Subsystems are highly fluid, but changes in the

principles or patterns of the subsystems are not a sufficient condition for

change in the international order.

Thus revolutionary change on this scale is very difficult to achieve and only

happens intermittently. The specific shifts as seen next can occur in a number

of ways:

The various theories of global governance and the

evolution of the international system have been mainly concerned with more

practical issues such as the democratic deficit, or a nascent American imperialism,

or as Robert Kaplan has termed it, ‘the coming anarchy.’ (Robert Kaplan, The

Coming Anarchy: How scarcity, crime, overpopulation, tribalism, and disease are

rapidly destroying the social fabric of our planet. The Atlantic Monthly,

February, 1994, 44 – 76).

In each case the concern is that mundane problems of

globalization will continue to manifest themselves and irrevocably undermine

the edifice of the Westphalian system. Taken as face value these concerns seem

at once legitimate and obscure. For example, it is not entirely clear how

increasing instability in Africa might ultimately undermine the stable zone of

peace that exists among American, European, and East Asian countries. Nor is it

clear that a democratic deficit exists or is actually problematic for sovereign

states. In addressing the future course of the international system we must

move beyond various specific challenges to the international system and deal

with the spatial dynamics of the subsystems. If American imperialism is the

dominant story of the last 60 years then perhaps we ought to expect a move

towards hierarchical sovereignty. Rather than addressing the potential changes

in the dependent variable, which may be obscure or open to multiple

interpretations, it seems more fruitful to consider such a possibility in terms

of the independent variable. This study has shown that any term, like

feudalism, can have multiple meanings and represent distinct sovereign

principles. It is thus entirely possible that we could speak of a nascent American

imperial that represents the status quo. Most claims about the evolving

security subsystem tend in two directions. In one direction lay the claims

about American military preponderance. In the other direction lay various

claims regarding asymmetric warfare, the democratic peace, and the obsolescence

of war. During the Cold War the US Congress structured military appropriations

around the goal of being able to fight two Major Regional Contingencies (MRCs).

This strategy was taken to mean major wars on two fronts in two different parts

of the world. Military preponderance became a primary goal of the

appropriations and strategizing process. One requirement for this strategy to

be effective has been the use of basing agreements and bilateral Status of Forces

Agreements (SOFAs). Judged simply by military expenditure it are American

military bases that are most advanced, most adept military in the world. The US

spends more on the military than the next 15 countries combined. (See (SIPRI),

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2006, see also: http://www.sipri.org/contents/milap/milex/mex_data_index.html).

The closest contenders, Russia and China, either lack

a blue-water navy or lack the capacity to use it. Judged simply on geopolitical

influence one is tempted to claim that the scope of the American security

subsystem is nearly global. (See Frank Umbach, The

Maritime Strategy of Russia: The Gap Between Great Sea Power Ambitions and

Economic-Military Realities. In Maritime Strategies in Asia, edited by J.

Schwarz, W. Herrmann and H.-F. Seller. Bangkok 2002).

However this tends to miss a number of important

qualifying concerns. Chief among these are the extent to which MRCs have been

replaced by operations other than war (OOTWs) and the increasing importance of

asymmetric warfare. Asymmetric warfare refers to the use of unorthodox methods

in battle. Thus we arrive at a paradox; it seems as if American military power

is nearly global in scope, but this scope is far from absolute and does not

create any exclusive zone of peace. The capacity to create an expanding

American zone or peace is actually far more limited than the American network

or bases might suggest. Do we judge the security subsystem based on the first

or the second criteria? Given this conflict it seems as if the security

subsystem is more suggestive of a nebulous frontier, as the Roman limes were,

than of an overt delimitation of American power. The American military can

exert its influence everywhere, but it may not be able to dominate anywhere.

(See John E. Mueller, The remnants of war. Cornell University Press, 2004).

Thus in the case of the until now powerful USA, we

cannot take the network of American bases to be an absolute proxy for the

geographical scope of the American security subsystem. At the same time, the

social hierarchies that exist reinforce the basic notion that American hard

power is more pervasive than bases themselves. In discussing the subsystems as

they exist today it is necessary to move beyond the obvious indicators of their

existence such as bases and towards evidence of their role structure. In this

vein American military power secures outcomes and defines hierarchies in a

diverse set of circumstances. However, granting both the extensiveness of the

role structure provided by the American security subsystem and the actual

limitations of American power one is tempted to claim that the American

security subsystem is contracting.

One can furthermore, not assume that incidents that

seem to demonstrate the weakness of a hegemon actually reflect any true change

in the hegemon’s power. The most that can be said than is that the US security

subsystem is stagnating. (See for example Joseph S. Nye, The paradox of

American power: why the world's only superpower can't go it alone, Oxford

University Press 2002 and Charles Kupchan, The

end of the American era: U.S. foreign policy and the geopolitics of the

twenty-first century, 2002).

As the United States realizes a growing inability to

dictate outcomes on the periphery, as evidenced by nuclear proliferation, it is

also implicitly legitimizing the existence of non-state armies. The second

largest coalition force in Iraq are PMCs. The scope of the security subsystem

is stagnating and new innovations, such as PMCs, are becoming a more popular

alternative to this security subsystem. (A. Leander, 2005. The market for force

and public security: The destabilizing consequences of private military

companies. Journal of Peace Research, 2005, 42 (5): 605-622).

Another argument has to be that the telecommunication

revolution has brought everyone in the world in more direct contact with each

other and as such has put diverse peoples on a more even footing with each

other. The general principle of market capitalism that structures this subsystem

is focused mainly on capital mobility. Recent conflicts have begun to force

revisionist thinking, but the general framework of agreements that structure

the trade subsystem have favored capital mobility over labor mobility, and as

strange as it may sound, land mobility. Labor mobility has increased

substantially over the course of this globalizing period, but much of it has

been unwanted or undocumented or unexpectedly permanent. Every developed

country sees itself as having an immigration problem. Traditional immigrant

states such as the United State, Canada, and Australia have managed their

problem more effectively than others, but still have massive unresolved debates

over the nature of labor mobility. Similar debates of capital mobility are more

restrained and policymakers are far less inclined to limit capital mobility.

The foreign acquisition of land is less of a problem all around. Numerous

scholars have argued that globalization and capital mobility have confounded

the ability of states to actually control this increased level of commerce or

more importantly to tax the profits from it. (Sungur Savran, Globalisation and the new

World Order: The New Dynamics of Imperialism and War. In The Politics of

empire: globalisation in crisis, edited by A. Freeman

and B. Kagarlitsky. London, 2004, Pg. 128).

The increased scope of the trade subsystem has united

economically diverse portions of the international system. Increased

competition between these diverse states and groups has created downward

pressure on social welfare systems in developed and developing countries alike.

R. B. Hall has shown how the Asian miracle was gradually replaced by the Asian

failure after the crisis of 1997 and 1998 when in fact it was a more systemic

failure in general. The financial austerity paradigm that has been gaining

advocacy after World War II, particularly after the collapse of Bretton Woods

in 1974, has generally painted the success of the Asian tigers in shades of

free market superiority, and export-led growth. The truth of the matter is not

nearly this black and white. Nonetheless the agreements contained in the

Uruguay Round negotiations of the WTO and the agreements being hashed out in

ongoing Doha Round negotiations are creating more homogeneity not less, and

more free markets not fewer. The struggle between providing a minimal set of

welfare benefits in developing countries and maintaining sufficient financial

solvency has hamstrung many of these developing nations, but they almost always

choose to go towards free markets, not away from them. The level of austerity

required by IMF conditionality and World Bank loans has been softened, but it

becoming more pervasive all the same. The trade subsystem continues to grow in

scope at a fairly steady pace; expansion of the freemarket

hierarchy has continued with few setbacks. (R. B. Hall, The discursive

demolition of the Asian development model. International Studies Quarterly,

2003, 47 (1):71-99).

But while Romanization created a direct linkage

through access to citizenship through submission. Americanization creates a

more diluted linkage through each individual state and through the state to the

international order. Just as in the Roman case this creates some inherent

contradictions. The priority placed on individual rights sometimes conflicts

with the priority placed on groups rights through self-determination. Popular

culture, as in Roman times, enables individual and group expression at the cost

of being unable to reject the popular culture itself. In the same way Americanization

accepts all modifications to it, but it is more difficult to reject

Americanization itself.

For updates

click homepage here