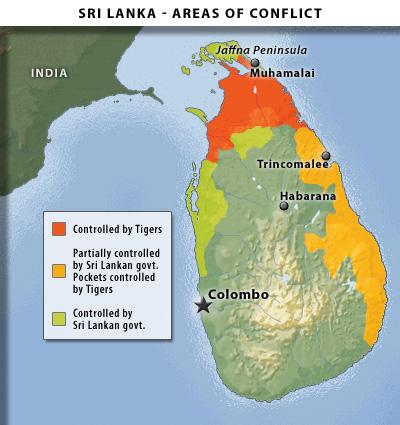

During the ongoing conflict, both sides have dangled peace talks as a military tactic, proposing talks when they feel too much pressure from the other. The fighting ostensibly stops during the ensuing discussions, allowing the proposing side time to regroup and prepare for the next round of fighting. On Sept. 27, reclusive Tiger leader Velupillai Prabhakaran proposed talks with Colombo as a way to salvage the 2002 cease-fire agreement. The Sri Lankan government initially declined to commit to the talks, indicating its belief that the offer was disingenuous. Colombo finally agreed to the talks Oct. 4, though the debate rages on over the logistics. Meanwhile, believing the Tigers were weak, the Sri Lankan army continued its offensive on the Jaffna Peninsula. Perhaps encouraged by its recent successes against the Tigers in other parts of the country, however, the Sri Lankan military underestimated its enemy's strength on Jaffna and failed to realize the threat to its personnel at Habarana.

Despite their recent successes, the Tigers remain on the run. Although the rebels routed the Sri Lankan army in Jaffna, the military's offensives, and its efforts to interdict Tiger supplies by sea, have badly hurt the Tigers. There are indications that the group's arms are drying up and that it is getting desperate for ammunition. Suspending the fighting during peace talks would enable the Tigers to address these problems.

Just south of Sri Lanka's territorial waters are major international shipping routes connecting Southeast Asia with the Middle East. Among other shipping, oil tankers run from Persian Gulf terminals to buyers in Asia via the Indian Ocean. Peace in Sri Lanka would create many investment opportunities taking advantage of Sri Lanka's valuable location. Disturbingly for Sri Lanka, the Tigers' naval capability has expanded to the extent that the group now demands international recognition for the "Sea Tigers" on par with that of the Sri Lankan Navy. The Sea Tigers claim to have sunk more than 30 Sri Lankan naval vessels.

The U.S. Marine Corps will participate in unprecedented exercises with the Sri Lankan navy at the end of October, deploying more than 1,000 Marines and large support ships to drill with the Sri Lankan armed forces on amphibious and counterinsurgency operations. Coincidentally, the exercise is occurring on beaches in Hambantota -- precisely where the Chinese are planning to build oil and bunker facilities.

India's stature and influence in the international system continues to grow, and nearby Pakistan and Bangladesh battle Islamist militancy. Thus the United States military understands the utility of Sri Lanka's proximity to these countries. In 2002, Washington and Colombo signed a broad defense agreement under which Sri Lanka allowed U.S. ships to dock and refuel in domestic ports in exchange for U.S. military training and equipment. U.S. warships involved in Afghan operations, such as the USS Sides, used the port of Colombo under the deal.

The port of Trincomalee, on the northeastern coast of Sri Lanka, also stands out as strategically significant. In recent weeks, the port town saw widespread attacks and retaliation between the Tigers and Sri Lankan forces. If peace were somehow established, Trincomalee would certainly rank on the U.S. military's wish list, being one of the deepest natural ports in the world. While Sri Lanka extracts some geopolitical utility from its location, much more could be achieved if a political resolution between the Tamils and the Sri Lankan government were not so inconceivable.

Sri Lanka's vast neighbor, India, has a vocal and electorally important ethnic Tamil constituency that sympathizes with the Tigers' cause. While India can never be seen as publicly sympathetic to militant group responsible for the assassination of former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, domestic politics force New Delhi to avoid being seen as pro-Sinhalese (and thus anti-Tamil). The Indians also have an interest in keeping Sri Lanka in a state of contained chaos so long as an untenable refugee crisis does not overwhelm India.

China and Pakistan, meanwhile, have recognized the utility of assisting the Sri Lankan government in its fight with the Tigers as a tool to edge their way into India's backyard.

Whatever Washington's reasons for the exercises, the maneuvers could not happen without India's permission. Though New Delhi is not nearly the geopolitical powerhouse that Washington is, the United States has anointed India as its junior partner in the Indian Ocean. The United States -- and other members of the Sri Lankan Donors Group, which assists with post-tsunami rebuilding and brokers peace talks -- traditionally consults with India on all decisions related to Colombo.

It is precisely this interest in regional pre-eminence that led India to give the go-ahead for U.S. forces to participate in a major training exercise geared toward fighting the Tamil insurgency. After all, India cannot risk offending its own sizable Tamil minority if there is not a substantial reward involved. In this case, the reward is the chance to send a targeted message to one particular country with the U.S.-Sri Lankan exercises: China.

The much-ballyhooed Indo-Chinese rivalry is not nearly as heated as many believe. Significant geographical factors -- such as the Himalayan Mountains and thousands of miles of jungle -- prevent India and China from having any real disputes. However, the countries share a common naval frontier near the Strait of Malacca and Singapore. The United States, with Indian assistance, intends to maintain the Indian Ocean as its own strategic waterway. China's intrusion into the area by building ports at Gwadar in Pakistan, in Myanmar and now possibly in Bangladesh irks New Delhi. Thus, it is no coincidence that the exact area of the U.S.-Sri Lankan exercises is Hambantota, the very harbor that China announced it would begin developing for Colombo in 2005.

There are also indications that the relationship between India and China is becoming increasingly frayed. China was likely the major stumbling block to India's Shashi Tharoor becoming U.N. secretary-general, and India has been blocking Chinese investments in infrastructure due to security concerns. India, already deeply rooted in its protectionist traditions, has focused its rising economic nationalist agenda primarily on Chinese assets. For example, Hong Kong-based Hutchison Ports Holdings has faced delays in obtaining security clearances from New Delhi, and, as a result, has been unable to commence operations on port projects at Mumbai and Chennai.

Chinese President Hu Jintao's upcoming visit, during India's National Day, will give both sides a chance to mend some fences, but the U.S. Marine Corps exercises reveal a deeper geopolitical reality: The United States and India will not tolerate Chinese expansion, especially into the Indian Ocean.