The 1947 French

Cheval-Blanc is widely recognized as one of the most expensive wines, but it is

not the only one. According to a report last month (May 2021) Château

Lafite-Rothschild 1896 at $233,000, Shipwrecked 1907 Heidsieck at $275,000,

1947 Cheval Blanc at $304,375, 1945 Mouton-Rothschild at $310,000, Screaming

Eagle Cabernet Sauvignon 1992 at $500,000,1945 Romanee-Conti

at $558,000. Whereby a bottle of wine aged in space could sell for $1

million.

Christie’s is

selling a bottle of

Pétrus 2000 that

was aged for 14 months aboard the International Space Station (ISS) before

returning to Earth in January. And the British auction house estimates will

ultimately fetch a price “in the region

of $1 million.”

That would make the

space-aged vintage the most expensive bottle of wine ever sold. (The current

record for a single bottle of wine came in 2018, when anonymous buyers paid $558,000 for a bottle of 1945 Romanee-Conti

French Burgandy, sold by Sotheby’s.)

But do such expensive wines really taste all that much

better than cheaper wines?

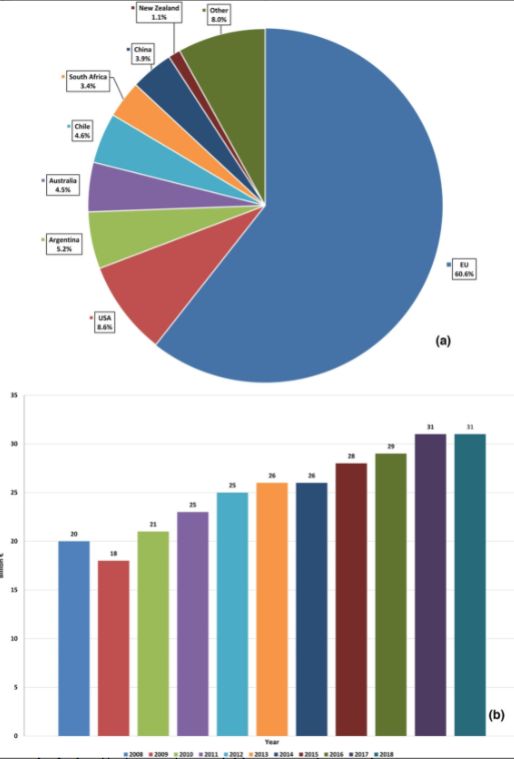

Let us start with a

look at the wine trade which in 2018 reached €31 billion.

The wine report

Legally, wine is the

alcoholic beverage obtained from the fermentation of the juice of freshly

gathered grapes. It may contain a few other things - some sulphur

to preserve it and sugar added to the must to a'djust

the alcohol content - but these additives are properly policed by the relevant

authorities.

When you are buying a

bottle of wine however, you can be confident that it really is fermented grape

juice and that it really does contain the amount of alcohol stated on the

label. It has been said that the wine commercially produced today (January 2008)

is a far more pure and reliable product than that produced before (discounting

the anti-insecticides that is). In the past, adulteration of wine was the rule;

now it is the exception. With bread, the reverse is true, and as with wine in

the past, we are no longer sure what bread is, never mind whether it has been

falsified.

But how for example

did bread become (generally) so bad and wine (relatively) so good? Part of the

difference lies in the fact that wine is a much less natural product than

bread. Whereas bread is cooked, wine is manufactured; the one is (potentially)

ruined by large-scale modern industry whereas the other is (potentially)

improved by it. Good wine is the result of a complex interaction between man

and the environment, and for a long time man was less than expert at his side

of the bargain, making mistakes which he could only rectify by poisoning his

own product in order to cover them up.

For all their odes to

wine jars and apostrophes to wine-dark seas, the Greeks and Romans made some

badly corrupted wines. Pliny the Elder was complaining about it in the first

century AD. 'So many poisons', he wrote in his Natural History, 'are employed to

force wine to suit our taste - and we are surprised that it is not wholesome!'

Wine-making was an imprecise art, and ancient wine-makers were much less

skilled in monitoring the various stages of manufacture to achieve the taste

they desired than their modern equivalents. If all the elements came together -

a luscious harvest of grapes and accurate fermentation - ancient wine might

well have been delicious. Often, though, wine came out wrong and needed to be

'adjusted' after the event. So, in Africa, said Pliny, rough wines might be

softened with gypsum and, 'in some parts of the country, with lime'. The Greeks

on the other hand, feared blandness in wines rather than roughness and they

enlivened the smoothness of their wines with potter's earth or marble dust or

salt or sea-water, while in some parts of Italy they use resinous pitch for

this purpose and it is the general practice both there and in the neighboring

provinces to season must with resin; in some places they use the lees of older

wine or else vinegar for seasoning.

Some of the additions

for enhancing the wine's flavor were fairly harmless. Commonest was honey,

often added in prodigious quantities - as much as half and half - suggesting

that unsweetened wine must often have been a mouth-puckeringly sour drink. The Gauls apparently were fond of adding herbs, such as thyme

or rosemary. The Greeks added rose petals, violets or mint. Pliny mentions such

strange additions as asparagus, rue, sorb apples, mulberries, Syrian carob pods

(a bit like chocolate), juniper berries, turnips, roots of squills, cassia,

cinnamon, saffron. It is hard to know which of these were adulterations proper

and which were simply culinary innovations. We do not believe we adulterate

wine when we add cinnamon quills, cloves, orange peel and sugar to 'mull' it at

Christmas time (though the quality of the wine can often do with concealing).

On the other hand, some of these ancient flavorings were clearly intended to

deceive. The Roman farming writer Columella recommended various artificial

flavorings but advised wine-sellers not to advertise the fact 'for that scares

the buyer off.

Other ancient wine

additives had a more practical purpose. The great problem with wine was that it

went off so quickly. Most Roman wine was essentially alcoholic fruit juice.

There were exceptions to this - the poet Juvenal writes of vintage wine laid down

in its bottle for centuries, since the time when Consuls had long hair - but

these more mature wines were just this: exceptions.

Beaujolais Nouveau is

well aged by comparison with most ancient Roman wines. We can get some idea of

how quickly ancient wine deteriorated from the fact that the jurist Ulpian,

writing in the third century AD, described 'old wine' as wine made the previous

year. Anything which could make the wine keep longer in the Mediterranean

climate was seized upon, with too little thought for the effect it might have

on the wine's wholesomeness. This was the main reason that so many wines,

Greek wines especially, were resinated - the ancient

counterparts of modern retsina. The earthenware amphorae in which wines were

kept were often porous, letting air in and oxidizing the wine. Wine-makers

found that the wine kept better if the inside of the jar was coated with resin;

and better still if a little resin was added to the wine " itself along

with the must, either in powdered form or as a sticky liquid. Eventually,

drinkers became connoisseurs of different kinds of resins - the resin of

Syrians said to resemble Attic honey - but resin's primary purpose was

preservation; drinking a glass of inferior retsina can still feel a little like

being pickled in Cuprinol.

Preservation was also

the point of adding seawater - salt is a preservative - though it must have

made for a repulsive drink. Pliny complained that wines made with seawater were

'particularly injurious to the stomach, nerves and bladder'. Nothing like as

injurious, however, as a still more popular preservative, namely lead, which

Pliny saw as harmless; and he was not alone in this belief. The Romans thought

that lead was wonderful for wine. Lead ions inhibit the growth of living

organisms, so lead delayed the point at which wine turned into vinegar and

generally made it less apt to spoil. What is less well known - because we do

everything we can not to consume it now - is that lead is delicious. Those

Victorian children gnawing on their lead pencils and chewing on their lead

soldiers were not just playing out some Freudian oral fixation, they were also

satisfying a craving for sweetness. The Romans swore by lead to correct a sour

wine, making it sweeter. This was especially the case if the lead was added in

the form of sapa or difrutum,

a concentrated grape juice or must boiled down in a lead vessel.

Writing as a

landowner in the first century AD, Columella noted that 'Some allow a quarter

of the must to boil away after pouring it into leaden pots, some a third' but

that 'if one lets half of it boil away, it becomes undeniably a better sapa' - and one with a higher lead content. The farming

writer Cato recommended using a fortieth part of this deadly reduction during

wine-making. He would surely never have done so, had he realized that lead was

a poison, capable of causing headache, fatigue and fever; sterility; loss of

appetite; severe constipation and unbearable colic pains; loss of speech,

deafness, blindness, paralysis, loss of control of the extremities- and

eventually death. Leaded wine must have had terrible effects on the Romans one

historian has suggested that endemic lead disease may have been one reason why

so many wealthy Romans were sterile - yet they continued to drink it in the

belief that it was good for their health.

What made lead a

poison was that its effects are cumulative. Most of the body's absorbed lead is

stored in the skeleton where it builds up over many years. Unlike food

poisoning, which quickly affects all those who eat a sink meal, the symptoms of

lead poisoning build up variably and gradually. So the use of lead in wine

continued long after the Romans, down into modern times, reflecting the fact

that without lead, or some other preservative, 'most wine was so unstable that

it was likely to deteriorate and go bad within a year of being made, even when

it was not shipped over long distances and exposed to rough handling and

fluctuating temperatures'. Sometimes there would be a mini-epidemic of wine-

induced lead poisoning, especially after a cold summer when the sourness of the

grapes encouraged wine-makers to overdo the lead. This disease came to be known

as the colic of Poitou or coliea Pietonum,

because the citizens of that French town had suffered an especially bad

epidemic. Still the connection wasn't made between the colic symptoms - of

severe abdominal pain, weakness and nausea - and the lead. Doctors were more

apt to blame the sourness of the wine than the lead which had been used to

counteract the sourness.

It was only late in

the day, at the end of the seventeenth century, that the danger of lead in wine

was spotted, by a German medic called Eberhard Gockel, city physician of Ulm in

the BadenWurttemberg region. At that time, lead was

still a common addition to wine, though no longer as sapa.

Now, the lead additive usually took the form of litharge - a foam or 'spume'

produced during the refining of lead - or sometimes Bleiweiss (lead oxide) or

ceruse (lead carbonate). How did wine-makers get away with these deadly

additions? There had been plenty of laws against the adulteration of wine. In

1487 the city of Ulm had passed a law requiring every innkeeper to swear that

his wines were pure and that neither he nor his wife nor his servants had added

any of a list of additives which included Bleiweiss. Ten years later, an

imperial edict forbade various wine additives including ceruse. Yet these laws

were widely flouted. Penalties for doctoring wines were 'surprisingly lenient'.

In the fifteenth century, German wine adulterers were punished by money fines

plus public shaming and their wine was poured into the river. This was pardy because legislators did not realize the effects of

lead on the Ruman body; oni\.e they did, several German cities issued laws

specifically forbidding the use of litharge in wine with stringent penalties -

imprisonment and death - for those who broke the law.

It was by accident

that Gockel discovered the evils in the habit of 'correcting' wines with lead.

Over the Christmas holidays in 1694 - a time when festive cheer may have

encouraged some of the monks to indulge a little too heartily - the prelate of

the Teutonic Order of the Knights of Ulm and several of his monks developed

colic. Gockel was summoned. His first impulse was to check the wells and the

kitchen, neither of which had anything amiss. Gockel noticed that all the monks

who had not drunk wine had been spared the colic. Then, on one of his visits to

the ailing monks, he accepted a glass of wine and soon found himself feverish

and with chronic colic pain. after much investigation, he eventually tracked

down the recipe for this wine from a dealer near Goppingen, and found that it

contained litharge. At once, lead became the prime suspect. To make sure,

Gockel did some experiments. He took the 'worst and sourest wine' he could find

and by adding litharge managed to convert it into the 'best and loveliest of

wines' - the word he used was susselectenlieblichen,

one of those untranslatable German words, conveying a zenith of delectable

sweetness. Loveliest except for the fact that it caused horrific stomach aches.

Gockel's discovery

did not entirely eliminate lead from alcoholic drinks, however. In the late

eighteenth century, there was wide incidence in the English county of Devon of

'Devonshire colic' the result of lead poisoning from cider. Opinion differed as

to how the lead got there. In 1767 and 1768 George Baker published articles

arguing that the cider was contaminated by lead in cider presses. In 1778,

however, James Hardy insisted that it was not the presses that were to blame

but the lead-glazed earthenware from which the poor of Devon drank their hard

apple cider. The acid in the cider dissolved some of the lead in the glaze.

This explained why the poor were the most susceptible to Devonshire colic,

since they were the ones who used earthenware, while the rich drank out of

safer vessels made of glass and stone.

This lead poisoning

was accidental. Similar problems arose when wine bottles were cleaned with lead

shot. But the deliberate addition of lead to wine carried on too. In 1750, the

tax inspectors of France were 'astonished' by the huge volume of spoiled wine -

vin gate being brought into Paris; this inferior wine was used, perfectly

legally, to make vinegar. In this case, however, a number of wine merchants had

registered themselves as vinegar merchants in order to have access to this

cheap vinegary wine, which they touched up with litharge and then sold,

presumably at a great profit, as real wine.

Lead poisoning and wine falsification

Still more blatantly,

a book of 1795 called valuable Secrets Concerning the Arts and Trades

recommended sweetening “turned wine” - in other words, wine which had turned

acid - with a 'quarter of a pint of good wine vinegar saturated with Litharge'.

It makes you wonder

how such attitudes could persist, so long after lead had been proved a poison.

Frederick Accum answered this question in his

'Treatise on Adulterations of 1820. Lead continued to be added to wine, he

argued, because 'there appears no other method known of rapidly recovering ropy

wines'. As for the moral dimension, Wine merchants persuade themselves that the

minute quantity of lead employed for that purpose is perfectly harmless and

that no atom of lead remains in the wine. Chemical analysis proves the

contrary; and the practice of clarifying spoiled white wines by means of lead,

must be pronounced as highly deleterious.

To Accum, the vintner or wine dealer who “practises

this dangerous sophistication, adds the crime of murder to that of fraud, and

deliberately scatters the seeds of disease and death among those consumers who

contribute to his emolument.”

Accum's publicity probably contributed to the decline in the

use of lead in wine. It was also harder to doctor wines with lead once reliable

chemical tests were developed for its detection. In 1818 the French scientist

Mathieu Joseph Bonaventure Orflia (1787-1853) listed

no fewer than nine different tests for wines adulterated with lead; for

example, 'they scarcely redden the tincture of turns ole because the acid which

they naturally contain is saturated by the oxide of lead'.

But still the dosing

and doctoring of wine continued, In manifold forms. Winemaking was an art which

liked to shroud itself in mystery, and the trade secrets being hidden were

often criminal. A Renaissance critic complained that the vintner was “ a kind of

Negromancer, for at midnight when all men are

in bed, then he falls to his charms and spells, so that he tumbles one hogshead

into another and can make a cup of Claret that has lost its colour

to look high with a dash of red wine at his pleasure.”

In strikingly Similar

terms, more than a century on, in the English, Tatler magazine of 9 February

1710, Addison observed that: There is, in this city, a certain fraternity of

chemical operators, who work underground in holes, caverns and dark retirements,

to conceal their mysteries from the eyes and observation of mankind. These

subterraneous philosophers are daily employed in the transmutation of liquors,

and by the power of magical drugs and incantations, raising under the streets

of London the choicest products of the hills and valleys of France. They can

squeeze Bordeaux out of the sloe, and draw Champagne from an apple.

These “subterraneous

philosophers”, also known as “wine brewers” because they could brew up wine

from virtually anything, had their counterparts all over Europe. Sicilian

growers in the nineteenth century were notorious for adding chalk to many

wines, not only to preserve them, but to speed up clarification and improve the

wine's colour. This chalked wine - vino gessato - became so common that foreign buyers lost trust

in Sicilian wine and were made to pay a premium for non-chalked wine - in other

words, forced to pay extra for something which should have been standard all

along.

French wine was

regularly falsified too. During the 1870s when French vineyards were struck by

vine blight, there was a 'notable increase in dishonesty'. To maximize yields,

wine-makers started to make watery brews from the second, third and even fourth

pressings of grapes. Then, to give an illusion of body, they would be colored

with fuchsine, which contains arsenic. Things hadn't really progressed much

from the days of Chaucer, whose Pardoner urged: Keep clear of wine, I tell you,

white or red, Especially Spanish wines which they provide And have on sale in

Fish Street and Cheap side. That wine mysteriously finds its way To mix itself

with others - shall we say Spontaneously? - that grow in neighbouring

regions.

Until the 1900s, when

a much stricter classification system came in for French wine and the

wine-making industry modernized its techniques, the story of wine swindling is

one more of continuity than change. It assumed many forms but the universal

trick was the attempt to pass bad wine off as good. In Bordeaux in the 1850s,

they might do this through chemical wizardry, distilling the bouquet of fine

claret from various artificial potions. In the fifteenth century, the chemicals

were more basic - one source mentions 'eggs, alum, gums and other horrible and

unwholesome things 'but the fundamental aim was the same: to touch up

undrinkable wine.

How was such

dishonesty policed? With endless, and endlessly evaded, punishments and

prohibitions. There have been laws against wine adulteration ever since

Charlemagne, who, in 802, issued what was probably the earliest edict in the

modern age against fraudulent wine.

Indeed it has been said that for there to be a wine fraud in the first

place, there must be a wine law.

Thus the fourteenth

and fifteenth centuries were particularly rich in wine laws, many of them local

to certain cities. In 1364, John Penrose, a vintner, was called before the

mayor of London and found guilty of selling bad wine. He was ordered “to drink a

draught” of his own bad wine and have the remainder poured over his head.

Also in 1364, the

town council of Colmar in Alsace made it an offence for an innkeeper to

adulterate wine by adding water, brandy, sulphur,

salt or any other ingredient. In fact there were countless attempts by

the authorities to stop vintners and innkeepers from mingling different kinds

of wine, and/or passing off plonk as fine wine. In 1419, a William Horold was

convicted of 'counterfeiting good and true Romney wine. He took old and feeble

Spanish wine and added “powder of bay” and other “unwholesome” powders.

In 1415 the town

innkeepers of Bordeaux were summoned to the town hall and told that if there

were any more cases of passing off other wines as those of Bordeaux, the

offenders would be put in the pillory and banished from the town.

Also in England, the

fourteenth century saw detailed legislation to protect wine drinkers from

fraud. On 8 November 1327, Edward III decreed that weak and out of condition

wine should not be mixed with any other. By the same ordinance every customer

had the right to see his wine being drawn from the cask, and it was forbidden

to put a curtain over the doorway leading down to the innkeeper's cellar. New

and old wine were not to be blended, or even stored in the same inn. Rhine

wines could not be sold by someone who sold the wines of Gascony, La Rochelle

and Spain.

Yet was Accum in 1820 still complaining about “factitious” wines of

“port” flavored with a tincture of raisins; of wine corks dyed red to look as

if they had been in long contact with the wine; of weak wines given “a rough

austere taste, a fine colour and a peculiar flavor”

with the use of astringents. One of the reasons that wine was especially prone

to adulteration was because, unlike ale, it was a luxury good, and an imported

one. Premium comestibles - tea in the nineteenth century spices always - are especially

tempting for fraudsters. Why therefore did wine not lose its reputation in the

centuries before the twentieth century, when it was such an unreliable drink?

Why, despite all the frauds to which it was subject, did it retain glamour and

even an image of wholesomeness?

Partly, this must

have been because not all wine was debased. In a good year, when the harvest

was full and ripe, the wine-makers of Burgundy or Chianti must have made some

fine bottles. Even if they did not understand the science of what they were

doing, hundreds of years of experience must have given wine-making families the

ability to make enjoyable and wholesome wines from good grapes. The problems

mainly arose, as we have seen, when the grapes themselves were not good, which

was when even respectable vintners resorted to chemical adjustments.

Sometimes, though,

wine's reputation was simply relative. During the eighteenth century, wine

could seem healthy because at least it wasn't gin, a drink for which there was

an unstoppable craze in the first half of the century. In 1726, there were

6,287 places in London where gin was sold, much of it rasping with turpentine

or sulphuric acid. If the adulteration of wine was

common, the adulteration of spirits was commoner. In the history of distilling,

adulteration is the rule, not the exception. The trade had always been rife

with diluters, “artificial Rectifiers” and “sophisticators”,

who would draw brandy from a turnip, or 'meliorate' spirits with green vitriol.

During the gin craze, the desire of the poor for penny drams of hooch drove

both licit and black market distillers to fabricate gin from whatever grain and

flavorings they could get. Wine was only sometimes poisonous. Even when pure,

gin was a kind of poison – “Mother's Ruiny” as the

anti-gin campaigners insisted - a drug which got into the milk of babies

through their drunken nurses, or which turned women to depravity and men to

disorder.

By the Gin Act of

1736 the British state even attempted - unsuccessfully - to ban gin. By

contrast with this juniper-sodden firewater, wine seemed a moderate drink. Sir

Hugh Platt, an Elizabethan courtier, beseeched his contemporaries to take an

“English and naturall drinke”

made from Royston grapes instead of poisoning themselves with imported wines.

“Native” fruit wines

were one of Accum's passions, too. Yet this could not

be the whole answer, because swindled wines were for sale too in France and

Italy where they were native. The truth is that until the process of

wine-making itself was more reliable, there would always be a large volume of

ropy wines; and ropy wines led inexorably to fraud. Legislation could try to

protect the consumer and the revenue from fraud, but the chances of success

were not good, until reliable wine-making was the norm. “The best test against

adulterated wine is a perfect acquaintance with that which is good,” wrote the

wine expert Cyrus Redding in 1833. He was thinking of British consumers, whose

palates were often so numbed by alcohol that they could not tell when their port

was 'cut' with spirits or when their claret was fake.

Merchants in Bordeaux

knew that when they were selling to the English market, they could get away

with mixing their wines with 10 per cent benicolo, a

cheap, alcoholic Spanish plonk, because English wine drinkers didn't know the

difference. Yet, increasingly, the French consumer was not much better off

Things had to get very bad in French wine production, in the nineteenth

century, before they could get better. There was an explosion of new substances

which became a part of wine making: sulphuric acid to

give wines a little sharpness, “allume” added to fix

the colour in falsely coloured

wines, salicylic acid to stop fermentation, iron sulphate to even out the

taste. Suddenly, it was hard to know on what basis to judge wine quality.

Previously, taste had seemed enough, but these new chemical substances

“rendered these traditional criteria obsolete.” Then, in the 1880s, phylloxera

hit, the tiny root-feeding aphid which wiped out almost 2.5 million hectares of

vineyard in France. Vines were also affected by mildew. Phylloxera, it has been

said, led to “a notable increase in dishonesty,” especially in the mid- 1880s.

The shortage of real grapes meant that vignerons were forced to desperate

measures. Vast amounts of raisins were imported from Greece to Marseilles to

fabricate raisin wines, labelled as the real thing. And 'wines' were even sold

which had no vine product in them at all, just chemicals, sugar and water.

Both wine-makers and

the French state recognized a desperate need to set new norms for wine-making,

to find new definitions of what 'wine' actually was. Special new laws were

passed dealing with adulteration. In 1889, raisin wines were specifically outlawed;

in 1891, the practice of 'chalking' was prohibited; in 1894 it was forbidden to

sell either watered-down wines or wines laced with extra alcohol. In the

meantime, Louis Pasteur had begun to establish the science which would finally

enable reliable avoidance of some of the most common failings in wine, without

recourse to swindling. In the 1860s, Pasteur identified many of the

microorganisms which caused different faults in the bottle. An excess

bitterness was due to degraded glycerol; flabbiness was caused by a

polysaccharide. In Pasteur's view, 'yeast makes wine, bacteria destroy it'.

This was the foundation of modern oenology. It would take several decades last

there was now the means available for scientific wine-making.

In 1905, the French

government issued a new law on wine quality, defining wine as the product of

'fresh grapes'. This was a start, It many fraudulent wines were still being

marketed, and there were numerous cases of generic wise being labeled, as if it

came from one of the prestigious wine regions such as Burgundy. Ultimately, it

was not prohibition by itself but enhanced standards of wine-making hich resolved the problem, The Appellation Con-rtolee system, which evolved in the 1920s with

Chateauneuf-du-Pape, but was officially established in 1935, laid out

extremely detailed rules for every stage of the wine-making process, drawing on

new expertise in oenology. Appellation Controlee is fundamentally a system of

geographical control, according to which 'Bordeaux', for example, must orne from the region of that name and nowhere else. But AC

also set rules about vine varieties, about pruning and training methods, bout

alcoholic strength, and about the quality of the grapes used.

The system was not

without teething troubles. Attempts to define which region was allowed to

produce which wine could lead to bitter disagreement, as in Champagne, where

there were riots over the question of whether the nearby Aube region was

allowed to produce true 'champagne' (in 1927 it was decided that it was). But

for all its rigidity and arbitrariness, most wine-makers found the new system

attractive, since it protected them from unwanted imitators and kept market

prices high. The system required higher level policing than that required by a

simple ban on adulteration - the French Service de la Repression des Fraudes still does spot checks to make sure that a Medoc

really is what it says, and not some clever imitation. For consumers, the AC

and AGC marks - which have now been extended to foods as well as wine - were,

and are, a guarantee of quality. They are based not just on the avoidance of

the bad, but on knowledge of the good - a knowledge that has extended from

producers to consumers.

By 2006, new research

was predicting that US wine consumption would overtake that of the French

within three years. Most of the wine being drunk is modest stuff, which may not

rank highly on a Parker scale, but there is, nevertheless, much greater consumer

awareness of how good wines should taste. Thanks to the efforts of Parker in

the States and Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson in the UK, and of films such as

Sideways, there is no need to be a 'wine buff' to know that Sauvignon Blanc

might taste of gooseberries or that Shiraz (or Syrah) has overtones of

chocolate. This knowledge might seem useless, but it is actually very powerful.

Jancis Robinson argues that “passing off has become increasingly difficult and,

just possibly, less rewarding as wine consumers become ever more sophisticated

and more concerned with inherent wine quality.”

In the 1950s, there

were cases of “fine” wine merchants buying a single vat of wine and passing it

off as Beaune or Beaujolais or Burgundy, depending on what the customer asked

for. It is much harder to imagine anyone getting away with this now.

It would be naive, to

suppose that wine adulteration is entirely a thing of the past. In fact, recent

reports show that wine

adulteration is currently on the rise.

But do such expensive

wines really taste all that much better than cheaper wines, for that we need to

start with the Paris Wine Tasting of 1976, known as the Judgment of Paris.

The tasting that revolutionized the wine world.

On 24 May

1976 the crème de la crème of the French wine establishment sat in

judgment for a blind tasting that pitted some of the finest wines in France

against unknown California bottles.

The only journalist

in attendance, George

M. Taber of Time magazine, later wrote in his article that "the

unthinkable happened," and in an allusion to Greek mythology called the

event "The Judgment of Paris," and thus it would forever be known.

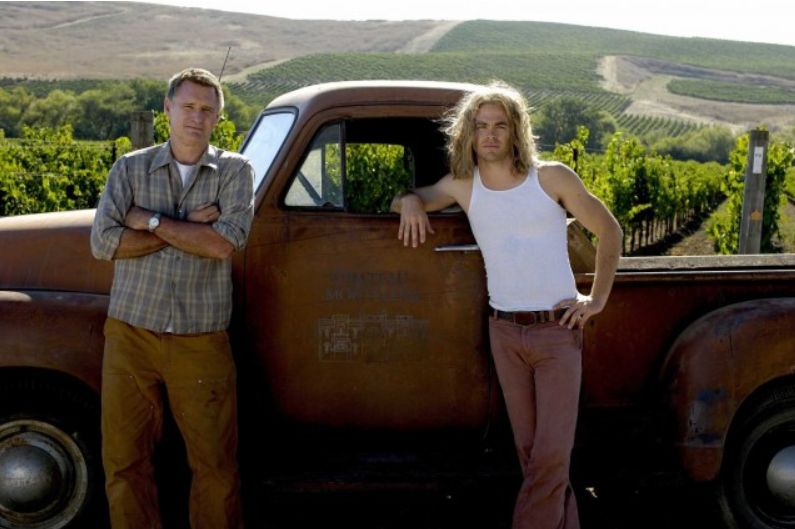

The American wines

were brought across with a group of 30 Californian winemakers:

At one point, Taber

says, a judge, Raymond Oliver, chef and owner of Le Grand Véfour,

one of Paris' great restaurants, sampled a white. "And then he smelled it,

then he tasted it and he held it up again, [and] he said, "Ah, back to

France!" Taber recalls.

Except it was a Napa

Valley chardonnay. The judge didn't know that. "But I knew," Taber

says. And once he realized what was happening, Taber says, "I thought,

hey, maybe I got a story here." Decades later, he penned The Judgment

of Paris, an account of that day and its aftermath.

When the scores were

tallied, the top honors went not to France's best vintners but to a California

white and red, the 1973 chardonnay from Chateau Montelena and the 1973 cabernet

sauvignon from Stag's Leap Wine Cellars.

Patricia Gallagher

(from left), who first proposed the tasting; wine merchant Steven Spurrier; and

influential French wine editor Odette Kahn. After the results were

announced, Kahn is said to have demanded her scorecard back. "She wanted

to make sure that the world didn't know what her scores were," says George

Taber.

As the founder of

this event, Steven Spurrier who only sold French wine believed that California

wines would not win, and would in turn boost his business. Critics of

this event suggested that wine tastings lacked scientific validity due to the

subjectivity of taste in human beings.

Spurrier backed this

up by saying, “The results of a blind tasting cannot be predicted and will not

even be reproduced the next day by the same panel tasting the same

wines.” It was even reported that a side-by-side chart of the best to

worst rankings of the 18 wines by a group of experienced tasters at this event

showed about as much consistency as a table of random numbers.

Jim Barrett described

the victory as: "Not

bad for kids from the sticks."

The tasting changed

history for wines of the New World, coming from outside of traditional wine

regions such as France, Italy and Spain.

In France, the

tasting raised more than a few eyebrows and some questions about the process

and the wine selection, with most of the Bordeaux producers claiming that their

wines were too young to be at their best.

Its significance,

however, stands unblemished.

Bottles of Chateau

Montelena and Stag's Leap Wine Cellars like those that won the contest are now

part of the collection at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American

History. And a 2008 film, "Bottle Shock," tells a heavily

fictionalized version of the story, with Alan Rickman as Steve Spurrier.

More recently Bo Barrett, who is married to Heidi Peterson

Barrett, maker of the

inaugural vintage of cult California wine Screaming Eagle, has taken on the

role of CEO.

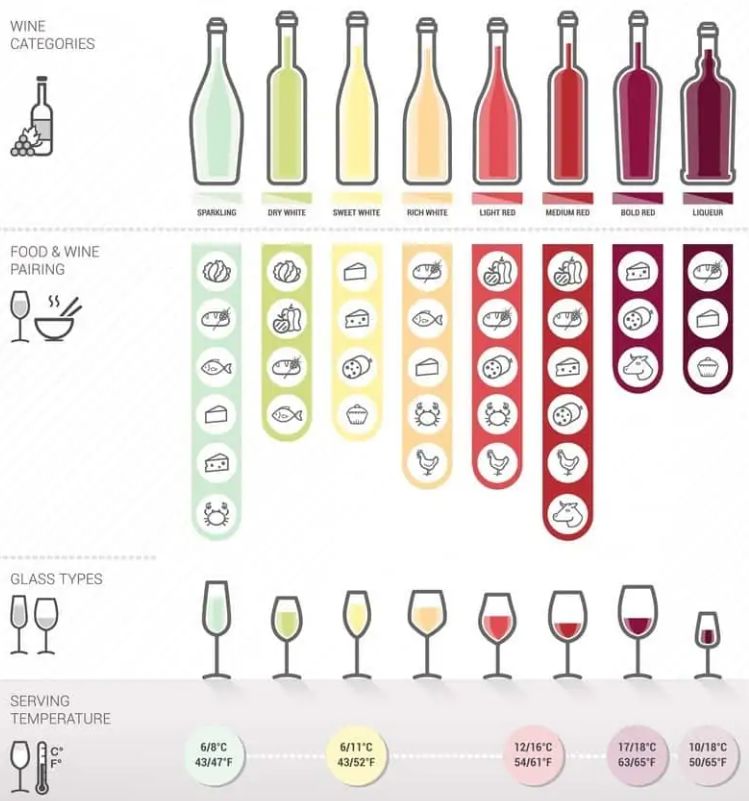

To prove that price

alone does not correlate to the taste of wine, a wine drinker only has to

sample his or her favorite wine served at two different temperatures.

Just a few degrees difference can make the wine from the same bottle of wine

taste vastly different. If you like your favorite wine served at slightly

below room temperature, but it is brought to your table ten degrees cooler, you

may think that you were given a different wine all together.

So how many other

factors or elements are out there, defining wine

experiences for

wine lovers? It turns out that there may be quite a few, such as label,

price, color, food pairing, and the most influential element, personal

experience. Several scientists, psychologists, and winemakers have been

proving the power of these influences for decades.

Compounding this

problem is our obsession with assigning numbers to things. In this day

and age, we like ratings and scores.

Think of when you

purchase an item on Amazon, one of the first things you do is look at the

number of stars your item receives. When you are on vacation, and you

want to find the best restaurant in the area, you look at Yelp or TripAdvisor

to see which restaurant received the highest rating.

This same concept of

rating the purchase of an item on Amazon, or the selection of a restaurant

based on the number of stars it receives on TripAdvisor, has spilled over into

the world of wine. There are different rating systems, but they all achieve

the same result, they make wine quality more identifiable and winnows down all

of the overwhelming noise.

For updates click homepage here