By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Understanding the 100 years of the current regime

in China Part One

While the Chinese

Communist Party (CCP) recently

acknowledged the Tiananmen Square debacle as an attempted revolution, we

will follow the example of Shaun Breslin in China Risen?: Studying Chinese

Global Power (March 2021), who pointed out how important it is what leaders

like Xi

Jinping and the CCP say about Chinese history all the while perpetuating

its own truths in addition we will analyze an extensive range of

Chinese-language debates and discussions, including explaining the roles of

different actors and interests.

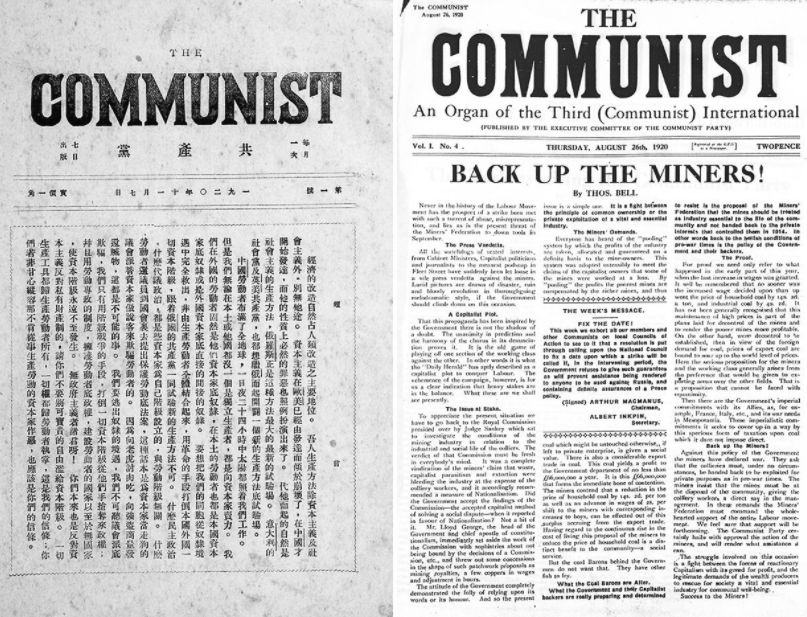

Early on already

Historian James Harrison considered the CCP party's actions of rewriting

Chinese history as "the most massive attempt at

ideological re-education in human history."1

In fact, even the

founding date of 1 July is

a myth and it seems clear from the available evidence that an organization

calling itself the Communist Party of China was born a full eight months before

the First National Congress as evidenced by the bulletin Gongchandang (left), published in November 1920 by

Chen Duxiu’s Shanghai group, and its British counterpart, The Communist,

dated August the same year:

As for First

National Congress, it has been detailed that representatives, disguised as

tourists, rented a small pleasure boat on which they officially formed the

party and approved their first political project on

3 Aug. 1921, not 1 July.

Political scientist

Peter Hays Gries stated: "It is certainly undeniable that in China the

past lives in the present to a degree unmatched in most other

countries. ... Chinese often, however seem to be slave to their

history".2 In fact just a few days ago Xi Jinping stresses

drawing strength from CPC history to forge ahead.

Buried at the end

of the most

important Chinese political speech in a decade, President Xi Jinping’s 66-page

address to the 19th party congress in November 2017, was one short line: “The

Chinese Dream is a dream about history, the present, and the future.” Tired

after 71 ovations over three-and-a-half hours, the audience may

have missed this sentence. Yet it illuminates how history underpins President

Xi’s “Chinese Dream” of national rejuvenation.

History plays an

increasingly important legitimizing role in China. As historian

Antonia Finnane writes:

Every country has its

national myths, most of which are grounded in or derived from history; but in

China, history alone is the bedrock. The People’s Republic doesn’t have a

religion, and it doesn’t have a constitution, or at least, not one that counts.

It no longer even has a revolutionary ideology. It just has history, lots of

it.

In contemporary

China, it’s put into practice with surgical skills. Specific memories of events

deemed sensitive by the state are not just forgotten, they are winnowed out and

selectively deleted. The Communist Party has succeeded in hacking the collective

memory.

National amnesia has

become what Chinese writer Yan Lianke calls a “state-sponsored

sport”. And as Beijing’s

global influence rises, its controlling instincts, to tame, to corral, to shape, to prune, to

expurgate history and historical memory, are increasingly being exported to the

world.

China has also

invoked history to legitimize its massive One Belt One

Road international

infrastructure scheme, despite critics claiming that its premise relies on mythologized

history.

But even in China,

not everybody believes what the State puts out, for example commenting on the

Chinese Academy of History; “They aren’t following an academic path,” said

a prominent history professor in Beijing, who said he declined the academy’s invitation

to collaborate on a project. “These people are doing this to suck up and win

promotion.”

A recent book

titled The Chinese Communist Party: A Century in Ten Lives Edited by

Timothy Cheek, Klaus Mühlhahn, and Hans van de

Ven “does not control history,” but it does know when and how to

seize historical opportunities. The first story in the book is how the

young Dutch revolutionary Henricus Sneevliet helped

establish the party. As an envoy of Moscow, the then uncontested center of the

global Communist movement, he also urged his Chinese comrades to form a united

front with Sun Yat-sen’s Nationalists...Or as has been known for a long time

while the PCCP/RC adopted a Soviet model of multinational state-building,

being ‘Chinese’ meant ‘socialist in

content while nationalist in form’.

To most observers,

China, that is the current the People's Republic of China (Chinese: 中华人民共和国;

pinyin: Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó; PRC) appears to be a uniquely bounded

and indivisible entity with a long and unbroken history, a single, unified

civilization. Asserting that it is slightly absurd to ask how China

became Chinese among others, including more recently Tim Marshall 3

Jared Diamond stated that "China

has been Chinese, almost from the beginnings of its recorded history."

Yet, the very

concepts of nation, race, nationality, and ethnic minority, especially in

China, are modern political constructs. For example, as we earlier pointed out,

during the dying days of the last Chinese dynasty, the

Qing (1644-1911), the Chinese state sought to colonize

various parts of its imperial frontier through Han resettlement. This

program of settler colonialism (not unlike the intentions of the

above-mentioned Nationalists) continued following the establishment of the

Chinese Republic and, as recently was pointed out in The Diplomat, intensified as state power grew in

the post-Mao era.

Communist scholars highlighted the significance of

the Yellow Emperor and Peking Man

The belief that history

brought it to power is one of the few ideological constants in the Chinese

Communist Party’s hundred-year saga.

Having grown up under

communist rule in 2007 already Chinese history scholar, Weishi

Yuan strongly criticized the

distorted story's told in China’s history textbooks and history education

while due to the publication of this article, his weekly supplement was closed

down by the government showing how concerned the CCP is about letting people

know about its own history.

Today, this type of

interference is much stronger, as exemplified by the fact that in February

2019, the Chinese government even issued specific rules covering the printing

within China of maps in books or magazines intended for sale in overseas

markets. Each map would require permission from provincial officials, and none

would be allowed to be distributed within the country. The possibility that a

Chinese citizen might see a map showing an unauthorized version of China’s

territorial claims was perceived as such a threat to national security that it

justified the involvement of the ‘National Work Group for Combating Pornography

and Illegal Publications,’ according to the regulations.4 To prove the point,

in March 2019, the authorities in the port city of Qingdao destroyed 29,000

English-language maps destined for export because they showed Taiwan as a

separate country.5

Government statements

explicitly connected the mapping laws and regulations of 2017 and 2019 to the

state’s ‘patriotic education’ education’ campaign. Part of their purpose was to

guide the teaching of schoolchildren in the correct view of the country. Messages

from the national leadership obsessively remind the population that the only

way to be a Chinese patriot is to fervently seek the ‘return’ of Taiwan to

control by the mainland; to insist that China is the rightful owner of every rock and reef in the South China

Sea (what other call the Pacific Ocean), and insist on maximalist claims in

the Himalayas. The official media constantly remind citizens of the state’s

territorial claims, exhort them to personally identify with those claims and

nurture feelings of hurt and shame towards unresolved border disputes. Paranoia

about national boundaries in China is not merely an obsession of online gamers

or Weibo patriots; it is central to the state itself. The speeches of Xi

Jinping made clear that his vision of national rejuvenation can only be

complete when all the territory claimed by China is under Beijing’s control.

Thus, China's

rewriting of history as a The Diplomat (written by the author of the forthcoming

“China’s New Empire” stated on 1 June the South China Sea disputes are today's

version of the early 20th century Balkans, where “some damned foolish thing”

can trigger a devastating global

conflict without precedence and beyond our wildest imagination.6

As recently pointed

out by Su-Yan Pan and Joe Tin Yau Lo the PRC state has adjusted its higher

education policies to realize renewed international prestige while at the same

time coping with external and internal challenges to its legitimacy due to

changing international and domestic circumstances. China's educational paradigm

mirrors the state’s power strategy in world politics. By serving the state's

diplomatic relations and national image building, Chinese universities have

increased their international profiles. Still, they have remained continuously

dependent on foreign-trained personnel for cutting-edge research and scientific

publications rather than cultivating innovation from indigenous knowledge and

domestically trained personnel. Moreover, China has reasons to celebrate its

‘brain gain’ successes - i.e., the ability to import highly educated

international human capital possessing the knowledge, skills, and/or potentials

on which China relies for economic growth, political stability, and global competitiveness.

While the CCP agrees

that on 23 July 1921, 50 delegates gathered in secret at an unprepossessing

house in the French

Concession in Shanghai and started arguing out the details of the new

party, after a week of this, on 30 July, the French police raided the house.

Only a dozen or so of the party members managed to escape. Less know and what

we will unravel here is the wider context of this development.

Hinted at by Weishi Yuan when he referred to China as a nation of

diverse ethnic groups, initially, Communist historians adopted a discursive

strategy closely resembling that of the Nationalist Guomindang intellectuals.

In their early

histories, Communist scholars highlighted the significance of the Yellow

Emperor and Peking Man in binding the heterogeneous peoples of the former Qing

empire into a single, organic minzu, which, following

Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek, they termed the Zhonghua minzu

(a key political term in modern Chinese nationalism related to the

concepts of nation-building, ethnicity, and race which as explained below was

borrowed from Japan). Yet, the heightened ideological struggle that accompanied

the collapse of the Second United Front and the publication of Chinas Destiny

forced CCP historians to adopt an alternative myth of national unfolding. In

particular, Communist intellectuals pointed to the recent discovery of a

racially distinct South Pacific hominid to counter the “fascist racism" of

the Guomindang and assert the multiracial origins of the Chinese people. At the

same time, faced (as were GMD scientists) with Japan's manipulation of ethnic

aspirations along the Qing frontier, CCP historians also manufactured intricate

ethno genealogies that placed the minorities at

the very origin of Chinese history. They linked the multivalent ‘‘Chinese” minzus together into a single organic, Han-centered whole.

In doing so, the Communists (like the Nationalists) projected Sun Yat-sen’s

desire for a future state of national unity backward in time using history,

ethnology, and archaeology to demonstrate the fundamental consanguinity and

antiquity of the Zhonghua minzu (Chinese: 中华民; Pinyin: Zhōnghuá

Mínzú) And as we have seen is still the rhetoric used by China today.

The Zhonghua minzu lie in the multi-ethnic Qing Empire, created in the

seventeenth century by the Manchus. The Manchus sought to portray themselves as

the legitimate rulers of each of the ethnic or religious identities within the

empire. And as Rebecca E. Karl explained, Chinese communism was part of

the reaction to the depredations of Western powers beginning with the

First Opium War in 1839, and the impetus for change had come from the

humiliation and exploitation suffered at the hands of foreigners. There were

many grievances against the emperor and the social structure, as had often been

the case in Chinese history, but what ultimately discredited these entities was

their failure to defend China and their obvious inadequacy compared to the

leading powers of the age.7

In the dying days of the

Qing dynasty, the Chinese state sought to colonize Xinjiang and other parts

of its imperial frontier through Han resettlement. This program of settler

colonialism continued following the establishment of the Chinese Republic and

intensified as state power grew in the post-Mao era.

Contrary

to Russia, where the Leninist revolution (also referred

to as a coup d'etat) was tied to its ability to

replace the economic order of the Tsarist regime with something more

egalitarian and more productive, whereby the Chinese Revolution, according

to Jeremy Friedman, had a decidedly "nationalist emphasis and

rhetoric."8

In stark contrast to

Western liberalism, Confucianism, and Chinese political culture more broadly,

hinges on individual rights and the acceptance of social hierarchy and the belief

that humans are perfectible.

Humans are not equally endowed; they vary in suzhi (素质) or quality. A poor

Uighur farmer in southern Xinjiang, for example, sits at the bottom of the evolutionary

ladder; an official from the ethnic Han majority is toward the top.

But individuals are

malleable, and if suzhi partly is innate,

it is also the product of one’s physical environment and upbringing. Just as

the wrong environment can be corrupting, the right one can be transformative.

Hence the importance of following the guidance of people deemed to possess higher suzhi, the people Confucius called “superior persons”

(君子) and the Communists now call “leading cadres” (领导干部).

So even a lowly

Uighur farmer can improve her sushi, through education, training, physical

fitness, or, perhaps, migration. And it is the moral responsibility of an

enlightened and benevolent government to actively help its subjects improve or,

as the China

scholar Delia Lin puts it,

to reshape “originally defective persons into fully developed, competent and

responsible citizens.” During its seven decades in power, the Chinese Communist

Party has repeatedly tried to remold recalcitrant students, political

opponents, prostitutes, and peasants alike.

Seen here preparing

for the 1 July 2021 100th anniversary of the current regime in China High

school students visit Xibaipo Memorial Hall (Xibaipo was an important base during China’s civil war)

From the Qing dynasty to present-day China

Following the

multiethnic Qing dynasty (1644-1911), its massive territory unraveled its

ethnic and provincial seams. Over the course of their long rule, the empire’s

Manchu rulers had fashioned a loose nomadic-style confederation of five ethnic

constituencies (today codified as the Manchu, Han, Mongol, Tibetan, and Hui

nationalities), doubling the size of the previous Ming dynasty’s territory and

boosting its population to 420 million from 130 million. Yet, this phenomenal

growth was not balanced. The empire's population ballooned at the geographic

and political center among its sedentary, densely populated Sinic

communities (today reimagined as a homogeneous Han nationality). At the same

time, its territorial advances occurred along the empire’s rugged nomadic and

seminomadic periphery. It should come as no surprise that once this rather

bloated and deformed “geo-body’’ started to decay in the nineteenth century, it

was set upon by predators from both within and without. By late 1911, the core

provinces of Ming China had broken away from the Qing court while many of its

impoverished peasants sought out new land and opportunities in the remote and

formerly sequestered frontier regions. At the same time, the dependencies of

Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang sought their political independence from

“China" while England, Russia, Japan, and other imperialist powers carved

deeper zones of influence on the rotting Qing geobody.

Attempting to stem this tide of disunity, Chinese revolutionaries

quickly announced a new Republic of China (1912-1949). They declared their

intention to assert sovereignty over all the former subjects and territories of

the Qing empire, which was reconstituted as a free and equal “republic of five

races” (wuzu gonghe 五族共和).

What came next is

important to understand the true history of the CCP and how the

current People's Republic of China (Chinese: 中华人民共和国; pinyin:

Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó; PRC) and while we have pointed to the two forms

of Nationalism of which the CCP/PRC is one we have to introduce a third

influence.

As we have

seen, 1919 was a year of radical cultural

transformation in China. Just how radical it was, as illustrated by the

U-turn taken in the career of Hu Shi (1891-1962). He had been a professor at

Beijing University since 1917. Today he is famous as one of the authors of the

magazine New Youth (新青年;

pinyin: Xīn Qīngnián) and as an early advocate of baihua (the “Plain Language” simplified Chinese: 白话文;

traditional Chinese: 白話文;

pinyin: báihuàwén), a vernacular based on the Beijing

dialect and infused with Western loanwords.

With disappointment

rife about the political mess left in the wake of the 1911 Revolution, many

intellectuals turned their attention to what they deemed the deeper substratum

of Chinese social life: its culture. Critique moved from considerations of politics

as state form, now a sphere condemned as endlessly corrupt and ineffectual, to

an unsparing critique of the culture that underpinned the structures of

everyday social hierarchy. The major target of this critique from the New

Culture through the May Fourth period (1915-1925) was Confucianism, which was

imputed as the mode of the social reproduction of hierarchy in elevated and

everyday behavior alike. The feudal infestation had to be overcome.

From the mid-1910s

into the 1920s, the claims made for culture were totalistic. Everything was

said to have a cultural root. That cultural root was not gently sinological nor quaintly traditional or harmoniously

uniting, but rather entirely rotten, toxic even. Cultural rot became an

explanation for all manner of vice and ill and social problem, from the

high-level corruption of officials through to the everyday gendered practices

that sacrificed women's individuality and men’s freedom to family honor on the

altar of marriage. Indeed, the proliferation of what was identified as “social

problems" went hand in hand with what were understood to be the

devolutionary properties of Chinese culture, where the insufficiencies of the

latter were now said to subtend all failures of Chinas modern historical

passage. This radical critique and condemnation of culture and China not only

characterized but animated the New Culture/May Fourth movement, an extended

period of existential crisis in “Chinese-ness” that constituted the first of

several cultural revolutions in China's twentieth century.

An alternative

paradigm of the New Culture/May Fourth purveyed until very recently in PRC/CCP

scholarship, holds that this period led teleologically to the introduction of

Marxism and the formation of the Communist Party (1921), which is the true

revolutionary successor to this (petty) bourgeois phase of cultural critique.

Highlighting the role of the Communist Party in organizing and leading

progressive historical initiatives, this PRC narrative turns the New

Culture/May Fourth into a mere transmission belt for Marxism; it thus

forecloses the more radical aspects of the culture critique (its anarchistic

tendencies, for example), consigns to historical oblivion the competing liberal

contribution and emphasizes to the exclusion of much else the coming-into-being

of the Bolshevik-Communist nexus of political-cultural social relations and

knowledge production. In this party-centered narrative, the Russian Revolution

of October 1917 propels history into motion in a linear unbroken line traced

from Russia to China to the founding of the Chinese Communist Party.'9

In reality, many

different people were involved in making the New Culture Movement since many

groups participated in the patterning of reality, leading to the network of

reference points later inscribed into the buzzword. The academics debated. The

newspapers invented conspiracy theories. The politicians made their deals with

foreign powers about Shandong in reference to

the Paris Peace Conference. But in a way, no one really made the New

Culture Movement since no one group was responsible for combining these

patterns into the New Culture Movement’s matrix of reference points.

Although the Movement

was highly influential, many of the intellectuals at the time opposed the

anti-traditional message, and many political figures ignored it. "this

limited May Fourth individualist enlightenment did not lead the individual

against the collective of the nation-state, as full-scale, modern Western

individualism would potentially do."10 Chiang Kai-shek, as a nationalist

and Confucianist, was against the iconoclasm of the May Fourth Movement. As an

anti-imperialist, he was skeptical of Western ideas and literature. He

criticized these May Fourth intellectuals for corrupting the morals of youth.11

When the Nationalist party came to power under Chiang's rule, it carried out

the opposite agenda. The New Life Movement promoted Confucianism, and the

Kuomintang purged China's education system of western ideas, introducing

Confucianism into the curriculum. Textbooks, exams, degrees, and educational

instructors were all controlled by the state, as were all universities.12 Some

conservative philosophers and intellectuals opposed any change, but many more

accepted or welcomed the challenge from the West but wanted to base new systems

on Chinese values, not imported ones.

Confucianism from old to a new third way

Also called

the New Confucianism (Chinese: 新儒家; pinyin: xīn rú jiā) is an intellectual movement

of Confucianism that began in the early 20th century in Republican China, and

as we shall see further developed in post-Mao era contemporary China. It is

deeply influenced by, but not identical with, the neo-Confucianism of the Song

and Ming dynasties.

A native of

Guangdong, Kang Youwei, as was the case of many of

his generation, was sent by his family to study the Confucian classics in order

to pass the Imperial examination at an early age. In 1879 and 1882, Kang

visited Hong Kong and Shanghai. Deeply impressed by the sheer modernity of the

two cities under foreign administration, he bought numerous Western works in

Shanghai to study. In 1891, he opened a school in Guangzhou to teach Western

learnings and offer his own interpretations of Confucianism, declaring that

the Old Texts (Chinese: 古文經;

pinyin: Gǔwén Jīng) was fabricated by Liu Xin

also known as Liu Xiu (Chinese: 劉秀) and resulted in the sclerosis of Chinese

intellectual tradition, Kang drew on foreign political systems to inform his

reformist ideas that he rationalized in the framework of the New Text. Adopted

by Confucians such as Dong Zhongshu, this school

advocated a holistic interpretation of Confucian classics and viewed Confucius

as a charismatic, visionary prophet.

Initially, the reformers of Chinese Nationalism during the

anti-Manchu 19th century proposed a constitutional monarchy that would

include the Manchu emperor: their notion of a "yellow race" was

broad enough to include all the people living in the Middle Kingdom. In the

wake of the abortive Hundred Days Reform of 1898, which ended when the empress

dowager rescinded all the reform decrees and executed several reformer

officials, several radical intellectuals started advocating the overthrow of

the Manchu dynasty. Not without resonance to the 1789 and 1848 political revolutions

in Europe, the anti-Manchu revolutionaries represented the ruling élites as an

inferior "race" which was responsible for the disastrous policies

which had led to the decline of the country, while most inhabitants of China

were perceived to be part of a homogeneous Han race. In search of national

unity, the very notion of a Han race emerged in a relational context of

opposition to foreign powers and the ruling Manchus. For the revolutionaries,

the notion of a "yellow race" was not entirely adequate as it

included the much-reviled Manchus. Whereas the reformers perceived race (zhongzu) as a biological extension of the lineage (zu), encompassing all people dwelling on the soil of the

Yellow Emperor, the revolutionaries excluded the Mongols, Manchus, Tibetans,

and other population groups from their definition of race, which was narrowed

down to the Han, who were referred to as a minzu.

Lydia Liu has

remarked that the word minzu was invented in Japan, minzoku entered the Japanese vocabulary only in 1873.

However, the word did not find more popular usage in China before Chinese

students and intellectuals, who were sojourning in Japan, introduced the word

with its modern meaning to the Chinese public around 1898. This was when

cultural nationalism and the notion of "national essence" were

booming in Japan.13

Pictured below in

1906, the library of the Society for the Preservation of National Learnings,

the first private library in China, opened its door in Shanghai.

Its founder welcomed

the fact that more and more foreigners were interested in ancient Chinese

objects and books. It showed that Chinese civilization had an important role to

play in the progress of humanity. However, he was deeply concerned by the hemorrhaging

of Chinese antiquities and books to overseas collectors, museums, and

researchers. Thus, the library assumed the mission of preserving Chinese

material civilization in China and had a collection of 60,000 ancient books,

most of which were donated. The library issued a statement declaring: "To

promote nationalism, the preservation of ancient learnings and the promotion of

national radiation now bears upon the shoulders of everyone." The library

later changed hand to the "Rare Book Preservation Society"

during the Japanese occupation.

Thus during the first

half of the twentieth century, cultural and political revolutions link together

to form a historical telos that favors the CCP's revolutionary ideology. Under

this paradigm, revolution dominated public life in modern China and constituted

the overarching themes of modern Chinese history. Specifically, these themes

are the Revolution of 1911 that overthrew the imperial system and established a

Chinese nation-state; the May Fourth and New Culture Movements of the mid-1910s

to 1920s that replaced 'feudal' Chinese traditional culture with Western

democratic and scientific enlightenment; and the Communist Revolution from 1949

onwards that 'compensated' for the Nationalist KMT's abortive

revolutions to bring about China's long-awaited national revival by the drastic

steering of Chinese society, its economy, and politics in a socialist

direction.

By contrast, the

second dominant historiographical theme takes modernization as the dominant

trend that permeated modern China. Since the middle of the nineteenth century,

China's socio-political structure and technological backwardness rendered the

country extremely vulnerable to colonial and imperialist profiteering advances.

Inequitable treaties were imposed on the Qing government, which opened up the

path for major Western powers and the Empire of Japan to penetrate China’s

economy and wrestle for special privileges. The modernization paradigm

emphasizes China's process of reconstruction, which began with the

Self-Strengthening Movement (1861-1895), the Hundred Days' Reform (1891), and

the New Policies (Xinzheng, 1901-1911). The Manchu

dynasty launched these to facilitate Western technology, industry, armaments,

and institutional models. Underscoring China's path to social and political

modernization, this historiographical perspective portrays revolutions as counterproductive

and damaging to China's interests.

Despite the

contrasting visions of the two historiographies concerning revolution, both

paradigms are wedded to the concept of linear progress, creating a dichotomy

between tradition and modernity.

Recent years have

witnessed the rise of a historiographical trend that challenges this

progressive narrative. Elisabeth Forster's monograph on the New Culture

Movement proposes the story of the New Culturalists as being astute

entrepreneurs and self-promoters, who took over the intellectual landscape

around 1919, and not entirely due to their intellectual merit.14

At a cultural level,

many revolutionary intellectuals accused Confucianism of being the spiritual

culprit responsible for China's backwardness and an accomplice in the

dictatorship of the absolute monarchy. Refuting Kang's advocation of adopting

the Confucian calendar, Liu Shipei (1884 –1919)

argued to calculate years according to the Yellow Emperor. Having referred to

him before, Shipei was

a philologist, Chinese anarchist, and revolutionary activist. While he and his

wife, He Zhen, were in exile in Japan, he became a fervent nationalist. He then

saw the doctrines of anarchism as offering a path to social revolution while

remaining intent on preserving China's cultural essence, especially Taoism and

the records of China's pre-imperial history. In 1909 he unexpectedly returned

to China to work for the Manchu government.

Re-invoked by the present-day

Communist Party of China (CPC), annual ceremonies are held to worship the

imaginative Yellow Emperor.

The Yellow Emperor was a native of Mesopotamia…..

The influence of this

Japanese culturalist nationalism among late Qing Chinese intellectuals cannot

be emphasized too much. Chinese students and intellectuals began to seek exile

or study in Japan during the last few years of the 1890s. This was a period in

which the homogenization of the cultural nation and the political nation

prevailed in Japan and penetrated the Chinese political vocabulary. It was

exactly this idea of the nation as a culturally and politically unified entity

picked up by Chinese intellectuals in Japan after 1898. Liu Shipei

(1884-1919) wrote in 1903 that "minzu is the

unique character of guomin." This culturalist

nationalism carried two political imperatives in the 1900s. Chinese culturalist

nationalism first emerged as both a doctrine of popular sovereignty and a

movement for a Chinese nation-state independent from external oppressors. It

follows that the people who formed the Chinese nation-state should be

ethnically and culturally identical. Culturalist nationalism also implied that

political reforms should be undertaken to preserve selectively updated

traditional culture. China could only hope to have a unified and integrated

modern nation-state if she borrowed wisely from different political elements

within Western civilization.

But the essential

point remains that culturalist nationalism reveals a complex exchange between

opposing ideas. Conservative reformers and radical revolutionaries thought of

culturalist nationalism in the same way. Monarchist reformers in China and

Japan expressed a conservative culturalist nationalism to legitimize the Qing

dynasty. They argued that the Manchu had been assimilated into the Chinese

nation and began reinterpreting traditional sources to legitimize a

constitutional monarchy. In 1898, Liang Qichao, who escaped the Empress Dowager

Cixi's purge but continued to press for reform from Japan, even communicated in

classical Chinese with Shiga Shigetaka, advisor to

the Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time. This was hoping to obtain help

from the Japanese government to restore the Guangxu Emperor to power. In

contrast, revolutionary intellectuals linked with Sun Yat-sen's (1866-1925) Tongmenghui (Revolutionary Alliance), such as those of the

National Essence School and the Southern Society, associated national essence

with Chinese history. This meant that China's ancient socio-political system

and cultural traditions would be seen to comply with radical political reforms

inspired by modern Western politics and to rationalize revolution. As Zhang Taiyan remarked, national essence served to "incite

ethnic nationalism, promote patriotism and fabricate a history of the

Han."

Revolutionary

culturalist nationalism was forged to fit a republican political construct. To

this end, they even borrowed from the French orientalist Albert Etienne

Jean-Baptiste Terrien de Lacouperie's (1844-1894)

theory that the Yellow Emperor was a native of Mesopotamia.

Lacouperie’s argument was warmly accepted by Chinese nationalists

such as Deng Shi (1877-1945), Huang Jie (1873-1935), LiuShipei

(1884-1919), and Zhang Taiyan (1869-1935), who

promoted Sino-Babylonianism to support an anti-Manchu

revolution. They argued that because the Han Chinese were originally migrants

from Mesopotamia, they should have the physical strength and the mental

toughness to start a revolution against their oppressors. As descendants of the

Yellow Emperor, the first Chinese king of the migrants from Mesopotamia, they

must have faith in creating their own country.15

In addition to

showing a racial genealogy from the Yellow Emperor to contemporary Han Chinese,

Sino-Babylonianism revealed the complex networks of

human migration that began in prehistoric times and continued to the present.

For Xiong, the migration of the Bak tribe to China was merely an example of the

constant flow of people across Eurasia. More importantly, migrants were often

stronger and more determined to succeed in difficult conditions.16 Not only

did they have to adapt and adjust to the new environment. Still, they also had

to compete with the locals to control land and resources.

Thus, for Xiong, the

migration of the Bak tribe to China was an episode of global significance.

First, it demonstrated that since prehistoric times there had been a constant

movement of people from continent to continent, forming multiethnic

communities in various parts of the world. Because of the high volume of

migration, racial mixing amid racial competition had been the driving force of

history. Second, for contemporary Chinese, the migration of the Bak tribe

underscored the importance of coming to terms with the age of imperialism and

colonialism. As Europeans migrated to East Asia in droves through imperialist

expansion and colonial rule, they would soon be the new rulers of East Asia if

the natives could not match their competitiveness and military prowess.

The same global scope

is also found in Bai Yueheng's article “Liding xingzheng qu beikao” (Notes on Dividing the

Administrative Districts, 1912). Bai suggested constant attempts had been made

to match political boundaries with natural boundaries throughout human history.

When a political boundary follows “the division in the mountains and the unity

in rivers” (shanli shuihe),

he said, it renders what is invisible visible, making the natural boundary

clear and concrete. When a political boundary allows effective use of natural

resources, he asserted, it creates “peace to the country and prosperity to the

people” (guotai minan.)17

In China, Bai argued,

throughout history, political leaders had made many attempts to match human geography with natural geography.

But Bai considered

that the success of the 1911 Revolution provided an important opportunity for

rethinking and remaking the political divisions in China.18 Unlike previous

attempts, he argued, the goal of restructuring the administrative districts

after 1911 was not to give the central government more control over the local

areas or expand the bureaucracy to remote places. Rather, the political

reorganization was to reflect the characteristics of natural geography and to

facilitate the movement of people and goods. The new political division, Bai

suggested, should 'model after nature,' focusing on expanding existing networks

that connected the local market to regional and global markets. Its goal was to

serve China and the world, making the country more connected to the global

system of circulation, consumption, and production.19

Thus the surge in nationalist

activism and the intensified insistence on establishing and preserving

sovereignty around that time reflected key transformations and continuities. It

marked a shift in conceptions of organizing world societies from a hierarchy of

time, which was based upon the idea of progression from barbarism to

civilization, from a hierarchy of time to the

hierarchy of space that emphasized the right of self-determination and

the defense of a conjoined territorial and political integrity. This

transition in worldview led to nation-states' production that greatly resembled

the sovereign units of the prior tributary order. That is, a modern China

filled most of the space of the old Qing Empire.

Continued in Part Two.

1. James P.

Harrison. The Long March to Power: A Political History of the Chinese Commimist Party, 1921-1972 (London: Praeger, 1972).

2. Peter

Hays China's New Nationalism: Pride, Politics, and Diplomacy, 2005, 15.

3. Tim Marshall,

Prisoners of Geography, 2015.

4. Zhang Han, ‘China

Strengthens Map Printing Rules, Forbidding Publications Printed For Overseas

Clients From Being Circulated in the Country’, Global Times, 17 February 2019.

5. Laurie Chen,

‘Chinese City Shreds 29,000 Maps Showing Taiwan as a Country’, South China

Morning Post, 25 March

2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3003121/about-29000-problematic-world-maps-showing-taiwan-country.

6. See our analyses

of can a potential future Pacific War be avoided? as exemplified

in: http://www.world-news-research.com/PacificRising6.html.

7. Rebecca E. Karl,

Staging the World: Chinese Nationalism at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,

2002, p.195.

8. For this, see

Jeremy Friedman, Shadow Cold War: The Sino-Soviet Competition

for the Third World, 2015.

9. Rebecca E.

Karl, China's Revolutions in the Modern World: A Brief Interpretive History,

2020

10. Chen, Xiaoming

(June 5, 2008). From the May Fourth Movement to Communist Revolution. SUNY

Press. p.8.

11. Joseph T. Chen

(1971). The May fourth movement in Shanghai: the making of a social movement in

modern China. Brill Archive. p.13.

12. Werner Draguhn, David S. G. Goodman (2002). China's communist

revolutions: fifty years of the People's Republic of China. Psychology Press.

p.39.

13. Lydia H. Liu, The

Clash of Empires: The Invention of China in Modern World Making, 2006.

14. Elisabeth

Forster, 1919 –The Year That Changed China: A New History of the New Culture

Movement, 2018.

15. Kai-wing Chow,

"Imagining Boundaries of Blood: Zhang Binglin

and the Invention of the Han 'Race’ in Modern China,” in The Construction of

Racial Identities in China and Japan. Edited by Frank Dikotter

(Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 1997), 34-52; Frank Dikotter, The Discourse of Race in Modern China (Stanford,

CA: Stanford University Press, 1992), 116-23; John Fitzgerald, Awakening China

Politics, Culture, and Class in the Nationalist Revolution (Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press, 1996), 67-88; Shen Songqiao,

“Wo yi wo xue jian xuan yuan: Huangdi shenhua yu wanqing

de guozu piango,” Taiwan shehui yanjiujikan 28.2 (1997):

1-77; Tze-ki Hon, "From a Hierarchy in Time to a Hierarchy in Space:

Meanings of Sino-Babylonianism in Early 20th Century

China/’ Modern China 36.2 (2010): 139-69.

16. Xiong Bingsui, “Zhongguo zhongzu kao ” Dixue

zazhi 18 (1911): 3b.

17. Bai Yueheng, ‘lading xingzheng qu beikao," Dixue zazhi 7-8 (1912): 1a.

18. Ibid., 1b.

19. Ibid., 1b.

For updates click homepage here