By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Understanding the 100th year of the current

regime in China Part Two

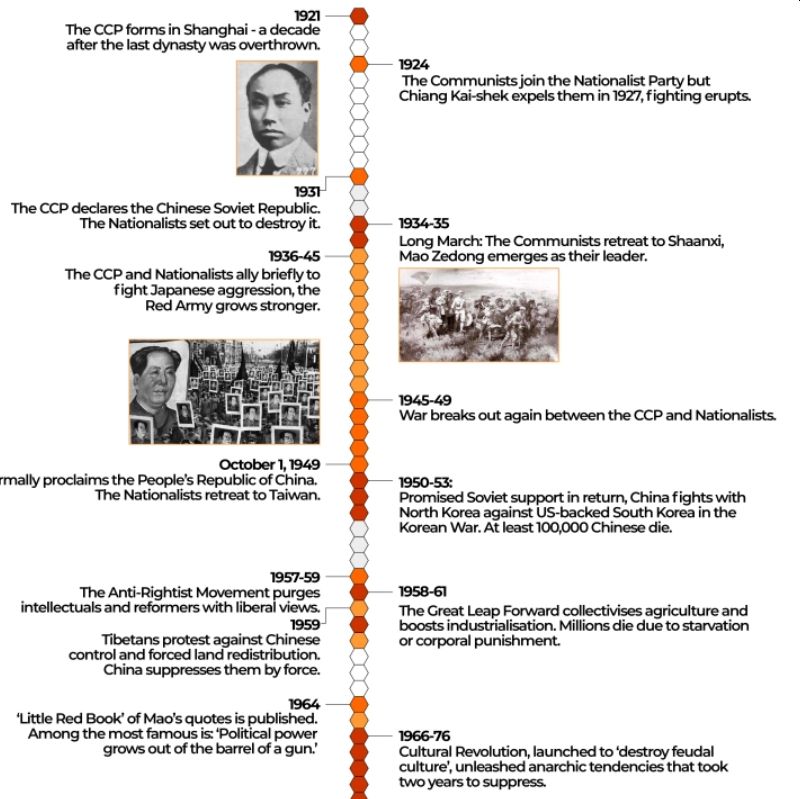

We started this

multi-part investigation about the CCP/PRC, with the premise that Chinas cultural

past is crucial for understanding its national presence. Where we pointed out

that early on already Historian James Harrison considered the CCP party's

actions of rewriting Chinese history as "the most massive

attempt at ideological re-education in human

history." For example, left out from CCP/PRC history books

is that most communists entered politics through nationalism whereby leading

nationalists in turn (including Sun Yat-sen and his successor Chiang Kai-shek)

similarly adopted Leninist precepts thus creating a right-left overlap

something the CCP/PRC tries to ignore and erase. And also that at the CCP’s

birth in 1921, communism was the least promising of many contending political

forces in a country devastated by floods, famines, warlordism, and corruption. The

12 men who founded the party were fascinated by the new, poorly understood

ideology of Marxism, which contended for influence with liberalism, social

democracy, anarchism, fascism, and other isms that claimed to show how to

restore China’s greatness.

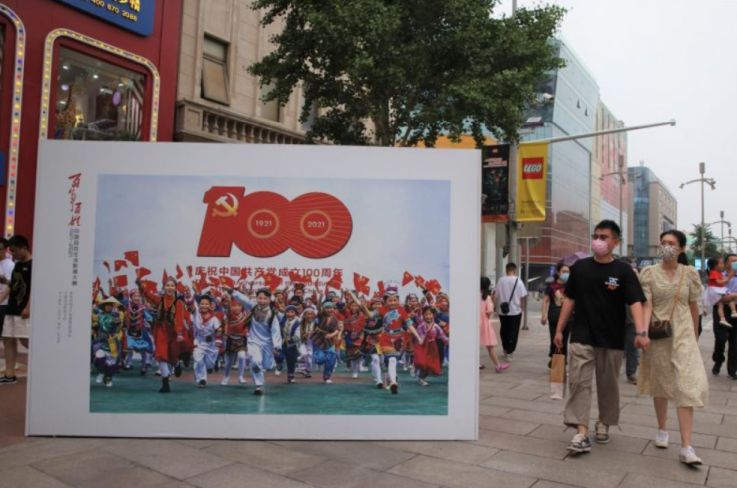

On 1 July 2021, the

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will celebrate

its centenary anniversary. Over the past several months, the country has

been inundated with a 24/7 tsunami of propaganda. Bookstores are filled with

newly minted books with the ubiquitous hammer-and-sickle on their covers.

China’s consumer goods industry is churning out a surfeit of communist kitsch,

busts, buttons, statues, posters, plates, paintings, commemorative coins, and

other memorabilia. Commemorative films play on television and in movie

theaters. Work units and school children are being organized to go on pilgrimages

to revolutionary sites (so-called “red tourism”).

Thus as seen

above some efforts fall into the formats one might expect before an important

date. But these traditional exercises have been supplemented with new

elements that seem aimed at saturating the public consciousness and people’s

conversations while reinforcing Xi’s position as the country’s paramount

leader. A massive public education campaign focused on CCP history was launched in February. It included the

release of 80 national

propaganda slogans,

including several with Xi at the center, a scale that the China Media Project

described as “unprecedented in the reform era.”

As the CCP readies

the 100th birthday cake, it is worth reflecting that, among

commentators of a certain age, both inside and outside China, few expected this

moment to come. In 1991, it was widely assumed that the collapse of Soviet

communism heralded the demise of what had started as its Chinese franchise (the Comintern

in Moscow was heavily

involved in the CCP’s establishment.) And yet, here we are. Either all

modernizing roads do not, as was once thought, lead to liberal democracy, or

China is taking the mother of all detours.

And as recently

mentioned in the South China Morning Post: “Don’t

believe a word that Xi Jinping tells you about China’s history. Let’s think

properly about what that history was across the 20th century. And

that’s difficult to do because over the last five, six, seven years, the

archives have shut down in China.”

The Chinese Academy

of Social Sciences has established a specialist history unit to propagate the

official version of the past. And this year Beijing set up a hotline for

citizens to report

historical nihilism to

authorities.

The latest edition of

the CCP’s official concise history condenses the decade-long turmoil of the

Cultural Revolution into three pages.

The party’s official records

show that it opened its first congress in Shanghai on July 23, 1921. But the

anniversary of foundation was set on July 1 because, according to a record, Mao

merely remembered that the first party congress had been convened “in July”

when the CPC decided on the date of the anniversary in the 1930s. Plus, by now

several of the attendees have been airbrushed out of official accounts,

some of them accused of collaborating with the Imperial Army in the treacherous

civil war and Japanese occupation in the 1930s.

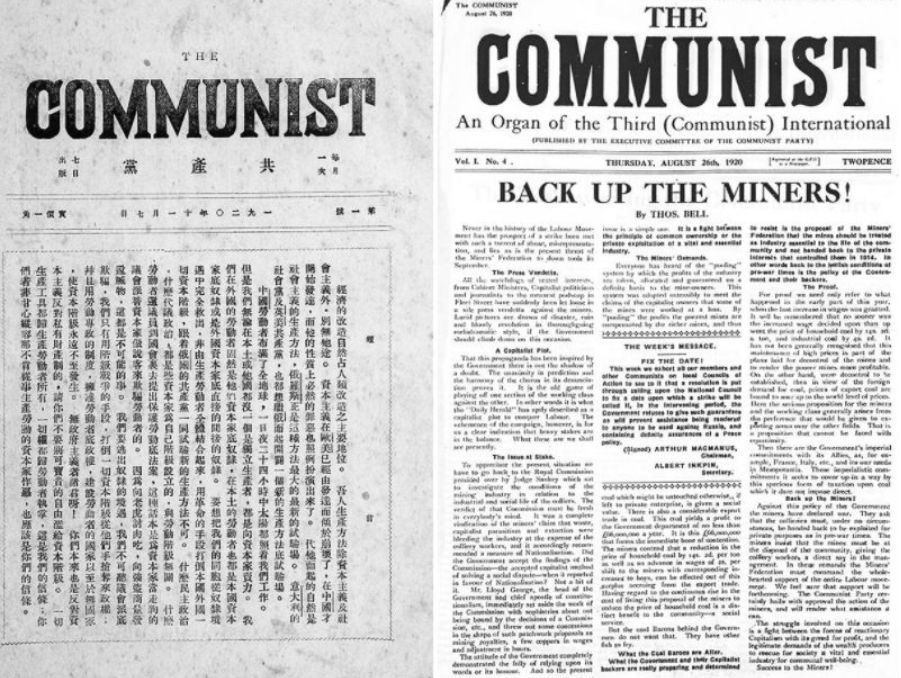

It seems clear from

the available evidence that an organization calling itself the Communist Party

of China was born a full eight months before the First National Congress as

evidenced by the bulletin Gongchandang (left),

published in November 1920 by Chen Duxiu’s Shanghai group:

In fact, history

weighs heavily on Xi, who keeps mentioning the Soviet collapse. He is waging a

campaign against what he calls “historical nihilism”, that is, any grumbling

about communism’s past. One Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, is held up as the

archetypal nihilist for denouncing Stalin’s brutality in 1956. That event

haunts Xi. Party literature says it led to the Soviet Union’s demise. Much of

Xi’s energy is focused on making sure the party learns the Soviet lesson. Mao

must remain a saint.

As the Economist

reported yesterday: The most dangerous threat to Mr. Xi comes not from the

masses, but from within the party itself. Despite all his efforts, it suffers

from factionalism, disloyalty, and ideological lassitude. Rivals accused of plotting

to seize power have been jailed. Chinese politics is more opaque than it has

been for decades, but Mr. Xi’s endless purges suggest

that he sees yet more hidden enemies.

And in the

July/August 2021 issue of Foreign Affairs Jude Blanchette Freeman Chair in

China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies

writes: The CCP’s long experience of defections, attempted coups, and

subversion by outside actors predisposes it to acute paranoia, something that

reached a fever pitch in the Mao era. Xi risks institutionalizing this paranoid

style.

But to ensure that

history really appears to be on its side, the party spends an inordinate amount

of time rewriting it and preventing others from wielding their pens. Few

Chinese leaders have done so with as much verve as Xi, who launched his reign

in 2012 by making a major speech at an exhibition on Chinese history. Since

then, he has waged war on “historical nihilism,” in other words, those who want

to criticize the party’s missteps. Xi has many goals, such as battling

corruption, fostering innovation, and projecting power abroad through his Belt

and Road Initiative, but controlling history underlies them all.

This belief in the

power of history is one of the few constants in the CCP’s hundred-year saga.

Though based on one creed, its ideology has actually been a blunderbuss of

strategies: it started as a group of orthodox Marxists who looked to the

industrial proletariat to lead the revolution, lurched to a rural-based party

that tried to foment a peasant rebellion, morphed into a the ruling party

dominated by a personality cult built around Mao Zedong, transformed itself

into an authoritarian technocracy, and now presents itself as in charge of a

budding superpower dominated by a strong, charismatic leader.

Three interlocking

ideas unite these stages. Many Chinese patriots have held one since the

nineteenth century: modernizing China means making it wealthy and powerful

rather than free and democratic.1 Another, also shared by Chinese patriots, is

that only a strong state can achieve this. And finally, that history anointed

the Communist Party to achieve these utilitarian goals.

A teacher and her

students in Lianyungang, China, pose with Communist Party emblems during a

class about the party’s history in June 2020:

As we have initially seen, China’s major aim in World War I

was the return of Qingdao and the surrounding Shandong Peninsula. Germany had

occupied the Chinese port city of Qingdao in 1897, negotiating a forced lease on the city and its surroundings that, like the British

lease on Hong Kong’s New Territories, was due to run through 1997. But in 1911

and 1912, the Qing dynasty, which had signed those treaties, was overthrown.

The new government in Beijing, known as the Beiyang

government after the army corps that formed it, negotiated with foreign powers

to restore China’s territorial integrity. It sought the restitution of lands

given up by the Qing dynasty in the unequal treaties of the 19th century, starting with

Qingdao and the Shandong Peninsula.

The problem for China

was not that Germany refused to cooperate. It was that Germany’s territory in

the Shandong Peninsula had already been taken, by Japan. At the beginning of

World War I, the United Kingdom, desperate for Japanese naval support in the Pacific,

had offered the country the German naval base at Qingdao in exchange for

entering the war on the Allied side. Japanese forces took Qingdao in November

1914.

When news reached

China on 2 May 1919 of accepting the Japanese claims, it shocked the nation.

The hopes of those who had marched to welcome victory in November were dashed.

Such was the uproar that the Chinese delegation did not sign the Versailles

Treaty on 28 June.

The 3,000-strong

demonstration involved students from a dozen institutions in the capital and

ended with a small riot. They marched to the Legation Quarter intending to

present letters of protest to the Allied ministers, but it was a Sunday – and a

beautiful spring one, so the diplomats were largely out of town in the Western

Hills. After some hours of confrontation with police, the students marched to

the home of Cao Rulin, then Minister of

Communications, but formerly Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs, and deeply

involved in the 1915 negotiations with Japan and the secret loans of 1918.

Some of the marchers

broke into the compound and set part of the house alight; Cao himself fled to

the safety of a hotel in the foreign-controlled Legation Quarter. He would not

be the last to do so: imperialism’s friends and foes alike found it convenient

to have such safe havens just a short hop away. The Chinese Minister to Japan,

who was also in the house, was less lucky and was badly beaten.1

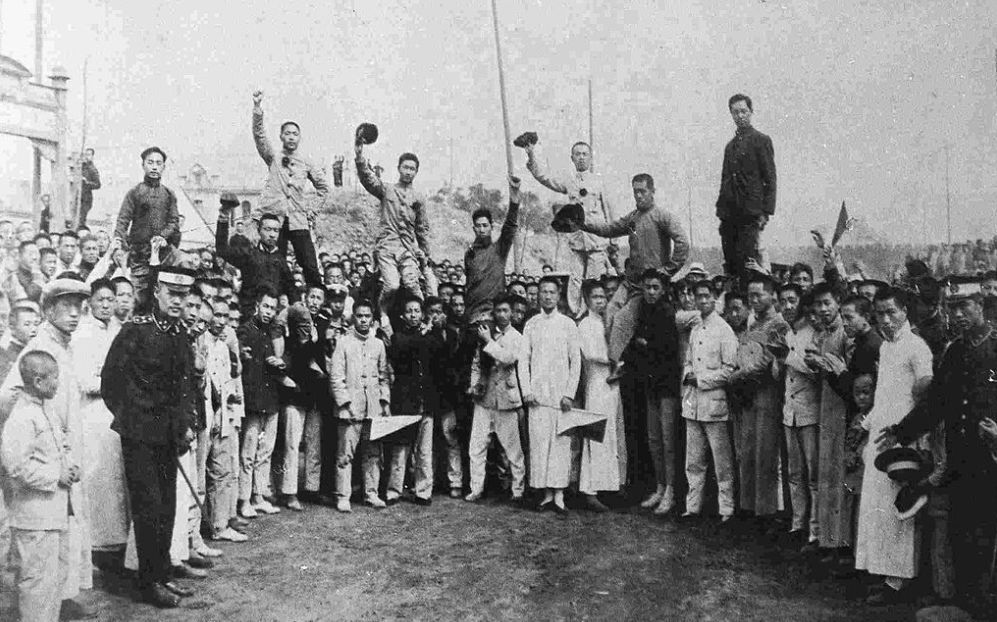

Students of Beijing

Normal University after being detained by the government during the May Fourth

Movement:

This became a

nationwide assault on imperialism and China’s prevailing culture.

Demonstrations began to be held across China, and across Chinese communities

overseas. The most potent weapon available was the boycotting of Japanese goods

or the services of Japanese firms.

Modern China’s right-left overlap

Thus modern China’s

history is not a history made by foreigners, but its domestic history was an

internationalized one, at times very heavily spiced with them.

As we have already

seen in part one nationalism has long been

ingrained in the Party’s ideology and identity, with a long historical line

connecting the Party of today with the nationalist ferment of the late Qing

Dynasty. The core theme animating the Party across that stretch is the search

for something that could restore China to its former greatness and would help

it achieve the goal of “national rejuvenation.” Today, that phrase is at the

center of Xi Jinping’s political project, but it has a deep history that has

pervaded China’s political exertions for almost two centuries.

This concept went at

least as far back as Sun Yat-sen and was invoked by almost every modem Chinese

leader from Chiang Kai-Shek to Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. In this sense,

National rejuvenation provides a sense of mission not only for China’s domestic

reforms but also for its grand strategy. Also, in the case of Xi Jinping, for

example, during a high-profile tour of an exhibit at the National Museum of

China in November 2012, shortly after he became leader of the CCP, he exhibits

at that time was called the “Road

to National Rejuvenation,” and Xi said that the Chinese Dream is the “great

rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” (中华民族伟大复兴; 中華民族偉大復興; Zhōnghuámínzú Wěidà Fùxīng).

For many years, the

orthodox view in the People’s Republic of China was that after the

demonstrations of 1919 and their subsequent suppression, the discussion of

possible policy changes became more and more politically realistic. People like

Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao shifted more to the left and

were among the leading founders of the Communist Party of China in 1921, whilst

other intellectuals, such as the anarchist writer and agitator, Ba Jin took

part in the movement.

In From Rebel to

Ruler, his new history of the CCP, Tony Saich of the Harvard Kennedy School

argues that the party also owes its survival to two much more hard-edged

institutions: its organization and propaganda departments.

Saich gives a

memorable account of a fellow Dutchman, Henk Sneevliet,

who in 1921 was sent by Moscow to liaise with Chinese Communists. Sneevliet was present at the CCP’s first meeting and was

singularly unimpressed by them, so much so that he advised against forming a

full-fledged party. Instead, he argued that progressives should first pursue

broader goals and link up with potential allies as a way to avoid destruction.

But for example,

where all Chinese should study the history of the CCP for its 100th

anniversary, the Party’s first

General Secretary, Chen Duxiu, should not be mentioned. This

whereby the bulletin Gongchandang published

in November 1920 by Chen Duxiu’s Shanghai group calling itself the Communist

Party of China was born a full eight months before

the First (CCP)National Congress.

Chinese Marxists

initially drew intellectual sustenance from their Japanese counterparts until

Japan clamped down on leftist activities. The Chinese then turned to American

and British sources. Yoshihiro Ishikawa traces these networks

through an exhaustive survey of journals, newspapers, and other intellectual

and popular publications. He reports on numerous early meetings involving a

range of groups, only some of which were later funneled into CCP membership. He

follows the developments at Soviet Russian gatherings attended by several Chinese representatives

who claimed to speak for a nascent CCP.

But not only were

there all manner of organizations and people calling themselves communist

in China in 1920-21 but there was also a right-left wing overlap. For

example, around October or November

1920, Chen Duxiu arranged an audience

for Grigory Voitinsky (who led

the first official Soviet mission to China with (nationalist)

Sun Yat-sen in the library

of Sun’s house on rue Molière, a comfortable villa in the French Concession

built by donations from Chinese who had made their money abroad.

On 25 November, Sun

left Shanghai and returned to the south, and it was here that he received his first

letter from Lenin and responded via the Soviet trade mission in London.

The Soviet Union

launched one approach to China by open, legal means and another through the

illegal underground. With the Beiyang government

t(officially the Republic of China (Chinese: 中華民國; pinyin: Zhōnghuá

mínguó), formal diplomacy aimed to secure and

fortify Russia’s geopolitical interests. The covert overtures were in the hands

of the Comintern and directed at

furthering the Asian revolution. They came to focus increasingly on

Sun Yat-sen and the south. This pas de deux was often out of step.

The first contact with Sun Yat-sen had been made in 1918 when he telegraphed Lenin from his exile in

Shanghai to express the hope for a common struggle against the European

empires that encircled them both. Lenin had no illusions about what he termed

the ‘virginal naiveté’ of Sun Yat-sen’s expressed commitment to

socialism, but he needed allies.

Sun Yat-sen’s own

crew of foreign advisors was an eclectic and internationalized one. Partly it

was used to mediate between the revolutionary and foreign officials.

The collapse of the

Shanghai peace talks in 1919 had left the southern coalition, in which the

Guomindang played a key role, even further isolated from the formal

institutions of the republic; although in a bizarre twist, from July 1919 until

March 1920, the coalition received, with the agreement of the central

government, a share of the Customs revenue surplus, Establishing

an alternative, in their eyes legitimate, the national government in Guangzhou

had failed. The wheel of fortune turned: Guangdong province was dominated

after October 1920 by a veteran revolutionary, General Chen Jiongming, who nominally served as governor, A progressive,

if idiosyncratic, reformer, much taken with anarchist philosophy, Chen’s slogan

‘Canton for the Cantonese’ reflected the hostility of local interests to the

depredations of extra-provincial troops, as well as his own federalist

leanings. Whereas Sun Yat-sen aimed to reunite the nation, Chen and an

increasing number of others wished to explore a federal solution to China’s

problems. From his base in the east of the province, Chen had moved to

expel the forces from neighboring Guangxi province who had occupied Guangzhou

and expelled Sun’s regime. Chen allowed Sun to return to Guangzhou in November

1920, and to re-establish what the Guomindang presented as the legitimate

national government of the republic, wheeling out a few hundred members of

the old parliament elected back in December 1912 who voted to make Sun

president in May 1921.

An estimated 120,000

people processed through the city on Sun’s inauguration. Chen’s troops,

schoolchildren, even martial arts practitioners and actresses had their place

in the great demonstration. Naval gunboats fired salutes from the river, and great

triumphal arches had been erected, decorated with electric lights. But after

such a heady Guangzhou spring, tensions between Chen Jiongming’s

provincial ambitions and Sun’s aim to use the province as his base from which

to launch a war of national reunification mounted. The end came in June 1922

when Sun and his government were expelled after he had stripped his host and

protector of his offices. Outgunned and outnumbered, Sun fled, and not for the

first time with foreign assistance, shipping out of Guangzhou on a British

gunboat, but not before his own gunboats had bombarded Chen’s troops,

killing civilians as they did so. Sun returned, yet again, in February 1923,

having bought the services of mercenary units from Yunnan province, who drove

Chen out. So it seemed to go, so it threatened to go on and on,

revolutionizing the French farce with rapid exits and plot changes. But it was

a dark and sanguine comedy, for lives were lost in each act, and rarely were

they those of the principals.

During his 1922-3

exile in his house in Shanghai, safely located in the French concession, Sun

was visited by Soviet emissaries, including Adolf Joffe, the USSR’s ambassador

to Beijing, building on earlier contacts. The framework for collaboration had

started to emerge. There was nothing covert about this, although the

International Settlement police had diligently watched and recorded all

they could.

Only his ejection

from Canton by forces loyal to Chen Jiongming had

persuaded him to endorse the alliance with the Communists.

In February 1923, with outside troops’ support, so-called ‘guest armies,’

Chen Jiongming was ousted from the city and

withdrew into the northeast Guangdong province. Sun Yat-sen was able

to return to establish a new government. Before he left Shanghai, after a

series of meetings at the Palace Hotel and at Sun’s mansion, on 26 January

1923, Sun signed cooperation with Adolph Joffe, the man who had led the Soviet

delegation at Brest-Litovsk.

Shanghai’s local

press documented the meetings with Joffe and the two men’s policy agreement on

26 January, just as the ground was being laid for Sun’s return to Guangzhou.

What made this encounter distinctive was that it was a record of an

understanding between a foreign ambassador to a sovereign state and one of that

state’s rebel opponents.

During this first

congress, the Kuomintang’s reorganization process to become the Kuomintang of

China in 1919 from the previous Chinese Revolutionary Party was formally

completed. A policy declaration was also drafted to fight against imperialism

and feudalism, determining three policies of alliance with the Soviet Union and

alliance

with the Communist Party of China. This first congress eventually led to

the reunification of China four years later after the Northern Expedition.

In part one we

highlighted the process by which the state incorporated the empire’s fluid

borderlands into the fixed borders that came to precisely delineate the

sovereignty of the Republic of China.

Arguably the three

most important imperial contributions to modern Chinese identity were (1) the

formation of an ethnocentric or Sinic political and

cultural community around which the new Chinese nation-state would be imagined;

(2) the massive expansion of state territory during the Manchu Qing dynasty

that established the geopolitical framework and international boundaries of the

modern Chinese nation-state; and (3) the Qing construction (building on the

Mongol Yuan dynasty) of a multiethnic empire of the Han, Manchu, Mongol,

Tibetan, and Sino-Muslim peoples that provided the foundation for

reconstituting the new Chinese nation as a unitary yet multiethnic state. The

first of these provided the basis for the invention of the Han race or

nationality (Hanzu), the ethnic majority around which

the nation was to be built and imagined. The second engendered the modern

concept of the frontier and what the Chinese nationalists would term the

“frontier question”, namely, the challenge of exerting full state sovereignty

and control over a remote zone of untamed wilderness while protecting it from

foreign encroachment. And the third spawned a new category of citizens, the

minority nationals or the marginalized and backward peoples living along the

frontiers of the nation, thereby creating for the state the problem of

classifying and assimilating these marginalized citizens into the geo-body of

the nation, what the CCP/PRC called the “national

question.”

The Chinese Ministry of

Education agency charged with promoting the Chinese language and culture

worldwide also called The Office of Chinese Language Council

International. Generously backed by government resources, it directs more

than 500 ‘Confucius Institutes’ in over 140 countries worldwide.2 The only book

on history that they recommend to its students is entitled Common

Knowledge About Chinese History. Together with its companion volumes about

geography, the series is available in at least twelve languages: from English

to Norwegian to Mongolian. This is the official ‘national history’. The theme

of the first half of the book is China’s primordial existence and a people

called the Chinese who have existed across millennia. Even when it wasn’t

called ‘China’ or was divided between rival states, it was still somehow

‘China.’ The underlying premise is continuity.

Similarly, from the

mid-1920’s onward, right-wing activists within the Nationalist Government had

insisted that the true subject of revolution was a harmoniously cooperative

national body, bound together by culture, acting in concert against a range of

internal and external threats. These struggles emerged not from a state of

relative social stability but the charged conjuncture of an ongoing

post-dynastic reordering of Chinese society and a volatile world poised

between two cataclysmic wars. Arno Mayer lias

suggested that “students of crisis politics need multi-angled and adjustable

lenses with which to examine such unsettled situations. These lenses must be

able to focus on the narrow synchronic and the broad diachronic aspects of

explosive conjunctures as well as on the intersections between them. In this

light, the Nationalist Government right wings narrowing in on Confucianism as

the cultural glue that lent the national subject its coherence can be seen in

diachronic context as a reaction against 1910s New Culture and May Fourth

Movement critiques of China’s dynastic past, in addition to a more general

rethinking of that past in the wake of imperialism.

When Chinese

delegates rejected the recommendation of the two Comintern advisers that they

forge a “united front” with capitalists and even consider joining the emerging

nationalist movement led by Sun Yat-sen to the south. Instead, the delegates

insisted on a pure “proletarian” platform that called for a surrender of land

and machines to the working masses.

The new 100 years of humiliation

Although the “century

of humiliation” is still used in CCP-initiated communications, arguably an even

more important periodization formulated by the CCP in recent years has been the

use of the slogan, “China is not the country it was 100 years ago.”

This is a clear

reworking of the century of humiliation trope and has been used, most notably by Foreign Minister

Wang Yi, to push back on

external criticism and to remind foreign audiences that China may have given in

to foreign demands in the past, but that is not the case now. The evoking of

the much infringed-upon pre-1949 China serves to contrast with China’s contemporary

major power status to further demonstrate the crucial role of the CCP in

China’s revival.

Curiously, however,

since December 2020, the slogan has been altered to “China is not the China of

120 years ago.” The most notable use of this new version came the week after

tense high-level diplomatic talks between the United States and China occurred

in Alaska. In response to the initiation of sanctions over

alleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Hua

Chunying reiterated the 120 years version of the slogan in her press briefing

to draw attention to Western powers repeating history to gang up on China.

The change from 100 to 120 years is not trivial.

As memes on

Chinese social media had

been quick to point out, there is an interesting comparison (and contrast)

between the 2021 Anchorage talks (and subsequent fallout over Xinjiang) and the

1901 Boxer Protocol meetings from 120 years earlier, when a beleaguered Qing

Dynasty was forced to sign off on huge indemnities in reparation for the Boxer

uprising against the international legations.

As the party begins

its second century, that old debate still reverberates.

Ignoring many of

these aspects of modern Chinese history the Communist Party of China, has a

history of manipulating the historical record.

For example:

Photographs were

changed to emphasize Mao’s presence or excise purge officials, and history

texts and museums were remodeled to promote the new priorities.

Reformist leader Deng

Xiaoping also tried to reinterpret history, in his case criticizing Mao’s

mistakes in starting the disastrous 1966–76 Cultural Revolution. Deng ushered

China out of the shadow of Mao’s dictatorial regime into an era of collective

leadership, under which party dominance slipped.

Yet the

hubristic rhetoric of the Party about its place in history is

laughable if not for the serious consequences this has for China’s future.

Xi is trying to

change this by updating historical narratives to increase support for the

communist rule, by concentrating power in his own hands and consolidating the

party’s control over society.

The newest edition of

official party history no longer criticizes Mao Zedong for chaos and killings

in the 1960s and ‘70s, but praises his Cultural Revolution as an

anti-corruption measure and blames the upheavals on “insufficient

implementation of his correct ideology.”

More than a quarter

of the book, which was published in February, is devoted to China’s “new

era” under Xi, in

which the “China dream” of great national rejuvenation is fulfilled. Five pages

describe the COVID-19 outbreak, praising Xi’s leadership of the response as a

demonstration of how the party always puts “the people” first.

Meanwhile, those who

deviate from Beijing’s narrative of harmony and prosperity are punished.

Many were reports by

Chinese journalists who risked their lives covering the early days of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, only to

have their articles censored as Xi pushed for “positive

energy” propaganda focused

on praising heroes, not marking human

suffering.

Cai and Chen were

detained in April 2020 and had been held for more than a year before they went

to trial. Their families were not allowed to see them, hire personal defense

lawyers for them or examine the documents explaining charges against them,

according to Chen’s older brother Chen Kun, who now lives in France.

Chen Kun makes a case

for his brother’s release outside United Nations headquarters in Geneva in

2020:

The pressure is not

only coming from officials but also from ordinary people, friends, family,

neighbors, and netizens who are increasingly reporting one

another’s speech,

especially online.

Official statistics

show that mutual tattling has increased. In 2020, China’s Central Cyberspace

Administration handled 163 million reports of improper online speech, an

increase of 17.4% from 2019. The majority came from Chinese social media

platforms including Weibo, Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent.

In April, China’s

Central Cyberspace Administration issued a new request for reports of “hazardous information involving

historical nihilism.” It offered phone, app and website options for tattling on

anyone caught “twisting” party history, criticizing party leaders, ideology or

policy, “smearing” heroes and martyrs, or speaking negatively of China’s

traditional, revolutionary or modern culture.

Mutual reporting

continued to grow, with nearly 15 million reports that month, an increase of 38.4% from March and a 2.6%

increase from April 2020.

Wall Street

Journal reports on the

proliferation of Communist Party and pro-Xi propaganda that education ministry

is inserting questions on party’s history in college-entrance exams, “to guide

students to inherit red genes,” history classes for employees on the party’s

achievements are being organized by “private businesses, law firms and even a

Shanghai temple dedicated to the Chinese god of wealth… Airlines (are staging)

in-flight singalongs and poetry recitals to teach passengers about the party’s

past.”

Alongside, Xi is

publicly administering loyalty pledges to senior party

leaders while cadres of

the 90 million strong party are simultaneously being put through an ideological

training regimen that includes undertaking tours of ‘red sites’ (party’s most

important historical locations) to foster fidelity.

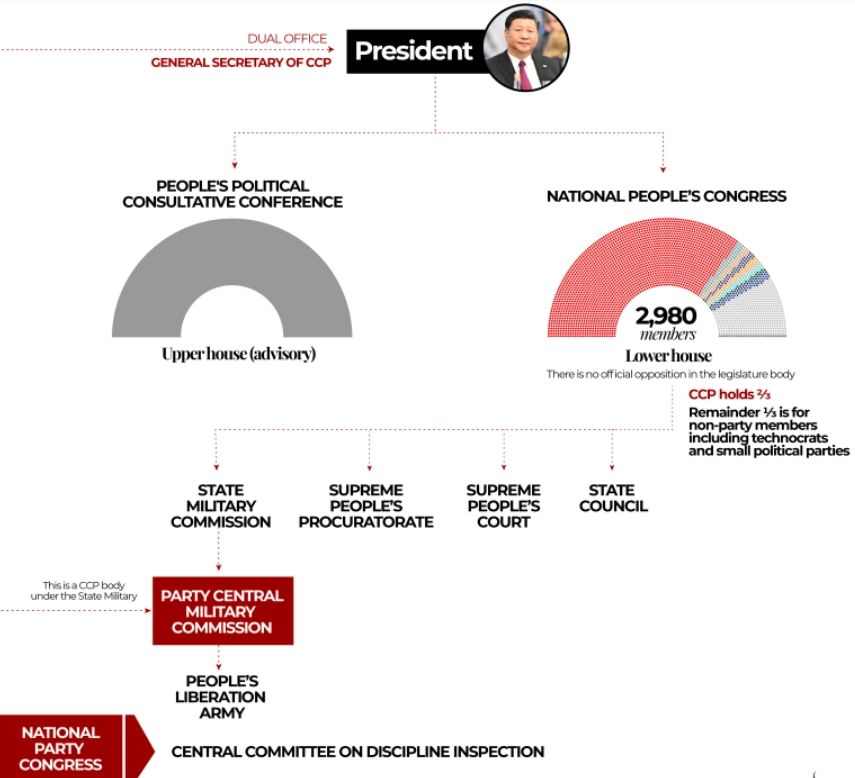

As Jamestown

Foundation senior fellow and veteran journalist from Hong Kong Willy Wo-Lap

Lam writes, “Xi has redoubled efforts to clamp down on dissent

among intellectuals and even former top cadres while also reining in leading

private entrepreneurs whose wealth and influence may detract from the

all-embracing powers of the party. Finally, Xi, who is also chairman of the

Central Military Commission (CMC) that oversees the People’s Liberation Army,

has masterminded a housecleaning of the nation’s military and police forces.”

In the run-up to CCP’s

centenary celebrations, Xi’s most urgent project has been engineering history

and whitewashing the crimes of Mao, whose social engineering project Great Leap

Forward in 1957 caused tens of millions of deaths through famine and poverty.

Mao is also responsible for the killing of another two to three million people

through his 10-year purge (from 1966-76) of “counterrevolutionaries”, a pogrom

against imagined political adversaries including elites whom Mao considered to

be a threat to his position.

As Ian Johnson writes

in Chinafile, “Mao was responsible for about 1.5 million deaths

during the Cultural Revolution, another million for the other campaigns, and

between 35 million and 45 million for the Great Leap Famine. Taking a middle

number for the famine, 40 million, that’s about 42.5 million deaths.”

Mao’s atrocities

during his tyrannical rule and the excesses of Cultural Revolution have been

documented in chronicle of party events. Not anymore. In February, Xi issued an updated version of An Abbreviated

History of the Chinese Communist Party (Zhongguo

Gongchangdang jianshi) that

airbrushed all atrocities committed by Mao. He was instead credited for

“setting the foundation of ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ and

providing ideological enrichment of the nation with “valuable experience,

theoretical preparation and material foundation” during the 1949-1976 period,”

points out Willy Wo-Lap Lam.

As expected, the new

‘history’, part of a series of books, documents and articles that sanitizes Mao

and glorifies his role, also lionizes Xi and confirms his status as the party’s

“core”. This is essential to address issues of corruption, factionalism and

disloyalty within the party because insubordination against the “core leader”

is to go against the party. This is also a natural progression of Xi’s hyper-centralisation of power which he has done by rendering the

office of prime minister almost powerless.

As Jude Blanchette

and Evan S. Medeiros write in their paper for The Washington Quarterly, former presidents

“Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao had strong partnerships with their respective

premiers (Zhu Rongji and Wen Jiabao), thus giving the State Council significant

authority over setting economic policy. Xi, on the other hand, has sidelined

premier Li Keqiang and positioned himself at the center of nearly all key

policy discussions. Relatedly, he pushed through one of the biggest political

restructurings in China’s modern history at the 2018 National People’s Congress,

with the CCP subsuming many of the governing and administrative functions that

had previously been the domain of the State Council.”

As mentioned at

the start of this overview Xi has initiated a program with the help of

technology to address “historical nihilism”. If any statements are made or any

posts are put up criticizing Communist Party leaders or their policies,

cyberspace regulators will ensure these are “cleaned”. There is also a hotline

and an online platform “for the public to denounce instances of historical

nihilism,” backed by a 2018 law

protecting the reputations of heroes and martyrs.

Coming to the present time

The core of current era US-China competition since the Cold

War has been over regional and now global order. It focuses on the strategies

that rising powers like China use to displace an established hegemon like the

United States short of war. A hegemon’s position in regional and global order

emerges from three broad “forms of control” that are used to regulate the

behavior of other states: coercive capability (to force compliance), consensual

inducements (to incentivize), and legitimacy (to rightfully command it).

For rising states,

the act of peacefully displacing the hegemon consists of two broad strategies

generally pursued in sequence. The first strategy is to blunt the hegemon’s

exercise of those forms of control, particularly those extended over the rising

state; after all. no rising state can displace the hegemon if it remains at the

hegemon’s mercy. The second is to build forms of control over others; indeed,

no rising state can become a hegemon if it cannot secure the deference of other

states through coercive threats, consensual inducements, or rightful

legitimacy. Unless a rising power has first blunted the hegemon, efforts to

build order are likely to be futile and easily opposed. And until a rising

power has successfully conducted a good degree of blunting and building in its

home region, it remains too vulnerable to the hegemon’s influence to

confidently turn to a third strategy, global expansion, which pursues both

blunting and building at the global level to displace the hegemon from

international leadership. Together, these strategies at the regional and then

global levels provide a rough means of ascent for the Chinese Communist Party’s

nationalist elites, who seek to restore China to its due place and roll back

the historical aberration of the West’s overwhelming global influence.

The Global Financial Crises

As a nationalist

institution that emerged from the patriotic ferment of the late Qing period,

the Party now seeks to restore China to its rightful place in the global

hierarchy by 2049.

The Global Financial

Crisis accelerated a shift in Chinese military strategy away from a singular

focus on blunting American power through sea denial to a new focus on building

order through sea control. China now sought the capability to hold distant islands,

safeguard sea lines, intervene in neighboring countries, and provide public

security goods. For these objectives, China needed a different force structure,

one that it had previously postponed for fear that it would be vulnerable to

the United States and unsettle China's neighbors. These were risks a more

confident Beijing was now willing to accept. China promptly stepped up

investments in aircraft carriers, capable surface vessels, amphibious warfare,

marines, and overseas bases.

The Global Financial

Crisis furthermore caused China to depart from blunting strategy focused on

joining and stalling regional organizations to a building strategy that

involved launching its own institutions. China spearheaded the launch of the

Asia Intrastiaicture Investment Bank (AIIB) and the

elevation and institutionalization of the previously obscure Conference on

Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA). It then used these

institutions^ with mixed success3 as instruments to shape regional order in the

economic and security domains in directions it preferred.

The Global Financial

Crisis also helped Beijing depart from a defensive blunting strategy that

targeted American economic leverage to an offensive building strategy designed

to build China’s own coercive and consensual economic capacities. At the core

of this effort were China’s Belt and Road Initiative, its robust use of

economic statecraft against its neighbors, and its attempts to gain greater

financial influence.

Beijing used these

blunting and building strategies to constrain US influence within Asia and to

build the foundations for regional hegemony. The relative success of that

strategy was remarkable, but Beijing's ambitions were not limited only to the

Indo-Pacific. When Washington was again seen as stumbling, China's grand

strategy evolved, this time in a more global direction.

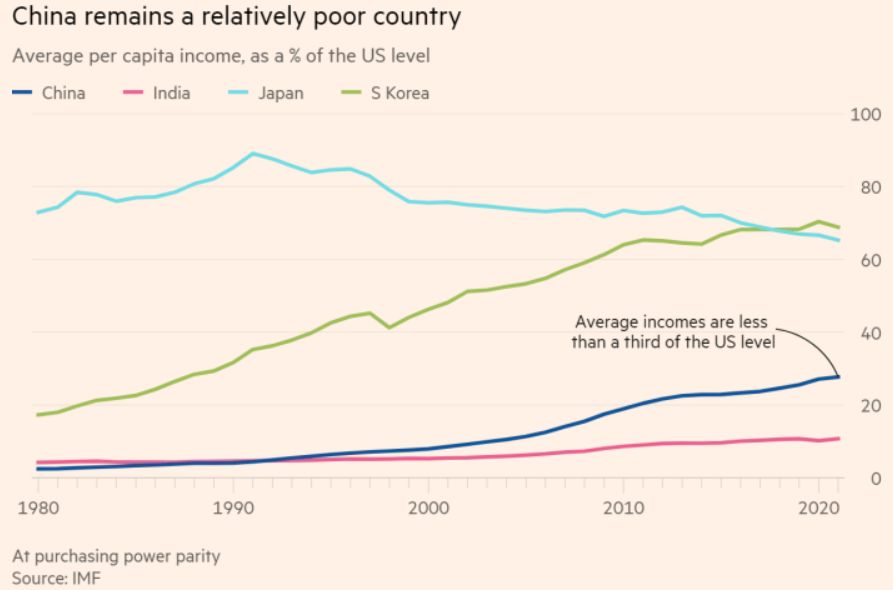

Pragmatism,

particularly on economic policy, ushered in a wave of investment that helped

the gross domestic product grow nearly 50 times since Mao’s death in 1976.

China’s economy is now poised to overtake that of the U.S. within the decade, eradicating extreme poverty and creating a new

ultra-rich class: At the end of 2019, China had 5.8 million millionaires and

21,100 residents with wealth above $50 million, more than any country except

the U.S.

During the time

consisting of Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the West's poor initial

response to the coronavirus pandemic.

In this period, the

Chinese Communist Party reached a paradoxical consensus: it concluded that the

United States was in retreat globally but at the same time was waking up to the

China challenge bilaterally. In Beijing's mind? great changes unseen in a century”

were underway, and they provided an opportunity to displace the United States

as the leading global state by 2049? with the next decade deemed the most

critical to this objective.

Politically, Beijing

would seek to project leadership over global governance and international

institutions and to advance autocratic norms. Economically, it would weaken the

financial advantages that undeniable US hegemony and seize the commanding heights

of the "fourth industrial revolution." And militarily, the PLA would

field a truly global Chinese military with overseas bases around the world.

Conclusion

Some of the

strategies to achieve this global order is already discernable in Xi's

speeches. Politically, Beijing would project leadership over global governance

and international institutions, split Western alliances, and advance autocratic

norms at the expense of liberal ones. Economically, it would weaken the

financial advantages that underwrite US hegemony and seize the commanding

heights of the "fourth industrial revolution” from artificial intelligence

to quantum computing, with the United States declining into a

"deindustrialized. English-speaking version of a Latin American republic,

specializing in commodities, real estate, tourism, and perhaps transnational

tax evasion.”8 Militarily, the force with bases around the world could defend

China’s interests in most regions and even in new domains like space, the

poles, and the deep sea. The fact that aspects of this vision are visible in

high-level speeches is strong evidence that China’s ambitions are not limited

to Taiwan or too dominating the Indo-Pacific. The “struggle for mastery,” once

confined to Asia, is now over the global order and its future. If there are two

paths to hegemony, a regional one and a global one, China is now pursuing both.

This is a template China has followed.

With Japan, the U.S.,

and Europe continuing to struggle to pull out of the COVID-19 crisis, China

appears to stand out as the sole winner.

Understood by the

Biden administration, It shows that Beijing would seek to project leadership

over global governance and international institutions and advance autocratic

norms. Economically, it would weaken the financial advantages that underwrite

US hegemony and seize the commanding heights of the 'fourth industrial

revolution. And militarily, the PLA would field a truly global Chinese military

with overseas bases around the world. And so that is what also as we have seen,

the discussion about Taiwan become about.

As for the

so-called Quad, the FT reported that the

Quad is a delusion as the new grouping won’t give the United States any

more leverage over China than it already has.

For a long time,

China was mostly on the defensive instead of taking the offensive on the human

rights issue. Oftentimes, it does not have the upper hand when its opponents

attack because of its weak national strength and large population of poor

people. But today, China has achieved great success in poverty alleviation. Its

economy rebounded quickly after containing the Covid-19 pandemic, and the

people’s morale has been greatly boosted as well. This gives the government the

confidence to fight back against the West.

The country will

surpass the U.S. in terms of nominal GDP in 2028, according to a December

forecast by the Japan Center for Economic Research. Before the pandemic, China

had been expected to become the world's biggest economy in 2036 at the

earliest. The change suggests that ironically, the pandemic, which started in

China, is actually reinforcing the country's strength.

1. C. F. Yong and R.

B. McKenna, Kuomintang Movement in British Malaya, 1912–1949, Singapore,

National University of Singapore Press, 1990.

2. Xinhua, ‘Over 500

Confucius Institutes Founded in 142 Countries, Regions’, China Daily, 7 October

2017, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2017-10/07/content_32950016.htm

For updates click homepage here