By Eric Vandenbroeck

10 Dec. 2018

Yesterday Belgium’s

notorious Africa Museum in Tervuren reopened to

the general public after a five-year renovation.

Still officially

called the Royal Museum for Central Africa, but better known as the Africa

Museum, it cannot help but ooze colonial triumphalism, despite recent

protestations of egalitarian diversity. Housed in a majestic purpose-built

palace 20 minutes’ drive east of Brussels, it stands above a lake amid

parkland. Immaculate gravel paths sweep around the site. However radically the

interior may have been refashioned to reflect new attitudes to Africa, the

grandeur of King Leopold II’s design and the fervour

of his desire to promote his imperial venture into the continent’s heart still

overwhelm the visitor. The monarch ruled Congo as a private estate nearly 80

times bigger than his European homeland from 1885 until a year before his death

in 1909; his double-L motif is embossed on almost every wall and above many an

alcove.

Just a few hundred

meters from where 267 Congolese villagers were kept behind fences bearing

"Do

Not Feed" signs, Brussels' Africa Museum is trying to make peace with

that history.

This is currently a

huge challenge for director Guido Gryseels, who now

attempts to put Belgium’s colonial abuse in its context in the very museum that

the chief perpetrator of the horrors of Congo had built for his own glory and

whose dark legacy has long remained shielded from full scrutiny.

He also said that

colonialists have long regarded the museum as a haven of nostalgia. “For them,

this is their home and they are very nostalgic about this place,” Gryseels said. They see Belgium’s role in Congo as benign:

building roads, providing health care, spreading Christianity and giving Congo

a standard of living few others in Africa had at the time.

“They’re a bit

disappointed about the critical view,” he said.

Though he never

visited his private colony, let us be reminded, King Leopold gained

the Congo from deception and not persuasive techniques and held absolute

political, judicial and legislative power in the Congo.

All 'unoccupied' land

was claimed as the property of his Association, both unexplored lands, and fields

lying fallow. Even settled farmlands were subject to his orders. Leopold also

claimed a large private estate in the region of Lake Leopold II (north-east of

Kinshasa). Meanwhile, Leopold also set about confusing the question of

legitimacy. In place of the old International African Association, which became

moribund, Leopold constructed a new International Association of the Congo.

Holding power always in his own hands, but often in the name of this distinct

corporation, with its own flag, Leopold was also able to mask his private

empire with some of the veneers of his former 'humanitarian' promises. In order

to fund the project of colonization, the Association took control of the rubber

and ivory trades. Much of the land was given to concessionary businesses, which

in return were expected to build railroads or simply to occupy a specific,

disputed region. Concessions were granted the power to tax Congolese villages

at rates of between 6 and 24 francs annually per head, an almost meaningless

figure in a country where there were no large stocks of cash in circulation.

Africans then had to work to produce crops in kind. Companies were also set up

to exploit the mineral resources, as well as human labor. The Union Miniere du Haut-Katanga, established in 1905, was soon

joined by the Compagnie de Fer du Congo, the Compagnie du Katanga, the

Compagnie des Magasins Generaux,

the Compagnie des Produits du Congo, the Syndic at

Commercial du Katanga, and so on. Many of these were owned directly by Leopold,

or indirectly, through his appointed proxies.

But one would be

wrong to assume that all Africans were repulsed by the old museum. When

Congolese-born Aime Enkobo

moved to Brussels and wanted to show his children his heritage, he came to the AfricaMuseum.

“For me it was to

show them our culture. What artists did, created, the aesthetics, to explain

that. It is what interested me. It was not the images that showed that whites

were superior to blacks .... My kids asked me no questions on that,” Enkobo said.

Still, controversy is

increasingly commonplace, and it has come from Belgians as well as the

Congolese diaspora here.

Critics have

increasingly questioned street names honoring colonialists, and statues have

been given explanatory plaques highlighting the death and destruction

colonialism spawned. A sculpture of Leopold II has had its bronze hand chopped

off, and another was targeted with rude graffiti last year.

A lot of work is

left. “You won’t find a town or city in Belgium, where you don’t have a

colonial street name, monument or plaque. It is everywhere,” said activist

and historian Jean-Pierre Laus.

He was instrumental

in getting one of the first explanatory plaques next to a Leopold statue in the

town of Halle, just south of Brussels, almost a decade ago. Instead of

glorifying the monarch, it now reads: “the rubber and ivory trade, which was

largely controlled by the King, took a heavy toll on Congolese lives.”

Instead of damaging

or destroying statues, Enkobo has created a new one,

right in the main hall of the new Africa Museum. It is a huge wooden lattice

profile of a Congolese man, looking proudly, perhaps defiantly, at the condescending

colonial statues all around him.

“I didn’t want to

respond to the negative with something negative,” the artist said in his

studio. “It is easy to destroy -- but have we thought of the others and

history? It is interesting to leave traces.”

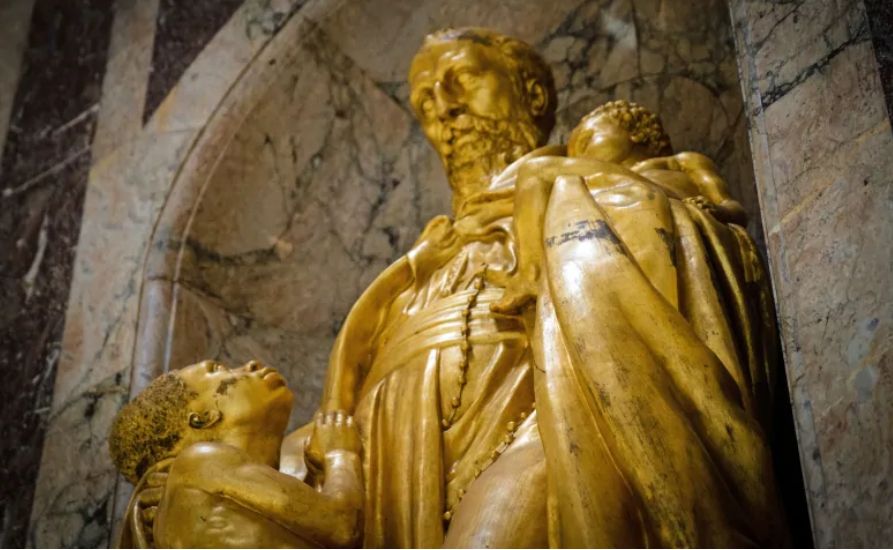

The controversial golden statue (full image see

underneath on the left) still stands of a European missionary with an African

boy clutching his robes along with a plaque that reads: “Belgium bringing

civilization to Congo.” But a modern sculpture by Aime

Enkobo (see underneath on the right) has been added

in the middle of the rotunda to centralize Africans.

I (E.V.) did visit

the museum myself in 2003, the year an initial renovation proposal was

presented to the press. At that time I was working on a related seminar and had

also posted on my website how Leopold II promoted

his Congo project. That same year I also posted what by now might seem a

somewhat controversial look at the Rwandan Genocide.

The person who

brought me to the museum by private car (as a first-time visitor one will

notice that the Museum is somewhat secluded) had spent his childhood in the

Belgian Congo and just recently has also been interviewed in context of the

Belgian "Children of the Colony" TV series. In fact, I did

communicate with him today (10 Dec.) when I decided to write this article

mentioning to him the "Belgium’s Africa Museum Had a Racist Image. Can It

Change That?" article and he answered, "Thanks Eric I agree with

this and have commented (in a similar vein) about this before."

As Guido Gryseels also said it is an emotional issue for many

Belgians, who

will have had relatives who worked in Congo in one form or another over the

years.

Thus Gryseels expects a "very mixed" reaction to his

institution's attempt to reconcile this past, and that African communities may

say it doesn't go far enough toward decolonialization, that there should be

much more awareness about the violence perpetrated against their people.

On the other hand,

the director told

DW, "a lot of [Belgians] went there with a lot of idealism. Obviously

there's been thousands of doctors who went to Congo who worked in very

difficult conditions, vaccinating children, helping women to deliver, building

hospitals and dispensaries. You can't really say that they were racists on a

negative mission."

We also should not

forget that the now so absent Belgian Royal Family was publicly protesting the

findings of Adam Hochschild's haunting best-seller, King Leopold's Ghost. And

the Belgian

government next denounced a BBC Four documentary with Louis Michel a Member

of the European Parliament and the father of Charles Michel,

the current Prime

Minister of Belgium. saying Leopold was “a true visionary for his time – a hero”.

In fact in 2005 also

director Guido Gryssels himself said that one simply needed to

“contextualize” the “allegations” by Hochschild and debates over the misplaced

use of the term “genocide” in the Leopoldian colonial

past.

Thus the Royal Museum

for Central Africa has long been

accused of complicity in perpetuating the distorted history of the likes of

Charles Michel.

But things started to

change, in 2015 when the Belgian Government wanted to honor King Leopold II the

event now was considered

a “bad idea” by a number of organizations.

In fact we fully know

today that as a result of King Leopold II‟s colonization of the Congo Free

State and then Belgium’s annexation of the Congo from Leopold, the

Congolese were left with little to no ability to successfully rule over

themselves. After a series of revolts, Belgium finally granted the Congo

its independence in 1960. However, when independence came there were less than

30 university graduates in the Congo. Hochschild states, “There were no

Congolese army officers, engineers, agronomists, or physicians.” Thus they had

no people who were specialized in military affairs, construction, farming, or

healthcare which are all vital to any government. Furthermore, Hochschild

notes, “The colony's administration had made few other steps toward a Congo run

by its own people: of some five thousand management-level positions in the

civil service, only three were filled by Africans.” Only three Africans out of

millions in the Congo had administrative experience. This is a dilemma because

it hinders the growth of businesses as there is no one who could lead them.

The policies of King

Leopold II allowed for future rulers like Mobutu and the Kabila’s to dictate

over the Congo and further extract its resources.

Thus King Leopold II,

through his ability to deceitfully acquire the Congo using philanthropic

smokescreens and his ability to institute extensive forced labor resembling

slavery, he set the stage for the Congo’s ethnic, political, and economic

turmoil. His actions helped disband some of the Congo’s most powerful kingdoms

like the Luba, Lunda, and the Kongo. These kingdoms provided stability to a

vast region and maintained an efficient administration that was connected to even

the smallest of villages through councils for provinces, districts, and

chiefdoms. With the annexation of the Congo by Belgium, which was only possible

through Leopold’s previous ownership, they disbanded more tribes and as stated

would cause massive ethnic wars among the many ethnic groups competing for

power in the Congo’s independence of 1960.

Politically, Leopold

ensured that the Congolese would not have a chance at self-rule for over a

century. Belgian rule lasted for almost 60 years and continued the policies of

Leopold. They granted land to concession companies, who all together extracted

billions of dollars worth of resources that were

never paid back. The Congolese were deprived of any positions in the

administration and due to a lack of education would almost be inept at

self-rule from the lack of training. The transition to Mobutu after Belgian

rule also put the Congo in decades of dictatorial rule. Although Joseph Mobutu

or Mobutu Sese Seko was born in the Congo, he was very much a puppet for the

Western powers who assassinated the publicly elected Lumumba in 1961 to put him

there. Then with the Kabila family in power today, it looks like the Congo is

following the same political repression and lack of civil rights and equality

that existed in Leopold’s Congo Free State. The Congo was never given the

chance of having a representative democracy where people could vote for

candidates who in turn would serve their best interests. Instead, due to

Leopold’s rule, the Congo was placed in a quagmire of authoritarian rule and

dictatorships which continue to prevail.

Economically, the

Congo has suffered more than most states. Leopold created a policy of forced

labor and those laborers were paid next to nothing for their hard work. The

Congo was turned into an enclave economy that was solely developed for

extraction of resources. Belgium also made the Congo a plantation economy

demanding huge quantities of crops especially during World War I and the Great

Depression. This, in turn, forced the Congo to take loans from Belgium to pay

for their own resources. Yet, combined with interest, these loans could never

possibly be paid back without a functioning domestic economy. As Leonard and

Strauss mentioned above, with an enclave economy, Leopold, Belgium, Mobutu, nor

the Kabila’s would have to provide for domestic production or social

institutions as the wealth of the people were not in relation to the wealth of

the state. Without an effective job industry, the Congolese could never pay

back the debt inherited by early Belgian rule. Therefore, according to the

dictators, reforms were unnecessary and hence the Congolese continued to be

subjugated by poverty.

It was as recent as

2017 that U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley on Friday that this authoritarian nation

holds delayed national elections in 2018, saying

continued international backing for a nation that hosts the largest United

Nations peacekeeping mission is at stake.

One could also argue

of course Belgium’s “great forgetting”, as Hochschild terms it, was not always

an accident. In the years before 1908, Leopold instructed the burning of state

archives, telling an aide: “I shall give them my Congo, but they have no right

to know what I have done there”. For much of the rest of the twentieth century,

attempts to investigate

the history of the Congo Free State were fiercely suppressed. Until the 1980s,

Jules Marchal, leading historian and former

Belgian Ambassador, was

prevented from accessing papers held in Foreign Ministry archives, despite

having diplomatic clearance. Others writing on the topic reported receiving

threatening anonymous letters and having their lectures interrupted by former

colonial officers.

But Guido Gryseels, who has been masterminding the changes, now

insists he will "decolonize" the museum in form and message,

delivering a more honest narrative to the Belgian public. "That the Congo

was not the story of bringing civilization, that it was not a story of

eliminating the slave trade, that it was a story of brutal capitalism, looking

for resources, looking for profits."

Today problematic images like the above are stored in a barricaded

section without descriptions titled: “A Museum in Motion.”

For

updates click homepage here