Meanwhile in the USA,

the weakness of the Bush administration clearly is not ending. Bush seems to be

acting decisively, until one considers how small his room for maneuver actually

is. These things happen periodically in the United States. Presidents Nixon,

Johnson, Truman -- all ended their years in office unable to wield power. The

United States always recovers from this. Nevertheless, such cycles in the

presidency create opportunities for other powers to act. Whenever the world's

leading power moves toward political paralysis, others become much more

aggressive. We see this and will continue to see this in places from Venezuela

to Asia. But the most important actions will be taken by the great powers,

Russia and China.

Russia has clearly

reasserted itself. The state is now the center of both Russian society and

economy. Russia now clearly intends to return to being the center around which

all former Soviet states revolve. Moscow has discovered, not surprisingly, that

energy and other natural resources provide it with a tremendous lever in the

region. That, plus the ubiquitous Russian intelligence service, allows the

Russians to shape the region. At the moment, given U.S. preoccupations, the

response of the Americans to the Russian resurgence has not been substantial.

The Russians would not be deterred anyway; for them, this is a matter of

fundamental national interests. But they also need not be concerned: The United

States has neither the appetite nor bandwidth for resistance.

The consolidation

trend will continue and increase in 2007, as Russia prepares for the Dec. 2

parliamentary elections and the presidential election March 2, 2008. Expansion

of state control over the oil, natural gas, gold, diamond and metals industries

will be coupled with the consolidation of political forces and a crackdown on

dissent. The deaths of former Russian Federal Security Service agent Alexander

Litvinenko and journalist Anna Politkovskaya have been attributed to their

outspoken opposition to the Kremlin, and others could vanish from the political

scene one way or another as elections draw near. Because Russia 's electoral

laws have been changed to favor larger and more established parties, many

smaller groups will seek to coalesce into larger entities. The pro-Kremlin

United Russia party is expected to take most of the seats in the parliament,

thereby gaining the ability to alter the constitution, and the opposition

forces remain weak and unable to unite into a viable force. The new parliament,

much like the current one, will exist solely to implement the president's will.

Putin will select a

successor, and the two front-runners for that position -- First Deputy Prime

Minister Dmitry Medvedev and Defense Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Sergei

Ivanov -- will expand their public roles in 2007. The two men have been exhibiting

pragmatic foreign policy outlooks, as we indicated in our previous annual

forecast. Putin will not make his choice until the last possible moment, and

though he could choose another candidate, Medvedev and Ivanov are the current

favorites. Putin will remain in a position of power, either by retaining the

presidency with the help of the newly elected parliament or by assuming control

over a strategic industry such as natural gas.

Internal

consolidation will remain closely tied to Russia 's expanding control over its

periphery. Moscow has had considerable success reasserting its influence in

Ukraine following the March parliamentary elections and the installation of

Viktor Yanukovich as prime minister. We indicated in our previous annual

forecast that Russia was likely to act to install a friendly regime using the

election as a key event, though we did not predict that Ukraine would return to

the Russian fold to the degree it did in 2006. Following the Orange Revolution

of 2004, pro-Western forces gained control under President Viktor Yushchenko,

though they have not been altogether successful at actually governing Ukraine.

Russia 's public support of Yanukovich as a presidential candidate in 2004 was

unsuccessful, but with Moscow 's behind-the-scenes support, Yanukovich's Party

of Regions won a plurality in 2006 and, after months of wrangling, managed to

form a majority coalition in the parliament.

Since then, Ukraine

has remained in deadlock, with the executive and legislative branches

continuously working to undermine each other and doing little actual

policymaking. Yanukovich has been more successful in this row and has undercut

much of Yushchenko's authority. Yushchenko has but one chance to regain

control, and it is not a good option -- to dismiss the parliament and call

early elections. In order for Yushchenko to retain a vestige of power, he will

need to rekindle the Orange Coalition with ambitious former ally Yulia

Timoshenko, but that would mean Yushchenko would have to share the spotlight

with her.

Ukraine 's neighbor

Belarus has experienced a significant deterioration of relations with Russia

over the past year. A last-minute deal for supplies of Russian natural gas

signaled an end to Russia 's subsidization of President Aleksandr Lukashenko's

regime.

In order to avoid

becoming a complete peon of the Kremlin, Lukashenko will have to look westward

for investment and support, and this option gives him at least some leeway

against Moscow. Belarus has been beholden to Russia for Lukashenko's entire

13-year presidency. The country is now at least somewhat in play, but Russia

still has the tools to counter Belarus ' Western ambitions. The oil cut-off on

Jan. 8 signaled Russia 's willingness to inflict damage to its own economy in

order to bring the wayward republic under control.

Tensions are set to

escalate in the Caucasus, as relations between Georgia and Russia show no signs

of improving, and as Armenia and Azerbaijan inch toward an escalation of the

Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. As Tbilisi further extricates itself from economic

ties to Moscow, the conflict over Georgia 's two secessionist regions, South

Ossetia and Abkhazia, will intensify. The United Nations is almost certain to

grant independence to the Serbian province of Kosovo; this will prompt Russia

to call for the same status for secessionist entities outside its own borders.

Russia is likely to seek to increase its presence in Abkhazia and South Ossetia

under the guise of peacekeeping efforts, and Georgia will respond in kind.

Azerbaijan has

significantly increased its income from energy projects and has pledged to

spend approximately $1 billion on defense in 2007, up from $700 million in

2006. Although Azerbaijan 's military has been inferior to Armenia 's, the

spending hike could bring increased confrontation between the two over the

Armenian-controlled Nagorno-Karabakh region in Azerbaijan. As with Georgia 's

secessionist regions, the determination of Kosovo's status will prompt an

escalation in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. A diplomatic solution is not

likely in the near future.

Russia historically

has dominated Central Asia, with most of the countries -- especially regional

leaders Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan -- ruled by Soviet-era cadres with allegiance

to Moscow, and the others deferring to their giant neighbor anyway. At the end

of 2006, Russia gained an opportunity to expand its influence further. The Dec.

21 death of Turkmenistan 's president-for-life, Saparmura

Niyazov, another Soviet-era leader, has prompted Russia, China and other

regional players to attempt to project greater influence in the energy-rich

state. Acting Turkmen President Gurbanguly Berdimukhammedov

is the certain winner of the Feb. 11 poll, but the shape of his agenda remains

unclear, since not much is known about the man. While neighboring Kazakhstan

and Uzbekistan will want to assure that Turkmenistan is friendly, or at least

innocuous, Russia has a keen interest in maintaining control over Turkmenistan

's natural gas deposits -- the fifth-largest in the world. If the new president

is unwilling to cooperate with Moscow, the Kremlin will use its available tools

-- ranging from political pressure to assassination -- to ensure that he will

not hold office for long.

As Russia moves to

solidify its presence in Central Asia via Turkmenistan, neighboring states,

especially Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, will become increasingly concerned for

their own sovereignty. While Kazakhstan remains politically loyal to Moscow, it

has economic partnerships -- particularly in the lucrative energy sector --

with companies from many other countries, including India, South Korea, China

and the West. Should Astana grow disconcerted by Moscow's encroaching presence,

the Kazakh government could seek to counterbalance Moscow and expand its

relationship with Beijing via Kazakhstan's new Chinese-educated Prime Minister

Karim Masimov -- and China is certainly looking to increase its influence in

Central Asia.

Uzbek President Islam

Karimov is also likely to be concerned for his regime as Russian influence

expands. Karimov might continue giving Russia control of energy assets in order

to preserve his own rule, while keeping open the option to turn to China. However,

as long as the Russians do not employ heavy-handed tactics in Turkmenistan,

Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan both will seek to perpetuate their existing

relationships with Moscow.

Russia also has been

looking to expand its influence in Africa. Closer relations are likely in 2007,

as Moscow forgives African countries' Soviet-era debt and looks to increase

cooperation in the mining sector. As Russia consolidates control over its own

industries, expanding into Africa and other regions could be the next step

toward increasing control over the world's deposits of high-value commodities.

But for this to work, Moscow has to do something in Africa that it has been loathe to do at home: invest its own money. Should Russia

do that, Moscow could gain a lot of assets -- and influence -- very quickly.

Russia will attempt

to maintain the status quo in its relations with the United States and Europe

in order to focus on domestic issues. However, Moscow will continue to

cooperate with Iran, Syria, the Hamas-led Palestinian government and other

regimes considered unfriendly to the United States. In these relationships,

Russia profits from arms and equipment sales and derails U.S. goals in the

Middle East while dividing Washington 's attention. Relations with European

leaders are not likely to see improvement; German Chancellor Angela Merkel will

make European energy security a priority of Germany 's EU presidency, and

whoever is elected the next French leader will not view Russia in the same

favorable light as President Jacques Chirac has.

But the Russians will

not be solely concerned with what they call their near abroad. They are masters

of leverage, and they know the United States is bogged down in Iraq and the

Muslim world. They have made it clear to the Americans that it cannot be assumed

that Russia will simply support the U.S. position on international issues.

Moscow 's position on Iran and Syria has been unacceptable to the United

States. But then, Washington 's position on Ukraine and Georgia has been

unacceptable to the Russians. The Russians will continue to exacerbate problems

for the United States in the Muslim world. They want to limit American power,

and they will use such means to do so. And thus finally from China to the

Middle East;

The Chinese are

looking inward primarily. Their problem is internal, with a huge overhanging

portfolio of nonperforming and troubled loans. A conservative estimate is that

bad loans in China equal about 40 percent of gross domestic product. A more

reasonable estimate is about 60 percent. These numbers closely resemble those

of Japan in 1990 and tower over those of South Korea or Taiwan in 1996. The

Chinese have huge currency reserves -- but then so did Japan, South Korea and

Taiwan. Those reserves historically have not stabilized Asian banking systems

when the consequences of undisciplined lending come home to roost. Chinese

enterprises have used exports -- as did Japan and South Korea and Taiwan -- to

maintain cash flow to pay loans. But surging profitless exports merely

exacerbates the problem. The Chinese government tried to stop the runaway train

in 2006; it failed to do so. Westerners have again confused high growth rates

with economic health, as they did with Japan and East Asia . But where rates of

return on capital are extremely low or even negative, high growth rates are a

symptom of disease.

China 's financial

system already has changed dramatically from the way it was a few years ago.

Internal lending and financing patterns have shifted, and foreign direct

investment -- excluding money being recycled by the Chinese -- has declined

substantially. Many deals that were launched with high expectations five years

ago are facing substantial problems or failure. But the most important changes

in China can be seen in their politics. The Communist Party chief in Shanghai

and hundreds of his allies have been arrested for corruption. Incidents of

resistance to land seizures have increased, bringing with them violence and

arrests. The Party has reasserted itself as the master of the state, and the

Chinese security services have increased their intrusiveness and vigilance. In

China, putting off the reckoning as long as possible and controlling the social

and political consequences as efficiently as possible are the orders of the

day. Beijing is trying to regain control of the economy -- but it is more likely

to do so through political power than through economic processes.

For Westerners, the

question on China is, when will it crash? For the Chinese, the question is, how

do you save the Party apparatus in the face of enormous economic and social

stress? It should be recalled that Japan did not just fall apart one day. It experienced

an enormous growth surge, followed by a managed decline of growth in which the

pain was distributed economically. For China, the problem is the failure to

slow growth. This failure has told the leadership that they need to increase

the power of the state, and of the Party over the state. In a hundred ways,

that is happening.

At the same time,

China is becoming more insecure about its geopolitical position. Issues ranging

from trade disputes to Taiwan are being exacerbated by the insecurity that

clearly is being felt by Beijing. The regime sees the United States as a threat

to its security over the long term, and is taking steps to assert itself

against the United States. China 's lasers hit U.S. satellites last year as a

demonstration of prowess, and a Chinese submarine penetrated the perimeter of a

U.S. carrier battle group. China is not about to undertake military adventures

in 2007, but it also is not prepared to be a passive onlooker in the Pacific.

There will be more friction.

The United States,

Russia and China are the active great powers. The Europeans and Japan remain

largely passive and reactive. They will not be shaping the global environment

in 2007. Latin America will churn and shift, but there is no decisive event

coming there. Africa remains what it has been. Thus, 2007 will be a year for

great powers -- and for that matter, for those who would challenge great

powers, particularly the United States.

Plus foremost of

course the U.S.-Iranian standoff over the fate of Iraq will have a profound

impact on the course of geopolitical events in 2007. After the 2003 U.S.

invasion of Iraq, Iran seized the opportunity to assert itself as the regional

kingmaker while the United States became increasingly paralyzed in Iraq. The

United States now finds itself at a critical juncture: It no longer can afford

to stay the course in Iraq and dedicate U.S. troops to an unattainable mission

of securing the country solely through military force. As advocated by the

Baker-Hamilton report, the time has come for the United States and Iran to stop

giving each other the silent treatment and work toward a comprehensive

settlement for Iraq.

But the United States

is still far from its desired negotiating position, and thus will continue to

shy away from the Baker-Hamilton report's recommendations until it can level

the playing field against Iran. Before Washington moves forward on the diplomatic

front, it will need to disprove the perception that the United States has been

permanently marginalized in Iraq and ultimately will have to withdraw its

forces -- something that would leave Iran to pick up the pieces and project

Shiite influence into the heart of the Arab world. This perception of

marginalization is what has driven heightening Sunni concerns that United

States no longer will be the security guarantor against an empowered Shiite

bloc, led by Iran.

To shatter these

expectations and demonstrate that the United States is still very much in the

game, U.S. President George W. Bush announced Jan. 10 a strategy to

"surge" U.S. troops in Iraq. The increase will total 21,500 troops,

with a peak of 17,500 in Baghdad and another 4,000 in Anbar province.

Ultimately, this looks unlikely even to bring the total level of U.S. forces to

their peak strength of 160,000 -- the number of troops that were in Iraq in

November and December 2005, in the buildup to the general elections Dec. 15. It

is likely to be accompanied by a shift in tactics to focus more specifically on

counterinsurgency operations.

The forces will

certainly be useful -- assisting with security inside Baghdad and leaving units

that would otherwise be shifted to the capital available to confront issues in

their respective areas of responsibility. However, in and of itself, this new deployment

will be insufficient to turn the tide in Iraq. Operation Together Forward --

the failed attempt after Abu Musab al-Zarqawi's death to use a small surge in

troop levels in Baghdad to impose security there -- is a case in point.

Together Forward was essentially the U.S. military's last, best effort to

secure Baghdad with the existing force structure.

Baghdad remains the

key. Without stability there, there can be no Iraqi state. But the proposed

surge of 21,500 troops -- without a new, concerted diplomatic effort -- is

unlikely to succeed in effecting a political resolution in Baghdad.

However, there is a

key psychological element to this strategy. The United States will spend the

coming months taking an aggressive stance against Iranian operations in Iraq,

including additional raids on Iranian diplomatic offices and arrests of Iranian

officials in the country who are suspected of orchestrating attacks against

U.S. and Iraqi forces. The U.S. military will be posturing to dispel the

Iranian perception that the battleground will remain within Iraq 's borders.

The United States could also step up covert efforts to ramp up the militant

activities of Iran 's indigenous separatist groups, such as the Ahvazi Arabs in the oil-rich province of Khuzestan in

western Iran. Coinciding with U.S. moves, Israel will accelerate its own

psychological warfare campaign, using a variety of leaks and denials to heavily

publicize Israeli military plans to strike Iranian nuclear sites. By upping the

ante against Iran, the United States is placing a critical bet that the

Iranians will reconsider their Iraq strategy and come to the negotiating table

rather than risk a serious miscalculation.

To go along with the

troop surge, the United States will focus on rearranging the Iraqi Cabinet to

try to create a stronger, more functional government in Baghdad. This will

involve sidelining allies of Shiite rebel leader Muqtada al-Sadr and bringing

in a stronger Sunni presence, which will undoubtedly be a complicated and messy

affair. Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki also could resign in as little as

four months, triggering a struggle for power and a substantial flare-up in

intra-Shiite frictions over his replacement. By the year's end, Iraq 's largest

and most influential Shiite party, the Supreme Council of Islamic Revolution in

Iraq, might be better able to solidify its position in the government.

Iraq is unlikely to

split up into federal zones in the coming year, but neither will it behave as a

coherent state entity. Violence will escalate on all sides: Shiite, Sunni,

jihadist and even Kurdish, with the Sunni-Kurdish fault line in northern Iraq

becoming active toward the end of the year, as the Kirkuk referendum issue

approaches.

For its part, Iran

has been keen to bring the Americans to the negotiating table on its terms. It

wields the ability, through militants, to manipulate the security situation in

Iraq and thus to keep an effective government from taking power in Baghdad, but

it lacks the means to impose a government of its own creation there. Tehran

will focus this year on increasing the political and military costs of the

United States remaining in Iraq -- by lending more support to militants there,

including Shiite gunmen and segments of the Sunni insurgency -- but ultimately,

given the limitations and uncertainties on both sides, it is possible that a

political settlement of sorts, however weak and tenuous, will be forged in

2007.

Iran will also use

this year to push its nuclear agenda forward. The U.N. Security Council will be

unable to pressure Tehran into curtailing its nuclear program. Iran will use

the U.S. distraction in Iraq to move closer to its objective of becoming a full-fledged

nuclear power, which will in turn strengthen Tehran 's bargaining position on

Iraq and expand its influence in the region.

The United States and

Israel are militarily occupied by Iraq and Hezbollah, respectively. The logic

behind Iran 's strategy is to use this window of opportunity to advance its

nuclear program to the point where a nuclear Iran will have to be accepted as part

of any deal the United States wants on Iraq.

All the pieces might

appear to be falling into place for Iran, but a major shake-up in the Iranian

regime is likely to happen this year, and it could upset Iran 's calculus in

dealing with the United States on Iraq. Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

is terminally ill with cancer and could die this year. His death will send a

shockwave through the Iranian public, which will come to doubt the Iranian

government's ability to navigate the country through this critical period.

There will not, however, be a complete breakdown of the Iranian political

system. There are mechanisms in place to ensure the leadership transition goes

relatively smoothly.

While his health

further deteriorates, Khamenei will likely position former Iranian President

Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani to lead the country. Rafsanjani is believed to be

committed to Khamenei's vision for Iraq and the ascendance of a nuclear-powered

Iran, but he also is known for his pragmatic leanings and ability to negotiate

more easily with the United States. Rumors are also circulating that Iranian

President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's days could also be numbered, and that Khamenei

will make the arrangements this year to remove the firebrand president from his

post. Khamenei's health will likely dictate whether Rafsanjani receives the

position as supreme leader or president before the end of the year.

The United States

will keep a close eye on any potential shake-ups in Tehran to decide how to

proceed in devising a diplomatic strategy. The questions surrounding the

Iranian leadership will ensure that 2007 will largely be a waiting game over

the fate of Iraq.

Israel will make a

big show of the perception that its patience is rapidly wearing thin as Iran 's

nuclear ambitions develop into reality. Israel's focus for this year will be on

pulling itself back together militarily and politically following its defeat in

the 2006 summer war against Hezbollah. Israel is still unlikely to follow

through with threats to launch pre-emptive strikes against Iranian nuclear

facilities this year. Doing so unilaterally would only further compromise the

U.S. position in Iraq once Iran unleashes its militant proxies in the region.

Instead, Israel 's focus will turn toward Hezbollah. Iran made it clear during

the summer war that it will use Hezbollah as a lever in negotiations over Iraq.

Israel badly wishes to eliminate this lever, particularly since Israel has a

pressing need to create conditions under which it could launch a pre-emptive

strike against Iranian nuclear sites. Israel 's strategy to contain Iran 's

nuclear ambitions begins with the crippling of Hezbollah's militant arm. This

rationale likely factored into Israel 's decision to go forth with a full-scale

incursion into Lebanon this past summer, though the results surely defied

Israel 's expectations.

Israel is likely to

revisit its objective of crushing Hezbollah in the summer of 2007, and has

already begun to justify a coming military escalation in Lebanon through public

declarations that Hezbollah and/or Syria will be the one to instigate the conflict.

Who ends up igniting the war is unimportant. The big question for this year

will be whether Israel can develop the capability to root out Hezbollah forces

in their strongholds in the Bekaa Valley. A good deal of restructuring will

have to take place first, beginning with former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud

Barak's return to the political scene.

Israel could move

indirectly to destabilize Hezbollah in Lebanon ahead of a military

confrontation. Hezbollah is currently brimming with confidence, but it also

must be careful to preserve its legitimacy. By provoking sectarian violence in

Lebanon, Israel could pit Hezbollah fighters against fellow Lebanese, which

would wear down Hezbollah's military forces and tarnish its reputation as a

nationalist movement, making the organization more vulnerable to an Israeli

onslaught. The Israeli Mossad could also be engaged in attempts this year to

eliminate elements of Hezbollah's core leadership to further destabilize the

party.

Though Syria will be

busy building up weapons acquisitions from its defense partners in Moscow, the

Syrian regime will be careful to avoid provoking a major military conflict with

Israel. In elections slated for March, Syrian President Bashar al Assad will be

re-elected by a wide margin, and no opposition forces will be strong enough to

challenge the al Assad regime this year. Though Syria will keep the window open

for talks with the United States, it will continue with its agenda to

re-consolidate influence in Lebanon, which involves political intimidation --

frequently in the form of assassinations. The Bush administration is unlikely

to make any major overtures to Syria this coming year, knowing that Damascus

falls well below Tehran in its ability to wield any real influence in Iraq.

Syria will be emboldened through its alliance with Iran and could instigate a

low-level insurgency in the Golan Heights through a shadowy group of militant

actors on the regime's payroll, but will play its cards carefully for fear of

inviting Israeli airstrikes on its own soil.

Lebanon will become

an intense battlefield for Sunni-Shiite influence, mainly played out between

the Saudis on one side and the Syrians and Iranians on the other. The

expiration of Lebanon 's lame-duck President Emile Lahoud's term in office will

come in September and will be preceded by intense political jockeying between

Lebanon 's rival factions over his replacement. In the end, the next president

will likely be a friend to the Syrians. Hezbollah will be able to expand its

influence in the government by forcibly increasing the number of seats that it

and its allies hold in the Lebanese cabinet. With veto power, Hezbollah will be

able to block any major legislation that harms Syrian, Iranian or Hezbollah

interests, including disarmament of Hezbollah's militant arm or any punitive

measures against the Syrian regime for the February 2005 assassination of

former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik al-Hariri. While consolidating its

political power, Hezbollah will intently focus on preparing for a military

confrontation with Israel.

The Sunni Arab

reaction to a rising Iran will intensify in the coming year. Though the Sunni

Arab states are highly dependent on the United States to ensure their national

security, they will make it clear that they are not going to sit idle while the

United States fumbles around in Iraq. The Arab states, particularly Saudi

Arabia and Egypt, will increase pressure on the Americans to act by

strengthening the Sunni insurgency in Iraq and by showcasing plans to develop

civilian nuclear programs to counter Iran.

The sudden departure

of Saudi Ambassador to the United States Prince Turki al-Faisal brought to

light rifts within the Saudi regime over how to deal with Iran 's expansion at

the expense of the U.S. military position in the region. Even though the kingdom

has recently enacted a succession law to oversee the transfer of power,

tensions over the Iraq situation could exacerbate matters. Moreover, Saudi King

Abdullah has sought to bring in people from outside the royal family to fill

key positions within the foreign policy establishment, which will further

complicate these tensions.

Initially, King

Abdullah chose advisers and strategists such as Adel al-Jubeir

and Nawaf Obaid -- a new crop of young, educated Saudis selected for their

expertise -- rather than members of the royal family. Although technocrats long

ago replaced royal figures in the kingdom's oil and economic sector, it seems

the current king plans to gradually replace royals with technocrats in the

foreign policy arena. An example of this was the appointment of al-Jubeir as Riyadh 's ambassador to Washington after Prince Turki

abruptly resigned.

A Cabinet reshuffle

could result in new oil and foreign ministers. While the Oil Ministry will

continue to be managed by a technocrat, the Foreign Ministry portfolio would

likely remain in the hands of the royal family. Despite disagreements within

the top ruling circles on how to deal with an assertive Iran and the rise of

the Shia in the region, it is unlikely that the key players within the House of

Saud will allow these disagreements to lead to instability within the system --

at least not while the sons of Abdul Aziz, the founder of modern Saudi Arabia,

remain firmly in control of the reins of power.

Egypt 's political

system has also entered a period of uncertainty, as President Hosni Mubarak --

given his advanced age and hence deteriorating health -- could either die or

become incapacitated during the course of the next year. Mubarak's absence would

have a destabilizing effect on the country's political system, as questions

would arise over his potential successor's ability to govern as effectively.

Mubarak's probable replacement will be Omar Suleiman, the country's

intelligence chief. The stage will likely be set for Suleiman this year when

Mubarak nominates him as vice president. The uncertainty surrounding Mubarak's

fate has developed into a key issue as Cairo is under domestic and, to a lesser

extent, international pressure to effect political reforms. The government

could conduct a referendum on the constitution and replace the emergency laws

that have been in force since 1981 as a means to sustain its hold on power and

counter the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood, which is the largest opposition group

in the country.

On the

Israeli-Palestinian front, Hamas and Fatah will continue to struggle over how

to create a power-sharing agreement in the government. As long as Hamas can

continue to be bankrolled by the Iranians and the Gulf Arab states, the party

can avoid making any serious concessions to Fatah in reshuffling the Cabinet.

Palestinian National Authority (PNA) President Mahmoud Abbas will not resort to

calling for early elections unless he can be assured that Hamas would be

marginalized in the polls -- an unlikely prospect for the near future. The

stalemate in the Palestinian territories will lead Hamas' leadership to make

gestures with heavy caveats toward recognizing Israel, though Israel will not

take the bait. The Israeli government will work to ensure that Hamas and Fatah

are prevented from coming together in an agreement; while Israel is sorting out

its own issues at home, it will much prefer to have the Palestinians fighting

each other than focusing their attention on attacking Israel. The impasse in

the territories will prevent the Israelis and the Palestinians from engaging in

any serious final-status negotiations this year.

Turkey will have

presidential elections in May and parliamentary elections in November. Barring

a major domestic crisis, the military is unlikely to force early parliamentary

elections to prevent the ruling Islamist-grounded Justice and Development Party

(AKP) from gaining the presidency, though the AKP could see its parliamentary

majority weaken. Turkey 's continued resistance to the European Union's demands

on Cyprus will ensure that EU accession talks will remain stalled this year.

Turkey 's withering EU aspirations will lead the country to turn its attention

more toward its Arab backyard, where Iraq 's worsening situation becomes a

direct concern for Ankara. Turkey will do its best to prevent U.S. forces from

redeploying to northern Iraq. For Turkey, a built-up U.S. military presence in

northern Iraq would be an obstacle to Turkish interests in containing Iraq 's

Kurdish faction. As the United States makes shifts to its Iraq strategy

throughout the year, Turkey will warn Iraq 's Kurdish faction not to make any

bold moves to consolidate its autonomy and lay claim to the oil-rich city of

Kirkuk.

The devolution of al

Qaeda will continue in 2007, as the movement struggles to carry out a major,

successful attack outside its main theaters of operation in Iraq, Afghanistan

and Pakistan. Though the jihadist forces in Iraq were largely eclipsed by Sunni-Shiite

sectarian fighting in Iraq in the latter half of 2006, they are likely to

receive a boost this year as the need for a robust Sunni insurgency grows among

the Sunni Arab states. Iran, at the same time, has an interest in maintaining

the Sunni jihadist component of the insurgency to target U.S. forces. The

Egyptian node of al Qaeda will likely pull off its annual attack in the Sinai

Peninsula, giving the Mubarak government another excuse to crack down on the

country's Islamist opposition. Al Qaeda will try to spread into the Maghreb,

the Levant and deeper into the Persian Gulf this year, though any attempted

attacks are likely to fail.

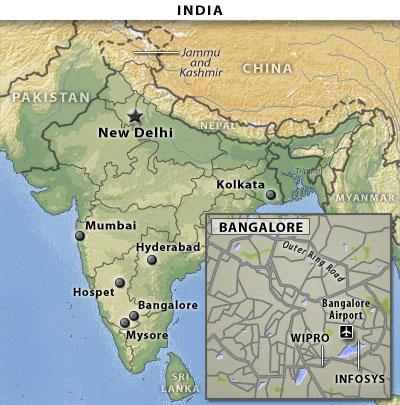

Indian police acting

on an intelligence lead arrested a suspected Kashmiri militant near Jalahalli, a village just north of Bangalore On Jan.5. The

man in question, confessed, to having been tasked with scoping out the

security measures at among others Bangalore airport. And authorities also claimthat the man, named Kota, was acting under the orders

of Pakistan-based militants connected to the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) to plan and carry out attacks.

In South Asia there

will be a focus on the Pakistani political scene, as the country gears up for

general elections slated for Jan. 15, 2008.Musharraf has a comfortable majority

in the sitting parliament to help him win a re-election bid, but his standing

cannot be assured after the general elections are held and a new parliament

comes to power. To consolidate his hold over the government, Musharraf will

bend the rules and schedule a legislative vote ahead of the general election to

get re-elected to another five-year term. Musharraf could even attempt to

bypass this step by calling snap elections in the spring of 2007 if he feels

confident enough in his ability to win. Snap elections or no, the legislative

election results will be rigged as needed to allow Musharraf's parliamentary

allies to hold onto their seats. The opposition forces will then use the

allegations of a rigged election to hold street demonstrations, but are

unlikely to muster enough support to change the election results significantly.

Musharraf will continue with a careful strategy to prevent the PPP, the PML-N

and the MMA from uniting in a potent opposition force, fueling distrust among

the already severely divided parties by hinting at making deals with the

various opposition leaders. Musharraf will also be able to hold onto his

position as military chief this year.

The biggest threat to

Musharraf's election plan is the potential for large-scale U.S. military

activity on Pakistani soil that would undermine the military's confidence in

the general and turn public support against him. To enhance his domestic image,

Musharraf will distance himself from Washington in the coming year and become

even more restrained in cooperating with U.S. forces on the counterterrorism

front.

Pakistan 's relations

with Afghan President Hamid Karzai's government will further deteriorate this

year as the Taliban insurgency strengthens. The Taliban will continue opposing

NATO forces in Afghanistan and launch a spring offensive. NATO is not likely to

have the capacity to surge troop levels and redouble reconstruction efforts.

Nevertheless, Afghanistan will remain -- at least for this year -- a priority

for the alliance. Because the Taliban lacks the strength to take the country

from NATO forces -- and NATO forces are not willing to let things slip that far

-- 2007 in Afghanistan will look much like 2006. Security operations will

continue, and Taliban forces will improve their tactics and build on

operational successes.

More recently on

Jan.5.in India; police acting on an intelligence lead arrested (near Jalahalli, a village just north of Bangalore) a suspected

Kashmiri militant. The man in question as was announced today, confessed, to

having been tasked with scoping out the security measures at among others

Bangalore airport. And authorities also claimthat the

man, named Kota, was acting under the orders of Pakistan-based militants

connected to the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) to plan and

carry out attacks.

Barring a significant

attack by Kashmiri militants on India's IT sector in 2007, no shift in

the Indian political landscape is expected in the coming year; the main

opposition Bharatiya Janata Party is suffering from

internal divisions and is unable to threaten seriously the ruling Congress

party's hold on power. The Congress party's main headache will come from its

allies in the Left Front, who will continue to link up with powerful trade

unions to resist Singh's privatization efforts and labor policies. As a result,

Singh's government will need to turn more toward populist politics in an

attempt to quell domestic unrest.

India and the United

States will cement their landmark civilian nuclear deal this year through a

bilateral treaty; however, Singh will maintain a multilateral foreign policy

agenda to tame the opposition and avoid getting caught in any binding

agreements with the United States that would require it to place a moratorium

on nuclear testing or impose punitive measures against Iran.

India will also keep

a watchful eye on its porous northeastern border, where a political crisis in

Bangladesh spells a likely increase in militant traffic. Whether the Awami

League or BNP emerges victorious means little in the larger strategic view of

Bangladesh; the instability caused by the warring parties is unlikely to wane

regardless of which party is in charge. But the political developments in

Bangladesh will be a cause for concern for India, as the rival political

factions turn increasingly toward radical Islamist parties for coalition

support. The growing Islamist influence in Bangladesh will give rise to radical

groups that will play host to jihadist and Kashmiri militant operatives with an

interest in launching attacks in India.

Further South the

undeclared civil war in Sri Lanka between the Tamil Tiger rebels and Sri Lankan

armed forces has already started to escalate this year in heavy tit-for-tat

fighting as the Sri Lankan army attempts to divide the northern and eastern

Tamil strongholds in the country. Neither the Tamil Tigers nor the Sri Lankan

army has a clear enough advantage to launch a sustained offensive that would

result in a decisive victory however.

For updates

click homepage here