On Oct 7 we presented

a worldwide overview adding, that while the United States suffers under a

time constraint, it has a national plan already in motion to attack the problem

at its source. But while the process in progress could mark the beginning of

the end of the crisis for the United States, the American credit crunch is only

the beginning of the story for the world’s other two major economic pillars:

Europe and Japan.

Then, this morning European economies started putting Sunday's

agreed-upon measures into action.

However, the

underlying reason for Europe’s vulnerability is rooted not in the U.S. subprime

(which became the proximate trigger) but on the importance of banks to the

entire European economy.

At its heart the

financial crisis is that Banks, afraid that other banks could go under at any

time, are refusing to lend money to each other. Banks still willing to lend to

their consumers, whether firms or individuals, are now utterly dependent upon

their own cash reserves. That has drastically reduced the amount of credit in

the system that can reach end users. Which means that a recession, a global

recession, is hardwired into the system until the logjam breaks.

The European

solution, put together by the 15 states that use the euro, to this is to grant

a state guarantee to interbank loans to remove the fear from the banks and

reboot the system. The American solution has two parts. First, use federal

money to empower the Treasury Department to purchase assets of questionable

value (think subprime mortgage securities) from banks so their balance sheets

are friendly and so other banks will be more willing to lend to them on the

interbank. Second, join the interbank network itself via the Fed. The U.S.

Federal Reserve announced on Sunday that they will grant dollar-denominated

loans to any bank affiliated with the Fed or a Fed proxy (which now includes

every bank in Europe or Japan as well) that is interested so long as the bank

can provide collateral. Both methods will introduce large-scale efficiencies,

but that is now deemed better than letting the problems run their course.

Put simply, the

Europeans are guaranteeing the individual transfers of existing banks, whereas

the Americans are simply supplying the market itself by acting as if it were

one of the banks (albeit a very, very large one).

But having a plan and

implementing a plan are two radically different things. In essence both plans

require the government not simply to monitor, but actually to take over the

interbank system — a financial exchange mechanism that has a substantial portion

of the world’s free capital floating within it. This will require a competent

staff of thousands to function effectively, and a competent staff of thousands

cannot be built up in a few days, and perhaps not even in a few weeks. So the

global system is now in the odd position of having identified the road out, but

not having any horses to pull the cart.

The Europeans are

going to have a harder time of this than the Americans, and not simply because

there are thousands of finance professionals in the Wall Street area looking

for jobs. By stepping in as the guarantor, the Europeans will be forced to

evaluate every interbank transaction, matching the lender to the borrower at a

government-approved rate. To simply issue the guarantee and walk away would

allow any bank to lend to anyone risk free, and the size of the corruption that

would stem from that would be far more mind-blowing than the market uncertainty

that would be left behind. This must be managed actively and close up.

The Americans, in

contrast, are actually joining the interbank via the Fed. So rather than having

to approve every interbank transaction, the Fed will only be negotiating with

parties interested in dealing with the Fed itself. Similarly, the Treasury’s bailout

package will only deal with the specific purchases of questionable assets that

the Treasury chooses to explore. Both will sport staggering caseloads, but both

are far less unwieldy than the mammoth task the Europeans face of micromanaging

every deal across the entire interbank market.

Both Europe and the

United States are now in a race against time. Simply having a plan in place is

sure to inject some confidence and loosen up the interbank somewhat, but until

the governments can actually force the market open, global credit will remain

constrained. The severity of this recession will in many ways be determined by

just how fast these programs can get staffed.

And that’s only the

half of the problem that is for today. The other half is for months from now,

when the time comes to get the government out of the business of banking. After

all, outside of crisis times the market is a much better manager than the government.

For the Americans the exit strategy should be somewhat easier: The Fed can

simply put an upper limit on how many dollars it will supply the interbank on a

daily basis and slowly ratchet the number back, allowing normal market forces

to take over gradually.

For the Europeans,

however, it would be more than jarring to simply stop granting guarantees one

clear day and to expect the market to slide back into control as if nothing had

happened. Can you grant a partial guarantee? Can you grant a guarantee to only

certain market participants without being discriminatory? These are questions

the Europeans have now committed themselves to answering in a few months.

In contrast to

the American plan as far it is in place today, the Europeans have two other

reasons for going with its own relatively cumbersome plan. First, the Fed will

need to print a lot of currency to make the American plan work. Authority to print

currency in the eurozone is held by the European Central Bank, not the member

states, so this option isn’t available to the eurozone states at all.

Second, and far more

important in the long run, going into this crisis Europe’s banks were far

weaker than their American counterparts, whose only real problem was subprime

mortgages. Europe’s banking problems are deep, structural and varied. Since a

European bank crisis is the next likely chapter in this financial crisis, the

Europeans are going to need a much firmer grip on their banking sector anyway.

Their plan may be awkward and more expensive, but it is aiming to solve two

problems, not just one.

Thus while in the

United States, the crisis might be contained within the financial and housing

sectors alone, in Europe, the close connections between banks and industry

almost assure a broad and deep spread of the contagion. Unlike the United

States, where the government has spent more than a century battling to break

the links among government, industry and banks, this battle is only rarely

joined in Europe. If anything, such links, one could even say collusion,

between banks and businesses were encouraged from the very beginning of modern

European capitalism.

Since the 19th

century, European financing and investing has been coordinated between banks

and industry, and encouraged by the government, because industrialization was a

modernizing project led by the state that did not spring up spontaneously as it

did in the United States. Bank executives often sat on the boards of the most

important industries, and industrial executives also sat on the boards of the

most important banks, making sure that capital was readily available for steady

growth. This allowed long-term investment into capital-intense industries (such

as automobiles and industrial machinery) without the fear of quick investor

flight should a single quarterly report come back negative.

The most famous

example of this type of cozy link are the ties between Siemens AG and Deutsche

Bank, a relationship which has existed for more than 100 years. An overlapping

and intermingling of interests results from this type of arrangement,

insulating the system from many minor shocks like strikes or changes in

government, but making the system less flexible in the face of major shocks

like serious recessions or credit crises. Therefore, in times of a global

shortage of capital, European corporations are left with few financing

alternatives they are comfortable with. (In contrast, while banks are an

important source of financing in the United States, corporations there depend

much more on the stock market for investment. This forces American firms to compete

ruthlessly for capital and constantly seek greater and greater efficiencies.)

Wholly unrelated to

exposure to American subprime, Europe’s banking vulnerabilities can be broken

down into three categories: the broad credit crunch, European subprime and the

Balkan/Baltic overexposure.

The first issue, the

global credit crunch, exacerbates all inefficiencies and underlying economic

deficiencies that in capital-rich situations would either be smoothed over or

brought to a much softer landing. Think of submerged rocks; many are far enough

below the surface that vessels can simply sail over them. But when the tide

drops, the rocks can become deadly obstacles.

Various European

countries had such inefficiencies long before the U.S. subprime problem

initiated the global credit crunch. Many of these were caused by the post-9/11

global credit expansion in combination with the adoption of the euro. After the

Sept. 11 attacks, many feared the end was nigh. To tackle these sentiments, all

monetary authorities, the European Central Bank (ECB) included, flooded money

into the system. The U.S. Federal Reserve System dropped interest rates to 1

percent, and the ECB dropped them to 2 percent.

The euro’s adoption

granted this low interest rate environment, which normally only a state of

Germany’s strength and heft could sustain, to all of the eurozone. This easy

credit environment echoed by affiliation to most of the smaller and poorer (and

newer) EU members as well. Cheap credit led to a consumer spending boom, which

was stronger in the traditionally credit-poor smaller, poorer, newer economies,

leading not only to a real estate expansion, but also to an overall economic

boom that, even without the subprime issue and the global credit crunch, was

going to burst.

Underneath the global

credit crunch looms the second problem: the European subprime crisis. This

issue is particularly acute in places like Spain and Ireland that have recently

experienced a lending boom propped up by euro’s low interest rates. The adoption

of the euro in Spain, Portugal, Italy and Ireland spread low interest rates

normally reserved for the highly developed, low-inflation economy of Germany to

typically credit-starved countries like Spain and Ireland, granting consumers

there cheap credit for the first time. The subsequent real estate boom, Spain

built more homes in 2006 than Germany, France and the United Kingdom combined,

led to the growth of the banking and construction industry. Banks pushed for

more lending by giving out liberal mortgage terms, in Ireland the

no-down-payment 110 percent mortgage was a popular product, and in Spain credit

checks were often waived, creating a pool of mortgages that might soon become

as unstable as the U.S. subprime pool.

The poorer, smaller

and newer European countries gorged the most on this new credit, and none

gorged more deeply than the Baltic and Balkan countries, leading to the third

problem: Baltic and Balkan overexposure. Growth rates approached 15 percent in

the Baltics, surpassing even East Asian possibilities, but all on the back of

borrowed money. This scorching growth caused double-digit inflation, which will

now make it more difficult for the Baltic states to take out loans to service

their enormous trade imbalances. The only reason that growth rates were less

impressive (or frightening) in the Balkans is because these countries either

came later to EU membership, as with Bulgaria and Romania, or have not yet

joined at all, in the case of Croatia and Serbia, so they did not experience

the full credit-expanding effect of being associated with the European Union.

Fueling the surges were Italian, French, Austrian,

Greek and Scandinavian banks. Limited as they were by their local domestic

markets, they pushed aggressively into their Eastern neighbors. The

Scandinavian banks rushed into the Baltic countries and the Greek and Austrian

banks focused on the Balkans, while the Italian and French also went to Russia.

UniCredit, the Italian behemoth with vast operations across Eastern Europe,

announced Oct. 6 that it was facing a credit crisis, and it is hardly alone.

Fueling the surges were Italian, French, Austrian,

Greek and Scandinavian banks. Limited as they were by their local domestic

markets, they pushed aggressively into their Eastern neighbors. The

Scandinavian banks rushed into the Baltic countries and the Greek and Austrian

banks focused on the Balkans, while the Italian and French also went to Russia.

UniCredit, the Italian behemoth with vast operations across Eastern Europe,

announced Oct. 6 that it was facing a credit crisis, and it is hardly alone.

The “new” European

states have witnessed the greatest expansion in terms of credit, by any

measure, of any countries in the world in the past five years (with the

possible exceptions of oil-booming Qatar and United Arab Emirates). But because

that credit is almost entirely sourced from abroad, the easy credit environment

has now collapsed, and heavy foreign ownership of even the domestic banks means

that those who have the money have their core interests elsewhere. This swathe

of states is now mired in almost Soviet-era credit starvation, while the banks

that once led the charge are having difficulty even maintaining credit lines in

their home markets.

The Challenge of Coordinating a Response

Europe’s inability to

adequately address the challenge goes well beyond the issue that different portions

of Europe face very different banking problems.

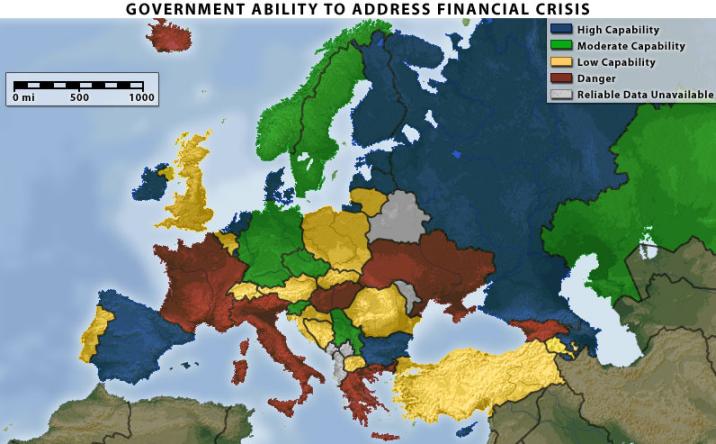

The capacity of

European capitals to deal with the crisis varies greatly, but the core concern

lies in the fact that it is the capitals, not Brussels, that must do the

dealing. When the Maastricht Treaty was signed in 1992, EU member states agreed

to form a common currency, but they refused to surrender control over their

individual financial and banking sectors. European banks therefore are not

regulated at the Continental level, hugely limiting the possibilities of any

sort of coordinated action like the U.S. $700 billion bailout plan.

The Oct. 12-13

announcements are cases in point. While the eurozone members have agreed to

follow general guidelines, any assistance packages must be developed, staffed,

funded and managed by the national authorities, not Brussels or the ECB. This

means that the administrative burden will have to be multiplied 15-fold at

least, as every country undertakes and implements its own bailout/liquidity

injection package.

As the crisis

unfolded, disagreements on the member state level were immediately evident,

with France and Italy initially recommending a Europe-wide bailout proposal

similar to the American plan. France and Italy, both saddled with large and

growing budget deficits and national debts, are the two major states most in

need of such a bailout. But Germany and the United Kingdom, the more fiscally

healthy states that would have been expected to pay for the bulk of the plan,

quickly vetoed the idea.

The Europeans then

decided to go with an EU-wide set of measures that would guide the individual

member states’ liquidity injection packages. At the EU level, the only actual

proposals have been two steps: a broad reduction in interest rates and an increase

in the minimum government-guaranteed bank deposit from 20,000 euros ($27,000)

to 50,000 euros ($68,300). It is worth nothing that many individual European

countries are now guaranteeing all personal deposits to shore up depositor

confidence.

Even in the case of

the interest rate cut, Europe had to dodge EU structures. The ECB’s sole

treaty-dictated basis for guiding interest rate policy is inflation; the treaty

ceiling is 2 percent. Eurozone inflation is already at 3.6 percent, indicating

that rates should not have been reduced. Obviously, circumstances dictated that

they needed to be, but like many states’ decisions to increase deposit

insurance, this move could only be made by ignoring EU law and convention. And

if the ECB can abandon its mandates in times of economic crisis, what stops the

member states from doing the same? The next legalism sure to be widely ignored

will be the prohibitions on excessive deficit spending, which many would call

the fundamental requirement of eurozone membership.

EU treaty details

aside, the issue now will be the ability of the individual states to act. The

stronger a state’s economic fundamentals, the more likely the country in

question will be able to raise money to tackle the situation effectively in

some way, whether by raising taxes or issuing bonds. (Bonds of economies with

good fundamentals in particular are an attractive location for parking one’s

money while stock markets and real estate around the world undergo

corrections.)

The three leading

criteria to consider are the government’s share of the economy, the

government budget deficit and the level of national indebtedness. Combining

these three variables gives a good snapshot of whether a particular country

will be able to raise capital during a credit crunch. Incidentally, European

governments consume the highest percentage of their countries’ resources in the

world, greatly reducing their ability to surge government spending.

Not surprisingly, the

most seriously threatened European states are France, Italy, Greece and

Hungary, each of which is running a serious budget deficit while also being

burdened by high government debt. Three of these four (France, Italy and

Greece) also have very active banks in emerging markets of the Balkans and

Central Europe, home to the European states that are likely to suffer the most

from the credit crisis. These four countries are closely followed by Romania,

Poland, Slovakia, Bosnia, the Netherlands, Portugal and Lithuania.

Further bloating the deficits of many European

countries will be the many bailouts and reserve funds being planned to deal

with the liquidity crisis on an individual country basis. On Oct. 13, Germany

announced a 70 billion euro ($95 billion) bank capitalization plan and up to

400 billion euros ($543 billion) for interbank loan guarantees. On the same

day, France announced slightly smaller figures, a 40 billion euro ($54.3

billion) injection plan for banks and up to 300 billion euros ($407.25 billion)

for interbank loan guarantees. The United Kingdom infused further liquidity

into its banks by propping up Royal Bank of Scotland with 20 billion pounds

($34 billion) and Lloyds and HBOS, which are merging, with 17 billion pounds

($29.2 billion).

Further bloating the deficits of many European

countries will be the many bailouts and reserve funds being planned to deal

with the liquidity crisis on an individual country basis. On Oct. 13, Germany

announced a 70 billion euro ($95 billion) bank capitalization plan and up to

400 billion euros ($543 billion) for interbank loan guarantees. On the same

day, France announced slightly smaller figures, a 40 billion euro ($54.3

billion) injection plan for banks and up to 300 billion euros ($407.25 billion)

for interbank loan guarantees. The United Kingdom infused further liquidity

into its banks by propping up Royal Bank of Scotland with 20 billion pounds

($34 billion) and Lloyds and HBOS, which are merging, with 17 billion pounds

($29.2 billion).

This followed an Oct.

5 announcement by the German government of a (second) bailout proposal for real

estate giant Hypo to the tune of 50 billion euros ($67.9 billion). The

Netherlands and France bailed out Fortis with 17 billion euros ($23.3 billion)

and 14.5 billion euros ($19.8 billion) respectively. Struggling Iceland, where

the country, not just the banking sector, is now technically insolvent,

nationalized its entire banking sector. Nationalization is even sweeping the

usually laissez-faire United Kingdom, which announced that it was seizing

control of mortgage lender Bradford & Bingley on Sept. 29, followed by an

even more dramatic move in which the government announced it would spend 50

billion pounds ($87.8 billion) on rescuing (and thus partially nationalizing)

Abbey, Barclays, HBOS, HSBC, Lloyds TSB, Nationwide Building Society, Royal

Bank of Scotland and Standard Chartered.

Unlike the British

and German bank-specific bailouts, Spain set up a 30 billion euro (about $41

billion) aid package to buy good assets from banks to inject liquidity into the

entire system. The Spanish approach seems to suggest that unlike in the United

Kingdom and Germany, where only a few bad apples needed to be nationalized, the

entire Spanish system might be threatened. This is certainly a possibility in a

country where 70 percent of all bank savings portfolios are in real estate, and

where real estate is dangerously overheated.

Also relevant to

determining the exposure of a particular European state is its dependence on

foreign exports, both in terms of goods and services. By this measure, Germany,

the Czech Republic and Sweden will suffer as their industrial exports slacken

due to a decline in worldwide demand. Extremely high trade imbalances will also

become more difficult to sustain as credit to purchase European exports becomes

more difficult for buyers to procure. Again, particularly at risk are countries

in Central Europe with extremely high current account deficits (in terms of

percentage of GDP). This will be especially true if demand in western EU

countries dulls for Central European exports, further bloating the Central

European countries’ current account deficits, which of course are no longer

easy to finance.

Even assuming that

each bailout plan functions perfectly, and that the U.S. economy pulls through

relatively quickly, Europe is settling in for a protracted banking crisis.

Ultimately, the American problem is limited to the United States’ financial and

housing sectors. Should the United States’ problems spread to other sectors,

the crisis at its core will still remain a credit crunch. In Europe, various

regionalized and interconnected weaknesses are much broader and deeper,

pointing to systemic problems in the banking sector itself. For the United

States, developments the week of Oct. 5 might signal the beginning of the end

of the crisis. But for Europe, this is merely the end of the beginning.

Conclusion: In Europe the liquidity crisis is only the first

step in a broader banking crisis; even in the best case scenario Europe faces

months, not weeks, of recession. In East Asia an American and European

slowdown, even if only for a few weeks in the United States, will depress

demand for Asian exports during the Christmas shopping season, normally the

period of greatest demand. So even in the best case scenario, an inevitable

enervation in the export sector will create gross problems for the Asian economies,

something we will investigate next.

The short list of

countries facing acute problems: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Iceland,

Bulgaria, Sweden, Greece, Italy, Russia, Ukraine, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina,

Venezuela, Pakistan, Vietnam and South Korea.

For updates click

homepage here