By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Following up on a

subject I have covered for a number of years, two

days ago marked three years since a

tribunal found that China's claim of historic rights in the South China Sea was

unlawful. And willing to push back stronger than the Philippines four

heavily armed Vietnamese coastguards have been involved in a week-long

confrontation with Chinese vessels.

To be clear some of

China’s maritime disputes span centuries and started with the Champa Sea or Sea

of Cham a maritime kingdom that flourished before the sixteenth century.

From around the 6th

to the 15th centuries, the South China Sea in fact was known by navigators

throughout Asia as the Champa Seaits various

kingdoms, presided over by regional royal families, also included sizable

portions of eastern Cambodia and Laos.

The oldest artifacts of a distinctly Cham

civilization, brick flooring, sandstone pillars, and pottery found at Tra

Kieu in Quang Nam Province, date to the second century A.D.

The Champa empire was

the chief rival of the Khmer Empire, in Cambodia, and Dai Viet, an early

Vietnamese kingdom to the north. Champa's conflicts with Dai Viet seem to have

started at the end of the tenth century, as the Vietnamese pushed south to the

Cham kingdom of Vijaya (today's Quy Nhon).

Bas

reliefs in a temple at Angkor depict an epic naval battle between the Khmer

and Champa in the 12th century. The Cham navy was unrivaled, but on land the

Cham suffered many costly defeats.

Territorial wrangling

continued until 1471, when Vijaya was finally captured, and by the mid-1600s

the Champa empire had been reduced to its southern kingdom of Panduranga (now

Ninh Thuan and Binh Thuan Provinces, where most of Vietnam's Cham descendants

live today). By then, a Cham diaspora had spread to Cambodia, Hainan, the

Philippines and Malaysia.

In 1832, Emperor Minh

Mang set out to crush the last vestiges of Cham autonomy and stamp out the

culture, burning Cham villages and farmland and destroying ancient temples.

Many Cham fled to Cambodia, where their descendants

number in the hundreds of thousands today.

Whereby the by me

reported on violent demonstrations protests in China against Japan in 2012 can

be traced to the Sino-Japanese War of 1894, while Japan’s defeat in World War

II and Cold War geopolitics added complexity to claims over the Diaoyu/Senkakus

islands. The fight over overlapping exclusive economic zones in the South China

Sea has an equally complex chronology of events steeped in the turmoil of

Southeast Asian history.

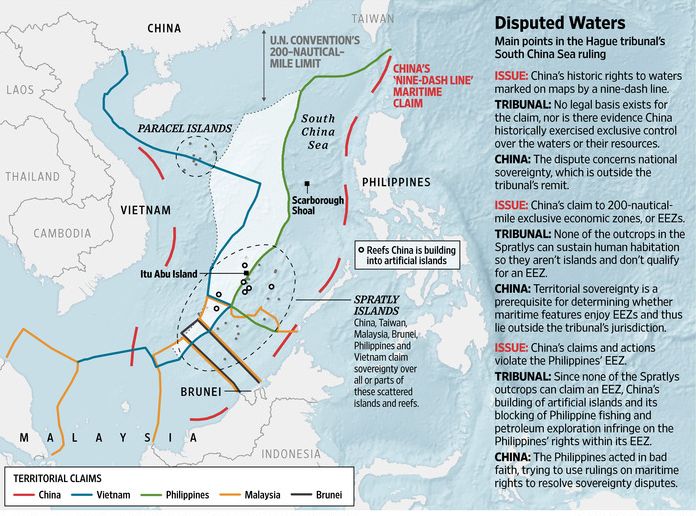

But the key finding

in the South China Sea arbitral award concerned “historic rights” held by China

over ocean space within the nine-dash line. The tribunal found not only that

any “historic rights” China possessed over ocean space were extinguished by the

UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to the extent of incompatibility, but

that there was no historical evidence that China ever exercised such rights of

an exclusive sovereign nature.

Nevertheless, in

recent years, China has undertaken drastic efforts to dredge and reclaim

thousands of square feet in the South China Sea. It has deployed anti-ship and

anti-aircraft missile systems on the Spratly Islands, according to the U.S.

Department of Defense, and constructed military infrastructure on several

artificial islands, such as runways, support buildings, loading piers, and

communications facilities. China’s land development has profound security

implications. The potential to deploy aircraft, missiles, and missile defense

systems to any of its constructed islands vastly boosts China’s ability to

project power, extending its operational range south and east by as much as

1,000 kilometers (620 miles).

China’s highest rate

of island development activity is taking place on the Paracel and Spratly

Island chains. Beijing has reclaimed more than 3,200

acres according to a U.S. Defense Department report.

Experts say that

China’s artificial island building and infrastructure

construction as can be seen below in the case of the

Subi Reef and

underneath the Fiery Cross Reef are

increasing its potential power projection capabilities in the region.

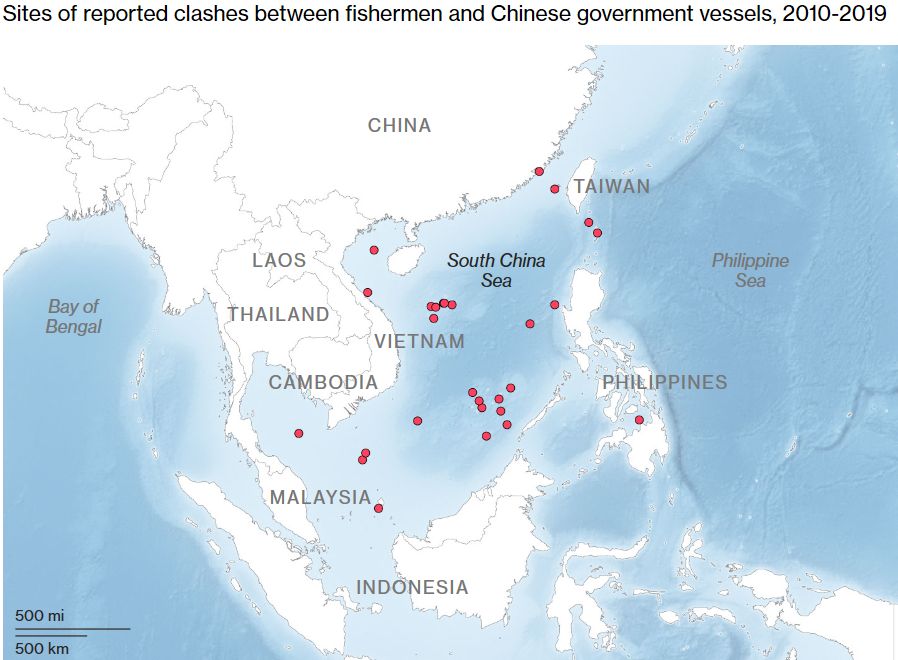

Thousands of vessels,

from fishing boats to coastal patrols and naval ships, ply the East and South

China Sea waters. Increased use of the contested waters by China and its

neighbors heighten the risk that miscalculations by

sea captains or political leaders could trigger an armed conflict, thus crisis

management will be crucial.

Contentious activity

in the South China Sea will also grow as the

U.S. Navy increasingly challenges China's coast guard and maritime militias and

vice versa. Separately, unrest in Hong Kong over an extradition law could

provide an opportunity for the United States to exert targeted trade or

sanctions pressure.

Thus in the near future, tension will continue in the

South China Sea, unless a significant change takes place in the factors that

render China reluctant to initiate reassurance.

For updates click homepage here