The real story of what happened to the

Middle East After the First World War

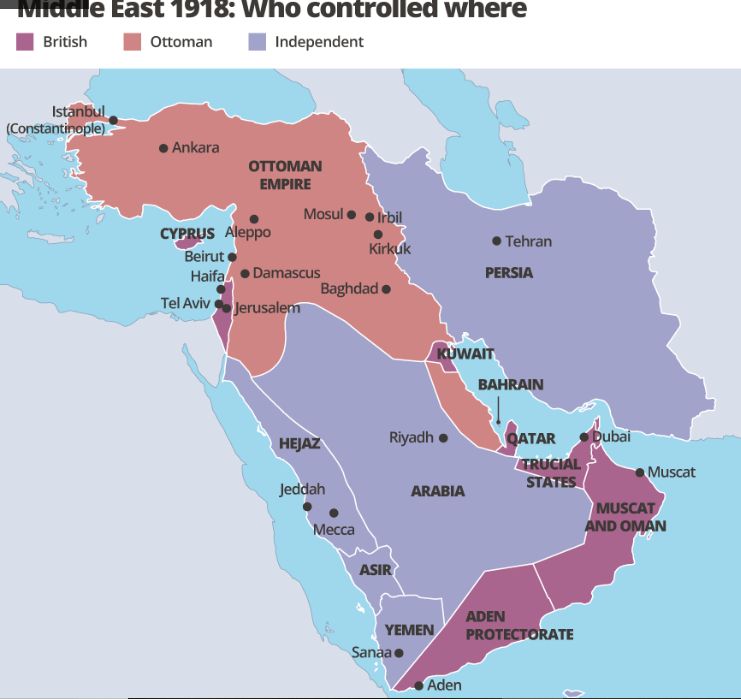

The British who besides

the Ottoman's (with whom they had a good relationship at the time) was the

first major European power to be in that region, and in order to secure their

Suez Canal route to India already in 1881-82 gave up stage-managing events

behind the scenes and simply moved onto the stage by taking over Egypt. The

alleged proximate cause was the attempted coup against the government by Urabi Pasha, a disaffected Arab Egyptian army officer

chafing under the Turkish yoke.

Also in 1914-18

participants in the Middle East had their own reasons for entering the

conflict: the British fought to secure the Suez canal

and the Gulf oilfields; the Turks feared Russian

encroachment and hoped to regain territory lost before the great war; the

Germans sought to destabilize the British empire, the Russians coveted Istanbul

and Anatolia…

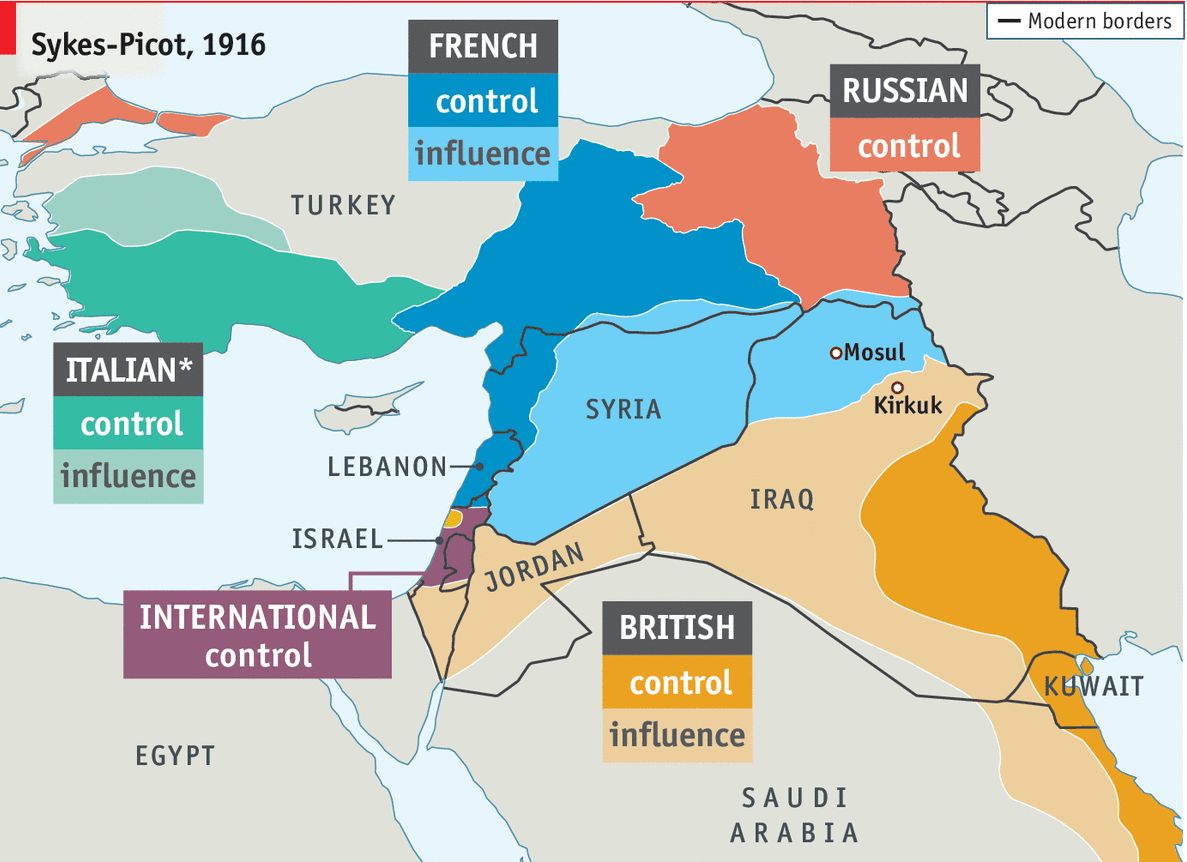

Following the rebellion sparked by the Hussein-McMahon

correspondence; the Sykes-Picot agreement; and

memoranda such as the Balfour Declaration the at

first British (closely followed by the French) in

1918 became very influential in the Middle East.

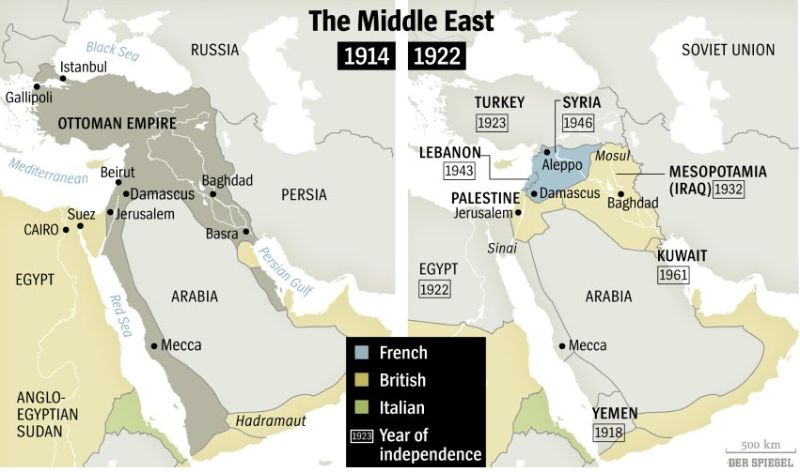

The discussions

between the British and the French who would control what following the break down of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East would reach fever pitch during the Versailles deliberations.

Although its

centennial is to come up next, while even very few people are aware of the

various aspects of the Treaty of Versailles, one should add that there was also the Treaty of Saint-Germain with

Austria on September 10, 1919, the Treaty of Neuilly with Bulgaria on 27

November 1919, the Treaty of Trianon on June 4, 1920 with Hungary, and the

Treaty of Sevres with the Ottoman Empire on August 10, 1920, which subsequently

was superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne made on June 24, 1923 with the new

Republic of Turkey.

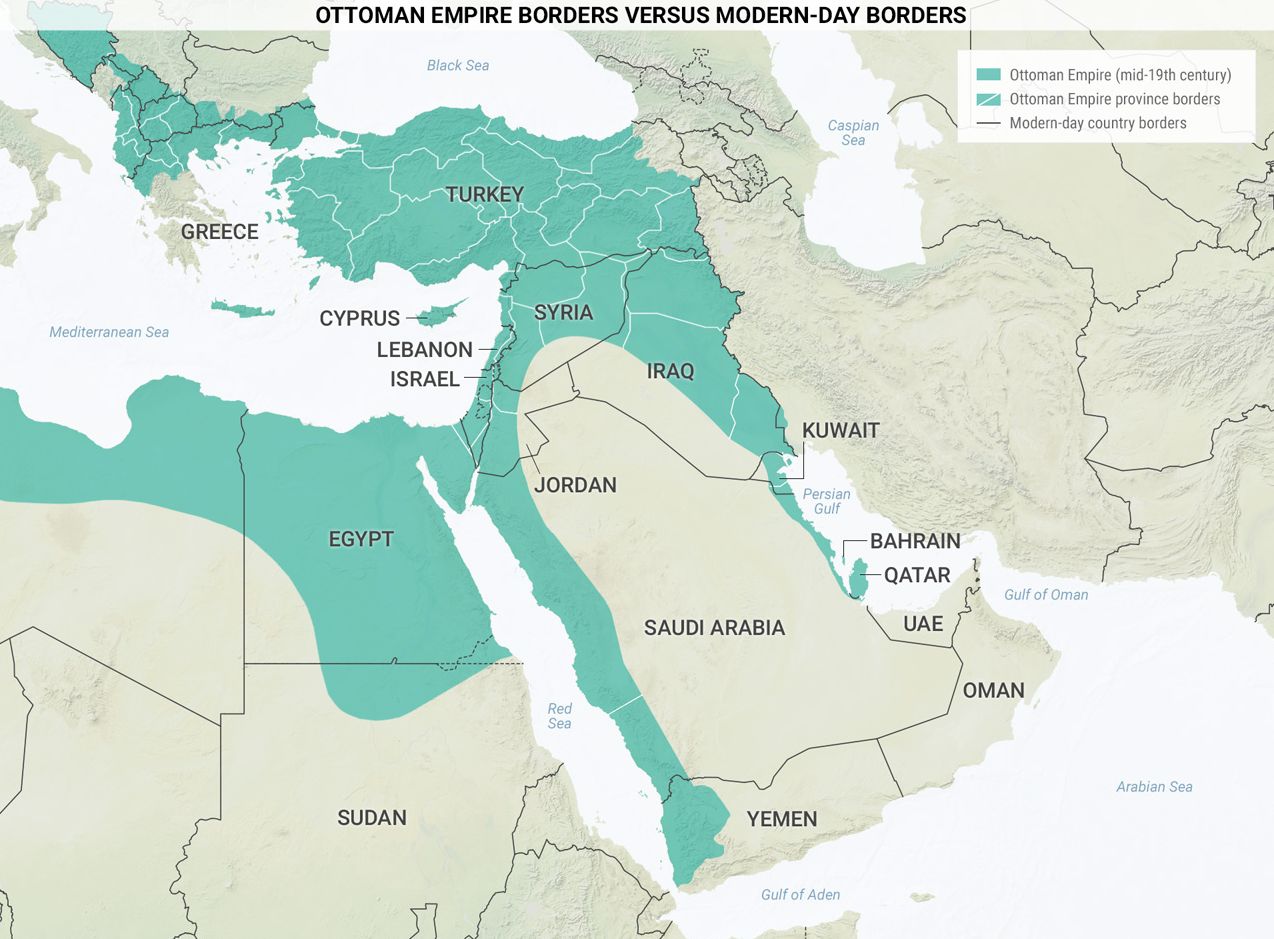

The Treaty of Sevres

covered the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire and

determining the nature of the post-war political entities that took its place.

Following the initial meetings in Paris in the spring and summer of 1919, the

negotiations continued into 1920 with substantive meetings at the

Conference of London (February 12-24) and the San Remo Conference (April

19-26). And it was the San Remo agreement and the mandate policies that were

applied to the newly created Arab countries in Al Mashriq

that replaced the Sykes-Picot agreement. Nothing was left of the Sykes-Picot

agreement except the initial demarcation of Lebanon, Iraq, Transjordan and

Palestine borders.

For many Arabs who

until then simple felt themselves to be inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire, now

broken in pieces, a search for identity would ensue, once a search for survival

had been satiated.

Against the backdrop

of soon to be rising nationalist movements across the Middle East and an

assertive Turkish military and nationalist alliance sweeping away the final

vestiges of Ottoman rule, the wartime allies attempted to maintain political

control by devising and distributing a system of mandates

for administering the region.

At the end of WWI the

history of the making of the modern Middle East thus could be seen as the

exercise of imperial power, skilled at advancing its

interests over those of others.

In 1939, Turkey

seized Syria’s Iskenderun province, in collaboration with the French mandate

authorities.

The British-French

colonization remained in the Al Mashriq countries,

except in the regions of Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and Transjordan, until the

beginning of World War II in 1939. Egypt and Iraq signed treaties with Britain

that practically prevented them from getting their independence until the two

monarchies were overthrown respectively in 1952 and 1958. During the war,

France’s government pledged to grant independence to the countries under its

mandate, amidst the loudening voices of the local political class that called

for independence. Syria and Lebanon gained independence in 1943, two years

before the end of WWII.

The end of the Second

World War instead was greeted in the Middle East as a new beginning. With peace

came the promise of an end to the vast military machine that the British had

built all across the region, a super-imperialism that had turned the Arab states

and Iran (also partially occupied by Russian troops) into mere auxiliaries of

the imperial war effort. Once that had gone, political life might begin again.

Better still, the British had decided (for their own convenience) to lever the

French out of Syria and Lebanon, France's pre-war mandates, and secure their

independence (1946). This was a promising start. They had also encouraged the

formation of the Arab League in 1944-5. The British intended the League to be a

channel of their influence, a way of keeping the Arab states together under a

British umbrella. But it might also serve as a vehicle for Arab cooperation to

exclude or contain the influence of outside powers. The new geopolitical scene

in which Soviet and American power was seen to balance (if not outweigh) that

of Britain made this far less unlikely than it would have been before 1939. To

many young Arabs, there seemed reason to hope that the post-war world would be

a new 'national age'. The false dawn of freedom from Ottoman power after 1918 -

which had led instead to Britain's regional overrule - might at last give way

to the glorious morning of full Arab nationhood. Almost immediately the

barriers piled up. The British rejected the 'logic' of withdrawal: instead they

dug themselves in. (1)

Arguments of strategy

and heavy dependence on oil (still mainly from Iran) made retreat unthinkable.

The strategic vulnerability and economic weakness with which Britain had

entered the peace (London hoped they were temporary) ruled out the surrender of

imperial assets unless (as in India) they had become untenable. In the Middle

East, the British still believed that they had a strong hand. Their position

was founded on their alliance with Egypt, the region's most developed state,

with more than half the population of the Arab Middle East - I9 million out of

some 35 million. (2)

The long-standing

conflict between the Egyptian monarchy and the landlord class gave them

enormous leverage in the country's politics. If more 'persuasion' was needed,

they could send troops into Cairo from their Canal Zone base in a matter of

hours. To improve relations after the strains of war, they now dangled the

promise of a smaller military presence. They assumed that sooner or later the Wafd or the king would want to come to terms, because

Egypt's regional influence, like its internal stability, needed British

support. So, when negotiations stalled, the British stayed put, intending to

wait until things 'calmed down'. They could afford to do so, or so they

thought. For they could also count certain of their historic claim to head the

Arab cause: it was they, after all, who had led the rising after 1916 and

proclaimed an Arab nation. Their long-standing ambition was a great Hashemite

state uniting Syria (lost to the French in 1920) and Palestine with Iraq and

Jordan. Their fiercest enmity, returned with interest, was towards the house of

Saud. (3)

It was the Saudi

monarch who had seized the holy places of Mecca and Medina from their Hashemite

guardian and turned Hashemite Hejaz into a province of what became 'Saudi'

Arabia. Much of the rivalry between Egypt, the Hashemites and the Saudis were

focused on Syria, whose religious and regional conflicts made it a fertile

ground for influence from outside. (4)

This rough

equilibrium of political forces in the post-war Middle East was quickly upset

by the volcanic impact of the Palestine question. The British had planned to

keep their regional imperium by a smooth transition. All the Arab states would

be independent; some would be bound by treaty to Britain; the rest would

acknowledge its de facto primacy as the only great power with real strength on

the ground. It was always going to be difficult to manage this change in the

case of Palestine, ruled directly by Britain under a League of Nations mandate

since the First World War. Reconciling the promise of a Jewish 'national home',

in which Jews could settle, with the rights of the Arabs who were already there

had been hard enough in the 1920's. The flood of refugees from Nazi oppression

in the 1930's made it all but impossible. London's pre-war plan was to appease

the anger of the Palestine Arabs at the growing Jewish migration by fixing a

limit to ensure a permanent Arab majority. With its future settled as an Arab

state, Palestine could be edged towards a form of self-rule. After 1945 this

ingenious solution was soon blown to pieces. The practical difficulty and

political embarrassment of excluding Jewish refugees, diplomatic pressure from

the United States against the attempt to do so, and the scale and ferocity of

the terrorist campaign waged by Jewish settlers destroyed any semblance of

British authority by mid-1948. (5)

The result was the

worst of all colonial worlds: an ungovernable territory whose control was

disputed between two seemingly irreconcilable foes; outside encouragement that

hardened the resolve of both contending parties; and the absence of either the

means or a method to impose any decision. The partition proposed by the United

Nations could not be enforced. The war that followed between the Jews and Arabs

(local Palestinians and the contingents sent by the Arab states) brought a

Jewish victory. The new state of Israel was strong enough to impose a second

and more favorable territorial partition. But it was not strong enough to force

the Arab states to accept this outcome as a permanent condition.

The Arab catastrophe

marked a crucial stage in the end of empire in the Middle East. It galvanized

the sentiment of pan-Arab nationalism and gave it a cause and a grievance. It

was a crushing humiliation for the ruling regimes in the main Arab states, where

post-war inflation and hardship were fostering mass discontent: the violent

demonstrations of the Wathbah (the 'Leap') in Baghdad

in January 1948 had already stopped the renewal of the Anglo-Iraqi treaty. (6)

It provoked bitter

resentment in the ranks of the armies, who blamed their defeat on their

civilian leaders. The impact on Egypt was the greatest of all. The king had

insisted on sending an army, to boost his domestic prestige and assert Egypt's

first place among the Arab states. (7) The shock of defeat was felt all the

more deeply. To make matters worse, he could make little progress towards

evicting the British from their massive Canal Zone, the great visible symbol of

Egypt's subaltern status. Nor indeed could his old political foes, the leaders of the Wafd.

Where diplomacy failed, direct action stepped in. The struggle with the British

became increasingly violent. Strikes, assassination and other acts of terror

exploited British dependence on Egyptian labor and the vulnerable state of

British installations and personnel. Retaliation and revenge spread to Egypt's

main cities. As the sense of order broke down, the king planned a putsch to

purge discontent in the army. Before he could act, the 'Free

Officers' movement seized control of the government in July 1952, and

forced him into exile.

The effects at first seemed

far from radical. The new regime set out to restore order. It crushed the

Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamist movement that enjoyed mass support. It accepted

the loss of Egyptian influence in the upper Nile when British-ruled Sudan was

promised independence as a separate state (the British rejected Cairo's demand

to respect the 'unity of the Nile valley'). Above all, it secured British

agreement to leave the Canal Zone base by conceding a right of return if its

use were needed to repel an outside attack (code for a Soviet invasion) on the

Middle East region. The British had concluded that, with a nuclear deterrent

that they could deliver by air, the base was redundant in its present form as

well as politically costly. (8)

What they probably

hoped was that the new Nasser regime would turn its attention to internal

reform. Egypt, they thought, would exert limited influence in the Arab world.

This was the judgment of the British ambassador in Cairo in July 1954. (9)

Meanwhile, they would

remodel their imperium around a closer alliance with the Hashemite states and a

new military pact. American influence, helpful in making the Suez agreement,

would be thrown on their side. Egypt would be isolated and on its best behavior.

But Nasser's response was not to comply. Instead, his

astonishing revolt against the British 'system' was the central event in the

Middle East's decolonization. (10)

As an Egyptian

nationalist (one of the first acts of the new officers' government was to bring

a statue of Ramses II to Cairo), Nasser had every reason to mistrust the

British and plot their departure from the Middle East as a whole. He was also

influenced by pan-Arab feeling and the Palestine war. He wanted a cleansing

tide of revolutionary politics to smash the old regime of landlords and kings,

left over from the Middle East's colonial era. He also feared that time was

against him. Any ruler in Cairo would have faced much the same dilemma. Sudan was lost. There was high tension with Israel. The

Arab East (the Mashreq) was being closed to Egyptian influence and perhaps even

its trade. Without markets or oil, he faced stagnation at home and growing

social unrest. He would be dangerously dependent on economic aid from the West.

His regime was untried. His critics would multiply. His revolution would fail.

So, as the British assembled their 'Baghdad Pact' (with Turkey, Iraq and - they

hoped - Jordan: Syria was next on the list), Nasser launched a counter-attack.

He embraced pan-Arabism. With Saudi support, he backed the anti-Iraqi faction

in Syrian politics. He encouraged opposition in Jordan to joining the pact.

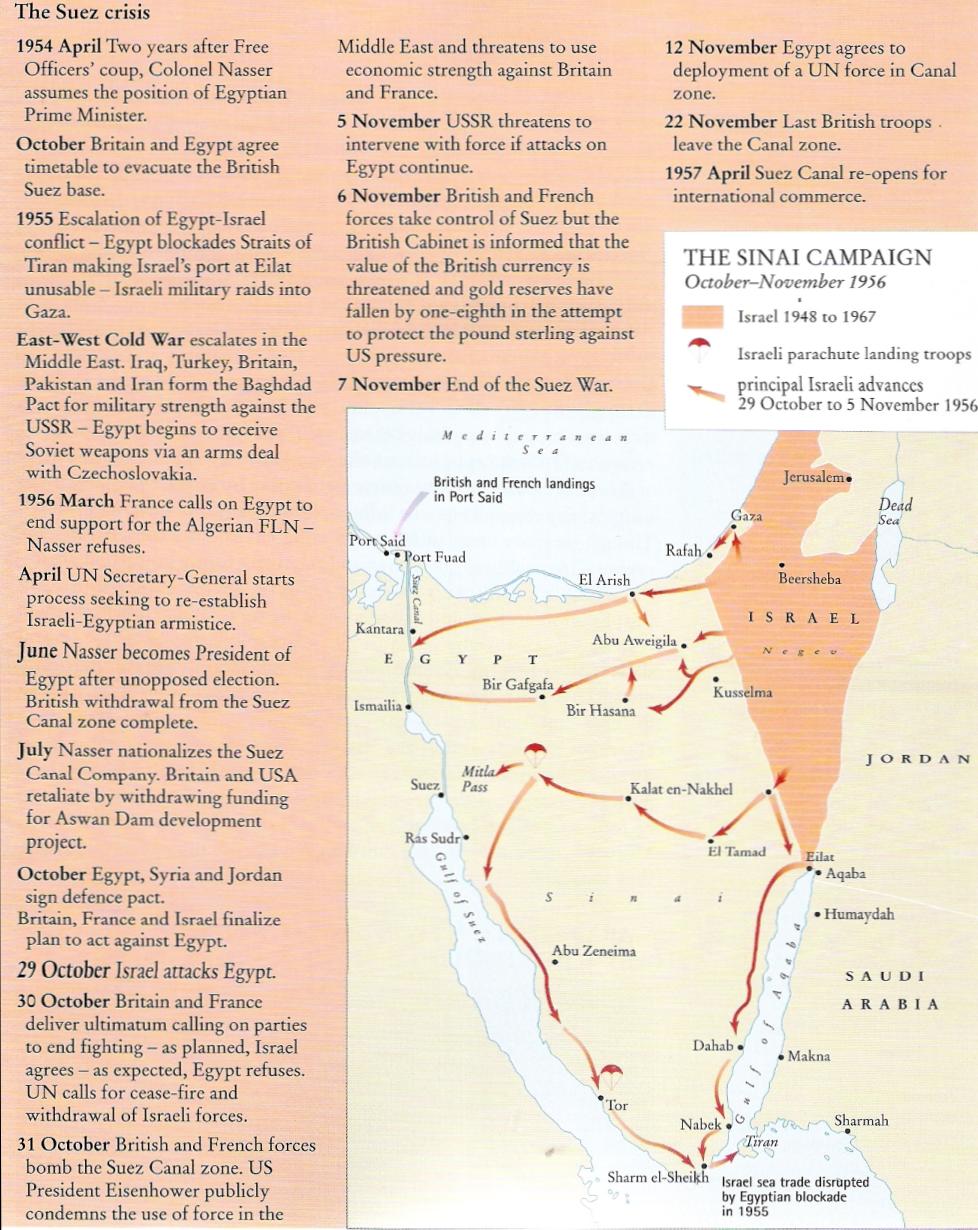

Then in September 1955 came a spectacular coup. Nasser broke free from the

embargo on arms imposed by the West and arranged a supply from the Soviet bloc.

Egypt would now be a

real military power. By early 1956 he had declared an

open political war on Britain's Middle East influence. The rising level of

violence along the borders with Israel played into his hands. With what seemed

amazing ease, he had seized the initiative in regional politics. He had made

Egypt the champion of the pan-Arab cause, and pan-Arab feeling into a dynamic

force. The reaction in London was one of panic and rage. The Suez Crisis in 1956 grew directly out of this

confrontation.

When a loan to pay

for Egypt's Aswan High Dam was stalled in Washington, there was no going back.

Nasser expropriated the Suez Canal, then jointly owned by Britain and France.

It seemed an act of bravado. But perhaps Nasser guessed that the British would

find it hard to defeat him. They no longer had troops in the old Suez base. An

open attack would enrage all Arab opinion. International pressure (through the

United Nations) was unlikely to bring what they really wanted: his political

downfall. Nasser may also have sensed that London's relentless hostility was

not shared fully in Washington. Indeed, the riposte, when it came, revealed

Britain's political weakness. Thinly disguised as an intervention between the

forces of Egypt and Israel (in whose invasion they colluded), the Anglo-French

occupation of the Suez Canal was meant to humiliate Nasser and ensure his

collapse. The key to Nasser's survival was the enormous appeal of his act of

defiance to patriotic Arab opinion. It convinced President Eisenhower that

allowing the British their victory would unite Arab feeling against the West as

a whole, throw open the door to more Soviet influence, and wreck American

interests into the bargain. By a painful irony, the economic fragility that had

helped spur the British into their struggle with Nasser - fear that his

influence would damage their vital sources of oil- now proved decisive. Without

Washington's nod, they faced financial collapse. The British withdrew and ate

humble pie. Nasser kept the canal. So It was not he who fell through the

political trapdoor, but the British prime minister, Sir Anthony Eden. (11)

Suez signaled the end

of British ambition to manage the politics of the whole Arab world. It created

a vacuum of great-power influence. It was the moment to forge a new Middle East

order. Nasser stood forth as an Arab Napoleon. His prestige was matchless: he

was the rais (boss). With its large middle class, its

great cities and seaports, its literature and cinema, its journalists and

teachers, Egypt was the symbol of Arab modernity. Nasser's pan-Arab nationalism

(formally inscribed in Egypt's new constitution) chimed with a phase of sharp

social change in most Middle Eastern states. To the new urban workers, the

growing number of students, the expanding bureaucracy, the young officer class,

it offered a political creed and a cultural programme.

It promised an end to the Palestinian grievance, through the collective effort

of a revitalized nation. Within less than two years of his triumph at Suez,

Nasser drew Syria into a political union, to form the United Arab Republic. The

same year (1958) saw the end of Hashemite rule in Iraq. Nasser still had to

reckon with American power (the United States and Britain intervened jointly to

prevent the overthrow of Jordan and Lebanon by pro-Nasser factions). But

American fears of rising Soviet influence and Nasser's opposition to Communism

allowed a wary rapprochement. It looked indeed as if Nasser had achieved a

stunning double victory. He had displaced the British as the regional power in

favor of a looser, more tolerant American influence. He had made himself and

Egypt the indispensable partners of any great power with Middle East interests.

Pan-Arab solidarity under Egyptian leadership (the new Iraqi regime with its

Communist sympathies had been carefully isolated) opened vistas of hope. It

could set better terms with the outside powers. It could use the oil weapon

(oil production was expanding extremely rapidly in the 1950's). It might even

be able to 'solve' the question of Palestine.

But, as it turned

out, the Middle East's decolonization fell far short of this pan-Arab ideal.

Nasser might have hoped that the oil-rich sheikdoms of the Persian Gulf

(especially Kuwait) would embrace his 'Arab socialism' and throw off their

monarchs. But the British hung on in the Gulf and backed its local rulers

against Nasser's political challenge. Secondly, the pan-Arab feeling on which

Nasser relied faced a powerful foe. In the early post-war years, the new Arab

states seemed artificial creations. The educated Arab elite moved easily

between them. So did their ideas. State structures were weak and could be

easily penetrated by external influence. By 1960 this had begun to change. New

'local' elites began to man the states' apparatus. Every regime acquired its

Mukhabarat, a secret police. The sense of national differences between the Arab

states became clearer and harder: the charismatic politics of Nasser's

pan-Arabism faced an uphill struggle. His union with Syria broke up after three

years. Thirdly, the Israeli state proved much more resilient than might have

been hoped, and its lien on American sympathy showed no sign of failing: if

anything, it was growing steadily stronger by the early 1960s. (12)

Fourthly (and largely

in consequence), the pan-Arabist programme could not

be achieved without help from outside. The search for arms, aid and more

leverage against Israel (and their own local rivalries) drew the Arab states

into the labyrinth of Cold War diplomacy. Lastly, a twist of geological fate

placed the oil wealth of the region in the states least inclined to follow

Cairo's ideological lead: Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Britain's Gulf protectorates.

Nor did oil become (as coal had once been for Britain) the dynamo of social and

industrial change. In fact, Arab prosperity (or the prospect of it) seemed

grossly dependent on an extractive industry over which real control lay in

foreign hands the 'seven (multinational) sisters' who ruled the world of oil. (See

A. Sampson, The Seven Sisters: The Great Oil Companies and the World They Made

(London, 1975).

The second

catastrophe of the 1967 Six Day War, fought between Israel and Egypt, Jordan

and Syria, was a savage reminder that mineral wealth was not the same as power

and that oil dollars did not mean industrial strength. By 1970, the year of

Nasser's premature death,the promise of post-imperial

freedom had become the 'Arab predicament’. (13)

The three largest

states in the Middle East were Egypt, Turkey and Iran (each of which was to

reach a population of 66 million in 2001). With the failure of Nasser's

struggle to make Egypt the center of an Arab revolution, his successor, Anwar

Sadat, turned back (like Mehemet Ali in the 1840's) towards an accommodation

with the West. By the late 1970's Egypt had become the second largest recipient

(after Israel) of American aid.

Turkey, under

Ataturk's shrewd former lieutenant Ismet Inonu, remained

carefully neutral during the Second World War. But the huge forward movement

of Soviet power at the end of the war, and Stalin's open avowal of his designs

on the Straits - 'It was impossible to accept a situation where Turkey has a

hand on Russia's windpipe,' he declared at Yalta - pushed Ankara firmly towards

the Western camp. Under the Truman Doctrine (1947), Turkey was included in the

sphere of American help and protection, however vague at this stage. By 1955 it

had become a full member of NATO. In a way that Kemal Ataturk could hardly have

dreamed of, the pattern of Cold War conflict had opened the door for Turkey's

acceptance as a part of the West, with, a claim to enter the European Union.

Tensions with Greece and over the future of Cyprus (which Turkey invaded and

partitioned in the 1970s) made relations fretful at times. Within Turkey

itself, the key question for much of the half-century after 1945 was how far

Ataturk's grand project of a strong bureaucratic state, with a modern

industrial base and a secular culture, was compatible with representative

democracy (Ataturk's Turkey had been a one-party state) and an open (not

state-dominated) economy.

The case of Iran is

the most intriguing of all. Iran had been jointly occupied by Soviet and

British forces in 1941, partly to block Reza Shah's approaches to Germany,

mainly to secure a free passage for supplies from Britain to an embattled

Russia. Reza Shah abdicated and was sent off into exile. The result was to

unravel his authoritarian state. Resentful notables (the powerful landowning

class), radical movements in the towns (like the Tudeh Party), tribal leaders

(of the Qashgai and Bakhtiari) and ethnic minorities

(Kurds, Arabs and Azerbaijanis) challenged the new young shah's authority and

scrambled for a favor from the occupying powers. At the end of the war, this

instability grew. The Red Army stayed on in Iranian Azerbaijan until 1946. The

effects of wartime inflation ravaged the economy. The supporters of the Shah

struggled with the radicals and notables for control of the Majlis, or

parliament. The government faced increasing resistance from tribal, provincial

and ethnic groups. By 1949, however, the Shah was close to reasserting control,

perhaps because the alternative seemed a further fragmentation of the Iranian

state and a deepening cycle of social unrest.

Before this could

happen, a huge crisis broke out. To restore his position, the shah had been

anxious to swell Iran's revenue from its main source of wealth, the vast

oilfields in the south-west of the country, controlled by the British-owned

Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (today's BP). In July 1949 a so-called 'supplemental

agreement' proposed to increase the royalty that the company paid from 15 to 20

percent, with further increases envisaged. But this agreement ran afoul of two

massive obstructions. The first was the fear among the shah's opponents that

this newfound wealth would seal the revival of his power along pre-war lines.

The second was the much wider hostility across Iranian opinion against

continued foreign control of Iran's key resource and against the influence the

company was believed to exert To make matters worse, while the matter was

debated in the Majlis it became known that Aramco, the Arab-American Oil

Company, had offered a 50 percent share of profits to its host government in

Saud Arabia. As negotiations with Anglo-Iranian ground on, the political

temperature rose and in March 195I the Majlis passed a law to nationalize the

company. A few days later Mohamed Mossadeq, a veteran

antagonist of the Shah and his father, took office as prime minister. (14) The result was a stand-off. British talk of

armed intervention war vetoed in Washington, where London's approach was

regarded as reckless and retrograde. (15)

Instead, the large

British staff was withdrawn from the fields and the Abadan refinery. The major

oil companies, fearing that others might follow the Iranian example, imposed an

inter national boycott on Iranian oil that was very

effective. Mossadeq had seemed on the brink of

achieving a constitutional revolution, but hi support - never very cohesive -

now began to break up. In the Wes he was suspect as a dangerous demagogue,

paving the way for Communist rule. In August 1953 he was overthrown by a military

coup aided and part-funded by American agents with some British support and

replaced by a premier who was loyal to the shah. Under a new oil agreement,

Iran's oil was sold through a cartel of British and American companies. The

shah's oil income rose spectacularly: tenfold between 1954-5 and 1960-61, to

$358 million; and aHurthe fifteen fold by 1973-4. So

did his military and political power. By the early 1960s, he was firmly

established as a major ally of the West whose value as a bulwark against a

Soviet southward advance was offset periodically by the fear that his drive to

be master of the Gulf would set off a conflict with the Arab states of the

region.

1. For a good account

of British policy, W. R. Louis, The British Empire in the Middle East I945-I9F:

Arab Nationalism, the United States, and Postwar Imperialism (Oxford, I984).

2. This estimate is

explained in, W. B. Fisher, The Middle East: A Physical, Social and Regional

Geography (London, I950), p. 249.)

3. Ghada Hashem Talhani, Palestine and Egyptian National Identity (New

York, 1992), p. 9.

4. P. Seale, The

Struggle for Syria: A Study of Post-War Arab Politics 1945-1958 (London, 1966);

A. Rathmell, Secret War in the Middle East: The Covert Struggle for Syria

1949-1961 (London, 1995); P. Seale, 'Syria', in Y. Sadiqh

and A. Shlaim (eds.), The Cold War and the Middle

East (Oxford, 1997); M. Ma'oz, 'Attempts to Create a

Political Community in Syria', in I. Pappe and M. Ma'oz,

Middle East Politics and Ideas: The History from Within (London, 1997).

5. M. J. Cohen,

Palestine and the Great Powers 1945-1948 (Princeton, 1982) is the standard

account.

6. H. Batatu, The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary

Movements of Iraq (Princeton, I978), pp. 470-72, 545-66, 680.

7. Talhani, Palestine, pp. 48-50.

8. For details see R.

McNamara, Britain, Nasser and the Balance of Power in the Middle East 1952-1967

(London, 2003), ch. 3.

9. See James

Jankowski, Nasser's Egypt, Arab Nationalism and the United Arab Republic

(Boulder, Colo., 2002), p. 56.

10. The standard

account is K. Kyle, Suez (London, 1991).

11. For Eden's

political fate, D. Carlton, Anthony Eden (London, I98I). 52. See Rathmell,

Secret War, pp. 160-62; Abdulaziz A. al-Sudairi, A Vision of the Middle East:

An Intellectual Biography of Albert Hourani (London,1981).

12. For the intensification

of America's 'special relationship' with Israel from the late 1950s, see D.

Little, The Making of a Special Relationship: The United States and Israel

1957-1968, International Journal of Middle East Studies 25,4 (1993), pp.

563-85; G. M. Steinberg, Israel and the United States: Can the Special

Relationship Survive the New Strategic Environment?, Middle East Review of

International Affairs 2, 4 (1998).

13. The title of the

influential study by Fouad Ajami (London, 1981).

14. For the onset of

the crisis, E. Abrahamian, Iran between Two Revolutions (Princeton, 1982), ch 5. For Anglo-Iranian, J. Bamberg, The History of the

British Petroleum Company, vol. 2: The Anglo-Iranian Years 1928-1954

(Cambridge, 1994).

15. For the American

view, see for example Rowntree to McGhee, 20 Dec. 1950, in FRUS 1950, vol. 5:

The Near East, South Asia and Africa (Washington, 1978), p. 634. For British

policy, Louis, The British Empire in the Middle East, pp. 632-89.

For

updates click homepage here