Bin Laden, Al-Qaeda,

and Salafi jihadism: Interview with Eric Vandenbroeck

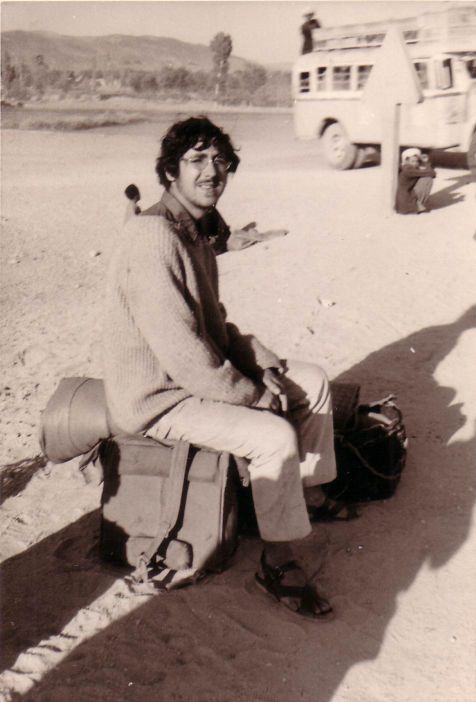

Webmaster of World News Research: You were in

Afghanistan?

Eric Vandenbroeck: Yes, that was before the current

crises, a picture of me in Afghanistan can be seen underneath on this website.

Webmaster of World News Research: What according to you is the current problem

with al-Qaeda and what does the term Salafi means?

Eric Vandenbroeck: At the beginning of the

twentieth century, the term "Salafiyya" was

linked to a transnational movement of Islamic reform whose proponents strove to

reconcile their faith with the Enlightenment and modernity. Toward the end of

the twentieth century, however, the Salafi movement became inexplicably

antithetical to Islamic modernism. Its epicenter moved closer to Saudi Arabia

and the term Salafiyya became virtually synonymous

with Wahhabism.

What happened is that the rise of a transnational and generic Islamic

consciousness, especially after the First World War, facilitated the growth of

religious purism within key Salafi circles. The Salafis who most emphasized

religious unity and conformism across boundaries usually developed puristic

inclinations that proved useful in the second half of the twentieth century.

Due in part to their affinities with the Saudi religious establishment, they

survived the postcolonial transition and kept thriving while the modernist

Salafis eventually disappeared.

Al-Qaeda is not what it is made to be in the Press today. There are

broadly spoken two kinds of people involved, first the ‘intellectual’

activists, men who can justify their attraction to radical Islam in relatively

sophisticated terms. They share many common elements, particularly regarding

their backgrounds, with more moderate political Islamists. This group would

include Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Dr Ayman al-Zawahiri, bin Laden himself, Khalid

Shaikh Mohammed, Omar Saeed Sheikh, Abu Doha, Abu Qutada,

arguably Mohammed Atta and many others.

These people are drawn from the same social groups who were involved in

the earliest Islamist movements of the colonial period. They dominated Islamic

militant leadership cadres in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as filling the ranks

of more moderate organizations. They also share many common elements with

radical political activists on both the left and the right.

In fact, they do not just fit a particular model of Islamic activist

over recent decades; they fit a model of revolutionary cadres over several

centuries. There is no space here to look at the similarities in background

between Egyptian Islamists in the 1970s, Russian anarchists, Bolshevik or

French revolutionaries but it is striking how often it is elements from the

newly educated lower middle classes who are so often at the forefront of

calling for change, even if change is justified by retrospective appeal to a

nostalgically imagined 'just' golden age.

It is not absolute deprivation that causes resentment but, deprivation

following a period of aspiration-raising relative prosperity. In very general

terms, and over the long term, the history of the Middle East and the Islamic

world can be read in these terms.

A lengthy period of international political and cultural dominance has

left a legacy of expectation that is very much at odds with the region's

current subordinate status. The recent economic success of East Asia, for

example, is felt as wrong. It is not fair, right or just. It is humiliating.

This model of expectation, disappointment and perceived injustice works

over a shorter time span too. The expectations of the populations most of the

Islamic activists living in London, or Londonistan as it is called by critics

of the British government's liberal asylum policy, were highly politicized,

educated and relatively moderate.

The number of former convicts or asylum seekers, both marginalized from

mainstream society, among recently recruited Islamic militants is striking.

Significantly, British security officers charged with countering Islamic terror

in the UK have made the monitoring of mosques frequented by young

Afro-Caribbean first or second-generation immigrants a priority.

These two groups are not rigidly defined and individual activists can

show elements of both or neither. Men like bin Laden, al-Zawahiri and Abu Qutada have managed, despite their own backgrounds, to

assume leadership of large numbers of men drawn from the most violent militant

elements. But, despite the flaws inherent in any broad-brushed approach, this

analysis may help us understand why terrorists act as they do.

Modem Islamic terrorists are made, not born. There are various stages in

that process of creation. The route to terrorism starts with a feeling that

something is wrong that needs to be set right. This can be a real problem or

merely a perceived injustice, or indeed both.

The second stage is the feeling that the problem, whether cosmic or

purely personal, cannot be solved without recourse to a mode of action or

activism beyond those provided for by a given society's political or legal

framework.

The third stage changes the individual from being an activist, even a

militant, into a terrorist. It involves the acceptance of an ideology or the

development of a worldview that allows the powerful social barriers that stop

most people from committing acts of violence to be overcome. If recruits are to

be diverted from terrorism it is this process that we need to counter.

The root causes of modern Islamic militancy are the myriad grievances

that lead to the first step on the road to terrorism being taken. Social and

economic problems are critical. Such problems are growing more, not less,

widespread and profound throughout the Islamic world. The economies of states

from Morocco to Indonesia are in an appalling state. Population growth

continues unabated. Unemployment, particularly among critical groups such as

graduates, is still rising fast. Housing is crowded and sanitation basic in

many cities. The gulf between the rich and the poor is increasing.

But these problems alone do not cause terrorism. If individuals have

faith in a political system, a belief that they can change their lives through

activism that is sanctioned by the state or understand and accept the reasons

for their hardships, they are unlikely to turn to militancy. But there is

little reason to be optimistic about the possible development of alternatives

that might divert the angry and resentful from radical Islam in the near

future.

Only in a few small Gulf states has there been any genuine move towards

reform in recent years. One of the reasons for the evolution of a more radical,

debased and violent form of protest is the tendency of governments in the

Middle East to crush moderate movements. Because they are scared of radical

Islam taking power, the regimes block democratic reform. Because there is no

reform, radical Islam grows in support. As national Islamic movements, moderate

or violent, are crushed or fail, anger is channeled into the symbolic realm and

into the international, cosmic, apocalyptic language of bin Laden and his

associates.

This is the biggest threat of all. This is the crucial third stage that

turns an angry and frustrated young man into a terrorist. This is the moment

when an individual begins to conceive of doing something more than shouting

slogans or waving banners. And it is here that the newly dominant, globalised 'al-Qaeda', as a universally transportable,

universally applicable ideology and worldview, is so important. To overcome the

behavioral norms that restrain most balanced citizens in any society from acts

of appalling brutality, particularly against those usually considered

civilians, a powerful legitimizing discourse is needed. The ideologues of

modern 'Jihadi Salafi' Islamic radicalism with their vision of a cosmic

struggle between good and evil, belief and unbelief, the true faith and its

opponents provide one.

The situation now is far worse than when bin Laden began to come to

prominence. The legitimizing discourse, the critical element that converts an

angry young man into a human bomb, is now everywhere. For a number of people,

the 'Jihadi Salafist 'al-Qaeda-ist' worldview

explains everything. It makes sense. There is a battle going on between good

and evil, between right and wrong, between justice and injustice. This is their worldview.

The camps in Afghanistan may be gone but the reasons the volunteer

traveled there persist. Insurgencies and terrorism in Chechnya, Uzbekistan,

Tajikistan, Kashmir, Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Indonesia, Malaysia, the

Philippines and elsewhere continue.

Our societies are open societies. Armoring ourselves may seem useful in

the short term, comforting in the mid-term, but is, in the long term,

impossible. We need to think again about our approach. We need to counter the

twisted vision of the world that is becoming so prevalent. Every time force is

used it reinforces that vision by providing more evidence of a 'clash of

civilizations’ and a 'cosmic struggle.' Every use of force is another small

victory for bin Laden.

Of course the 'war on terror' should have a military component. It is

easy to underestimate the sheer efficacy of military power in achieving

specific immediate goals. Hardened militants cannot be rehabilitated and need

to be made to cease their activities, through legal processes or otherwise. But

if we are to win the battle against terrorism our strategies must be made

broader and more sophisticated. Military power must be only one tool among

many, and a tool that is only rarely, and reluctantly, used.

Currently, military power is the default, the weapon of choice. In fact,

the greatest weapon available in the war on terrorism is the courage, decency,

humor and integrity of the vast proportion of the world's Muslims. It is this

that is restricting the spread of 'al-Qaeda' and its warped worldview, not the

activities of counter-terrorist experts. Without it we are lost. There is

indeed a battle between the West and men like bin Laden. But it is not a battle

for global supremacy. It is a battle for hearts and minds.

Webmaster of World News Research: What is Bin Laden's

relationship with the Taliban?

Eric Vandenbroeck: According to a recent

Frontline article Bin Laden's relationship with the Taliban had never been

easy. His Arab followers tended to look down on the Afghans as unlettered and

uncivil, without the necessary experience, education and intelligence to

understand contemporary politics. In a letter recovered from a computer used by

senior 'al-Qaeda' figures, one complained that the Afghans 'change their ideas

and positions all the time' and 'would do anything for money'.

For their part, Afghans, even Islamic activists, were generally

resentful of the foreigners who had come to their country. Many senior Taliban

figures were angry at the unwanted attention bin Laden was bringing them. Among

the junior ranks of the Taliban, few fighters knew who bin Laden was.

Shortly after the Taliban captured Kabul, bin Laden sent a deputation to

Mullah Omar in Kandahar. It received a cool reception. Several months later, in

early 1997, Mullah Omar asked bin Laden to move from Jalalabad to Kandahar 'for

his own safety'.

Kandahar ironically is where the convoy dropped us and from where we

proceeded with our interpreter to Pakistan. In spite of the looming tribal war

situation there was in fact some light traffic there and a few trucks that were

transporting grapes.

Omar's anger over bin Laden's fatwas however also reveals key

differences between the radical international jihadi Salafism of bin Laden,

with its fusion of Wahhabism and elements of contemporary political Islamism,

and the parochial neo-traditionalism of the Taliban. For the Taliban, only the

Deobandi ulema had the authority to give opinions on religious problems. For

the political Islamists, most ulema are seen as stooges of corrupt and

un-Islamic governments and thus can no longer be considered the guardians and

interpreters of the Islamic tradition. The political Islamists, themselves

largely educated in secular institutions, have adopted a far more flexible

attitude to exactly who has the authority to practice jihad, or interpretative

reasoning.

Maududi, a Pakistani journalist

involved with Jamaat-e-Islami,

viewed the Indian clergy as entirely corrupted by their links to the British Raj,

said, 'whosoever devotes his time and energy to the study of the Qoran and the sunnah and becomes well-versed in Islamic

learning is entitled to speak as an expert in matter pertaining to Islam'.

Hassan al-Turabi, the Sudanese ideologue whose own Islamic credentials could

qualify him as a traditional alim, has said something similar: 'Because all

knowledge is divine and religious, a chemist, an engineer, an economist, or a

jurist are all ulema.'n Al-Turabi is listing the

professional ;coups from which many political Islamists are drawn.

Extreme literalism, and a consequently fierce demand for fatwas, is

typical of many modern Islamic activists. Every group needs its own ulema. Most

set up their own fatwa committee, staffed by senior members of the organization

whose task is to pronounce on the legality or otherwise of any projected

action. Often the committee, its members not usually particularly learned

themselves, refers to a particular authority for definitive answers. For the

al-Gamaa al-lslamivya, that

authority was Sheikh Abdel Omar Rahman. He was able to counter the slew of

fatwas issued against the militants by ulema from the al-Azhar establishment in

Egypt in the 1980s. According to French intelligence, telephone monitoring of

Islamic militant cells in 1999 and 2000 revealed that more calls were made

about minor points of Islamic observance than the terrorist activity the cell

members were supposed to be engaged in. Chechen fighters have requested fatwas

on the legality of telling hostages they were to be released and then killing them,

even after the actual murders.' In March 2000, the Lashkar Jihad group in

Indonesia applied to Sheikh Moqbul al-Wadai'l at the al-Dammaj school

in the Yemen to justify a campaign, backed by the Indonesian military of ethnic

cleansing. 'The Christians have fanned the fires of conflict,' the 70 year¬ old

sheikh told them. 'They have massacred more than 5,000 Muslims. That is why

you, honorable people of one faith, must call all to total jihad and expel all

the enemies of Allah.

In April 1998, the Taliban received a high-level American delegation in

Kabul. In retrospect, this was the highpoint of relations between Washington

and the movement. But Operation 'Infinite Reach' changed everything. As

reported by Anthony H. Cordesman in his book Saudi Arabia Enters the

Twenty-First Century: The Military and International Security Dimensions,Volume 1, 2003, p. 279, three weeks after the

missile strikes, two Saudi Arabian jets landed on the Kandahar airstrip. One

carried Prince Turki, the other, full of commandos, was there to carry bin

Laden back. In a stormy meeting, Mullah Omar reneged on his promise to hand

over the Saudi dissident. Prince Turki asked Omar to remember the substantial

financial assistance Riyadh had given his movement, enraging the Taliban

leader, who accused the prince of doing the Americans' dirty work for them.

Though Turki returned to Saudi Arabia empty handed, Omar was still profoundly

aggrieved with bin Laden too." The ambivalence of the Taliban's position is

amply demonstrated by a news item in their magazine, Nida-ul-Momineen ('The

Call of the Faithful'), published from Karachi, which described yet another

press conference held by bin Laden in September 1998. The headline for the

article was 'bin Laden calls Mullah Mohammed Omar Leader of the Faithful and

says that he will obey him as a religious duty'. The author, Maulvi Obaid-ur-Rahman, repeatedly stressed that 'the guest Mujahid'

denied having any link to the east African bombings.

Webmaster of World News Research: So why did you

mention that al-Qaeda is not what it is made to be in the Press today?

Eric Vandenbroeck: In late November 2001, while

at Tora Bora, bin Laden told his associates to disperse. Money was given to

anyone with a viable plan to launch attacks on Western interests. In fact the

case of one militant who had fled Afghanistan was highlighted in February 2003

when US Secretary of State Colin Powell set out the American case for attacking

Iraq before the United Nations. Abu Musab al-Zargawi,

a Jordanian militant who had been running his own small group in Afghanistan

since the mid-1980s, was forced to leave the country in March 2002. AI-Zargawi had operated independently of bin Laden, running

his own training camp near Herat. It was a small operation and al-Zargawi was not considered a significant player in

Afghanistan at the time. It is likely he had some contact with bin Laden but

never took the bayat and never made any formal

alliance with the Saudi or his close associates. He was just one of the

thousands of activists committed to jihad living and working in Afghanistan

during the 1990s. Wounded in the fighting at Shah-e-Kot, he fled first to Iran,

which expelled him into northern Iraq. From there, according to the Americans,

he sought medical treatment in Baghdad where he remained. Powell called

al-Zarqawi a 'bin Laden associate', revealing either a willful misconception of

the sheer variety of activists and radical groups that were based in

Afghanistan in the late 1990s or genuine ignorance about the real nature of

modern Islamic militancy and, by extension, that of al-Qaeda'.

The FBI and US Treajury estimate that as much

as $100 million has flowed from private sources within Saudi Arabia alone to

'terrorist groups 'in recent years, let alone from other Gulf countries. Huge

sums flow from devout, and not-so-devout, Muslims into Islamic charities from

all over the world. Much of this money is spent on spreading hard-line Wahhabi-style Islam, some is spent on relief for

needy Muslims, some is diverted to fund terrorism.' Since September 11,

donations to radical movements, all over the Islamic world, have substantially

increased.

So on 12 October 2002, three bombs exploded in Bali killing more than

180 people. A group of around a dozen local Indonesian Islamic activists, many

related to each other, were behind the attack.

According to the Indonesian intelligence service, they were directed by Hambali, the veteran militant with links to the 'al-Qaeda

hardcore'. But according to the Indonesian police, and most other analysts, the

Bali group was a radical splinter-group within the nebulous Southeast Asian

network known as Jemaa Islamiya and was largely 'home-grown'.

The group, composed largely of young men who had no previous involvement

in terrorism, were not 'recruited' but came together of their own accord. The

more junior members of the group appear to have been recruited only weeks

before the attack itself. Local police are adamant that no link with 'al-Qaeda'

has been proven. There certainly appears to have been no 'al-Qaeda'

master-bomber, no coordination by any close associate of bin Laden and no

recruitment. The plan appears to have been the bombers' own.

Yet these and a few smaller attacks elsewhere, following the destruction

in Afghanistan of the autumn of 2001, were met with a degree of surprise.

Headlines announced 'the return of al-Qaeda'. But if the 'al-Qaeda hardcore' is recognized for

what it is, one element of the many that comprise contemporary Islamic

militancy, then this surprise and claim,

was not at that point was not warranted.

Instead a swift survey of popular newspapers in the Islamic world (and

beyond) or of Friday sermons in the Middle East's mosques or a few hours spent

in a coffee shop or kebab restaurant in

Damascus, Kabul, Karachi, Cairo, Casablanca or indeed in London or New York

shows clearly that efforts are meeting with

success beyond beyond bin-Laden.

This has two consequences. The first is an ideological convergence among

extant groups, among the 'network of networks'. This can be detected

everywhere. Organizations (and individuals) with no previous interest in

'global jihad' now have vastly broadened perspectives. Where once groups

focused on local concerns, now they look on all that is kufr as their target.

Algerian activists arrested in France in late 2002 were planning to attack the

Russian embassy in Paris in revenge for atrocities committed by Moscow's troops

in Chechnva. In Pakistan, Abu Zubavdah

was captured at a safe house belonging to the Sipa-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP), a

group previously interested only in a local sectarian agenda. The backgrounds

and demands of the men who kidnapped Wall Street reporter Daniel Pearl in

January 2002 are further evidence of the convergence of local groups. The

kidnappers were led by Omar Saeed Sheikh, the British-born Pakistani whose

release had been forced by the HUM hijackers of the Indian plane two years

previously. It is thought that Pearl was actually killed by a Yemeni who had

been fighting in Afghanistan. Other conspirators included members of at least

three different Pakistani groups, none of which had ever shown much previous

interest in international jihad. Palestinian groups are completing their

journey from secular leftist thought to jihadi Salafism. Their struggle, in a

way that has never previously been the case, is being seen, along with Kashmir,

Chechnya and even Iraq, as part of one titanic battle.

Overcoming the fitna, or the factionalism and

parochialism, of militant groups, was one of the main reasons bin Laden set up

'al-Qaeda'. He is finally achieving that aim.

The second result of the new radicalization is that a whole new cadre of

terrorists is being created. The third definition of 'al-Qaeda' outlined in my

introduction was the ideology and the idea of modern radical Islamic militancy,

the resonance of the ideas of bin Laden, al-Zawahiri and their lieutenants

among the broader movement of Islamic activism. It was 'al-Qaeda-ism'. Though

the hardcore is scattered, and the network of networks suffering under the

pressure exerted by local security services, the craving for jihad that sent

tens of thousands of young men to seek training and jihad in Afghanistan is

flourishing. In the post-9/11 environment, the message of bin Laden makes sense

for millions.

So in conclusion I’d say the causes, of terrorism must be addressed, a

careful analysis of the phenomenon that comprises the threat must be

undertaken, moderate Muslim leaders must be engaged, the spread of hard-line strands of Islam rolled back, and an enormous

effort to counter the growing sympathy for the 'al-Qaeda' worldview must be

made. As this is not about one man or one organization.

For updates click homepage

here