By Eric Vandenbroeck

The profound effects of the British Empire’s actions in the Arab World

during the First World War can be seen echoing through the history of the 20th century.

The uprising sparked by the Foreign Office authorizing Sir Henry McMahon to

enter into negotiations with Sherif Hussein, and the debates

surrounding the Sykes–Picot agreement have shaped the Middle East

into forms which would have been unrecognizable to the diplomats of the 19th

century.

The crux the explanation of these events, which now loom so large, is

that Edward Grey and his Foreign Office officials were not very much alive to

the significance of what they were doing because for them Middle Eastern

affairs were simply not that important. This meant that as long as Grey and his

civil servants perceived the advice of various experts not to be inconsistent

with the essence of the Foreign Office’s policy – to uphold the Entente with

France – they were prepared to follow it.

This is why they acted without

much ado upon recommendations by Lord Hardinge, Lord Kitchener, Sir Reginald

Wingate, McMahon, and Sir Mark Sykes, even when these contradicted one another.

This tendency was especially prominent during the first months of the war when

Cairo was alternately instructed to encourage the Arab movement in every way

possible and to refrain from giving any encouragement.

The Ottoman Theater In The

First World War

From the ubiquity of media reference to them, one might suppose that Sir

Mark Sykes and Georges Picot were the only actors of consequence on the Ottoman

theater in the First World War, and Britain and France the only relevant

parties to the disposition of Ottoman territory, reaching agreement on the

subject in (so Google or Wikipedia informs us including in many articles

published the last 48 hours) anno domini 1916.

In fact, virtually none of the Middle East's present-day frontiers were

actually delineated in the document concluded on 16 May 1916 by Mark Sykes and

Francois Georges-Picot (see below). Also for example, Sykes and Georges-Picot

agreed that Palestine would have an international administration. Most of the

area which became Palestine was called the 'brown area' in the agreement, which

was not to be under the control of any particular power, for the ostensibly

high-minded reason that the holy places were there.

In the orthodox narrative Mark Sykes is usually referred to a typical

imperialist and the Sykes–Picot Agreement the epitome of Anglo-French betrayal.

However, if looked at in detail, Sykes emerges as a more complex character and

the Sykes–Picot Agreement as a somewhat less significant instrument of

imperialist double dealing.

It seems that Sykes may have actually believed that his actions had the

best interests of the Arabs at heart: that those conservative and

traditionalist Arabs so prominent in his orientalist conceptualization would be

untroubled by a settlement which only offered them a modicum of national

independence for the foreseeable future.

Certainly, his political alignment before his premature death in January

1919 was closer to those like Gertrude Bell and T.E. Lawrence (‘of arabia’) who thought of themselves as being enlightened

compared with men like Arnold Talbot Wilson and Lieutenant-Colonel Gerard

Leachman. At the same time, it is clear that by the end of the war, the

Sykes–Picot Agreement no longer had the relevance in Anglo-French plans for the

future of the Middle East which it had in 1916. In fact, the ultimate outcome

of the Allies’ deliberations – the mandate system – was in some respects

actually worse for the Arabs than Sykes–Picot, certainly in the case of Syria,

which simply became an outright French colony.

As, among others, Sean McMeekin explained in his book “The Ottoman

Endgame: War, Revolution, and the Making of the Modern Middle East, 1908 –

1923” the partition of the Ottoman Empire was not settled bilaterally by two

British and French diplomats in 1916, but rather at a multinational peace

conference in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1923, following a conflict that had

lasted nearly twelve years going back to the Italian invasion of Ottoman

Tripoli (Libya) in 1911 and the two Balkan Wars of 1912– 13. Neither Sykes nor

Picot played any role worth mentioning at Lausanne, at which the dominant

figure looming over the proceedings was Mustafa Kemal, the Turkish nationalist

whose armies had just defeated Greece and (by extension) Britain in yet another

war lasting from 1919 through 1922. Even in 1916, the year ostensibly defined

for the ages by their secret partition agreement, Sykes and Picot played second

and third fiddle, respectively, to a Russian foreign minister, Sergei Sazonov,

who was one of the driving force behind

the carve-up of the Ottoman Empire.

In fact the 1916 carve-up should be called

the Sazonov-Sykes-Picot agreement. The Russian foreign minister,

Sergei Sazonov, was the prime mover. At the time, the Russian Empire was

victorious on the Eastern Front while Britain had suffered a catastrophic

defeat in Iraq. That all changed in 1917 when the Russian revolution toppled

the Tsar, making many of the provisions of the treaty void.

Henry Laurens, a professor at the prestigious College de France

university, in turn said that the choice of the name

Sykes-Picot was a British invention to diminish the importance of the agreement.

The French were angry because they had discovered that, behind their

backs their British allies had offered the Arabs territory they wanted

themselves. That put their creaky wartime alliance with Britain under added

strain.

To clear the air, Sykes advocated superimposing a deal with the French

upon the British offer to the Arabs. He did not intend the complex compromise

that he then negotiated with Picot to become a blueprint for the region -

indeed he hoped it wouldn't.

The bottom right-hand corner of the map illustrating the agreement,

which both men autographed on May 9, 1916, shortly before their governments

signed off the deal, betrays this with a telling detail. While Georges-Picot

signed in black ink, Sykes only used a pencil.

From a British point of view, Sykes knew that he had failed. His task

had been to protect India by establishing "a belt of English-controlled

country"* across the Middle East, which would have cut across the main

east-west land route running through Aleppo, down the Euphrates, to the Gulf.

Consequent British efforts to resolve these two shortcomings both rewrote the

Sykes-Picot agreement and ensured that it has repercussions today. *As quoted

in Elie Kedourie, Sylvia G. Haim, Palestine and

Israel in the 19th and 20th Centuries, 2013, p 64.

But this plan was thwarted when Picot refused to give him Palestine. The

deal therefore looked flawed even before it dawned on the British government

during 1918 that, with his sweeping line, Sykes had inadvertently conceded

Picot the vast oilfields beneath northern Iraq.

Consequent British efforts to resolve these two shortcomings both

rewrote the Sykes-Picot agreement and ensured that it has repercussions today.

To plug the hole in his cordon sanitaire, Sykes energetically began

wooing the Zionist movement, hoping that the Zionists

would reciprocate by endorsing British rule for Palestine, which they did, with

serious consequences.

But it was not just up to the British that none of the most notorious

post-Ottoman borders, those separating Palestine from (Trans) Jordan and Syria,

or Syria from Iraq, or Iraq from Kuwait, were drawn by Sykes and Picot in 1916.

Even the boundaries they did sketch out that year, such as those that were to

separate the British, French, and Russian zones in Mesopotamia and Persia, were

jettisoned after the war (Mosul in northern Iraq, most famously, was originally

assigned to the French, until the British decided they wanted its oil fields).

After the Russians signed a separate peace with the Germans at Brest-Litovsk in

1918, the entire zone assigned to Russia in 1916 was taken away and thereafter

expunged from historical memory. To replace the departed Russians, the United

States (in a long-forgotten episode of American history) was enjoined to take

up the broadest Ottoman mandates, encompassing much of present-day Turkey, only

for Congress to balk on ratifying the postwar treaties. With the United States

and Communist Russia bowing out of the game, Italy and Greece were invited to

claim their share of the Ottoman carcass, only for both to later sign away

their territorial gains to Mustafa Kemal entirely without reference to the

Sykes-Picot Agreement. Nor was there so much as a mention in the 1916 partition

agreement of the Saudi dynasty, which, following its conquest of the Islamic

holy cities of Mecca and Medina, has ruled formerly Ottoman Arabia since 1924.

Nevertheless Sykes-Picot has become the label for the whole era in which

outside powers imposed their will, drew borders and installed client local

leaderships, playing divide-and-rule with the "natives," and

beggar-my-neighbour with their colonial rivals.

There are also various contrary complaints, like for example “And now

Turkey's enemies are working to create a "new Sykes-Picot" by

dividing up Iraq and Syria, he said, as Kurds in particular seek their own autonomous

regions.”

Or “Sykes-Picot turns 100; the Kurds are not celebrating”.

Not to mention that the two most potent forces explicitly assailing the

Sykes-Picot legacy are at each other's throats: the militants of ISIS, and the

Kurds in the north of both Iraq and Syria.

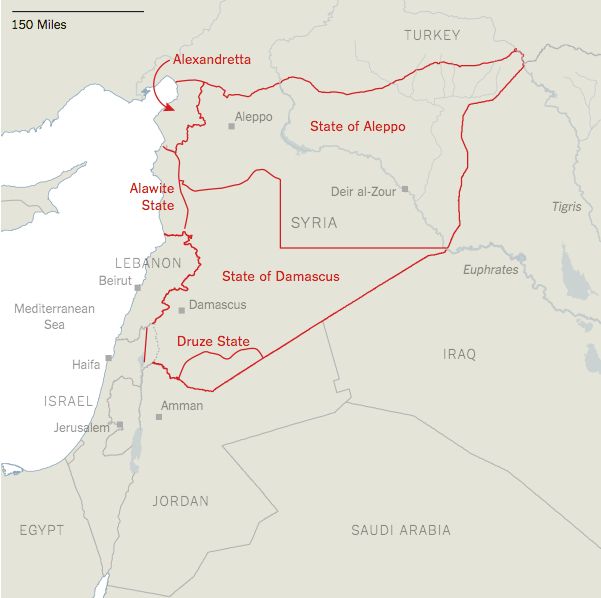

Resented by Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States today the French merged

Aleppo and Damascus states in 1932 under the “State of Syria”, which later

became known as the “Syrian Republic”. They later annexed to it the states of

Jabal al-Druz and the Alawite.

Following the end of WWI, confrontations erupted in the Arabian

Peninsula, whose southern and eastern regions were put under British

protection, between Britain’s two allies - the Emir of Najd Abdul Aziz al-Saud

and King of Hejaz Sharif Hussein. The battles ended when al-Saud seized control

of the regions that fell under the influence of Emir Ali, Sharif Hussein’s

eldest son and heir in Hejaz, in Medina, Yanbu and Jeddah. The latter was

defeated in 1925 and headed to India. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was established

in 1932.

Palestine, meanwhile, had been under the rule of British General Edmund

Allenby since he entered Jerusalem in 1917. Its eastern border with the Emirate

of Transjordan was the border that the “promised national home for the Jews”,

as per the Balfour Declaration, was not allowed to cross. By the end of World

War I, the Sykes-Picot agreement was replaced by the San Remo agreement and the

mandate policies that were applied to the newly created Arab countries in Al Mashriq. Nothing was left of the Sykes-Picot agreement

except the initial demarcation of Lebanon, Iraq, Transjordan and Palestine

borders. In 1939, Turkey seized Syria’s Iskenderun province, in collaboration

with the French mandate authorities.

The British-French colonisation remained in

the Al Mashriq countries, except in the regions of

Yemen, Saudi Arabia and Transjordan, until the beginning of World War II in

1939. Egypt and Iraq signed treaties with Britain that practically prevented

them from getting their independence, until the two monarchies were overthrown

respectively in 1952 and 1958. During the war, France’s government pledged to

grant independence to the countries under its mandate, amidst the loudening

voices of the local political class that called for independence. Syria and

Lebanon gained independence in 1943, two years before the end of WWII.

Thus for Arabs, Sykes-Picot is a symbol of a much deeper grievance

against colonial tradition and is about a whole period during which they

perceive Western powers have played with them and were involved militarily. But

as a Gulf News commentary argues: We’ll never know if Faisal’s map

would have been an authentic substitute to the externally imposed borders that

came in the end.

The French, who opposed his plan, defeated his army in July. But even if

they hadn’t, Faisal’s territorial claims would have put him in direct conflict

with Maronite Christians pushing for independence in what is today Lebanon,

with Jewish settlers who had begun their Zionist project in Palestine, and with

Turkish nationalists who sought to unite Anatolia.

When France took control of what is now Syria, the plan in Paris was to

split up the region into smaller statelets under French control. Today, five

years into Syria’s civil war, a similar division of the country has been

suggested as a more authentic alternative to the supposedly artificial Syrian

state. But when the French tried to divide Syria almost a century ago, the

region’s residents, inspired by ideas of Syrian or Arab unity, pushed by new

nationalist leaders, resisted so strongly that France abandoned the plan.

In 1919, President Woodrow Wilson sent a delegation to devise a better

way to divide the region. Henry King, a theologian, and Charles Crane, an

industrialist, conducted hundreds of interviews in order to prepare a map in

accordance with the ideal of national self-determination.

Was this a missed opportunity to draw the region’s “real” borders?

Doubtful. After careful study, King and Crane realized how difficult the task

was: They split the difference between making Lebanon independent or making it

part of Syria with a proposal for “limited autonomy.” They thought the Kurds

might be best off incorporated into Iraq or even Turkey. And they were certain

that Sunnis and Shiites belonged together in a unified Iraq. In the end, the

French and British ignored the recommendations. If only they had listened,

things might have turned out more or less the same.

We also know that the Arabs of the Middle East had no solid statehood of

their own after the fall of the second Islamic caliphate of the Abbasids in the

13th century. For 750 years, most of today's Middle Eastern Arab world was

ruled by Ottoman and, to a lesser extent, Iranian empires. Thus how could the

new "artificial borders" have been solely responsible for

contemporary Arab states' failures when these countries had no independent

statehood experience for at least seven hundred years?

In fact the Palestinian Gulf News admits that even today, "federalism largely rejected in

modern day Middle East."

Not to mention, the conflicts unfolding in the Middle East today, are

not really about the legitimacy of borders or the validity of places called

Syria, Iraq, or Libya anymore. Instead, the origin of the current struggles

within these countries is over who has the right to rule them. The Syrian

conflict might have began as an uprising against an

unfair and corrupt autocrat, just as Libyans, Egyptians, Tunisians, Yemenis,

and Bahrainis did in 2010 and 2011, yet there is no doubt that it very soon

became a giant three-way proxy war going on between Saudi Arabia, Iran and

Turkey. Those countries are paying the bills of the proxy conflict between

Saudi Arabia/Qatar, Turkey and Iran in any number of countries across the

region.

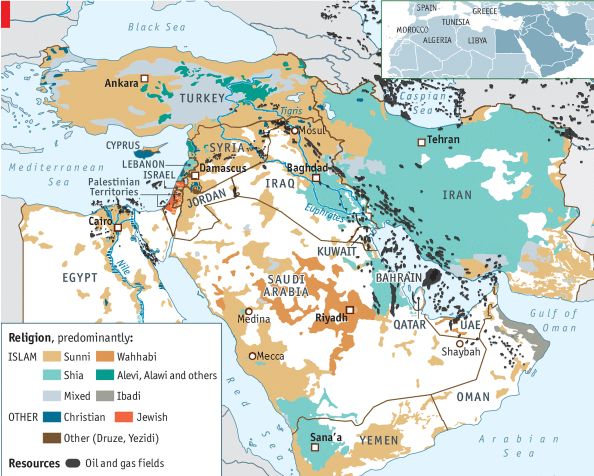

The weaknesses and contradictions of authoritarian regimes are at the

heart of the Middle East’s ongoing tribulations. Even the rampant ethnic and

religious sectarianism is a result of this authoritarianism, which has come to

define the Middle East’s state system far more than the Sykes-Picot agreement

ever did.

The region’s “unnatural” borders did not lead to the Middle East’s

ethnic and religious divisions. The ones to blame are the cynical political

leaders who foster those divisions in hopes of maintaining their rule. In Iraq,

for instance, Saddam Hussein built a patronage system through his ruling Baath

Party that empowered a state governed largely by Sunnis at the expense of

Shiites and Kurds. Bashar al-Assad in Syria, and his father before him, also

ruled by building a network of supporters and affiliates whereby members of his

Alawite sect enjoyed a privileged space in the inner circle. The Wahhabi

worldview of Saudi Arabia’s leaders strongly encourages a sectarian

interpretation of the country’s struggle with Iran for regional hegemony. The

same is true for the ideologies of the various Salafi-jihadi groups battling

for supremacy in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.

Identity politics play a role in the unfolding struggles for control in

the Middle East, but they are not necessarily the root of the region’s

conflicts. Instead, it is the style of politics and government chosen by

successive Middle Eastern leaders that has pitted their own populations against

each other.

In theory, truly inclusive, democratic governments might be able to

govern such heterogeneous countries in a decentralized way without the need for

repression or partition. But in the real world, such ideal governments do not

exist. And attempted political reforms in highly divided societies, far from

encouraging reconciliation, often hasten partition and conflict. In Yugoslavia

in 1990, for instance, the first multi-party elections triggered the state’s

political disintegration.

Does the Middle East Need New

Borders?

In a book published last month "Holy Lands: Reviving Pluralism in the Middle

East" Nicolas Pelham advocates reviving a Ottoman-esque

“milletocracy” in which there are parallel states in

a shared space-said another way, no fixed national borders. Pelham writes,

“From the outset, Ottoman sultans had administered their diverse empire on

sectarian lines, devolving authority to the leaders of their multiple faith

communities, or millets. Patriarchs, chief rabbis, and Muslim clerics headed

semi-autonomous theocracies that applied religious laws. But while the millets

governed their respective co-religionists, they had no power over land. The

empire’s many millets shared the same towns and villages with other millets.

There were no ghettoes or confessional enclaves. Territorially, the powers of

their respective leaders overlapped.”

Think of it as a Middle Eastern Schengen Agreement on steroids. Pelham

sees glimpses of such a plan in present day Baghdad and Najaf. “By decoupling

the rule of the sect from the rule of land,” he writes, “the region’s bloodied

millets might find an exit strategy from secticide

and restore their tarnished universalism.”

The problem with the above proposal however is that someone ultimately

has to rule the land. And the majority sect will never be content with exercising

religious control only over its own people. The first demand is always that the

law of one sect be used to decide legal disputes between sects. Then there will

be demands for blasphemy laws against people in other sects and demands for

punishment of religious converts. As long as there are social/business

interactions between the members of different sects, there will be religious

disputes within the state.

It will remain questionable if new borders (parallel states) will

restore stability. The states themselves must change if there is to be any sort

of peaceful order that can accommodate the demands of the region’s diverse

populations. Yet the prospects for such a transformation are dim.

Even the most ardent critics of the status quo have given no indication

of where the region’s natural borders lie, because there are no natural

borders. The Kurds, for example, aggrieved by a partition of the region that

did not give them their own country, even disagree on whether there should be

one Kurdistan or several Kurdish states.

The Kurdish KRG in Iraq, for all intents and purposes, is an independent

state, with its own national institutions, flag, and army.

But divided among themselves, the Kurds show little solidarity with

their counterparts in Syria and even less with those in Turkey.

The following map shows on the left Kurdish

"Rojava" and on the right the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in

Iraq and Syria.

The Kurds may have thrown off central rule in Iraq and Syria but the

border is still there: despite the Kurds or, perhaps more accurately, because

of them. The Kurds have long talked of reuniting their people in a greater

Kurdistan, but today their population is carved up between not only Syria and

Iraq, but also Turkey and Iran, which have sizable numbers of their own. These

different national populations have discovered over time that what sets them

apart may be more significant than what they have in common: differences in

dialect, tribal affiliation, leadership, ideology, historical experience. And

Kurdish parties on both sides of the Syria-Iraq border are reaffirming these

differences every day with remarkable bureaucratic fastidiousness. What’s more,

the Kurdish parties seem to have internalized the very nation-states they

scorn: in Syria, their leadership and members are almost exclusively Syrian

Kurds; in Iraq, Iraqi Kurds; and in Iran, Iranian Kurds. Only the Kurdish

movement in Turkey, which has pan-Kurdish ambitions, includes Kurds from

neighboring states, though the top leadership is from Turkey (and some only

speak Turkish).

With the central governance from Baghdad that has become a fiction,

another paradigm is a federalized nation, which would give greater autonomy to

Kurds in the far north, Sunni Arabs in the west and Shia Arabs in the south.

Syrian Kurds, for now, deny wanting their own state, but they are

establishing control well beyond Kurdish majority areas in Rojava, in northern

Syria. In March, they declared that their territory was a federal state within

Syria, but they received no support from the international community. This is

unlikely to deter them from strengthening their writ in these areas and seeking

to extend them.

Some Sunnis, including Atheel al-Nujaifi, the

speaker of the Iraqi parliament and the former governor of Nineveh, are arguing

that the Sunni provinces will need special provisions from the Shia-led

government once they are liberated. Nujaifi has even

held up autonomous Kurdistan as an example that the Sunnis should consider

emulating. And even some Shia provinces, such as Basra, which sits on Iraq’s

richest oil fields, are challenging the authority of Baghdad and demanding

autonomy.

The governments of Iraq and Syria naturally reject any change in their

borders, although they can no longer claim to control everything within those

borders. And among the two country’s neighbors, opposition to partition is

equally strong. Russia and the United States also oppose the dismantling of

either: Russia because Syria’s demise would weaken its ally, Syrian President

Bashar al-Assad, and the United States because it is against the partition of

any state. It did not even support the dismantling of the Soviet Union, hoping

that political reform would make it unnecessary.

Instead, the United States, along with the European countries and the

UN, believes that democratic, inclusive governments can bring about peace

without the need for new borders. This belief underpins U.S. efforts to

encourage reform in Iraq and international efforts to negotiate an end to the

conflict in Syria. But the idea has little support in the two countries, except

on the part of liberals whose voices are lost among the clashes of armed

militias and the maneuvering of elites determined to maintain their power and

privileges.

The problem is that a truly inclusive, democratic system would require

eliminating the region’s armed militias, sectarian leaders, and corrupt

elites-in other words, all those who currently hold power. Short of a massive

intervention from the outside, which is not going to happen, nobody can do

that.

Consider Iraq. During the occupation, the United States helped develop-some

would say imposed-a political system based on elections but also on ethnic and

sectarian quotas. But the system broke down after the withdrawal of U.S. troops

and became increasingly Shia-dominated and authoritarian under Prime Minister

Nouri al-Maliki. As a condition of assisting Iraq in the fight against ISIS in

2014, the United States insisted on a new prime minister willing to govern

inclusively, and Haider al-Abadi replaced Maliki. Abadi is now trying to curb

corruption and has proposed a new cabinet of technocrats unaffiliated with

political parties.

But the parties, unsurprisingly, are opposed to being sidelined, and

parliament has not approved the proposed cabinet. The only political figure

other than Abadi who has accepted the idea of a technocratic government is

Muqtada al-Sadr, a fiery, maverick cleric shunned by the major Shia political

parties. Sadr is using the idea to increase his own power by threatening to

unleash demonstrations and street action unless a non-political cabinet is

installed. Reform, in other words, has become a tool in a new intra-Shia

political battle that has nothing to do with democracy or good governance.

The deep political reform that could possibly allow Iraq and Syria to

become stable countries has not begun in either country. Abadi tried to take

some modest steps and failed. Assad did not even try, insisting that all his

country needs is new elections. And progress in the fight against ISIS may only

make the Iraqi and Syrian governments more repressive and provide additional

incentives for those who see new borders as the only solution.

Thus the rights and wrongs of 1916 really don't matter anymore. What

matters a hundred years later is the proxy conflict between Saudi Arabia/Qatar,

Turkey and Iran in any number of countries across the region.

With the possible exception of Iraqi Kurdistan, which was grafted onto

Iraq, there will be nothing “more natural” about that new order than what has

been the status quo for a century.

In the end nurturing governments that are more accountable and

competent, with creative power-sharing between national or federal levels on

one hand and the smaller units of government-in cities, provinces and

regions-on the other is probably the best path to a more peaceful future. Such

an evolution of Arab political culture, away from overly centralized and

authoritarian models to more diffused power structures and greater empowerment

of citizens, would be the wiser way to accommodate the searing divisions within

many of the Middle East’s societies, while still enabling mobility and

multiculturalism when conditions improve. That would be a more difficult and

time-consuming project than castigating two colonial-era mapmakers for their

“lines in the sand”-but it is a more promising one.

For updates

click homepage here