By Eric Vandenbroeck

My 2015 travels to Myitkyina and Kachin State

Back in 2012 I reported about

the Burmese armed forces fight against the

Kachin and China’s collusion with the Myanmar Government.

Unfortunately in spite of the

recent election results not much change is noticeable in Kachin State. Attacks

by the Burmese armed forces are ongoing.

Only weeks ago when people of

a village that came under attack fled

for their lives in a panic, 22 sick,

elderly and disabled persons were

left in their homes without that any aid group was being allowed to move near

the village and help. And this has been going

on for years.

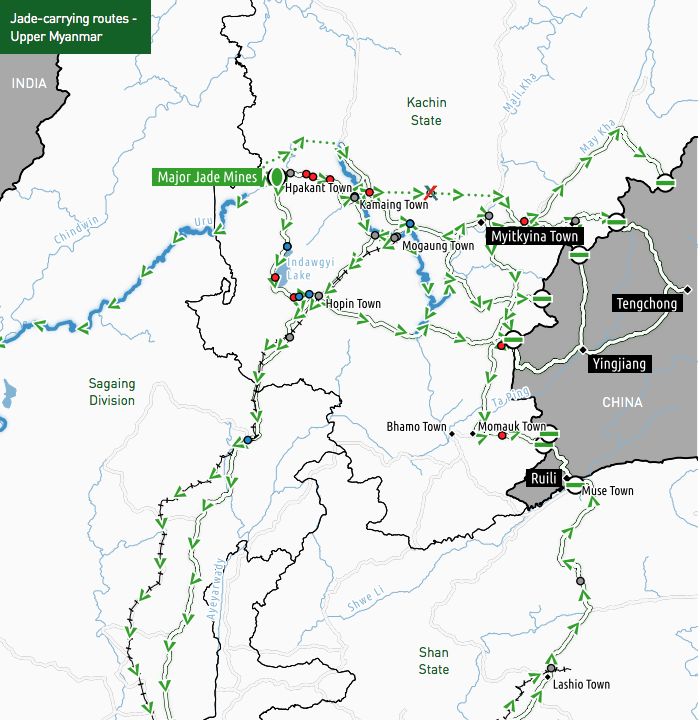

A lot of the current fighting is taking place in the area around

Hpakant, not surprising one of the leading jade-producing zones.

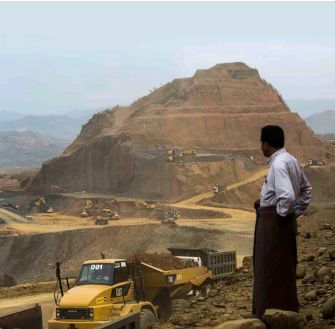

Above a truck stuck on the muddy road to Hpakant, waiting to be dragged

out by elephants. Huge amounts of precious jade have been mined in Hpakant over

decades and yet in Kachin State there are insufficient schools and supply of

electricity, and the roads are in very poor condition.

Discuss jade with a Kachin and they invariably hark back to the old

days, when families could draw on Hpakant’s natural riches to build homes and

make their livelihoods. However, since the military junta parcelled

the jade mines out in the early 1990s, the industry has gone from a small-scale

business in which many local miners could participate to one run by government

approved companies who are often backed up by military force (see below).

From my current position on the outskirts of Myitkyina, the results of

the fighting are noticeable as many

fled to safety here. Upon my arrival, I also found out that next to

Myitkyina airport there is a large military base, and overall, there are more

than 40,000 Burmese soldiers stationed throughout the state. Starting in

October the government has deployed 20 battalions, heavy artillery, and fighter

aircraft.

While my focus here is not tourism, neither is Myitkyina, a hot ticket

for foreigners in general. That probably could have changed if the government

had seen the potential for ecotourism and tiger spotting safaris. At the urging

of American biologist Alan Rabinowitz, known in conservation circles as “the

Indiana Jones of wildlife protection,” the Burmese government designated 13,600

square miles for the world’s largest tiger reserve in the Hukawng

Valley and then promptly set about logging the ancient teak forests and selling

the gold mining rights in much of it to the Yuzana Company, a Burmese business

conglomerate founded by a politically connected tycoon subject to American

investment sanctions who is now a member of Parliament. The Yuzana Company not

only started stripping the tiger habitat of its forests*, but it also seized

(with military backing) hundreds of thousands of acres of Kachin farmland

belonging to the residents of seven villages who had no other means of making a

living. It even tore up roads built by the farmers so they would be forced to

use company roads and pay their tolls.

*In 2012, EIA research revealed that China

was the world’s biggest consumer of Burmese illegal timber, having imported

at least 18.5 million m3 of illegal logs and sawn timber in 2011, worth $3.7

billion, constituting 10 per cent of China’s total wood products imports.

The official Wildlife Conservation Society reports that still some

Tigers supposedly remain in the Hukawng, locals, in

contrast, are reporting that there are no more tigers. In any event, the

numbers are not likely to increase as the Yuzana Company’s gold mining strips

the land bare and releases cyanide contaminating the area soil as well as its

water sources. Leave it to the old school generals of Burma to create the

world’s largest tiger reserve with the fewest tigers. Just as Orwell’s

“Ministry of Plenty” from his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four rations and reduces

the supply of food and other goods while claiming to raise the standard of

living, Myanmar’s Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry

(previously known as the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests) seems to be

hell-bent on selling rather conserving the country’s resources.

Unfortunately, this

kind of land grab is a common occurrence in Myanmar. Sometimes a few farmers

are displaced, and sometimes it’s whole villages. The new claimed democratic

reforms seemed to have little effect on this pursuit. The news website The

Irrawaddy reported in 2014 that a court near Mandalay had sentenced around 350

villagers to prison terms for essentially complaining about having their lands

stolen by the government and given to a private businessman.

Although the hills

around here at the moment seem peaceful to me, the people of Shan State are

well-accustomed to struggle. In the 1960s, Burma's dictator, General Ne Win,

launched a counter-insurgency strategy called the “Four

Cuts,” which were allegedly designed to cut the four main links that rebels

had to food, funds, intelligence, and recruits.

The “Four Cuts” is a

name that connotes precision and strategic thinking, but I guess that calling

it more accurately the “Village Burning Policy” lacks a certain pizazz. The

terrible thing about it is that it has never stopped. Over the years, many in Shan

State have been forcibly relocated, and it is still happening.

Even in 2015, the year of the big presidential election when things are

supposed to be different, villagers in southern Shan State are being forced off

of farmland to make way for a military golf course in the village of Kholam. In an interview with the Democratic Voice of Burma,

one

farmer stated, “I lost all my 10 acres… It includes my farm, garden and

paddy fields. I can’t go to my farm. Soldiers are guarding the area. I have

nowhere to work. Everybody is facing problems, all of us in the district.” that

these farmers initially came to the area when their previous villages were

burned in the “Four Cuts” strategy. First, they have their villages burned and

are forced to flee to another area. Then they are being forced to move again.

Generally speaking, Kachin society includes a variety of different

linguistic groups with overlapping territories and integrated social

structures. These are notably the Rawang, the Lisu, the Zaiwa,

the Lashi / Lachik

and the Lawngwaw and Jinghpaw.

Such definitions carefully distinguish Kachin and Shan (Tai) people though some

Kachin people have defied the Western expectation of lineage-based ethnicity by

culturally becoming Shans.

For the Kachin, the Burman failure to honour Panglong, or what they call the “spirit

of Panglong”, is the original sin of modern Burma.

Officially, the Kachin, should be equal citizens with the Burmans,

enjoying, all the same, rights and opportunities. But the real story has been

and continues to be, very different. Religion (many Kachin are Christian) has

come to be just one of many markers by which the Buddhist Burmans discriminate

against them. They are treated as second-class citizens, or worse, in their

country, and this has been both a cause and a consequence of the bloody civil

wars that most of these peoples have fought with the central Burman authorities

since independence. Thus, the division between the ethnic Burmans, who mainly

occupy the low-lying central plain of the country, and the ethnic groups along

the country’s extensive, winding borders, remains the most serious fault line

in the country. Geography counts for much here. The horseshoe-shaped ethnic

minority region surrounding the Burman core is the distinctive

politico-geographic feature of Burma.

Probably about one-third of the people in the country is non-Burmans. If

the conflicts that this horseshoe fault line has produced are not resolved,

then Burma will never have peace or prosperity, for the first is a prerequisite

for the second. And it is in Kachin State, in the far north of the country,

stretching from the central plains to the foothills of the Himalayas, that the

differences between the ethnic minority groups and the ruling Burmans are at

their most stark. Thus, the real test as to whether the Burmese government

wants to reform, and whether Burma can genuinely look forward to a peaceful,

democratic future will be here, in the lands of the Kachin.

A view repeated by leaders of the Kachin, Karen and Shan, points to the

ongoing rift between the ethnic minority groups, their political parties and

the NLD, is that Aung San Suu Kyi does

not care deeply enough about the ethnic issues, and does not refer to the

Panglong agreement enough. Ultimately, they do not see their interests as being

naturally aligned with the Burman-dominated NLD, and Aung San Suu Kyi had not

done enough to make up for that in her hopes to form a broad, nationwide

coalition to replace the military-dominated governments. It is clear to all

that her immediate concern is with the handover of power to her by the present

government. She wants nothing to be in the way of a smooth transfer.

About 40

miles away from Myitkyina, in the town of Laiza, the Kachin Independence

Organization (henceforth KIO) maintains a stronghold where Kachin

refugees have flocked after surviving encounters with the Government Burmese

Tatmadaw army. I question how long they can defend themselves against

bigger numbers and more advanced weapons.

Asking about the general situation today, a resident of Myitkyina said:

“The generals are thinking they are Burmese kings like in the old days of

history. They think everything belongs to them – the jade, the trees,

everything. Now they look for oil to sell to the Chinese.”

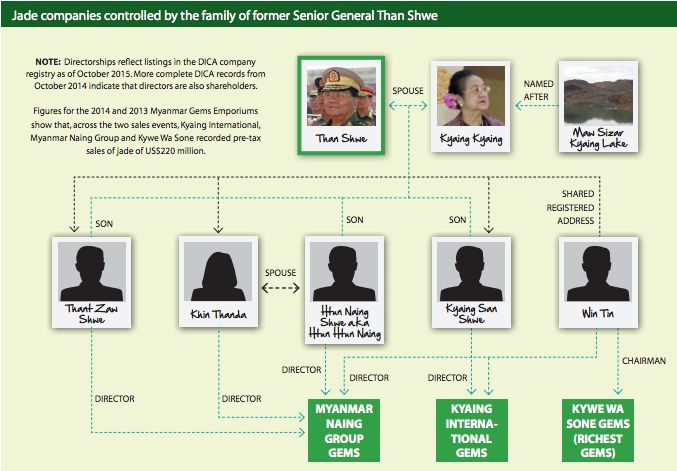

This was confirmed by a recent report that came to the conclusion that

the value of official jade production in 2014 alone was well over the US$12

billion indicated by Chinese import data, and appears likely to have been as

much as US$31 billion. To put it in perspective, this figure equates to 48% of

Myanmar’s official GDP and 46 times government expenditure on health. Clearly,

if openly, fairly and sustainably managed, this industry could transform the

fortunes of the Kachin population and help drive development across Myanmar.

Instead, the people of Kachin State see their livelihoods disappear and their

landscape shattered by the intensifying scramble for their most prized asset.

As seen from an incident a few weeks ago conditions in jade mines are often

fatally dangerous while those who stand in the way of the guns and machines

face land grabs, intimidation, and violence.

The Kachin know all too much about foreign investment, and particularly

the rapacious and destructive side of it. For the Kachin, more than any other

of the ethnic groups in Myanmar can see perfectly well that if they were

allowed a fair share of the fabulous mineral riches that have been extracted by

outsiders from beneath their feet they would now be relatively wealthy, rather

than crushingly poor. This compounds their sense of grievance. For Kachin State

contains many of the country’s biggest and most valuable mines, mostly of jade

and amber, but also of gold. Many of the largest mines are clustered around

Hpakant, said to be home to the highest concentration of bulldozers in the

world – 12,000 or so of them. Here, entire hills and mountains regularly disappear

in the mechanised quest for jade. Such is the demand

for the famously dark-green stone from the Kachin hills that a jade bracelet

sold just over the border in China can fetch up to several thousand dollars.

The Kachin see almost none of this money, which ends up mostly in the pockets

of the Burman generals.

Myanmar’s jade industry may well be the biggest natural resource heist

in modern history. The sums of money involved are almost incomprehensibly high,

and the level of accountability is at rock bottom. As long as the ghosts of the

military junta are allowed to dominate a business worth equivalent to almost

half the country’s GDP, it is difficult to envisage an end to the conflict in

Kachin State. Lessons from other nations afflicted by the resource curse, as

well as Myanmar’s history, suggest that the threats to the country’s wider

political and economic stability are also very real.

Unfortunately so far there is no sign of this after the elections. Or as

one of the leading mine companies commented yesterday: "Until

now, Aung San Suu Kyi hasn't been able to influence the military, so I don't

think an NLD government can either.”

Because of the stepped-up extractions, thousands of ethnic villagers are

being forced off their land. Scavengers, or "handpicked" who in their

thousands scour mountains of loose earth and rubble for nuggets of jade, are

sometimes buried alive, including 114 killed in a

landslide last month.

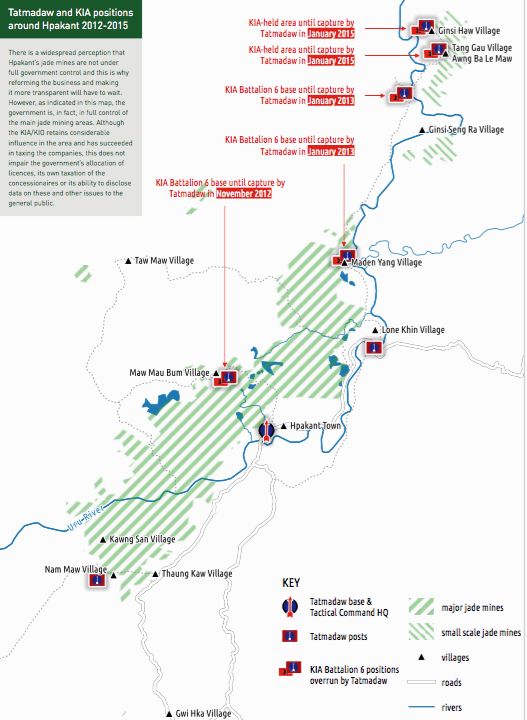

The above map is based on a study done in January 2015. Whereby the

major Burmese armed forces attacks that started early October were intending

completely eradicate all remaining influence of the KIA/KIO in the area for the

generals to take control of the resources.

Below a Burmese Tatmadaw soldier walks through a jade mining site as the

police and military forces come to arrest illegal jade miners and the miners’

families stand and shout in the background. The Tatmadaw systematically extorts

from illegal miners and demands a payment of 20% of the value of each stone

that they find; generating a substantial off-budget revenue stream.

Through its administrative structure, the military government today has

complete control, including of all the schools in the state, tax revenues,

hospitals, the judiciary and, of course, the police.

The Kachin were hoping that the ceasefire

in October would have lead to political talks to

address their numerous grievances. In Laiza, the Kachin established a lively

and authentic Kachin cultural identity, producing school textbooks in Jinghpaw, for instance, and teaching people their history.

But in Kachin State itself, it was more of the same, merely a further

deterioration in the rights, status and culture of the Kachin. But the war only

exacerbated the differences between the Kachin and the Burmans, and this

continued.

Kachin Independence Organization estimates that 15,000 people were displaced because of the project.

Shan State’s 10,000-plus are internally displaced

people (IDPs) are now dispersed between more than ten locations in six

townships.

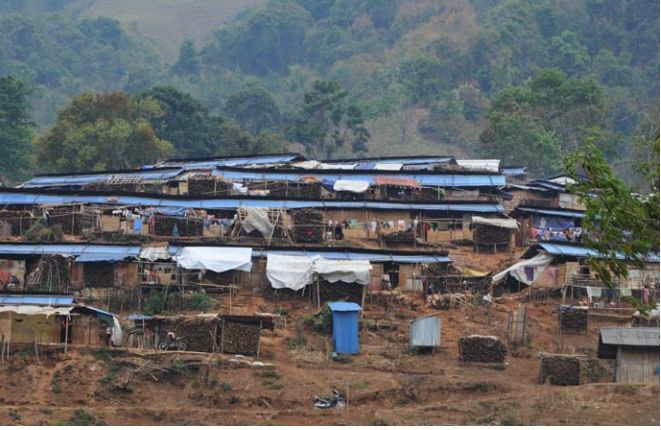

Below and above two camps of

displaced people in Shan State.

Unfortunately, while the election was a step in the right direction,

Myanmar will not be able to enjoy democracy simply because the NLD won the

election. One of the reasons for this is because the election was held under

2008 Constitution, which was adopted from the military’s seven-point roadmap

that enshrines power to the institution.

A major problem for Kachin, as was also the case in many other ethnic

areas of the country, was that of voting

cancellations. The Kachin Democratic Party candidate told one of my

contacts today that ethnic parties in Kachin state the incoming government to

hold by-election soon. “Even if the

by-elections are held, we still won’t be able to form a government, but I want

to know how much understanding and priority the new government will have with

regards to ethnic parties,” he said. In other

areas of the country there are similar situations.

But while the United States and Canada might send election observers to parliamentary

by-elections someone of the diplomatic mission in Yangon told me over the phone

today that the perception is that the Myanmar governement

had not met international standards in this regard.

Sharing similar views as many of the Kachin I spoke to, David Tharckabaw recently mentioned in an interview:

“It would be hard for Ms Suu Kyi and the NLD to

wrest total control away from the military...The military holds three important

ministries – defense, interior and border security. Whatever government is in

power, to be effective in governing the country it needs to amend the

Constitution. That will be difficult. To change the Constitution, the parties

have to get 70% plus one; one from the military. That means the military have

something like veto power again. In reality, they are controlling the power

with the three ministries I mentioned...The national ceasefire will have to be

renegotiated. The Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement was initially demanded by the

ethnic resistant organizations. Of course, the government delayed because they

still want to carry out their strategy of attacking some, making ‘peace’ with

others. The talks have been going on for nearly five years, but with no real

nationwide ceasefire achieve. If the NLD become the government, they have to

lead the peace process. They have to lead the negotiations...Unless we have

real peace, there will be no change. The military and their cronies will

dominate the economy.”

While in reference to Suu Kyi a neutrally worded policy

briefing about the November election today stated: “Unless, however, the

NLD can really reform the structures of national politics, there are already

concerns that the party could go the way of AFPFL governments in the

parliamentary era of the 1950s, concentrating on party politics in the national

capital, failing to end conflict, and continuing the marginalization of

minority peoples.”

Shan Nationalities League for Democracy Chairperson Khun Htun Oo

yesterday criticized Burma’s draft Framework for Political Dialogue (FPD) for a

lack of inclusiveness:

“This

way, it will be like the Two Trees Convention that was held by the military in

the past,” the 72-year-old former political prisoner said, referring to

Burma’s National Convention, a process initiated in 1993 to write a new

national constitution and which ended with the much-criticized 2008

Constitution.

For updates click homepage

here