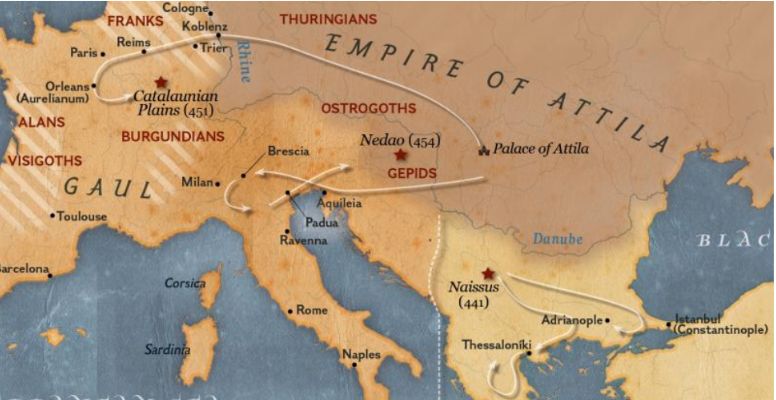

The Huns also called Xiongnu, a nomadic pastoral people who invaded southeastern

Europe c. 370 CE and during the next seven decades built up an enormous empire there

and in central Europe. Appearing from beyond the Volga River some years after

the middle of the 4th century, they first overran the Alani, who occupied the

plains between the Volga and the Don rivers, and then quickly overthrew the

empire of the Ostrogoths between the Don and the Dniester. About 376 they

defeated the Visigoths living in what is now approximately Romania.

The Early Medieval

period (approximately A.D. 400–800) has traditionally been referred to as the

Dark Ages or the Migration Period, yet the objects of personal adornment and

everyday use from this era, from elaborate weapon fittings and ornate buckles

to intricate jewelry, reveal a considerably more complex picture.

406 AD, and the Roman

Empire totters on the edge of the abyss. Already divided into two, the Imperium

is looking dangerously vulnerable to her European rivals. The huge barbarian

tribes of the Vandals and Visigoths sense that their time is upon them. But,

unbeknownst to all these great players, a new power is rising in the East. A

strange nation of primitive horse-warriors has been striking terror on border

peoples for fifty years. But few realize what is about to happen.

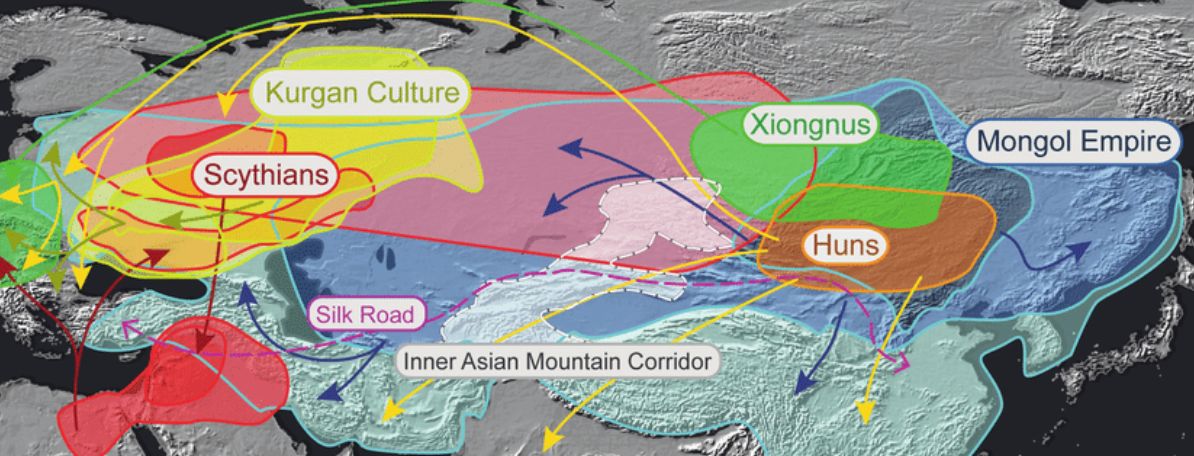

In the fourth century

AD, an offshoot of the Xiongnu (Hun-nu) nation moved

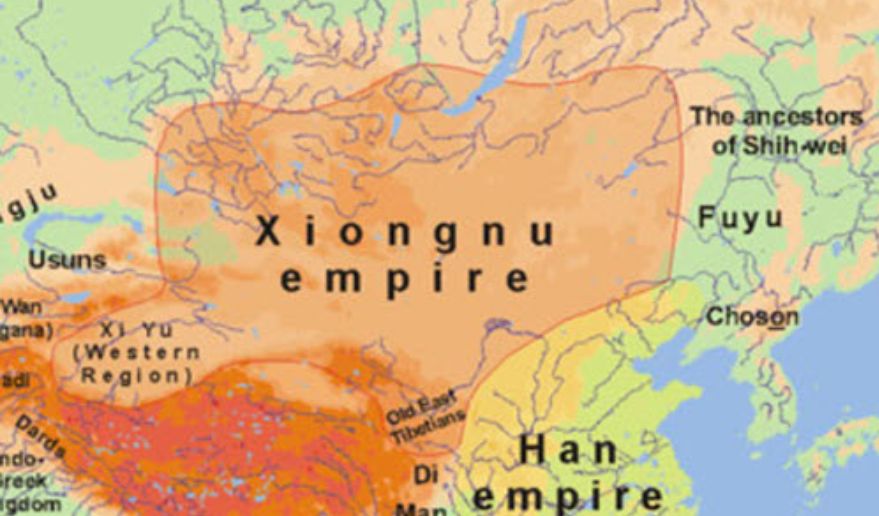

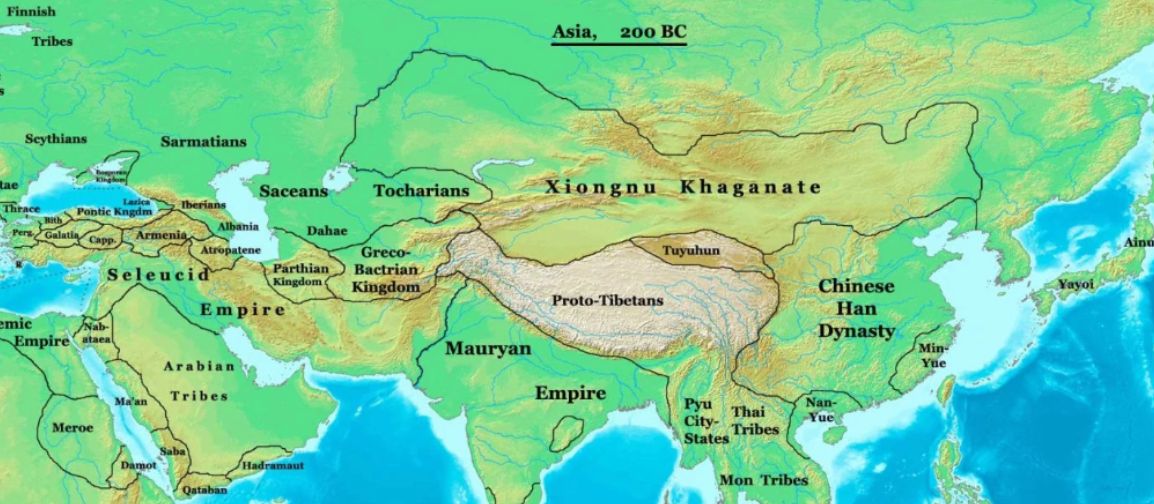

west onto the Pontic-Caspian Steppe. The Xiongnu (Chinese: 匈奴, Hsiung-nu in Wade-Giles romanization) were a tribal

confederation of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources,

inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st

century AD.

At the end of the 3rd

century BCE formed a great tribal league that was able to dominate much of

Central Asia for more than 500 years. China’s wars against the Xiongnu, who were a constant threat to the country’s

northern frontier throughout this period, led to the Chinese exploration and

conquest of much of Central Asia.

It is this Xiongnu faction, that is known to the Romans as the Huns,

defeated the Alani and conquered the populous Gothic realms in Eastern Europe.

In the process, they caused a significant refugee movement into Europe, which

destabilized the Roman Empire. Over the following century, the Huns launched

devastating attacks on Roman territory that destroyed frontier defenses and

eventually caused the downfall of the Western Roman Empire (AD 476).

This westward movement of Xiongnu people

occurred in a period of Chinese history known as the Sixteen Kingdom Era

(AD 304–439).

As the Huns

emerged from somewhere north of the Caspian to approach the Black Sea in the

mid-fourth century, they were, in Roman eyes, at the very limit of the known

world. But with spotlights borrowed from anthropologists and archaeologists it

is possible to highlight a few of their defining traits. As visitors to the

Huns found later, they had beards, grew crops, were perfectly capable of

building houses. Their bulkiest possessions were huge cooking-pots, cumbersome

bell-shaped things with hefty handles, up to a metre

in height and weighing 16-18 kilos: cauldrons big enough to boil up clan-sized

casseroles, dozens of them have been found mostly in E.Europe

although we know that the Huns invaded all the way into W.Germany. To any good metal-caster, these would seem

amateurish, not a patch on Chinese bronze pots or those made by the Xiongnu.

But these were people

on the move, which makes the cauldrons interesting. Hun metalworkers had the

tools to melt copper (it takes a furnace to create a temperature of 1,000°C)

and some large, heavy stone moulds. The cauldrons

alone - leaving aside the decorated saddles and horse harnesses - disprove the

idea that these were just primitive herders who knew nothing but fighting and

ate raw meat. It takes a large, well organized group and surplus food to

support and transport metalworkers, the tools of their trade and their

products. I once participated at an archeological dig in Unterlengenhardt

(S.Germany) one of the places in W.Germany

where evidence of a ‘Hun presence’ was found.

What the Huns

believed, exactly, and how they worshipped are entirely unknown, but there can

be no doubt that they had religious beliefs, and were animists. Tenger turns up all across Asia, from the Tengri desert of

Inner Mongolia to an eighth-century bas-relief in eastern Bulgaria. In Mongol,

as in many other languages, tenger means simply `sky'

in its mundane as well as its divine aspect. The Mongols' Blue Sky - Khokh Tenger - is a deity as well

as a nice day. And it is at least evidenced that like the Romans, the Huns

practiced forms of divination.

As an example it

should further be noted that the idea of one god is supposed to have evolved

from polytheism as a higher form of religion. But for example when American

missionaries when they arrived in the Ecuadorean rainforests reported about the

primitive Waengongi, that they had a cosmology, with an afterlife - a heaven

where people swung in hammocks and hunted for ever, a limbo for those who

returned to this world in animal form, and an underworld of the `mouthless

ones' - and spirits both good and evil, and a myth of creation, overseen by the

creator.

What interested me in

the context of a history of Globalizations, however is what set the Huns in

motion? Why would a small tribe in the depths of Asia suddenly explode onto the

world stage?

Once, it was

fashionable to ascribe large migrations and nomadic assaults to climate change

and the pressure of population, as if the `heartland' were in fact a vast heart

beating to some hidden ecological rhythm, pumping out an arterial flow of

peoples westwards. But climate alone is not a sufficient explanation, for to a

lesser tribe it might have been as fatal as a drought to impoverished

Ethiopians.

Yet the history

of China, is a series of dynastic heartbeats

that has continued, with each beat lasting anything from decades to centuries,

for over 2,000 years. The emergence and collapse of dynasties over such a

period is unique in some four millennia, and many historians have spent their

lives trying to spot an underlying pattern in this remarkable sequence. If

there is one, it seems to have something to do with the idea of unified rule,

in pursuit of which dynasties have followed each other, their life-histories

driven by complex interactions involving - among other elements - agriculture,

rivers, canals, walls, peasant uprisings, the raising f

armies, barbarian incursions, taxation, civil service, power politics,

corruption, revolution, collapse and the emergence o

some new challenger from outside the established order. For us right now, the

point is that sometimes nomad rulers entered the Chinese heart and sometimes

the Chinese core took over the barbarian frontier. Every pulse would shake up

the borderlands, and send another tribe or two westwards. usually out of time,

out of history. As it happened, the fourth and early fifth centuries in north

China were chaotic, a time labelled by some historians the Sixteen Kingdoms of

the Fire Barbarians, the chaos diminishing somewhat when a Turkish group, the T'o-pa, established a kingdom known as Northern Wei in 396.

Did the chaos, much of it unrecorded, send shock waves of refugees westward,

forcing the Huns to move?

A cold snap in

central Asia or an invasion by this or that group of nomadic refugees cannot

explain why the Huns were inspired to conquer, and the others weren't. Why the

difference? Their success owes nothing to climate or the historical process,

and everything to their fighting skills.

Let's speculate about

their reasons for moving on the basis of what they lacked and what they had:

They lacked luxuries. They had the power to rob.

Pastoral nomads

produce more than enough for the necessities of life, but always lack luxuries,

if you ado the standards of the upper echelons of settled societies. Herds must

be led to new pastures. tents put down and up, pack animals and wagons loaded.

Possessions threaten mobility, and thus survival. Life on these terms is a life

without trimmings. You can see the results in Mongolia today, out in the

countryside no more than two or three hours from the capital.

Tourists easily buy

into this latter-day version of the noble savage, who drives his herds between

known pastures, living in an ageold seasonal rhythm.

But strip away the wind-powered generator, the motorbike and the TV; set aside

the school in the nearest town, where children can stay; return in winter, go

back in your imagination a century or two, imagine a life without fresh fruit

or vegetables (a problem even today in remote areas), and you will see how

nasty and brutish this life can be. Winters are lethal. An ice storm that seals

up the grass kills horses and sheep by the thousand. Not long ago, such a

catastrophe would leave families starving, without milk, meat or dung-fuel. At

one level, suffering and its corollaries - fortitude, strength, sturdy independence

- were a source of pride; at another, of envy. No wonder pastoral nomads looked

outwards.

In fact, looking

outwards was built into the way of life. Pastoral nomads were self-sufficient

for a few months, a year perhaps, but not in the long term. The evidence is

there today in Mongolia, as it was in the thirteenth century, as it had been in

the rise and fall of every nomad kingdom since before the Xiongnu.

To survive on the steppe, you need a tent, and to support a tent you need

wooden lattice walls and wooden roof supports. Wood comes from trees, and trees

come from forests and hills, not rolling grasslands. In addition, if you could

afford one, a two-wheeled wagon came in handy to carry the young and the old,

the tents and cauldrons and other possessions. Wagons, too, were made of wood.

For both tents and wagons, steppe herdsmen needed forests. To get wood you need

axes, which means iron, either made by local blacksmiths or acquired by trade.

And that is just for survival. In addition, nomads, being as human as the rest

of us, want refinements unavailable on the grasslands, like tea, rice, sugar, soft

and varied fabrics, especially silk: in brief, the goods produced by farmers

and more complex, urban societies.

Apply all this to the

area from which the Huns came, the Pontic and Caspian steppes. It was a

cauldron, a slow-motion seething of intermixed and successive peoples. Imagine,

then, our small group of Huns, buffeted from established pastures by a few bad

years or the ambitions of long-forgotten neighbours.

They move into new pastures, unwelcome as gypsies, despised, a threat to and

threatened by new and suspicious neighbours, lacking

both a homeland and the soft textiles, the carpets, the exotic drinking cups

and the jewellery that ease and enliven nomadic life.

Strip away the hospitality that acts as a security blanket for nomadic travellers and the reassuring knowledge of local pastures.

The Huns were

refugees wanting a base, a regular source of food, a renewed sense of identity

and pride in themselves. These were lacks that could be satisfied in only three

ways: by finding unoccupied land (no chance); or by some new arrangement with

established groups (tricky, with little to offer in return); or by force. The

future life they faced would be very different from that of the traditional

pastoral nomad, for once on the move, with no pastures to call their own,

trying to muscle in on the territories and trading arrangements of others,

with force as the only means of doing so, they were seated on a juggernaut that

would never find rest. For now, with every kilometre

westward, they would find pasturage increasingly reduced by settled

communities. They would, inevitably, become dependent on the possessions of

others. These might have been acquired by trade; but the Huns were less

sophisticated than their new neighbours. With little

to offer other than wool, felt and domestic animals, their only remaining

option would have been theft. They would turn from pastoral nomads into a

robber band, for whom violence would be as much a way of life as it became for

wandering Vikings.

The Huns were on the

move westward, away from the grasslands of Kazakhstan and the plains north of

the Aral Sea, wanderers who faced a choice between sinking into oblivion or

climbing to new heights by conquest. Conquest demanded unity and direction, and

for that we come at last to the final element in their rise to fame and

fortune: leadership. It was leadership that had been lacking before;

leadership that eventually released the Huns' pent-up power. Some time in the fourth century the Huns acquired their

first named leader, the first to bring himself and his people to the attention

of the outside world. His name was something like Balamber

or Balamur, and hardly anything at all is known about

him except his name. It was he who inspired his people, focused their fighting

potential to attack tribe after tribe, each of whom had their own strengths,

and each some weakness. For the first time, a great leader released the

tactical skills and established a tradition of leadership that would, in the

end. produce Attila.

The technical key to

Hun success however, was the Hun bow. Now, the bow certainly looks different,

because it is asymmetrical, like its Xiongnu prototype;

that is, when strung its upper limb is longer than its lower limb. Whether or

not the Huns inherited the design from the Xiongnu,

the design had been in existence for several centuries; it also spread

eastwards, to Japan. Oddly, asymmetry does nothing at all to the power, range

or accuracy of the bow; so its purpose remains controversial. Perhaps the length

of the bottom limb was reduced to ease handling, as it would when you whip it

over the horse's neck to fire to the right (or, if you are a real master, to

fire lefthanded). Perhaps it was easier to fire when kneeling; but when would

you need to kneel? Kassai, playing the mystic, wonders if, when drawn, the bow

became a symbol of the Hun tent, or the overarching deity, Heaven above, but it

doesn't really add up. I prefer to think of it as a matter of identity, for the

details of common objects often contain elements that emerge randomly or for

trivial reasons, and endure simply because they become traditional and there is

no good reason to change them. Perhaps Hun bows were asymmetrical because they

always had been, from the time when a stave newly cut from the tree was more

likely to be asymmetrical than symmetrical. Perhaps if you'd dared to ask

Attila why Hun bows were bigger at the top, he would have said through his

interpreter: That's the way we Huns make bows.

But Hun bows were

also different in two other respects, adding up to a third that really did

matter: they were bigger; they had a more pronounced recurve; and finally,

crucially, their size plus their shape gave them more power. The design evolved

in response to the changing environment of steppe warfare. The little Scythian

bow served well enough for 2,000 years until, in the third century BC, the

Scythians' eastern neighbours, the Sarmatians,

developed a defence against Scythian arrows. They

covered their warriors and horses with armour and

taught them to fight in close formation. There were various possible ways to

counter this - with swords, lances, javelins, heavy cavalry. But the most

effective was a bow that could punch arrows through armour.

This was the bow the Huns brought with them from the east - as we know from

those found in Xiongnu graves: a bow with a little

`wing' of horn, some 3 centimetres long, which curved

away from the archer. It was this, not the wooden frame of the bow itself, that

held the bowstring. The `wings' provided the weak ends with a rigidity that

wood on its own cannot match, as fingernails do things that bare fingers could

not. They also extended the length of the bow by a crucial few percentage

points; and the extra length increased leverage. This allows the archer to bend

a heavier bow with less effort, because the curving ear acts as if it were part

of a large-diameter wheel. As the archer draws the bow the ear unrolls, in

effect lengthening the bowstring. On release, the ear rolls up again, in effect

shortening the bowstring, increasing the acceleration of the arrow without the

need for a longer arrow and a longer draw. It was an invention that

foreshadowed the system of pulleys used in modern compound bows. In effect, it

gave the Hun archer longer arms, allowing him to shoot with slightly more

penetration, or a slightly greater range: a few metres

only, but a few crucial metres, enabling Hun arrows

to be fatal while those of their enemies died.

This beautiful and complex

instrument had another advantage. Making one demanded a level of expertise

amounting to artistry. This was no Kalashnikov, which could be churned out by

some Central Asian bow-factory. Recurved bows of any sort take a year or more

to make, but in addition the Hun bowyer had to be a master in carving and

applying the horn ears. Each bow was a minor masterpiece, and no other group

had the expertise to produce its match.

A superior bow,

however, was only one element in the Huns' dominance. It would be vital for the

lone warrior or the small raiding party; but, to an advancing horde,

small-scale victories were no more use than no victories at all. The Huns

needed to become a machine for massive and overwhelming destruction. One factor

in their favour was their nomadic lifestyle, which

gave them the ability to fight year-round, unlike western armies, which camped

in the winter and fought in the summer. Frozen ground and frozen rivers made

good going for strong men on strong horses. Their other major advantage was

that they learned to fight as one, and on a large scale. In their sojourn in

the wilderness or their drift westwards, they evolved tactics to suit their new

weapon. If Scythians could strike like the wind, the Huns learned how to strike

like the whirlwind.

In AD 350 the Huns

crossed the Volga. A few small, violent bunches of mounted archers led their

wagons and winding columns of horses and cattle into the grassland country

which survived little changed until Anton Chekhov saw it as a boy in the 1870s,

when he described the view that stretched out before the Huns, the

800-kilometre sweep of grassland from the Volga to the Crimea in, The Steppe.

In the mid-fourth

century this grassland was dominated by the Sarmatians, a loose confederation

of Iranian people who had taken it over from the Scythians more than 500 years

before. Much is known about the Sarmatians, because some of their art treasures

were found in western Siberia and handed over to Peter the Great of Russia.

They liked to make plaques of coloured enamels set in

metal showing fighting animals - griffins or tigers against horses or yaks: a

style that spread westward to the Goths and other Germanic tribes. The

Sarmatians specialized in fighting with lances, their warriors protected by

conical caps and mailed coats; no match for the Hun tornado.

One group of

Sarmatians were the Alans, a wide-ranging sub-federation known as As to the Persians. (It is from their name, by the way,

that `Aryan' is derived, l shifting to r in some Iranian languages; thus the

tribe so admired by Hitler turns out not to be Germanic at all.) Now we are

getting into a region and a tribe that became known to the Romans. Seneca,

Lucan and Martial mention them in the first century AD. Martial, a

sharp-tongued master of epigrams, skewered a certain Caelia and her

wide-ranging sexual habits by asking how a Roman girl could give herself to

Parthians, Germans, Dacians, Cilicians, Cappadocians,

Pharians, Indians from the Red Sea, the circumcised

members of the Jewish race and `the Alan with his Sarmatian mount', yet cannot

`find pleasure in the members of the Roman race'. The Alans raided south into

Cappadocia (today in north-eastern Turkey), where the Greekhistorian

and general Arrian fought them in the second century, noting the Alan cavalry's

favourite tactic of the feigned retreat (to be

perfected later by Hun archers). Ammianus says they were cattle-herding nomads

who lived in wagons roofed with bark and worshipped a sword stuck in the

ground, a belief which Attila himself would adopt. They were terrific riders on

their tough little horses. The Alans, more European than Asian, with full

beards and blue eyes, were lovers of war, experts with the sword and the lasso,

issuing terrifying yells in battle, reviling old men because they had not died

fighting. They were said to flay their slain enemies and turn their skins into

horse-trappings. Theirs was an extensive culture - their tombs have been found

by the hundred in southern Russia, many of them commemorating women warriors

(hence, perhaps, the Greek legends of Amazons). It was also a flexible one,

happy to assimilate captives and to be assimilated. Indeed, perhaps

adaptability was their main problem in the mid-fourth century: for they lacked

the unity to counter the Hun style of mounted archery.

The Huns blew them

apart, clan by clan. The Alans would soon form fragments of the explosion of

peoples which usually goes by its German name, the Volkerwanderung,

the Migration of the Tribes. However, while good assimilators, they also had a

talent for retaining their own identity. In the slurry of wandering peoples,

the Alans were like grit, widely mixed, but always abrasive. Within a couple of

generations, different clans would become useful recruits for the Huns, and

also allies of Rome. Their remnants in the Caucasus would transmute into the

Ossetians of southern Russia and Georgia: the first two syllables of this name

recall their Persian appellation, As, with a Mongol-style plural -ut (so the current name of the little Russian enclave known

as North Ossetia-Alania doubly emphasizes their roots). At the other end of the

empire, they would join both the Goths on their Visigothic

ruler as `king', he objected: a king ruled with authority, he said, but a judge

ruled with wisdom. Rome, having given up thoughts of direct rule, treated the

Visigoths as trade partners, valuing the supply of slaves, grain, cloth, wine

and coins. Some of them were Christian. A generation before the Huns arrived, a

Greek bishop, Ulfilas, had devised an alphabet for Gothic and translated the

Bible. But Christianity never won over the `judge' or the other aristocrats,

who were keen to preserve their own beliefs - the very essence of their own

sense of identity - in the face of the new cultural imperialism flowing from

Constantinople. After Valens acknowledged Visigothic

independence under Athanaric in 369, it seemed both would benefit: their agreement

established a mutual trade link, mutual respect, a buffer state for Rome

against the barbarian hordes of Inner Asia, freedom for Athanaric to do

whatever he wanted without fear of great-power intervention. What he wanted was

an end to Christianity. This he achieved by means of a sinister ritual

reimposing the old Gothic religion, which (as the historian Tacitus implies)

was centred on an earth-mother goddess, Nerthus.

Athanaric's officials wheeled a wooden statue of the goddess to the tents of

Christian converts and ordered them to renounce their faith by worshipping the

statue, on pain of death. Most chose to live, apparently, except a fanatic

named Saba, who was set on martyrdom. When he was declared a fool and thrown

out of his village, he taunted his fellow tribesmen until they threw him in a

river and drowned him by pressing him down with a piece of wood. He became, as

he would have wished, the first Gothic saint.

Rome and Christianity

could be resisted, then; but not the advancing Huns. Athanaric tried, setting

up a line of defence along the Dniester, but it was

easily bypassed when the Huns ignored the Gothic army, crossed the river by

night and made a surprise assault on the Goths from the rear. After a hasty

retreat across present-day Moldova, the Goths started to build a rampart along

the Moldovan border, the River Prut. It was at this point that Gothic morale

collapsed, driving them across the Danube into Thrace and starting the train of

events that led to the battle at Adrianople.

Behind them,

advancing from the Ukrainian lowlands, came Attila's immediate forebears, on a

75-kilometre march over the Carpathians, winding uphill along the road that now

leads from Kolomyya through the Carpathian National

Nature Park. It was the regular route for invaders, one used again almost 1,000

years later by the Mongols. You climb easily to 931 metres

(3,072 feet) over the Yablunytsia Pass (good skiing

in winter, pretty alpine walks in summer), then drop to the Romanian border,

and, leaving the Transylvanian highlands on your left, follow the snaking,

narrow road along the River Theiss onto the Hungarian grasslands.

For at least a

generation they have been on the move, living well off the proceeds of warfare.

They are hooked on pillage, not just for luxuries, but for sheer survival. It

is all they know. Now, suddenly, they are hemmed in. To the east lie highlands

- Transylvania and the Carpathians, through which they came a few years before.

There's nothing back that way for them. To the south and west lies the Danube,

the Roman frontier, with its armies and fortress-towns; to the north and west,

German tribes who may one day be vassals, but are not exactly rich. It will

take a little time to assess which way to turn. For newly arrived nomads, the

future is full of complexities and unknowns.

After Adrianople the

empire struggled, and failed, to remake the peace within and without. The

Balkans remained in turmoil, with Goth bands raiding freely, until the western

emperor, Gratian, and his eastern co-ruler, Theodosius the Great, made peace

with them all individually in 380-2, bribing them with tax exemptions, land

grants and employment in the armed forces. It was Theodosius who, at two vital

moments, held this tottering enterprise together by sending armies to back

Christianity against paganism and his family's claim to the West against

rebels. It was he who managed to buy time by converting the Goths into allies,

even if their version of Christianity was heretical. It was he who imposed the

Nicene version of Christianity empire-wide before his own death in 395. With

him fell a bastion against disorder and the infection of barbarism. His heirs

were two feeble sons, Arcadius (aged eighteen, ruler of the East) and Honorius

(eleven, of the West).

The empire became a

cocktail of cultures, interfused, each dependent on others. Some barbarians

settled; others kept on the move, notably the Visigoths. A new chief, Alaric,

took them raiding across the Balkans so successfully that he was made a

provincial governor, but that was just a steppingstone to a better homeland

for his people within the empire. In both parts of the empire, Goths and other

barbarians - even individual Huns - became senior officers. In the West, the

power behind the throne, Stilicho, a Vandal by descent, was married to a niece

of Theodosius. Goths served en masse, as contingents,

with the danger that their loyalty was to their own commanders rather than to

the emperor. Barbarians were fast becoming the arbiters of imperial destiny. In

401 Alaric led his Visigoths into Italy, forcing the emperor to move his court

to Ravenna, where it stayed for a century.

In 405-7 two

barbarian armies - ragbags of Goths, Alans, Vandals, Swabians, Alemanni and

Burgundians - swept into Gaul and Italy. Stilicho favoured

collaboration, provoking an anti-barbarian backlash in which he was purged and

executed, with no impact on the advance of the barbarians. In 410 Alaric seized

Rome. It was the first time the Eternal City had seen enemies within its walls

for 800 years - an event so shocking to Christians that it inspired the North

African bishop Augustine of Hippo to write one of the most influential books

of the age, Concerning the City of God. Alaric died that year, and his rootless

army, still in search of a homeland, drifted back to Gaul, then on into Spain,

finally swinging round again to settle north of the Pyrenees in what is now

Aquitaine. In 418 their new capital, Toulouse, became the centre

of a semi-autonomous region, a nation in all but name, supplying troops to the

empire in exchange for regular supplies of grain. Barbarian and Roman were

intertwined, in geography, arms, society and politics, a process exemplified by

the fate of the daughter of Theodosius and sister of Emperor Honorius, the

20-year-old Galla Placidia, who had been dragged off to become the unwilling

wife of a barbarian - Alaric's heir, Athaulf.

But fate allowed

Galla Placidia a remarkable comeback. When Athaulf died, she was married

(against her will, again) back into Roman stock, to a husband befitting her

status, the patrician and general Constantius, co-emperor for just seven months

in 421. It was this marriage that catapulted her into power, which she

preserved through many dramatic twists, turning herself into one of the most

formidable women of her age. When Constantius died, she was accused of intrigue

against her own brother and fled to Constantinople with her baby daughter

Honoria and her four-year-old son Valentinian, heir to the western part of the

empire. In Constantinople, the ruler in the East was Arcadius' son, another

Theodosius, who in 423 became, briefly, the sole ruler of the entire empire, at

the age of 22. Nevertheless, he chose to back Galla Placidia when she demanded

the western throne for young Valentinian. As a result, when the same year the

court in Ravenna chose to crown a non-family official, John, Theodosius sent an

army to crush the usurper, and placed Valentinian, now six, on the throne (thus

returning the boy's mother Placidia to Italy, along with the infant Honoria,

who is destined to play a peculiarly dramatic role).

This, then, was how

things stood when Attila was reaching maturity in the 420s: the empire divided,

both parts riven by religious and political rivalry, half a dozen barbarian

groups as immigrant communities, the northern frontiers in chaos, both armies staffed

in part by the very people they opposed. To an ambitious chieftain north of the

Danube, it all looked quite promising.

Nstorius the ex-Bishop of Constantinople had wrestled

with the central problem that divided Christianity in its early days - Was

Christ god, or man, or a bit of both? - and discovered what he considered - no,

knew - to be the truth: that, although Christ had been both god and man, he

possessed two distinct persons, because quite obviously the god part of him

could never have been a human baby. Therefore Mary could not have been the

Mother of God, since that would suggest that a mortal woman could produce a god,

which was a contradiction. Therefore, he, Nestorius, was right, and all

Christians who disagreed with him - namely, those who accepted the tenets laid

down at the Council of Nicaea in 325 and all other, antiNicaean,

heretics - were wrong.

The world had not

appreciated his insight. His great rival, Cyril of Alexandria, had had him

condemned and banished to Oasis, in the southern reaches of Egypt. There, as

the 430s wore on, he railed against the injustice done to him. He would be

revenged upon the lot of them - or, rather, God would on his behalf. Indeed,

divine vengeance had already started. How else to explain the rise of the Huns?

Once they were divided among themselves, and were no more than robbers. Now,

suddenly, they were united, and likely to rival Rome itself. This was surely

the Christian world's punishment for its `transgression against the true

faith'.

Nestorius might have

been shaky on the causes, but he was right in the grand sweep of the problem.

The Huns had indeed risen. Petty pillagers no longer, by the late 430s they had

become pillagers on a grand scale. In fact, this had nothing to do with God

backing Nestorius, and everything to do with the rise of our hero and

anti-hero, Attila.

For a decade after

Ruga's death in about 435, Attila's hands were tied by joint rule with his

elder brother Bleda. For those ten years the two would work together to

consolidate their kingdom, with Attila the junior, and increasingly resentful,

partner.

How and why they came

to power is a mystery. Of their childhood in the early years of the fifth

century nothing is known, and their names, both fairly common in Germanic, are

not much help. Bleda is a shortened version of something like Bladardus/Blatgildus. Attila

derives from atta, `father' in both Turkish and Gothic, plus a diminutive -ila; it means `Little Father'. The name even spread across

the Channel, into Anglo-Saxon. A Bishop of Dorchester bore it, and so did the

local bigwig recalled by the villages of Attleborough and Attlebridge

in Norfolk. It may not even have been our Attila's original name at all, but a

term of affection and respect conferred on his accession, a Hun version of the

pseudo-cosy dedyshka

('Granddad') by which Russians once referred to Lenin and Stalin.

At first all seemed

set fair for the two princes. They were at peace with western Rome, and settled

down to bind in local groups and focus on bleeding the East. Not that all was

sweetness. Ruga's death must have unleashed some nasty squabbling between the

brothers, who for the moment divided the kingdom between them, Attila taking

the downriver area in today's Romania, while Bleda governed in Hungary, the

forward territory with easier access to the rich west. Both must have demanded

commitment from their relatives and subsidiary chiefs, and done so with

menaces, because two royal cousins fled south, rejecting their own people to

seek refuge among their supposed enemies.

The year of Ruga's

death, Attila and Bleda together completed the peace agreed between their

uncle and the empire, riding south to the border fortress of Constantia,

opposite Margus, guarding the mouth of the Morava river where it joins the

Danube 50 kilometres east of Belgrade, just inside

today's Romanian border. Here they were met by Constantinople's ambassador, Plintha - a good choice, according to Priscus, for Plintha was himself a 'Scythian', a term that was used for

any barbarian or, as in this case, exbarbarian. Plintha and his number two, Epigenes,

chosen for his experience and wisdom, no doubt came prepared with a few wagons

loaded with tents and scribes and cooks and a lavish banquet, ready to flatter

with formality. The Huns, rough and ready and proud of it, were disdainful. As

Priscus writes, `The barbarians do not think it proper to confer dismounted,

so that the Romans [i.e. those from the New Rome, Constantinople], mindful of

their own dignity, chose to meet the Scythians [i.e. Huns] in the same

fashion.'

There was no doubt

who was in control. Attila and Bleda dictated the agenda; Plintha's

scribes took down the terms. All Hun fugitives would be sent back north of the

Danube, including the two treacherous princes. All Roman prisoners who had

escaped were to be returned, unless each were ransomed for 8 solidi, one-ninth

of a pound of gold (given that a Byzantine pound was slightly less than a

modern one, this was about $600 in 2004 gold prices), payable to the captors -

a good way of ensuring a direct flow of funds to the top Huns. Trade would be

opened, and the annual trade fair held on the Danube made safe for all. The sum

due to the Huns to keep the peace was doubled, from 350 to 700 pounds of gold

per year (about $4.5 million in current terms), the peace to last as long as

the Romans kept up payments.

As proof of their

good faith, the eastern Romans later handed over the two royal refugees, Mamas

and Atakam (`Father Shaman'). The manner of their

reception suggests both the vicious rivalry seething beneath the surface of

Attila's co-operation with his brother and the brutality of the times. The

princes were delivered on the lower Danube, at a place called Carsium (today the Romanian town of Harsova

in the Danube delta), straight into Attila's hands. There was no hope,

apparently, of winning their loyalty, to punish and make an example of them, he

had them killed.

It is clear from the

terms imposed by the Huns what they were after. Though they liked to melt down

gold coins for jewellery, they were also developing a

cash economy based on Roman currency, and there was no easier way to get the

cash than by extortion. They could offer horses, furs and slaves at the trade

fair on the Danube, but that would not bring real wealth - not enough to

acquire the silks and wines that would make life pleasant, or to pay for

foreign artisans who could construct the heavy-duty weapons upon which their longterm security would depend. Besides, it was only by

matching Roman wealth that they could avoid being ripped off. According to St

Ambrose, it was perfectly OK for Christians to bleed barbarians dry with loans:

`On him whom you cannot easily conquer in war, you can quickly take vengeance

with the hundredth [i.e. a percentage]. Where there is the right of war, there

is also the right of usury.' When Attila and Bleda returned to their own

domains, they had what they wanted in the short term - some gold, some

breathing-space; but peace did not serve their long-term interests. They neede war, and events elsewhere soon gave them opportunity.

During this decade,

disaster loomed on several fronts for both parts of the empire. Aetius was

fire-fighting in Gaul. quelling the Franks in 432, then the Bacaudae

(435-7). an obscure and disorderly band who fought a guerrilla war from their

forest bases, and finally the Goths, who almost tool: Narbonne in 437. In 439

Carthage itself, the old capital of Rome's North African estates, fell to the

Vandal chief Gaiseric. After 40 years of wandering - over the Rhine, across

France and Spain, over the Straits of Gibraltar - the Vandals had seized

present-day Libya only fourteen years previously. Carthage, with its aqueduct,

temples and theatres (one of which, named the Odeon, served as a venue for

concerts), was vandalized, in every sense. The invaders found their new

homeland, though fertile enough, rather a tight fit between the Sahara and the

Mediterranean, and quickly learned a new skill: shipbuilding. Carthage was

wonderfully located to dominate the 200-kilometre channel dividing Africa fro._ Sicily, and became a base for piracy, and then for a

navy. In 440 Gaiseric prepared an invasion fleet, landed in Sicily. did some

vandalizing, and crossed to the Italian mainland. intending no-one knew what.

From the East, Theodosius II sent an army to help repel the invaders, but he

was too late: the Vandals had headed home with their spoils before the

easterners arrived.

Attila and Bleda took

advantage of these desperate times. In the West they had a wonderful

opportunity for pillage. thanks to their alliance with Aetius, who needed them

to bolster his campaign against those unruly barbarians inside Gaul. There were

Huns helping to fight the Franks, and the Bacaudae,

and most memorably the Burgundians/Nibelungs. This was the tribe that had

crossed the Rhine almost en masse 30 years before,

leaving behind a remnant that successfully resisted the Hun attack. They had

settled, with Rome's unwilling agreement, on the Roman side of the middle

Rhine, taking over several towns, with Worms as their capital. Under their

king, Gundahar, better known to history and folklore as Gunther, they remained

a restless bunch, trying to take more land. An invasion westwards through the

Ardennes in 435 drew the attention of Aetius and his mercenary Huns, who had a

score of their own to settle after their defeat a few years previously. The

results were devastating, though no details of the assault survive. Thousands

of Burgundians died (though probably not the 20,000 mentioned in one source),

Gunther among them, in a slaughter that would be transformed into folklore,

notably in the great medieval epic the Nibelungenlied and in more recent times

by Wagner in his Ring cycle. Along the way, folk memory made the assumption

that Attila himself was behind the destruction of the Burgundians. That doesn't

fit. He had his hands full back home. But there is an underlying truth to the

legend, for there could have been no slaughter without an understanding between

Aetius and the Huns. Now they had their reward: vengeance, and booty. The few

surviving Burgundians were chased on west and south, their name clinging to the

area around Lyon and its vineyards long after the tribe itself and the later

kingdom had vanished.

Already, Attila and

Bleda needed more, if not from other barbarians, then from the eastern empire.

They had their pretexts ready. Tribute had not been paid. Refugees who had

fled across the Danube had not been returned. And, to cap it all, the Bishop of

Margus had sent men across the river to plunder royal tombs. (Priscus says they

were Hun graves, but the Huns made no burial mounds; they must have been

ancient kurgans, which had always been ransacked as if they were little

mountains to be mined at will.) The bishop should at once be surrendered, came

the order, or there would be war.

No bishop was handed

over, and Attila and Bleda made their move. Some time

around 440, at the trade fair in Constantia, Huns suddenly turned on the Roman

merchants and troops, and killed a number. Then, crossing the Danube, a Hun

army attacked Viminacium, Margus' immediate neighbour to the east, subjecting the town to an appalling

fate. No-one recorded why it was so vulnerable, but the townspeople seemed to

know what was in store, because its officials had time to bury the contents of

their treasury, over 100,000 coins which were found by archaeologists in the

1930s. The survivors were led away into captivity, among them an unnamed

businessman whom we shall meet again in rather different and much improved

circumstances. The city was then flattened, and not rebuilt for a century. It

is now the village of Kostolac.

Then the Huns turned

on Margus itself. The grave-robbing bishop, terrified that he would be handed

over by his own people to ensure their safety, slipped out of the city, crossed

the Danube, and told the Huns that he would arrange for the gates of his town

to be opened for them if they promised to treat him well. Promises were made,

hands shaken. The Huns gathered by night on the far bank of the Danube, while

somehow the bishop persuaded those on watch to open the gates for him. Right

behind were the Huns, and Margus too fell, and burned. It was never rebuilt.

What happened then is

unclear. Sources and interpretations vary so dramatically that no-one is

certain whether there was one war or two, or how long it, or they, lasted,

estimates varying from two to five years. Two or three seems to fit best. It

was all mixed up with the Vandals invading Sicily and the eastern army being

sent to help the West. There was much destruction in the Belgrade region. In

any event, the Huns were now in possession of Margus and its sister town,

Constantia, on the Danube's northern bank, and could dominate the Morava

valley, along which ran the main road into Thrace. Two other cities fell, Singidunum (Belgrade) and Sirmium

(now the village of Sremska Mitrovica, 60 kilometres

west of Belgrade up the River Sava), where the bishop handed over some golden

bowls that would, a few years later, become the cause of a nasty dispute.

Then something seems

to have stopped the Huns in their tracks - trouble at home, perhaps, or a rapid

offer of gold from Theodosius. Attila and Bleda pulled their troops out,

leaving the borderland of Pannonia and Moesia in smoking ruins. There was

another peace treaty, agreed by Anatolius, commander-in-chief of the eastern

empire's army and friend of the emperor.

It was perhaps as

part of this renewed peace that the Huns picked up another item of booty: a

black dwarf from Libya who adds a bizarre element to our story. Zercon was already a living legend. He owed his presence in

Hun lands to one of the greatest of Roman generals, Aspar,

who was in command. of the Danube frontier for a few years until 431, when he

was sent to North Africa in a vain attempt to quell the Vandals. It was Aspar who captured Zercon and

took him back to Thrace. Here he was either seized by the Huns or perhaps

handed over by Aspar. Zercon

was not a prepossessing sight. He hobbled on deformed feet, had a nose so flat

it looked as if it wasn't there at all, just two holes where a nose should be,

and he stuttered and lisped. He had had the sense to turn these deficiencies

into assets, and became a great court jester, specializing in parodies of Latin

and Hunnish. Attila couldn't stand him, so he became his brother's property.

Bleda thought Zercon was hilarious - The way he

moved! His lisp! His stutter! - and treated him like a pet monster, providing

him with a suit of armour and taking him along on

campaigns. Zercon, however, did not fully appreciate

Bleda's sadistic sense of humour, and escaped with

some Roman prisoners. Bleda was so furious that he ordered those sent in

pursuit to ignore all the fugitives but Zercon and to

bring him back in chains. So it was. At the sight of him, Bleda asked why he

had fled from such a kindly master. Zercon, speaking

in his appalling mixture of Latin and newly learned Hunnish, apologized

profusely, but protested that his master should understand there was a good

reason for his flight: he had not been given a wife. At this, Bledaa became helpless with laughter, and allocated him a

poor girl who had once been an attendant on his own senior wife.

For a couple of years

the Danube front remained quiet, Attila having discovered the benefits of

diplomatic exchanges. As Priscus tells it, Attila sends letters to Theodosius -

letters which must have been in Greek or Latin; the illiterate Attila must already

have had at least one scribe and translator, if not a small secretariat. He

demands the fugitives who have not been delivered and the tribute which has not

been paid. He puts a diplomatic gloss on what is little more than a gangster's

threat. He is a patient man. He is willing to receive envoys to discuss terms.

He also portrays himself as a man with a problem, namely his impatient chiefs.

If there is a hint of a delay or any sign that Constantinople is preparing for

war, he will not be able to hold back his hordes.

It seems that Attila

did indeed have a problem with some of his own people. Since peace was cheaper

than war, and ambassadors cheaper than armies, Theodosius sent an envoy, an

ex-consul named Senator. The land route was apparently too dangerous, for Thrace

was still a prey to freebooting Huns who had not yet been brought under

Attila's control, the `fugitives' he wanted returned by the terms of the Treaty

of Margus. So Senator opted to make the first part of his journey by ship,

sailing up the coast of the Black Sea to Varna, where a Roman contingent was

able to provide him with an escort inland. Senator duly arrived, impressing

Attila, who would later cite him as a model envoy, but nothing else seems to

have been achieved.

Perhaps something was

promised, for Attila rather took to the idea of exchanging envoys. His reason

for sending embassies had nothing to do with diplomacy and fugitives. This was

a gravy train for his top people, and a way to win time. It was not the issue

that was the issue, but the generous reception his ambassadors received, which

was something along these lines: My dear chaps, how wonderful to see you!

Fugitives? Tribute? All in good time. We'll talk after supper. Let us show you

to your rooms. Yes, the carpets and the silks are nice, aren't they - nothing

but the best. A glass of wine, perhaps? You like the glass? It's yours. Oh, and

after supper, there are the dancing girls. You've had a long journey. These

girls are chosen specially to restore the spirits of great warriors such as

your good selves. Priscus noted all this in rather staider terms: `The

barbarian [Attila] seeing clearly the Romans' liberality, which they exercised

through caution lest the treaty be broken, sent to them those of his retinue he

wished to benefit.' Four times in the mid-440s this happened, and each time a

retinue returned happy, with trinkets and cash as diplomatic gifts.

Neither side believed

in the peace. Constantinople was nervous - or so scholars surmise on the scanty

evidence of two laws rushed into effect in the summer and autumn of 444.

Landowners had long been required to supply recruits from their tenantry, or pay

cash in lieu. But senior officials, most of them also landowners, were exempt;

that was a perk of their high office. Now, by one of the new laws, they too had

to provide troops, or pay a fine. The second law was a 4 per cent tax on all

sales. Clearly, the city needed more men in arms and the money to pay them.

And, according to one of Theodosius' edicts, the Danube fleet was being

reinforced and the bases along the river being rebuilt.

The emperor was in

fact quite right to expect trouble, because he was about to give the Huns cause

for complaint. He had no intention of losing more money to the barbarians. In

the succinct words of Otto Maenchen-Helfen, one of the greatest of experts on

the Huns, `To get rid of the savages, Theodosius paid them off. Once they were

back, he tore up the peace treaty,' and simply cut the payments dead.

Perhaps it was this

crisis that inspired Attila to make his move for absolute power. He would by

now have had his own power base, in the form of an elite referred to by Greek

writers as logades (we will meet half a dozen of them

in person later, in the company of the Greek diplomat Priscus), and the inner

circle would already have been in place, or Attila would not have been able to

grab supreme power. Among them were his deputy, Onegesius;

Onegesius' brother Scottas;

some relatives (we know of two uncles, Aybars and Laudaric);

and Edika, the leader of a tribe immediately to the north, the Skirians, now in alliance with Attila's Huns, whose foot

soldiers would henceforth form the heart of the Hun infantry. They were all

bound to Attila by something more than fear of his brutality, for they must

have equalled him in that. This was the man who would

best serve their interests, and those of the Huns as a whole. They were a

substantial group, these logades. Historians have

debated whether they are best seen as local governors, policemen, tribute

collectors, priests, wise men, shamans, military commanders, clan leaders,

nobles or diplomats. Probably, each played several roles. The implication is

there in Liddell and Scott's Greek-English Lexicon: logades

is the plural of Togas,`picked, chosen'. Lowdes means `picked men': the elite. As farmer's wife

named Jozo Erzsebet - Elizabeth Jozo - was tending her turkeys when she saw

that they had scratched up something glittery from the subsoil. She stooped

down, scratched a little more, and found a mass of gold coins: 1,440 to be

exact, together weighing 64 kilos. Her son cannily took one of them to the

National Museum in Budapest and offered to sell it. They gave him 1,500

forints, the equivalent of about two months' wages. Next day, he turned up

again with another two coins. At this point the museum curators realized that Mrs Jozo's turkeys needed expert attention. The treasure

was whisked off to the museum, pictures were taken of Mrs

Jozo in her headscarf and the shallow pit - the picture is still there in the

Szeged museum - and the family was left richer by 70,000 forints, enough to buy

two houses.

The coins are

Byzantine, minted by Theodosius II, and a good proportion of them are dated

443, right when Attila and Bleda started sending their ambassadors on their gravytrain missions to Constantinople. Finds like this are

an invitation to imagine. Why would someone bury coins like this in a field,

with no other goods? Here is a possible scenario. Attila has just made his

move. Bleda is dead. He too had his logades. Most of

them are also dead now, but one has escaped. Like the unfortunate royal cousins

whose skeletons for years graced the sharpened stakes downriver, he thinks his

chances will be better if he flees across the Danube. He gathers his share of

the latest payment to arrive from Constantinople and heads south. But then, all

of a sudden, he sees horsemen ahead of him, and behind. He's surrounded. He

doesn't give much for his chances if he's caught with the cash on him. Hastily,

he buries it. He will take shelter with peasants, and hope to fade into the

landscape until things calm down, when he will retrieve his loot and build

himself a better life somewhere else. Does he survive? I doubt it, because he

never returns, and the hoard lies hidden for 1,500 years, until scratched up by

Mrs Jozo's turkeys.

Today we know about

Atilla primarily because of Priscus' Byzantine History. Priscus was the

only one to have met Atilla in person, and his story starts with the

arrival of Attila's envoys at the court of Theodosius II in Constantinople in

the spring of 449. The eminent team is led by Edika, the ex-Skirian

leader and now Attila's loyal ally, who has performed outstanding deeds of war.

Orestes, a Roman from the strip of land south of the Danube now under Hun

control, is the second senior member of the party, with a small retinue of his

own, perhaps two or three assistants. Orestes, though rich and influential, is

one of Attila's team of administrators. He is always being sidelined by Edika

and resents it.

Orestes reads the

letters he took at Attila's dictation, and Vigilas,

the court interpreter, translates. In summary, Attila tells the emperor what he

should do to secure peace. He should cease harbouring

Hun refugees, who are cultivating the no-man's-land that he, Attila, now owns.

Envoys should be sent, and not just ordinary men, but officials of the highest

rank, as befits Attila's status. If they are nervous, the King of the Huns will

even cross the Danube to meet them.

In the end Atilla is

bought of for cash on a scale never seen before.

Attila withdraws from the lands south of the Danube. And now Attila is free to

turn his attention to a softer target than Constantinople - the decaying empire

of Rome. And although Rome itself was too tough a nut to challenge head-on

- its northern province, Gaul, was a softer target.

In 418 it acquired

its own local administration, the Council of the Seven Provinces, asserting

Roman-ness and Christianity from its new capital, Aries (still today a city

rich in Roman remains), dominating the Rhone delta. It was here that Aetius had

based himself as Gaul's defender from 424 onwards, standing as firmly as

possible first against the Visigoths, but also against the Germans on the Rhine

frontier. Of course, to do so he employed some of the very barbarians he was

opposing - as he also did in his own cause: when Aetius, the defender of Gaul

against Franks and Huns, was fired by the regent Galla Placidia in 432, he led

a rebellious army of Frank and Hun mercenaries to force his reinstatement. In

450 Aetius was still playing the same role, his power spreading along Rome's

network of roads to garrison towns like Trier guarding the Moselle valley, and

Orleans, holding the Loire against Visigoths to the south, and the wild Britons

and Bacaudae of the north-west. This was, however, a

province on the retreat, guarding its core. The Rhine, the old frontier, had

its line of forts, but they were beyond the Ardennes, and hard to reinforce in

an emergency.

Military force and

Aetius formed only half the equation. For the other half, the cultural bit, we

may turn to Avitus, statesman, art lover and future emperor. He was to be found

15 kilometres south-west of Clermont-Ferrand, in the

steep volcanic hills of the Massif Central, beside a lake formed when a

prehistoric lava flow blocked a little river. Romans called the lake Aidacum. In undertaking the invasion of the West, the Huns

faced a problem similar to that which faced the Germans as they prepared to

invade France in 1914, and again in 1939. Approached from the Rhine, France has

fine natural defences in the form of the Vosges

mountains, giving way to the Eifel and Ardennes in the north. Practically the

only way through is up the Moselle, through what is now Luxembourg, and then

out onto the plains of Champagne. But it was no good making a thrust through

the mountains into the heart of France (or Gaul) if the army could be

threatened from the north - from Belgium or, in this case, the region occupied

by the Franks.

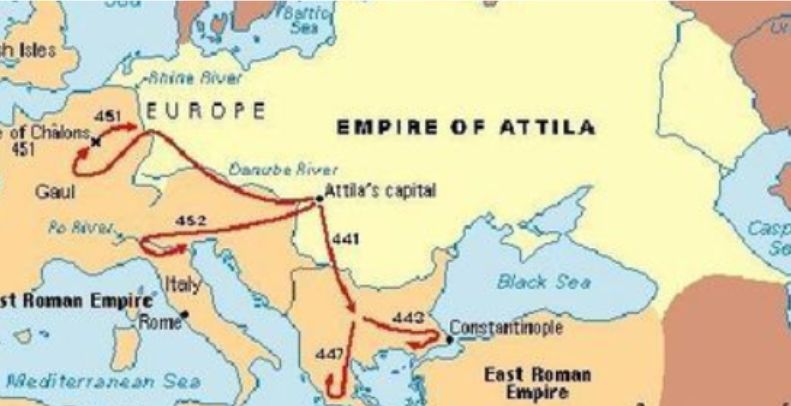

Early in 451 Attila's

main army advanced up the Danube along frontier tracks, spreading out on either

side, crossing tributaries over fords or pontoons of logs cut from the

surrounding forests. One wing seems to have swung south and then up the Rhine,

via Basel, Strasbourg, Speyer, Worms, Frankfurt and Mainz, then meeting the

main force, which followed the old frontier from the Danube to the Rhine.

Next, Attila's troops

would have entered Troyes. It was too good a source of supplies to ignore. No

doubt looting had already started, inspiring a legend in which fact and fiction

are hopelessly mixed, but which is often presented as history. According to

Lupus' official biography, he saved his city and his people by confronting

Attila, a meeting that involved one of the supposed origins of a famous phrase.

Assuming the meeting took place, how Lupus introduced himself is not recorded,

but it presumably included something like: I am Lupus, a man of God. At this,

Attila came up with a smart one-liner, in impeccable Latin: “Ego sum Attila,

flagellum Dei' - `I am Attila, the Scourge of God.”

This was, of course,

a Christian interpolation, made because Attila's success demanded explanation.

It would have been inconceivable that a pagan could prevail over God's own

empire, against God's will. Therefore, pagan or not, he must have had God's backing,

the only possible explanation being that Christendom had not lived up to divine

expectations and was being punished for its lapses.

The battle of

the Catalaunian Plains that followed, was not a

Stalingrad, a turning point that stopped a barbaric invader in his tracks,

instead, it was more of a Hunnish Dunkirk, at which a great army escaped

to fight on. Orleans had been the turning point, as Attila had seen when he

avoided action and turned around; but it led to no definitive conclusion.

Thereafter, for a couple of weeks, he was working to keep his army intact. The Catalaunian Plains was a rearguard action, forced upon

Attila when he was already in retreat.

By autumn 451 Attila

was back in his Hungarian headquarters, with its wooden palace, its stockaded

houses, Onegesius' bath-house, and its encircling

tents and wagons. Would he then have been happy to sit there, enjoying the loot

brought back from the campaign in Gaul? A different character might have been.

He might have learned his lesson, settled down to consolidate an empire that,

if nurtured, would have created a lasting counterpart to Rome and

Constantinople, trading with both. But Attila was no Genghis Khan, willing to

plan for stability.

Thus he soon would

making another deeper trust into the Roman empire, only to die, on his (next)

wedding night. Seldom has a girl become so famous for doing nothing.

In Greek and Latin, she was Ildico, which

historians equate with the German name Hildegunde. Atilla died from a hearth attack, plus an overdose of wine no doubt.

His body was placed

out on the grassland, lying in state in a silken tent in full view of his

mourning people. Around the tent circled horsemen, `after the manner of circus

games', while one of Attila's senior aides delivered a funeral dirge, which

seems to have been repeated to Priscus word for word, though of course

translated from Hunnish into Gothic and then Greek, from which Jordanes

produced a Latin version, from which at last this version comes:

Chief of the Huns,

King Attila, born of his father Mundzuk, lord of the bravest tribes, who with

unprecedented power alone possessed the kingdoms of Scythia and Germany, and

having captured their cities terrorized both Roman empires and, that they might

save their remnants from plunder, was appeased by their prayers and took an

annual tribute. And when he had by good fortune accomplished all this, he fell

neither by an enemy's blow nor by treachery, but safe among his own people,

happy, rejoicing, without any pain. Who therefore can think of this as death,

seeing that no-one thinks it calls for vengeance?

These lines have

inspired much analysis, even some attempts to reconstruct a Gothic

version, to little effect. It is impossible to prove if it had a genuine

Hunnish source, let alone if it captured anything of the original. But Priscus

surely believed it did, or why would he have quoted it so exactly?

Perhaps he was eager

to do a good job of reportage that does something to record the Huns' grief,

albeit nothing much for their poetic abilities. The best Attila's people can

say of him, apparently, is that he pillaged on a massive scale, and died without

giving them an excuse to kill in revenge for his death. The description

continues with a ritual lamentation, a sort of wake, a display of both grief

and celebration of a life well lived. Jordanes, or Priscus, says that the Huns

called the rite a strava, which, as the only single

surviving word that could perhaps be Hunnish, has been the cause of much

hopeful speculation. Scholars arguing for over a century agree on one thing:

Turkish it isn't, which means almost certainly that it was not after all

Hunnish. According to several experts, it is a late-medieval Czech and Polish

word for `food' in the sense of a `funeral feast', though whether the Huns had

adopted it 1,000 years earlier, or whether Priscus' informant used the term in

passing, is a mystery.

Then, when night

fell, the body was prepared for burial. The Huns did something to which we will

return in a moment, `first with gold, second with silver and third with the

hardness of iron'. The metals, Priscus says through Jordanes, were symbols -

iron because he subdued nations, gold and silver for the treasures he had

stolen. And then `they added the arms of enemies won in combat, trappings

gleaming with various special stones and ornaments of various types, the marks

of royal glory'.

What was it that was

done with the metals? Most translations say they bound his `coffins' with them,

from which flows a ludicrous but often-repeated story that Attila was buried

inside three coffins, one of gold, one of silver, one of iron. Gibbon accepts

the legend as fact, without comment. As a result, generations of

treasure-hunters have hoped to find a royal tomb containing these treasures.

This idea previously

was widely accepted here in Hungary - partly due to the account in Geza Gardonyi's novel, The Invisible Man, no doubt.

However it's nonsense

if you give it a moment's thought. How much gold would it take to make a

coffin? I'll tell you: about 60,000 cubic centimetres.

This is $15 million worth in today's terms, a solid tonne

of gold: not much in terms of modern production or in terms of the empire's

annual gold output, but still the equivalent of a year's tribute from

Constantinople (which, remember, had dried up long before). If the Huns had had

that much gold, Attila would never have needed to invade the west, and he would

by now have had a good deal more than a wooden palace and a single stone

bath-house. And, if they had it, is it really conceivable that they would do

anything so dumb as to bury it all?

In fact the director

of Szeged's museum, now named after him, the Mora Ferenc Museum, traced the

story back to a nineteenth-century writer, Mor Jokai, who in turn took it from

a priest, Arnold Ipolyi, who in 1840 claimed he had it from Jordanes, at a time

when very few people had access to Jordanes. More likely, he had heard of

Gibbon's account. Anyway, Ipolyi either failed to understand, or deliberately

improvised for the sake of a good story.

If you look at what

Jordanes actually wrote, there were no metal coffins. The Latin suggests a more

realistic solution: coopercula ... communiunt, `they fortified the covers'. No mention of

arcae (coffins), although the word is used in verbal form later in the account.

Now it begins to make sense. We may, at the most, be talking of a wooden

coffin, into which are placed a few precious items like the slivers of gold

used to decorate bows. The lid is then sealed with small, symbolic golden,

silver and iron clasps. As it happens, there are precisely such coffins among

the Xiongnu finds in the Noyan Uul

hills of Mongolia.

Within the next ten

years later, those Huns that remained (survived), merged with other tribes

or scattered slowly eastwards, dissipating like dust after an explosion,

sinking back into the dreamtime from which they had emerged a century before.

Then again, in the

last two decades of the fourteenth century and the beginning of the fifteenth,

now the Mongols, blazed through Asia and E.Europe.

Cities were razed to the ground, inhabitants tortured or/and decapitated.

If you ever go to

Mongolia, watch what you say about Genghis Kahn. Among Muslims, and European

Christians, he was a marauding savage, but to the people of Mongolia he is a

visionary leader who created international law, abolished torture, granted

religious freedom and developed the first and a highly efficient international

postal system.

On the right a hotel in today’s Mongolia, on the left

one of the views

For updates

click homepage here