By

Eric Vandenbroeck

Waiting for my transit flight at Yangon airport, I ponder about the

first time I visited Burma (when traveling in the outback of Myanmar was much

more restricted the now) that coincided with what since came to be known as the

Saffron Revolution.

In

2007 masses gathered amid suddenly inflated fuel prices in Myanmar to protest

against the ruling military dictatorship. The protestors were joined by thousands

of Buddhist monks.

Since then, and more particular in 2012, we have seen the rise of

another, very different kind of monks. Monks

active in the 2007 protests recently also rebutted allegations leveled

against them by anti-Muslim firebrand U Wirathu in

what is called a clash of the clerics in Mandalay.

Already in 2003 I posted how the attacks

against the Rohingya developed.

Societal unrest, whether it be communal tensions or ongoing conflict

with ethnic armies, provides a prime opportunity for any military to reassert

its waning influence. Already this has worked to surprising effect in a country

where ethnic and political divides run deep.

The accumulated hatreds and resentments from

the colonial era deeply influenced all the most malevolent and divisive

policies of the Burman generals after 1962. But, sadly, even in this new era of

a supposedly reforming Burma, those same hatreds and resentments are still

being exploited in Rakhine State. After two bouts of vicious ethnic cleansing in 2012, about 140,000 of an

estimated 1.1m Rohingyas fled into refugee camps. They

have not been allowed to leave. The festering antagonism between the

Rakhine and the Burmans, on the one hand, and Rohingya on the other, still

carries enormous political consequences for the future of Burma.

The epicentre of this conflict is the city of Sittwe, the tropical capital of western Rakhine State.

Originally called Akyab, it was once the capital of

the prosperous and independent-minded kingdom of Arakan, founded in 1531, a centre of trade on the Indian Ocean. But all this came to

an end when Arakan was conquered by the Burman kings in 1785. Oppressed by the

Burmans, who took twenty thousand Arakanese captives back to the new royal

capital of Amarapura, Arakan was then the first

province to be overrun by the British, advancing eastwards from Bengal at the

start of the first Anglo-Burmese war.

Under British rule Akyab, with its excellent

riverine port on the Kaladan, yet also facing onto the Bay of Bengal, quickly

became an even more important trading post than it had been in the past. And

so, like Rangoon, it consequently sucked in thousands of immigrants looking for

work and opportunities, eventually becoming the fourth largest city in colonial

Burma.

There had been Muslim immigration to Burma before the British arrived,

but that had been relatively small-scale. The British were recording numbers of

Muslims in the mid 1820s in Arakan who had clearly

been living there for several generations.

But the fact that at least some of the so-called Rohingya can trace

their roots back in Sittwe to well before the British

arrived does not impress the Rakhine. Uninterested in the nuances of the

situation, they just want them all out of the way – and preferably out of the

country.

The slogan of the first significant Burmese nationalist movement, the Dobama Asiayone (“We Burmans”),

was “Burma for the Burmans”. The struggle against British rule from the early

1920s took, from the beginning, two forms: against the relatively small number

of British rulers and officials, and against the millions of their Indian and

other colonial satraps. In some respects, the campaign to vanquish white

colonial rule was relatively pacific compared to the violence that began to be

visited on the Indians. Anti-Indian riots broke out in 1930 in the Rangoon

dockyards and again in 1938, during which hundreds of Indians were killed

throughout the country. The British colonial authorities set up a Riot Enquiry

Committee that published its report in 1939, attributing the main cause of the

bloodletting to incitement by the pro-Buddhist Burmese media. The recent

outbursts of savagery in Sittwe against the

descendants of many Muslim and Indian immigrants, starting in June 2012, show

how old, festering prejudices can be exploited to trigger what became wholesale

ethnic cleansing.

The violence has not just affected Muslims who may identify as Rohingya.

While the international community has seemingly confused all

"Muslims" with "Rohingya" in Myanmar, this is not the

reality. Many Muslims in Myanmar do not self-identify as Rohingya. The Muslim

population is highly diverse, and many identify as "Burmese

Muslim".

Simmering ethnic and religious tensions are clearly being exploited by

misguided monks, political groups, and the remnants of the dictatorship to gain

power. It is said that some of the worst monks may be Secret Service men who

have taken robes and are deliberately stoking fears to turn people back to the

military.

Underneath

burning of a Rohingya village

No one is sure who has been orchestrating the anti-Muslim riots. Seen as

an arm of the security forces(USDA)- the Swan Arr

Shin- (which translates as Masters of Force) are thought to be the main agents

provocateurs, the mysterious outsiders who turn up in places like Mandalay to

stoke up feelings, shout slogans against Muslims and possibly kill a few of

them.

One figure often accused of backing Wirathu and 969 is Aung Thaung, a

parliamentary member of the ruling USDP and a former junta minister of industry

who in October was placed on the U.S. Treasury Department's sanctions blacklist

for "intentionally undermining" Myanmar's political reforms. Aung

Thaung, the close friend and henchman of Than Shwe, known to be close to the

Swan Arr Shin.

Aung Thaung was

blacklisted by America just before President Obama’s second visit to Myanmar,

for an Asia summit in November 2014. “By intentionally undermining the positive

political and economic transition in Burma, Aung Thaung is perpetuating violence,oppression and corruption”, read his official US

Treasury citation. The psywar arm of military intelligence has been publishing

anti-Muslim material for decades, so it is possible also that some of the

current material being circulated emanates from the military. Aung Thaung is

also known to be close to some of the monks of Mandalay, and has been connected

in particular to the most notorious of the chauvinist, nationalist monks, the

poisonous and outspoken Ashin Wirathu.

Many Muslims blame the Swan Arr Shin for

inciting and carrying out much of the anti-Muslim violence of the last few

years. Their Muslim victims note how well trained and well organised

their assailants often are, and how they will be brought in from out of town in

cars and small buses. These hired hands often use the same weapons – clubs,

blades and torches – against Muslims that they had previously employed against

the NLD, and also against the monks during the Saffron Revolution in 2007.

If former Saffron Revolution leader Gambira's memory is accurate, Wirathu

apparently admitted that he is under pressure from a government official to

create disturbances between Bhuddists and Muslims.

To be clear, anti-Muslim sentiment is not a new phenomenon in Myanmar

and is rooted in its pre-independence history. However throughout the military

junta in Myanmar, the escalation of anti-Muslim hate speech aimed to instigate

Buddhist-Muslim riots in order to deflect the people’s anger and exasperation

away from the military regime.

A scholar who has been researching this for many years, Christina Fink,

wrote: “Throughout military rule in Burma, successive regimes have used the spectre of a Muslim takeover to whip up nationalist

sentiments. In particular, when anti-Regime tensions are running high,

incidents of intolerable behaviour by Muslims always

seem to pop up and are used to channel anger into conflicts.” And that; “There

were also several reports of people seeing monks with walkie-talkies under

their robes, and a few had very shiny heads indicating they had just been

shaved. In other words, it was widely believed that military men dressed as

monks were involved, although many real monks did most of the damage.” (C.Fink, Living Silence: Burma Under Military Rule, 2001, p.

225, p. 219.)

A former member of Myanmar's Military Intelligence service described how

she witnessed agent provocateurs from the army provoke problems with Muslims:

"The

army controlled these events from behind the scenes. - They paid money to

people from outside."

Among other findings is a confidential document warning of 'nationwide

communal riots' that was deliberately sent to local townships to incite

anti-Muslim fears.During half a century of military

rule, Myanmar's feared Special Branch and Military Intelligence agencies were

vehicles for monitoring opposition and, where necessary, crushing dissent.

The secret arms of the regime were notorious for infiltrating and

manipulating rivals by turning them against each other.

According to Mary Callahan, a high priority was given to psychological

warfare. In this context Mary Callahan, was given access to the archives of the

Tatmadaw of the 1950s, and she has

written that “over the next decade, psywar initiatives included… sponsoring pwe (traditional variety show) performances, radio shows

and pamphlet publication and distribution.” (Mary Callahan, Making Enemies: War

and State Building in Burma, Cornell University Press, 2005, p. 183.)

Another example was a notorious book that circulated in the early 2000s

propagating lies and myths about Islam and Muslims. It was full of spurious

references and footnotes, to give it an air of authenticity, and was made

widely available. It was intended as a sort of Buddhist Burmese version of The

Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an earlier hoax purporting to expose the world

conspiracy for Jewish domination. One of the leading themes of the book is also

that the dislike of Muslims is based on “intermarriage,” which is seen as

eroding Buddhists’ racial and religious purification.

Right after the distribution of the book and its copies, anti-Muslim

riots erupted on 15 May 2001 in “Taungoo” which is in “Pegu” division,

considerably lower part of Myanmar that resulted in the deaths of about 200

Muslims, in the devastation of 11 mosques and the burning of 400 houses were

destroyed by fire.

The distribution of anti-Muslim pamphlets in 2001 was conducted by the

“Union of Solidarity and Development Association” (USDA) which later became

USDP (Union of Solidarity and Development Party), a government-sponsored organisation that carries out social and political affairs

for the military (Human Rights Watch, 2002). The state thus actively or

passively sponsored the anti-Muslim sentiment and propaganda in order to

maintain their power or redirect anger and frustration from the people. By

manipulating and escalating anti-Muslim sentiments that instigated the mass

violence against Muslims, the military had a chance to show their importance

for the country’s security.

Similarly also with the anti-Muslim riots of 2012 of which an

investigative report concludes that Burma’s

large and much feared military intelligence service, the Directorate of Defense

Security Intelligence, is commonly believed to have had agents working within

the monk-hood.

The government portrayed the violence of 8-12 June 2012 in Rakhine state

as spontaneous inter-communal fighting. However, evidence derived from ISCI

interviews with Rakhine Buddhist perpetrators suggests that in fact the

conflict involved planned, highly organised

state-sanctioned attacks.

The violence was carried out with apparent impunity. When asked directly

how many perpetrators had been successfully prosecuted for the June 2012

violence in Sittwe, the Attorney General for Rakhine

state said: ‘None … it happened at night time so there is no evidence’.

(Interview with U La Thein, Rakhine state Attorney General, Sittwe).

He reported that the police had closed all their investigations. Witness

testimony suggests that state security forces were involved in extrajudicial

killings, rape, sexual assault and torture. (As quoted in “All

You Can Do is Pray”)

Some days before the violence erupted, Rakhine activists sent letters to

the administrators of the Rakhine village tracts in the Sittwe

hinterland. The letters urged each household to send at least one man between

the ages of 20 and 40 to participate in the planned attacks on Rohingya

neighborhoods, while others were to remain behind in order to defend their

village in case of retaliatory attack. The men were to be ready on the morning

of 8 June to be collected and bussed in to Sittwe.

They were informed that it was their duty as Rakhine to participate in an

attack on the Muslim population and so they armed themselves with knives and

bamboo spears in anticipation of the arrival of ‘express buses’. Hundreds if

not thousands of Rakhine men and women were transported to Sittwe

by these buses. Some were dropped off near Nasi village and joined in the arson

attacks on the houses there. Most Rohingya fled for their lives; some tried

vainly to defend their homes and families. The Rakhine perpetrators were

dropped off at the bus station and at various designated points around the

town. They were instructed to block fleeing Rohingya from all routes except

those that led to the diesel electricity generators and on toward the camp

complex area. While in Sittwe, Rakhine perpetrators

were given free meals and returned to their villages at around 4pm each day.

The transport and catering required high levels of organization and funding.

Rohingya survivors and Rakhine participants identified local Rakhine businessmen,

Rakhine civil society leaders and ANP politicians as the chief organizers.

There is no doubt that the 969 movement is well funded and well

organized. It has its own weekly newspaper (by some seen as influenced by the

psywar department), which regularly attacks Islam and other religions such as

Christianity.

Since 2012 Wirathu and other 969 protagonists have enjoyed almost

complete freedom, unlike the rest of the population – “the government allows

them to do anything they like.” Many of the allegations on Wirathu’s notorious

Facebook page, the main conduit for his hate-speech, are usually no more than

cleverly concocted and provocative lies. The post on 1 July about the rape of a

Buddhist woman, for instance, which sparked off the violence in Mandalay,

rapidly turned out to be a complete fabrication. The 969 movement has also

inspired a wider Buddhist organization called the Association for the

Protection of Race and Religion, known as Ma Ba Tha

in Burmese. This is a more broad-based affair and is consulted by the Ministry

of Religious Affairs on draft legislation affecting issues of “race and

religion”. This movement is supported by the money of one of the regime’s

wealthiest cronies, Khin Shwe.

In 2014, President Thein Sein himself asked parliament to draft

legislation based on four proposals for new laws that emanated directly from

the Ma Ba Tha. Thus, the president has become closely

associated with their agenda. All the proposals sought to limit further the

rights of Muslims in Burma and to divide Muslims from the Buddhist majority.

Much of the proposed legislation, especially the prospective Buddhist Women’s

Special Marriage Bill and the Religious Conversion Bill, would violate even the

existing Burmese constitution, let alone contravene international norms on

human rights. When the UN Special Rapporteur for human rights in Burma attacked

the four proposed laws for just this in early 2015, she was savagely denounced

by Wirathu. According to press reports, he called her a “bitch” and a “whore”.

The government portrayed the violence of 8-12 June 2012 in Rakhine state as

spontaneous inter-communal fighting. However, evidence derived from ISCI

interviews with Rakhine Buddhist perpetrators suggests that in fact the

conflict involved planned, highly organized state-sanctioned attacks.

The Myanmar government has been responsible for a series of key

decisions to remove all but the most rudimentary healthcare services from the

Rohingya in Rakhine state. Removal of healthcare is a powerful means of

weakening a community. First, the

government expelled Doctors Without Borders, which had been providing

health care for the Rohingya.

In February 2014 Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF Holland), the only

provider of emergency referrals and healthcare services to Rohingya in northern

Rakhine state, was

expelled from Myanmar following the announcement of their treatment of 22

Rohingya victims in the northern Rakhine State village of Dar Chee Yar Tan

following a concerted attack by local Rakhine. The government denied reports

that a massacre had taken place and expelled MSF from Myanmar for making false

and ‘provocative’ claims. Then orchestrated mobs attacked the offices of

humanitarian organizations, forcing them out.

Discussions with a range of informants indicated that there is no

government monitoring of disease or health services in the Rohingya camps,

villages and Aung Mingalar. This represents conscious

neglect and indifference by the Myanmar state to the health of its Rohingya

inhabitants. Together, the action and inaction of the authorities provide

compelling evidence of the deliberate creation of a humanitarian health crisis.

For the Myanmar State, untreated disease and medical complications are a

powerful form of unwanted population control.

The monks of Mandalay are, on the whole, well-meaning and thoughtful

people. They can see straight through Wirathu, and understand the anti-Muslim

campaign for what it really is.

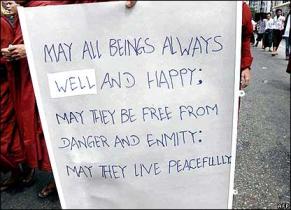

Buddhist monks in Yangon, Bago, and Mandalay are beginning to speak out

by using Buddhist doctrine to challenge intolerant messages. Buddhist monks

have been known to engage with interfaith groups to mediate between Buddhist

and Muslim communities, and some monks were reported to have even sheltered

Muslims during riots in central Myanmar in 2013. Prominent monks, such as Sitagu Sayadaw, have led the movement to promote tolerance

through public statements countering the vocal 969 movement. In addition, respected

monks Ashin Seikkeinda and Ashin Sandadika

have led inter-faith gatherings, which have created space for lower-ranking

monks and lay people to speak out and challenge the hitherto dominant

narratives of hate, fear, and exclusion. Unfortunately, while these nascent

movements begin to garner support for religious tolerance, security concerns

thwart their progress. But monks and activists face threats for speaking out

too loudly for religious tolerance. For example, in June 2014, anonymous

threats of riots and property destruction caused the organizers of Myanmar’s

Human Rights Film Festival to

withdraw a documentary about an improbable friendship between a Buddhist

woman and a Muslim woman during the 2013 ethnic violence in the town of Meikhtila.

For the 2014 Census in Myanmar (the first since 1983) the government

banned the word Rohingya (declared stateless) and asked recognised

Muslims to register themselves as “Bengalis” instead of Muslim. Also in Kachin

and Karen states enumerators failed to do a complete census tipping the balance

towards a larger ethnic Burmese population.

As for an impetus for change from outside Myanmar, to date, the

international community has failed to take decisive action to end the crimes

against humanity in Rakhine state in favor of political and economic engagement

with the current Thein Sein government.

Myanmar furthermore has blocked

attempts by member states to address the Rohingya issue within the context

of ASEAN. Last month (16 November 2015) Amnesty

International issued a statement requesting this stonewalling should

change.

Unfortunately also during last

month’s election process anti-Muslim "It's time for change" flyers

were distributed to whip up sectarian fears to the benefit of the ruling

Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), the political arm of Myanmar's

powerful military.

By protecting the minority Muslim's and Rohingya on the other hand,

Myanmar could set the stage for also protection of its Chin and Kachin

Christian minority groups, which “have

long been subjected to threats, intimidation, and discrimination, including the

burning of churches.” Religious intolerance threatens Myanmar’s nascent

transition to a more open, democratic state.

Sadly, though, such are the appalling levels of ignorance among most,

particularly young, Burmese, that the lies and rumors circulated by the 969

movement have been believed all too easily. In a society where for decades

there was almost no media available except for the few desultory government-run

press and TV outlets, few have the wherewithal to analyze social media, for

instance, critically and objectively. Furthermore, the drip, drip, drip of

fanciful and malicious propaganda merely reinforces many people’s existing

prejudices.

Of the nearly half a million monks and nuns in Burma, those espousing

hatred and supporting violence are a handful, less than one percent. But the

state sponsored fear and prejudice resonates.

Fact is that the overwhelming majority of both urban and rural Rakhine

want to live peacefully with their Muslim neighbors. These Rakhine

overwhelmingly believe the government and military are more responsible for the

conflict. They

therefore believe the state has the power to fix the issue whenever it is

willing.

For updates click homepage

here