By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

Manufacturing Holiness

Although our six-part

investigation about Chinese spy operations had been a long time in the making,

we decided to go ahead the day top officials from the U.S. Justice Department

partly to send out a warning unveiled a slate of indictments against 13 Chinese

nationals accused of spying on behalf of Beijing.

As for the subject

we covered in Part Two, today, Chinese police stations in the

Netherlands were ordered

to close immediately, and the British government announced today

it would step up work to prevent “transnational repression” as police

investigate reports of undeclared Chinese “police stations” around the

country.

"Because no

permission was sought from the Netherlands" for the stations, "the

ministry informed the (Chinese) ambassador that the stations must close

immediately," Dutch Foreign Minister Wopke Hoekstra said on

Twitter. The first Chinese office was opened in June 2018 in Amsterdam by

the Lishui region police force, while Fuzhou. operates another in

Rotterdam.

In Part Three, we described how the Ministery Of State

Security (MSS) could lure in foreign friends from the highest levels. And in

Part Four, we described the

circumstances that allowed past MSS spy operations to thrive.

Today 2 October, Xi Jinping's tenure at the helm of the CCP has

coincided with remarkable economic, social, and political developments in

China. Boasting the world's second-largest economy, China will likely soon

surpass the United States in economic development and output.

With this rejuvenated

authority, the CCP advocates a political agenda characterized by overt

nationalism. This nationalism promotes a modern and state-centric

constructivist narrative that predicates China's global ambitions upon support

for this ideology. China's modern nationalist political narrative focuses on

China's degradation and difficulties during its recent past and present

reality.

At the same time,

China's image abroad has declined significantly in the past several years, a

sharp reversal from its relative popularity, for example, in Africa, Asia, and

Eastern Europe.

Today, we will go

into an unusual episode of how the Chinese spy agency Ministery Of State

Security (MSS) foraged into using a Buddhist Temple. Its statue has three

aspects: one side faces inland, and the other two face the South China Sea.

One Tempel For All

Guan

yin, originally a male (Avalokiteśvara) bodhisattva, is Buddhists'

great uniter. Unlike other higher beings worshipped in China, Guan yin is a

feature of the Theravada traditions of Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Myanmar. When

the Hainan statue was unveiled in 2005 after six years of construction, more

than a hundred senior monks from China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau gathered

in resplendent robes to celebrate its completion.

The Shanghai Connection

Ji

Sufu stood proudly before Guanyin, out of place

in his stark white dress shirt and black pants.

Ji had been at the

heart of the scheme since its inception in the 1990s.

But why was Ji, a

nondescript businessman from Shanghai with little apparent interest in

Buddhism, conducting this orchestra? He was secretly working for the Shanghai

State Security Bureau (SSSB), one of the MSS's most aggressive and

internationally active units. The Shanghai bureau is notorious for running

long-term operations to infiltrate foreign governments and boasts substantial

cyber espionage capabilities. In 2004, it pushed

a Japanese diplomat to suicide after blackmailing him over his affair with

a karaoke bar hostess. Not long after, it paid an American university student

in Shanghai to

apply for jobs in the CIA and State Department, which scared the US

intelligence community off hiring people with significant experience in China. In

recent years, it’s approached numerous US current and retired government

officials, scholars, and journalists, successfully recruiting some and paying

them to hand over sensitive information.1

From the beginning,

corruption, mystery, and spies defined the Nanshan Guanyin project. The Party

secretary had his connections to China’s security apparatus: a decade earlier,

he ran the Ministry of Public Security, a counterpart to the MSS that carries

out counterintelligence work. Before then, he was a leading official in

Shanghai, perhaps explaining why the SSSB’s prints were all over the temple.

The Shanghai State Security Bureau (SSSB)

Today, the company

that owns and runs the temple complex is filled with an odd assortment of

Shanghainese men and women. Xu Yuesheng, general manager and Communist Party

secretary of the company, also sits on the board of the SSSB charity that

Nanshan Temple funds. Government records show he’s attended charity meetings

inside the agency’s headquarters. Another document claims that he works for a

technology company, Shanghai Tianhua Information Development Co., which also

uses the bureau’s Ruining Road headquarters as its address.2 If someone turns

up behind an intelligence agency’s closely guarded walls and works for one of

its front companies, they’re probably an intelligence officer.

Four other suspected

SSSB agents sit among the company’s leaders in Hainan. Feng Fumin is one of

them. He once headed the agency’s Political Department, a senior leadership

role overseeing the smooth operation of the SSSB Party committee and domestic

propaganda to improve the agency’s image. As one of the bureau’s most senior

Communist Party officials, Feng would be trusted to maintain discipline while

covertly dealing with religious organizations and companies.2

Despite the bureau’s

leading role in the Nanshan Guanyin company, business records make it look like

it only owns a meager 0.7 percent stake through one of its front companies. Two

investment firms own the rest from Shanghai and Hong Kong.

Both trace back to Wu

Feifei, who started her business career as an executive in what remains one of

the MSS’s main front companies, China National Sci-Tech Information Import and

Export Corporation. Wu owns the corporation’s Shanghai branch and controls more

than two dozen subsidiaries specializing in property development, investment,

and Buddhist tourism.3 As for the Hong Kong company, Wu and SSSB officers such

as Xu Yuesheng own most of it.4

All roads, it seems,

lead to the SSSB, which reaps income from Guanyin and the Nanshan Temple. While

the Nanshan Temple makes regular donations to the bureau through its charity,

those are dwarfed by its large payments to the agency’s front companies.

According to the Nanshan foundation’s financial reports, it paid out ¥174

million (A$37 million) to SSSB-controlled companies in 2019. In contrast, about

¥3 million (A$600,000) went to the temple.

MSS’s Spy Monks

Master Yishun, the

abbot of Nanshan Temple and head of its MSS-backed charity, is the face of a

new breed of Chinese Buddhists. More in tune with the pronouncements of Xi

Jinping than Buddha’s words, Yishun stands out with his unabashed flattery of

the country’s communist leadership. After the 19th Party Congress in 2017, he

bragged that he’d hand-copied Xi Jinping’s tedious speech three times. ‘I’m

planning to write it out ten more times,’ he added in an address to Hainan’s

peak Buddhist association, which he chairs. One needn’t speculate at his

comparison to sacred sutras, which the faithful often transcribe as a kind of

meditation, for Yinshun believes ‘the 19th Party Congress report is a contemporary

Buddhist scripture’. Assuming he writes a rapid forty characters a minute, he

must have set aside a full day for each copy of Xi Jinping’s doctrine.

If this is the new

Xiist sect of Buddhism, Yishun is its high priest and international ambassador.

Yishun concluded, after meditating on Xi Jinping Thought: ‘Buddhist groups must

consciously protect General Secretary Xi Jinping’s core status, practicing the

principles of knowing the Party and loving the Party, having the same mind and

morals as the Party, and listening to the Party’s words and walking with the

Party.’5 Yinshun has added a litany of political titles alongside his Buddhist

honorifics. As a vice president of the China Buddhist Association, he is

effectively a senior co-opted of the United Front Work Department, which

controls the association. Yishun also chairs the official Buddhist associations

of Shenzhen and Hainan province.

Most importantly,

he’s a delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the

country’s peak united front forum.6The role technically makes him a political

advisor to China’s Party-state. In practice, he is merely a cog in its united

front machine, faithfully working towards the Party’s goals – a cadre in monk’s

robes. Buddhism made in China The MSS was also behind another bold Buddhist

venture, Yinshun’s Nanhai Buddhist Academy. In 2017, Buddhist leaders from

across Asia visited Hainan Island to celebrate the academy's opening, situated

in the same complex as the Guanyin statue.

Guests gathered

before a temporary stage in the construction site that was to become an

institution of Buddhist learning. The shells of many of the complex’s buildings

stood around the visitors, but it was hard to imagine the full splendor Yinshun

planned for his school. Sheets of green mesh were strewn across the newly

excavated hillside to keep the dust down. Over 6000 controlled explosions had

already been deployed to carve out terraces and pathways for the academy.

Mock-ups showed a stunning complex of modernist but unmistakably Chinese

buildings, with secluded meditation halls and dormitories to house more than a

thousand monks from faraway nations. A central promenade faced the sea, leading

down the hillside before ending in a jetty where visitors would arrive by boat.

More than 200 monks had already signed up for the academy’s degree program.7

Like the Guanyin and

Yinun’s Nanshan Temple, this state-of-the-art academy belongs to the SSSB.

Between 2019 and 2020, at least RMB66 million (A$14 million) of the academy’s

funding has come from the temple charity controlled by the SSSB.8 To Indian

observers, the announcement was an embarrassing reminder of their government’s

failed bid for international Buddhist influence. Nanhai Academy compares to

Nalanda, a famous medieval Indian Buddhist university that once received

visitors from as far away as Korea 9. A few years earlier, the Indian

government tried to resurrect Nalanda, drawing high-profile figures like Nobel

laureate Amartya Sen as advisors. Yet the university opened with eleven

teachers, fifteen students, and no campus. In the meantime, classes were held

in a government-owned convention center while students stayed in a hotel.10

Construction carried on at a snail’s pace in India, while the Nanhai Academy’s

main structures were already in place upon its unveiling in 2017.11 The

symbolism of China beating its southern neighbor in the race to resurrect an

ancient Indian Buddhist institution is painfully clear.

As a further snub to

India, the Nanhai Academy eschews Sanskrit, a canonical language of Buddhism.

The Sanskrit lexicon has left a significant mark on modern Chinese because

Chinese Buddhist sutras are believed to be translations of Sanskrit originals

mostly. The academy instead offers programs in the Chinese, Tibetan, and Southeast

Asian Pali traditions of Buddhism.12

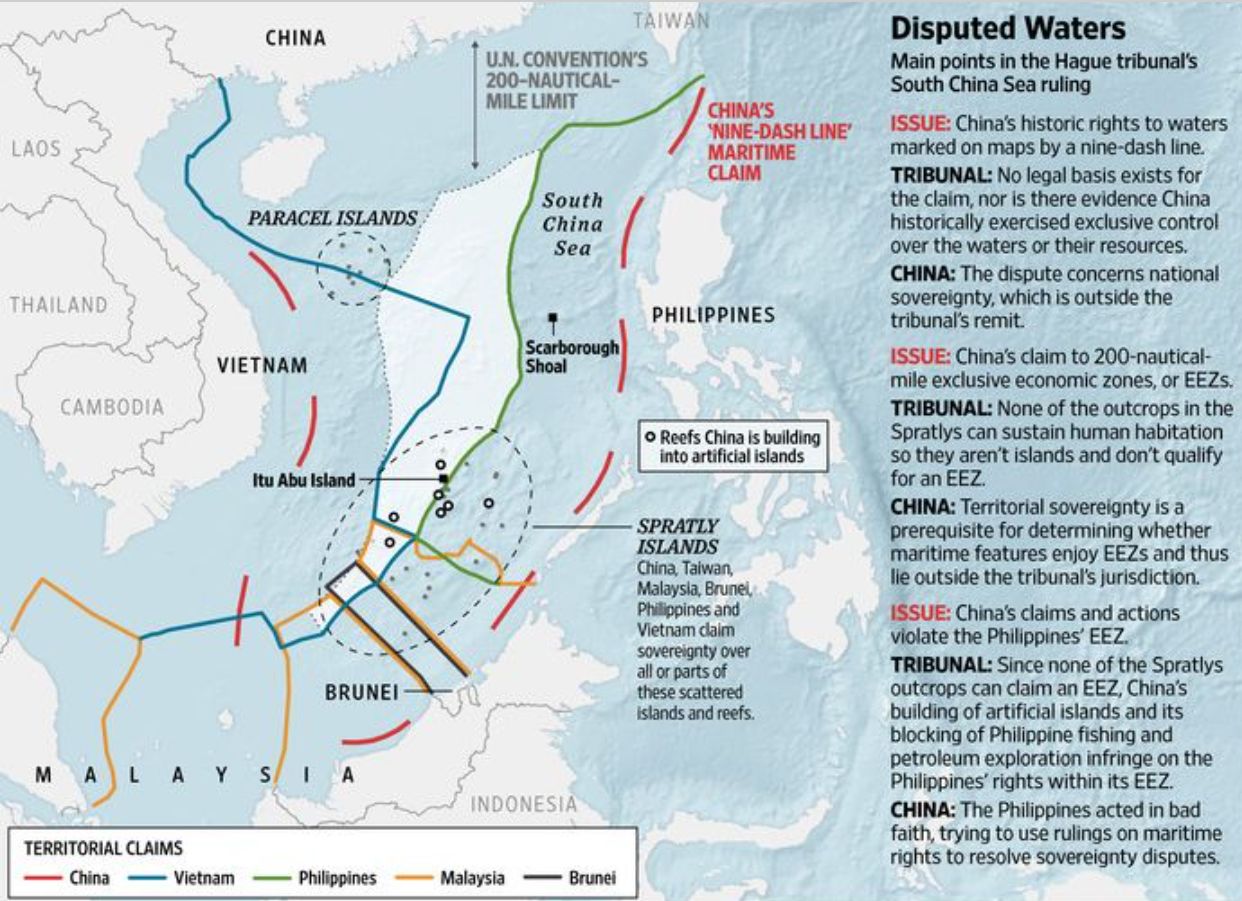

China has a more

specific reason for keeping Indian influence out of the Nanhai Academy. Nanhai

means ‘South China Sea, where China has illegally occupied and militarised

coral reefs, simultaneously angering and belittling countries like Vietnam, the

Philippines, and Malaysia, which also have claims to the waters.13 The

nine-dash line, a vague yet ludicrously expansive border China claims over the

South China Sea, represents a touchy dispute that the Party wants to keep the

Indian government out of. As scholar Jichang Lulu writes, ‘The Academy’s

international orientation does not conceal its PRC patriotic character,’ and Xi

Jinping’s political agenda defines its activities. Its creation has coincided

with the emergence of a bolder global Buddhist policy’ under General Secretary

Xi Jinping.14 Through its international exchanges, the academy functions as a

base for Buddhist influence efforts designed to sign up Buddhist leaders to the

CCP’s strategic vision.15 The United Front Work Department, the agency in

charge of religion in China, sits at the heart of China’s Buddhist influence

program. Under Xi, it has formally subsumed the country’s religious affairs

agency in a move designed to strengthen the Party’s control over religion.16

The department currently supervises an ungodly mix of Buddhism, Christianity,

Islam, communism, and political ambition. While it uses holy men to peddle the

Party’s agenda abroad, it runs informant networks within Chinese temples,

mosques, and churches, working with security agencies to stamp out foreign

influence over religion in China.17 Officially, the Nanhai Academy is

subordinate to Hainan’s UFWD. Its deputy dean is not a priest but a local

united front system official.18

While the UFWD’s

agenda is clear – to manage and spread China’s global Buddhist presence –

precisely what MSS officers gain from their stake in the academy is tightly

under wraps. Even Yinshun is unlikely to be informed of their operations

through his temples and the academy. Nonetheless, it’s hard to imagine spies

missing the opportunity to profile and recruit foreign Buddhist students across

Asia. They would be stupid not to ride on Yinshun’s coattails, watching if not

actively guiding his political influence operations throughout the

region.

Indeed, China’s

Buddhist influence activities in the region are growing much more targeted and

state-driven, according to Southeast Asia scholar Gregory Raymond.18 By

training the next generation of monks and building personal relationships with

influential abbots and temples in the region, Yinshun has declared that the

Nanhai Academy will ‘create a sinicized Buddhist system’, reinventing Communist

China as the sole global axis of Buddhism.19 Just as China seeks dominance over

the South China Sea, Yishun explained that his ‘South China Sea Buddhism’

concept is one ‘with China’s Buddhism as its core, radiating out broadly’

across the region and exporting schools of ‘Made in China Buddhism’.20

China’s history of

Buddhism, shared with much of the region, helps it claim shared values, or even

a shared future, with other Asian nations.21 ‘South China Sea Buddhism

establishes the cultural foundation for the South China Sea region’s community

of common destiny,’ Yinshun wrote in a detailed report to the Chinese

government.22

To this end, Yinshun convenes an annual gathering of world Buddhist

leaders, including those from Taiwan, the United Kingdom, the United States and

Canada, called the South China Sea Buddhism Roundtable.23 Designed to promote

the Party’s political vision, the event focuses little on Buddhism except as

it’s relevant to Party ambitions. In 2019, former Japanese prime minister

Hatoyama Yukio, who Party influence agencies have repeatedly feted, issued the

roundtable’s opening address, reportedly offering his full support for the Belt

and Road Initiative.24 Yinshun’s speeches at the event are framed around Xi

Jinping’s trademark foreign policy concept: building a ‘community of common

destiny for mankind’ with China at its core.25 As China expert Nadège Rolland

explains the clunky phrase ‘reflects Beijing’s aspirations for a future world

order, different from the existing one and more in line with its interests and

status.26

Yinshun seeks to implement the spirit of Xi Jinping’s ideology

by ‘raising the discourse power of China’s religious sphere on the

international stage. He claims that attendees to the roundtable have ‘confirmed

the position that the South China Sea is China’s, and that China has already

become the core of world Buddhism.’ In reality, the memorandum signed by

attendees contains no such language. That’s not to say many wouldn’t

wholeheartedly agree with Yinshun’s claim. Foreign delegates to the roundtable

often issue praise of the Belt and Road Initiative and ‘Buddhism with Chinese

characteristics’ or pledge their commitment to the ‘One China Principle.’

One Buddha, one

China, and one thousand targets Yinshun primarily

targets countries such as Mongolia, Thailand, Cambodia, and Myanmar with deeply

Buddhist populations. In those lands, religious leaders often legitimize

political leaders or speak out against them, such as when monks in Yangon

refused to accept state military donations.

Mongolia’s

Sainbuyangiin Nergüi is one of Yinshun’s closest foreign contacts. He is the

abbot of a temple in the capital of Ulaanbaatar. He sends many of his monks to

train in China Yinshun has appointed him a guest professor at the Nanhai

Academy and invited him to the South China Sea roundtables. At the 2017

roundtable meeting, Nergüi spoke more of international relations and economics

than religion, tying the event to politics in ways that might make even Yinshun

blush. After emphasizing Mongolia’s adoration for the Belt and Road Initiative,

he praised China as ‘the leader of world Buddhism.’

Nergüi

sees Yishun and the Party as ushering in a new era of Buddhism, asking them to

‘further and more tightly unite the world’s Buddhist groups and formulate

policies on the religion. He highlighted one of the policies in particular:

‘All lamas and countries that believe in Buddhism support the one-China

policy,’ he said. ‘We only have one Buddha, and we support the one-China

policy. Therefore, we attend this event.’ In other words, agreement with the

Party’s policies is tantamount in importance to belief in Buddhism, and

attendees to Yinshun’s events are hitching their religious credibility to the

Party’s political beliefs. Detailed in the research of independent scholar

Jichang Lulu, Nergüi’s case highlights how Buddhist influence quickly reaches

the profane realms of politics and moneymaking. The abbot belongs to a large

and well-connected family, and his siblings have flourished as local elites.

During one of Yinshun’s visits to Mongolia, he was greeted by representatives

of a major construction company headed by one of Nergüi’s brothers, who was an

Ulaanbaatar city councilor until his conviction on embezzlement and

abuse-of-powers charges in 2009. Not the most virtuous company for Yinshun to

keep, but the potential for political influence opportunities is undeniable.

Another brother, previously posted to China as a diplomat, has risen to the top

of Mongolian politics. After serving as mayor of Ulaanbaatar, he was appointed

deputy prime minister in 2021, taking the lead on Mongolia’s relations with

China.

While these

operations are most effective in Buddhist nations, Buddhism has a strong appeal

and following in the Western world. And Chinese abbots have a unique ability to

disarm foreign guests, despite China’s history of religious repression and the

scandals rocking its Buddhist establishment, notably when the head of the

national Buddhist Association resigned after sexual harassment allegations in

2018.

In particular, Yinshun has maintained ties to the United Kingdom; former

prime minister Tony Blair delivered a video message to Yinshun’s 2020 South

China Sea Roundtable. Yishun first traveled to the country in 2015, speaking at

the House of Lords and touring Cambridge University. The Nanhai

Academy has partnered with Cambridge to set up a joint digital Buddhist museum.

Yishun couldn’t resist claiming a political victory for China here. After the

museum project began, he unveiled a ‘Cambridge Research Institute for Belt and

Road Studies in Hainan, even though Cambridge’s website does not refer to its

existence.

Yishun has also

visited Australia several times. On one trip, he met billionaire united front

figure Huang Xiangmo, a prolific donor to Australian political parties and head

of an organization advocating for China’s annexation of Taiwan. According to

media reports, Huang’s visa was later canceled by Australia’s

counterintelligence agency because they found him ‘amenable to conducting acts

of foreign interference.

The MSS isn’t the

only intelligence agency that works with Yinshun, nor the only one cultivating

foreign religious groups. A front group run by Chinese military intelligence,

the China Association for International Friendly Contact, has included the

abbot in its international exchanges. For decades, this military intelligence

front has maintained close ties to a Buddhist-inspired Japanese New Age

religion called Agon Shū.

It’s not humor or

faith that lies behind the SSSB’s embrace of Yishun and Hainan’s Buddhist

community but cold calculus. From a relatively undeveloped place without any

notable history of Buddhism, Shanghainese intelligence officers built Hainan

Island into a leading platform for Buddhist influence efforts. The Guanyin

colossus is a testament to the agency’s creativity, resourcefulness, and

long-term planning. Buddhism is a window into how the MSS seeks to use religion

to influence and infiltrate countries with different political environments to the

United States. The case indicates that intelligence agencies covertly drive

those who already raise eyebrows for their international influence efforts and

united front work.

Reactions To China's Spy Operations

Australia was an

unlikely first to cross the point of no return. The country relies heavily on

trade with China, although US companies still lead in investments.27 Xi Jinping

toured the country in 2014, and Australia’s political establishment boasted

strong ties to Chinese officials and Party-linked businesspeople. Political

interference and united front work were a distant and obscure vocabulary. That

is until a series of contingent events in 2017 jolted the country into action.

Early that year, backbench politicians rebelled against ratifying an

extradition treaty with China.28 In June, investigative journalists produced

the most detailed and revelatory reports the public had seen into CCP-backed

interference in Australian politics.29 By the end of the year, the prime

minister, armed with findings from a classified study into the Party’s covert

influence operations, tabled new laws that gave security agencies powers to

intervene in such activities.30 The government also began contemplating banning

Huawei from the nation’s 5G network.31

This was much more

than a readjustment of the Australia–China relationship. It was a tectonic

realignment, the effects of which continue to play out—waking up to the threat

of political interference called into question the Party’s intentions and

goodwill. It also brought an understanding of the CCP and its ideology into the

heart of discussions about China when their contemporary relevance had long

been downplayed.32 Recognising the innocence with

which much of the country previously engaged with China meant that the field

was now open for a re-evaluation of the place of economic ties, research

collaboration, education exports, and human rights in the China relationship.

Nothing about waking up to this was easy or inevitable. China’s retaliation –

economic coercion, arbitrary arrests of Australians, and ending high-level

exchanges with the Australian government – only confirmed Australia’s growing

reliance on China was fraught.33 This new paradigm doesn’t mean giving up on

the benefits of exchanges with China. As John Garnaut, a key architect of

Australia’s foreign interference strategy explained, It’s about sustaining the

enormous benefits of engagement while managing the risks.

Australia is now seen

as both a model for countering foreign interference and a canary in the coal

mine, sending out warnings of the CCP’s coercion and covert activity. Slowly

but surely, the misguided assumptions and narratives that informed decades of

engagement with China are being discarded. The MSS operations that propped them

up for so long are being unwound. Even in Australia, this process still has

many years to go. The country’s capacity to shine a light on interference,

enforce foreign interference laws, deter covert operations, and build the

resourcing and expertise needed to inform those efforts are still being

developed.

Though no other

political system has ‘reset’ its relationship with China as suddenly as

Australia, aggressive responses to the Party’s espionage are ramping up across

the globe. In 2021, the CIA, still struggling to collect intelligence after the

MSS dismantled its networks a decade earlier, announced the creation of a new

mission center dedicated to China operations.34 Daring spy-catching operations

have seen FBI agents go undercover to pose as MSS officers to meet with

suspected spies.35 (The bureau has come a long way. More than two decades ago,

it directed an employee who only spoke Cantonese, and not Mandarin, to

impersonate an MSS officer.)36 Current and former US government employees have

been charged with spying for China in recent years. Baimadajie

Angwang, an officer of the New York Police

Department, was charged in 2020 with acting as an agent of the United Front

Work Department.37 US prosecutors have also accused more than a dozen MSS

hackers of espionage, although it’s almost certain that none will ever face

court.38

The United States is

not alone as it clamps down on Chinese espionage. In 2021, governments

worldwide teamed up to point the finger at the MSS for widespread hacks of

Microsoft Exchange servers.39 All large nations hack each other, but the MSS

‘crossed a line, in the words of Australian cyber chief Rachel Noble, by

letting cyber criminals move in behind it to steal and extort.40 Australian

authorities have accused a Melbourne-based united front figure of working with

the MSS to influence a sitting politician. Many other suspected foreign agents,

including two Chinese academics, have had their visas canceled.41 The UK

government has expelled three MSS officers pretending to be journalists.42 It

officially named lawyer and political donor Christine Lee as an agent of

influence for the United Front Work Department.43 German authorities have

charged a political scientist with working for the Shanghai State Security

Bureau.44 Japan, which still lacks laws against espionage and interference,

publicly blamed the Chinese military for cyber attacks

and announced the creation of new police units to counter technology theft and

cyber espionage.45 In 2021, Estonia, a Baltic state normally under constant

threat from Russia, convicted a spy for China.46

Other PRC

intelligence agents and covert influence plots have been exposed in France,

Taiwan, New Zealand, Belgium, Poland, India, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka,

Kazakhstan, Singapore, and Nepal.47 All that in a few years.

This list of

counterintelligence actions is at once reassuring and unsettling. For every MS

spy who’s caught or whose case is leaked to the media, dozens, if not hundreds,

continue to operate. Few of these cases touch upon the CCP’s influence

operations. But maybe that’s about to change.

Continued in Part Six

1. Mara Hvistendahl,

‘The friendly Mr Wu’, 1843 Magazine, 25 February 2020,

www.economist.com/1843/2020/02/25/the-friendly-mr-wu; ‘Ron Rockwell Hanson

felony complaint’, US Department of Justice, 2 June 2018,

www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1068176/download; Office of Public

Affairs, ‘Former State Department employee sentenced for conspiring with

Chinese agents’, US Department of Justice, 9 July 2019,

www.justice.gov/opa/pr/former-state-department-employee-sentenced-conspiring-chinese-agents;

Nate Thayer, ‘How the Chinese recruit American journalists as spies’, Nate

Thayer [blog], 1 July 2017,

web.archive.org/web/20170703131210/http://www.nate-thayer.com/how-the-chinese-recruit-american-journalists-as-spies/; interview

with an American scholar.

2. Feng Fumin (冯馥敏) was appointed to the SSSB Political Department role

in 2002 and first headed its charity in 2012. ‘大事记 2002年8月’, 《上海党史与党建》, October

2002, http://www.doc88.com/p-2844358531556.html; 上海民政局, ‘准予上海新世纪社会发展基金会基金会变更登记决定书’, 上海社会团体管理局, 26 November 2012, archive.today/kjlKf. State security organs’ political departments, among

other things, may oversee domestic propaganda efforts designed to improve the

image of state security work and encourage cooperation from the general public.

3. Shanghai Shangke Enterprises (上海上科实业总公司) was originally a branch of China National Sci-Tech

Information Import and Export Corporation (中国科技资料进出口总公司), which is still covertly owned by the MSS. The

company ultimately owns nearly 54% of Sanya Nanshan Pumen Tourism Development (三亚南山普门旅游发展有限公司). In the late 1990s, Wu Feifei

(吴菲菲) was the chairwoman of China National Sci-Tech

Information Import and Export Corporation, which was registered to an address

in Shanghai at the time. Its address has moved between cities, including

Tianjin, for unclear reasons. ‘中国科技资料进出口总公司’, Kanzhun, no date; 中国工商企业咨询服务中心 (ed.), 《中国企业登记年鉴: 全国性公司特辑 1993》, 中国经济出版社, January 1994, p. 306; ‘三亚南山普门旅游发展有限公司’, QCC, no date.

4. Hong Kong’s A.P.

Plaza Investments Limited (亞太投資有限公司) ultimately owns 39.80% of Sanya

Nanshan Pumen Tourism Development (三亚南山普门旅游发展有限公司). It includes Li Kam Fu aka Li Jinfu

(李锦富) and Xu Yuesheng (徐越胜) as

shareholders. Several other individuals with ties to Shanghai have been

involved in the company, but their backgrounds are unclear. A.P. Plaza

Investments Limited Annual Return, Hong Kong Companies Registry, 24 September

2014; ‘三亚南山普门旅游发展有限公司’,

QCC, no date.

5. Nick McKenzie,

Power and Influence: The hard edge of China’s soft power [documentary], Four

Corners, ABC, 5 June 2017,

web.archive.org/web/20170927035228/https://www.abc.net.au/4corners/power-and-influence-promo/8579844.

6. Chris Uhlmann,

‘Top-secret report uncovers high-level Chinese interference in Australian

politics’, Nine News, 28 May 2018; Malcolm Turnbull, ‘Speech introducing the

National Security Legislation Amendment (Espionage and Foreign Interference) Bill

2017’, Malcolm Turnbull [website], 7 December 2017.

7. Peter Hartcher,

‘Huawei? No way! Why Australia banned the world’s biggest telecoms firm’,

Sydney Morning Herald, 21 May 2021,

web.archive.org/web/20210521020450/https://www.smh.com.au/national/huawei-no-way-why-australia-banned-the-world-s-biggest-telecoms-firm-20210503-p57oc9.html.

8. John Garnaut,

‘Engineers of the soul: What Australians need to know about ideology in Xi

Jinping’s China’ [speech transcript], Asian Strategic and Economic Seminar Series,

August 2017, via Sinocism, 17 January 2019.

9. Kirsty Needham,

‘Australia says Yang Hengjun under “arbitrary detention” in China after

espionage verdict postponed’, Reuters, 28 May 2021.

10. John Garnaut, ‘Australia’s China reset’, Monthly,

August 2018,

web.archive.org/web/20180807180411/https://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2018/august/1533045600/

john-garnaut/australia-s-china-reset.

11. John Garnaut,

‘Australia’s China reset’.

12. Peter Martin, ‘CIA

zeros in on Beijing by creating China-focused mission center’, Bloomberg, 7

October 2021; Peter Martin, Jennifer Jacobs & Nick Wadhams, ‘China is

evading US spies – and the White House is worried’, Bloomberg, 10 November

2021. See also Zachary Dorfman, ‘China used stolen data to expose CIA

operatives in Africa and Europe’, Foreign Policy, 21 December 2020,

web.archive.org/web/20201221112115/https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/12/21/china-stolen-us-data-exposed-cia-operatives-spy-networks/.

13. See US Attorney’s

Office ‘Former CIA officer arrested and charged with espionage’, US Department

of Justice, 17 August 2020.

14. David Wise, Tiger

Trap: America’s secret spy war with China, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston,

2011, p. 88.

15. Office of Public

Affairs ‘New York City Police Department officer charged with acting as an

illegal agent of the People’s Republic of China’, US Department of Justice, 21

September 2020.

16. US Attorney’s

Office, ‘Former CIA officer arrested and charged with espionage’; Office of

Public Affairs, ‘Two Chinese hackers associated with the Ministry of State

Security charged with global computer intrusion campaigns targeting

intellectual property and confidential business information’, US Department of

Justice, 20 December 2018; Office of Public Affairs, ‘US charges three Chinese

hackers who work at internet security firm for hacking three corporations for

commercial advantage’, US Department of Justice, 27 November 2017; see also

National Security Division, ‘Information about the Department of Justice’s

China Initiative and a compilation of China-related prosecutions since 2018’,

US Department of Justice, 14 June 2021.

17. Zolan

Kanno-Youngs & David E. Sanger, ‘US accuses China of hacking Microsoft’, 19

July 2021. This came after an earlier coordinated attribution of cyber attacks

to the Chinese government: Marise Payne, ‘Attribution of Chinese cyber-enabled

commercial intellectual property theft’, Minister for Foreign Affairs, 21

December 2018.

18. Daniel Hurst,

‘China “propped the doors open” for criminals in Microsoft hack, Australian spy

agency boss says’, Guardian, 29 July 20.

19. In Australia,

these include Liu Haha, Huang Xiangmo, and Chinese academics Chen Hong and Li

Jianjun. Sean Rubinsztein-Dunlop & Echo Hui, ‘Liberal Party donor Huifeng

“Haha” Liu “engaged in acts of foreign interference”: ASIO’, ABC News, 12 March

2021; Byron Kaye, ‘Australia revokes visas of two Chinese scholars’, Reuters, 9

September 2020; Su-Lin Tan, Angus Grigg & Andrew

Tillett, ‘Huang Xiangmo told Australian residency was cancelled after moving to

Hong Kong’, Australian Financial Review, 6 February 2019.

20. Dan Sabbagh &

Patrick Wintour, ‘UK quietly expelled Chinese spies who posed as journalists’,

Guardian, 5 February 2021.

21. Laura Hughes

& Helen Warrell, ‘MI5 warns UK MPs against “political interference” by

Chinese agent’, Financial Times, 14 January 20.

22. ‘Germany charges

man with spying for China’, Deutsche Welle, no date.

23. Yuichi Sakaguchi,

‘Japan lashes out against alleged Chinese military cyberattacks’, Nikkei Asia,

16 May 2021; Yusuke Takeuchi, ‘Japan to establish intel unit to counter

economic espionage’, Nikkei Asia, 27 August 2020; Tomohiro Osaki, ‘Japan boosts

checks on Chinese students amid fears of campus spying’, Japan Times, 15 October

2020.

24. ‘Court sentences

Estonian marine scientist to prison for spying for China’, ERR, 19 March

2021.

25. 林俊宏

& 劉榮, ‘與共諜組織多次餐敘 前國防部副部長張哲平遭國安調查’, Mirror Media, 27 July 2021; Thomas Grove, ‘A spy

case exposes China’s power play in Central Asia’, Wall Street Journal, 10 July

2019; ‘Nepali security authorities identify a Chinese intelligence agency

official involved in anti-MCC propaganda’, Khabarhub,

12 November 2021; Ezzatullah Mehrdad, ‘Did China

build a spy network in Kabul?’, Diplomat, 17 February 2021; Lynne O’Donnell,

‘Afghanistan wanted Chinese mining investment. It got a Chinese spy ring

instead.’, Foreign Policy, 27 January 2021; Richard C. Paddock, ‘Singapore

orders expulsion of American academic’, New York Times, 5 August 2017; Barbara Moens, ‘Belgium probes top EU think-tanker for links to

China’, Politico, 18 September 2020; Alicja Ptak & Justyna Pawlak, ‘Polish trial begins in

Huawei-linked China espionage case’, Reuters, 1 June 2021; Gillian Bonnett, ‘Couple denied NZ residence due to Chinese

intelligence links’, Stuff, 30 October 2021; Nayanima

Basu, ‘Sri Lanka ex-military intelligence head a

“Chinese spy” who was “blocking” bombings probe’, Print, 6 May 2019; ‘Deux anciens espions condamnés à 8 et 12 ans de prison pour trahison au profit

de la Chine’, Le Parisien, 10 July 2020.

26. A significant and

recent exception is the US’s indictment of five individuals accused of

repressing or spying on dissidents in New York. US Attorney’s Office ‘Five

individuals charged variously with stalking, harassing, and spying on US

residents on behalf of the PRC secret police’, US Department of Justice, 16

March 2022.

27. Rory Medcalf (ed.), ‘Chinese money and Australia’s security,

National Security College, Australian National University, March 2017.

28. Stephen Dziedzic, ‘Australia-China extradition treaty pulled by

Federal Government after backbench rebellion’, ABC News, 27 March 2017.

29. Nick McKenzie,

Power and Influence: The hard edge of China’s soft power [documentary], Four

Corners, ABC, 5 June 2017.

30. Chris Uhlmann,

‘Top-secret report uncovers high-level Chinese interference in Australian

politics, Nine News, 28 May 2018; Malcolm Turnbull, ‘Speech introducing the

National Security Legislation Amendment (Espionage and Foreign Interference)

Bill 2017’, Malcolm Turnbull, 7 December 2017.

31. Peter Hartcher, ‘Huawei? No way! Why Australia banned the world’s

biggest telecoms firm’, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 May 2021.

32. John Garnaut,

‘Engineers of the soul: What Australians need to know about ideology in Xi

Jinping’s China’ [speech transcript], Asian Strategic and Economic Seminar

Series, August 2017, via Sinocism, 17 January 2019.

33. Kirsty Needham,

‘Australia says Yang Hengjun under “arbitrary

detention” in China after espionage verdict postponed,’ Reuters, 28 May 2021.

34. Peter Martin,

‘CIA zeros in on Beijing by creating China-focused mission center’, Bloomberg,

7 October 2021; Peter Martin, Jennifer Jacobs & Nick Wadhams,

‘China is evading US spies – and the White House is worried’, Bloomberg, 10

November 2021; See also Zachary Dorfman, ‘China used stolen data to expose CIA

operatives in Africa and Europe,’ Foreign Policy, 21 December 2020.

35. See US Attorney’s

Office ‘Former CIA officer arrested and charged with espionage’, US Department

of Justice, 17 August 2020.

36. David Wise, Tiger

Trap: America’s secret spy war with China, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston,

2011, p. 88.

37. Office of Public

Affairs ‘New York City Police Department officer charged with acting as an

illegal agent of the People’s Republic of China’, US Department of Justice, 21

September 2020.

38. US Attorney’s

Office, ‘Former CIA officer, arrested and charged with espionage’; Office of

Public Affairs, ‘Two Chinese hackers associated with the Ministry of State

Security charged with global computer intrusion campaigns targeting

intellectual property and confidential business information, US Department of

Justice, 20 December 2018; Office of Public Affairs, ‘US charges three Chinese

hackers who work at internet security firm for hacking three corporations for

commercial advantage’, US Department of Justice, 27 November 2017; see also

National Security Division, ‘Information about the Department of Justice’s

China Initiative and a compilation of China-related prosecutions since 2018’,

US Department of Justice, 14 June 2021.

39. Zolan Kanno-Youngs & David E.

Sanger, ‘US accuses China of hacking Microsoft’, 19 July 2021. This came after

an earlier coordinated attribution of cyber attacks

to the Chinese government: Marise Payne, ‘Attribution

of Chinese cyber-enabled commercial, intellectual property theft’, Minister for

Foreign Affairs, 21 December 2018.

40. Daniel Hurst,

‘China “propped the doors open” for criminals in Microsoft hack, Australian spy

agency boss says,’ Guardian, 29 July 2021.

41. In Australia,

these include Liu Haha, Huang Xiangmo,

and Chinese academics Chen Hong and Li Jianjun. Sean Rubinsztein-Dunlop & Echo Hui, ‘Liberal Party donor Huifeng “Haha” Liu “engaged in

acts of foreign interference”: ASIO’, ABC News, 12 March 2021; Byron Kaye,

‘Australia revokes visas of two Chinese scholars,’ Reuters, 9 September 2020; Su-Lin Tan, Angus Grigg & Andrew Tillett, ‘Huang Xiangmo told Australian residency was cancelled after

moving to Hong Kong’, Australian Financial Review, 6 February 2019.

42. Dan Sabbagh &

Patrick Wintour, ‘UK quietly expelled Chinese spies who posed as journalists’,

Guardian, 5 February 2021.

43. Laura Hughes

& Helen Warrell, ‘MI5 warns UK MPs against

“political interference” by Chinese agent’, Financial Times, 14 January 2022.

44. ‘Germany

charges man with spying for China,’ Deutsche Welle.

45. Yuichi Sakaguchi, ‘Japan lashes out against alleged Chinese

military cyberattacks,’ Nikkei Asia, 16 May 2021; Yusuke Takeuchi, ‘Japan to

establish intel unit to counter economic espionage,’ Nikkei Asia, 27 August

2020; Tomohiro Osaki, ‘Japan boosts checks on Chinese students amid fears of

campus spying’, Japan Times, 15 October 2020.

46. ‘Court

sentences Estonian marine scientist to prison for spying for China,' ERR,

19 March 2021.

47. Thomas Grove, ‘A

spy case exposes China’s power play in Central Asia,’ Wall Street Journal, 10

July 2019; ‘Nepali security authorities identify a Chinese intelligence agency

official involved in anti-MCC propaganda’, Khabarhub,

12 November 2021, ‘Did China build a spy network in Kabul?’, Diplomat, 17

February 2021; Lynne O’Donnell, ‘Afghanistan wanted Chinese mining investment.

It got a Chinese spy ring instead.’ Foreign Policy, 27 January 2021, Richard C.

Paddock, ‘Singapore orders expulsion of American academic’, New York Times, 5

August 2017; Barbara Moens, ‘Belgium probes top EU

think-tanker for links to China,’ Politico, 18 September 2020; Alicja Ptak & Justyna Pawlak,

‘Polish trial begins in Huawei-linked China espionage case,’ Reuters, 1 June

2021; Gillian Bonnett, ‘Couple denied NZ residence

due to Chinese intelligence links’, Stuff, 30 October 2021; Nayanima

Basu, ‘Sri Lanka ex-military intelligence head a

“Chinese spy” who was “blocking” bombings probe’, Print, 6 May 2019; ‘Deux anciens espions condamnés à 8 et 12 ans de prison

pour trahison au profit de la Chine’, Le Parisien, 10 July 2020.

For updates click hompage here