By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

From Suez Crises

To Kuwait 1991

After WWI ended, as we have seen, the US rapidly

withdrew from the Middle East arena. Hence some have argued that since the fate

of the Ottoman Sultanate was on the table right from the start of the battles,

it was only natural that the British and French would seize control of its treasures

and lay down the foundations for a new regional order. By the time the Suez

crises broke Britain was able to hand over power to the US as a friendly

successor. But neither Eisenhower nor his fervently anti-communist secretary of

state, John Foster Dulles, understood this transition in strictly geopolitical

terms; both believed that the liberating American faith in national

self-determination and consent of the governed would supplant Britain’s

self-aggrandizing colonialism. Both morality and national interest dictated

such a course. As Dulles said in a prime-time televised address in 1953:

"We cannot afford to be distrusted by millions who could be sturdy friends

of freedom."

At the end of WWI the history of the making of the modern Middle East

could be seen as the exercise of imperial power, skilled at advancing its

interests over those of others. Britain however was also a global power with an

interest in the stability provided by a rules-based international system, as

well as a Christian, liberal state, based on the rule of law, whose politicians

and citizens believed in probity, justice, decency and fair play. The potential

for conflict between national interest, enlightened self-interest and ethics

was considerable, most starkly illustrated by the controversies over Suez and

the 2003 Iraq war. Officials had various ways of resolving this dilemma,

including keeping doubtful acts out of the limelight and rationalization. They

did not subscribe to the view of one member of the UN Special Committee on

Palestine in 1947 that ‘One might say that the British are really cursed by

their possession of the world’s largest empire; in their desire to keep it

intact they apply methods which their ethical principles certainly would

prohibit them from using in private dealings.’ 1

Those who blame Britain and France for the endless strife in Palestine,

Lebanon, and Syria have a plausible case in the sense that the age-old imperial

policy of “divide and rule,” applied to an already fractious region, helped to

exacerbate existing tensions between Arabs and Jews, Christians and Muslims,

Sunnis and Shiite Muslims, and so on.

In its imperial heyday, Britain was both self-confident and high-minded.

The world’s leading power had a sense of being in harmony with the progressive

forces of the universe. Having reached the top of the ladder of Progress, men

like Palmerston and Cromer saw their task as being to lead the way and direct

the march of other nations, in particular less favoured

or less civilised ones. 2 Rule over non-Europeans was

regarded well into the twentieth century as part of the natural order of

things. In the case of the Middle East, this approach was tinged by the view of

Islam as a danger to be opposed, as by an assumption that the region was

somehow exempt from normal European moral codes. 3 In 1843 Blackwood’s Magazine

ascribed the occupation of Aden to the habit of ‘taking the previous owner’s

consent for granted, whenever it suited our views to possess ourselves of a

fortress, island or tract of territory belonging to any nation not sufficiently

civilized to have representatives at the Congress of Vienna’. 4

Justifying air control in Iraq to parliament, a minister claimed that

many of the tribesmen loved fighting for fighting’s sake and had no objection

to being killed. According to Priya Satia, Britons in the 1920s regarded the

moral world of Arabia to be distinct from their own, where the use of bombing,

at the time a new feature of warfare, would have been regarded very

differently. 5

At the same time, the empire was also considered to confer obligations.

Its governance was seen as a sacred trust. The men who went out to Egypt after

1882 went not just to exercise British control of the country, but to serve it.

In a draft note of advice for young officials in Egypt, the Oriental Secretary,

Harry Boyle, wrote that, the one and only subject which we should keep in view

approaches pure altruism […] to confer upon a people whose past is one of the

most deplorable ever recorded in history, those benefits and privileges which

they have never enjoyed at the hands of the numerous alien races who have

hitherto held sway over them; and to endeavour to the

utmost of our power to train up, by precept, generations of Egyptians who in

the future may take our place and carry on the tradition of our administration.

6

The Englishman was in Egypt ‘as a guide and friend, not as a master’. 7

Curzon went so far as to argue that Britain should be judged not by its

domestic achievements, but on the marks it left on the people, religions and

morals of the world. 8

Foreigners might raise a skeptical eye at such talk. An Italian remarked

to a British diplomat on ‘a strange dogma in your religion: that the British

empire was conceived without original sin’. 9 But if the policy was a mixture

of self-interest and obligations, the high-minded sentiments dating from the

Victorian era was not simply hypocritical. In Egypt, as in the Aden

Protectorates or Palestine and Iraq under the mandates, there was a genuine

belief that Britain had a responsibility for the promotion of good government

and welfare, and that officials were doing good, rather than simply selfishly

promoting British national interests. As Stephen Longrigg,

who helped set up the Iraq mandate, wrote in 1953, ‘local British officials,

children of their own country and centuries-old standards, did what they could,

with a real devotion in scores of cases, to guide and help and strengthen’. 10

The British could take credit for ending the slave trade in the Persian Gulf

and the corvée system of forced labor in Egypt, along with the creation of

security in hitherto insecure tribal regions. 11

Where practice failed to live up to precept, as was frequently the case

regarding money for development, individual consciences were pricked. Sir

Bernard Reilly, who had a long career in the Aden Protectorates, spoke of his

shame at their neglect. 12 The manner in which the Palestine mandate ended

caused genuine distress. The Colonial Secretary’s report on Palestine of June

1948 deplored the fact that Britain’s ‘task has concluded in circumstances of

tragedy, disintegration, and loss’. 13 This sense of responsibility for the

welfare of people in the Middle East extended beyond the narrow confines of

British sovereign territory, to include the mandates and Egypt under the

‘veiled protectorate’. It also extended to Persia, where the British took an

interest in the fate of various minorities, including the Zoroastrians, Jews,

Assyrians and the large Armenian population of Azerbaijan. 14

The exercise of power in the informal empire was tempered by a series of

unwritten rules and constraints, deriving from a mixture of values, the codes

of conduct which officials had been brought up with, and notions of enlightened

national self-interest. They were certainly not always observed, but disregard

made policy makers uneasy and exposed them to criticism. Perhaps most important

was the belief that commitments should be honored. Diplomacy would be

undermined, and prestige would suffer if Britain was believed not to keep its

word. In the tribal societies of Arabia breaking one’s word was an especially

heinous sin. 15 But it was also a matter of honor. Officials regarded

imputations of bad faith as odious. 16

Their view was not necessarily shared by ministers. At the coronation in

1953, the Ruler of Bahrain buttonholed Churchill to lobby for support in a

dispute with neighboring Qatar. ‘Tell him’, said a very tired Prime Minister,

‘that we try never to desert our friends.’ He then paused. ‘Unless we have to.’

17 (The translator diplomatically omitted the qualification.) The list of those

who felt themselves let down by the British is quite extensive.

Commitments came into question

where circumstances changed, promises had been given to rulers who had little

hold over their territories or lost their influence, and where promises proved

in conflict with each other. Turning down a request for protection by Ibn Sa’ud, the Political Agent in Kuwait declared that ‘the

Great [British] Government does not accord protection rashly or without much

forethought’. 18 That, however – as the conflicting wartime promises to the

Arabs, Zionists, and French, which left officials with a deeply uneasy

conscience, underscored – was not always true. In the early 1920s, the British

found themselves caught between conflicting promises to the Persian government

and the sheik of Mohammerah. Having failed to mediate

between the two, and being unwilling to use force, the British opted to support

the more powerful side. Official consciences, however, were far from easy – one

official spoke of ‘throwing our friends to the wolves’ – and questions were

asked in parliament. 19 A later Political Resident in the Gulf, Sir Bernard

Burrows, describes the Sheikh’s treatment as ‘one of the most disreputable

episodes in British imperial history’. 20

The second cluster of dishonored commitments arose at the end of empire

when British power was in terminal decline. Back in the late 1930s, the Peel

Report had insisted that ‘the spirit of good faith’ forbade abandonment of the

mandate. Britain could not ‘stand aside and let the Jews and Arabs fight their

quarrels out’. 21 A decade later, when this task seemed impossible, it was

abandoned. Aware that they had exposed themselves politically by allying with

the British, the leaders of the South Arabian Federation were uneasy as to how

far they could rely on their ally, despite a succession of assurances from both

Conservative and Labour ministers. 22 Yet in February

1966 the Labour government, which found the Federal

rulers ideologically distasteful, announced that following the withdrawal of

the Aden base there would be no British defense guarantee. The reaction among

Federal ministers was a mixture of anger and dismay. ‘We cannot’, the chairman

of the Federal Council told the junior minister sent out to inform them of the

decision, ‘believe that it is your wish that we shall be sacrificed just

because after many years of repeated promises to the contrary, the British

government finds that it suits its own self-interest, to desert its friends and

leave them in the lurch.’ 23

There was a similar response from former Conservative ministers as well

as British officials, some of whom took the unusual step of forming an action

committee to try to change the government’s mind. 24 The former Colonial

Secretary, Ian Macleod, denounced the breaking of pledges to Gulf rulers in

1967 as ‘shameful and criminal’, 25 while several senior diplomats in the Gulf

wrestled with their consciences over whether they could ‘decently continue to

represent HMG after this double-dealing’. 26

Closely related to the belief that commitments should be honored was a

concern to act honestly and honorably. Britain should not deceive, lie and

deliberately mislead, or otherwise, act in a manner to impair its good name.

Again, this was a precept often honored in the breach. The most famous instance

is the discomfort of British officers involved in the Arab Revolt, on learning

of the provisions of the Sykes– Picot agreement. The Arab Revolt, Lawrence

wrote in Seven Pillars of Wisdom;

had begun on false pretenses […] In the East persons were more trusted

than institutions. So the Arabs, having tested my friendliness and sincerity

under fire, asked me, as a free agent, to endorse the promises of the British

government. I had no previous or inner knowledge of the McMahon pledges and the

Sykes– Picot treaty […] But, not being a perfect fool, I could see that if we

won the war the promises to the Arabs were dead paper. Had I been an honorable

adviser I would have sent my men home, and not let them risk their lives for

such stuff. Yet the Arab inspiration was our main tool in winning the Eastern

war. So I assured them that England kept her word in letter and spirit. In this

comfort they performed their fine things: but, of course, instead of being

proud of what we did together, I was continually and bitterly ashamed. 27

Similar unease was expressed by other senior British officers with the

Arab Revolt, as well as later by officials in Palestine. One High Commissioner,

Sir John Chancellor, wrote privately that the Arabs had been treated

‘infamously […] That destroys the moral basis on which the Government must

stand if one is to do one’s duty with confidence and conviction.’ 28 At the

Colonial Office Sir John Shuckburgh spoke of ‘a sense of personal degradation’

at the way Zionists and Arabs were being told two different things. 29 As for the

Suez crisis, Sir Frank Cooper, then head of the Air Ministry’s Air

Secretariat, later described ‘the shame of Suez’ being in the way it was

handled by Eden and Selwyn Lloyd, who did it ‘in such a hole-in-the-corner

way’. 30 The air commander of the operation, Air Chief Marshall Sir Denis

Barnett, accidentally found out about the plot. ‘I couldn’t believe that it

could be so. I didn’t think that we would behave like that.’ 31 This aspect of

the affair caused much less concern in the French military. 32

It has been suggested that when the French and especially the British

prime minister, Anthony Eden, started to lose their head, Eisenhower kept his.

However, the Eisenhower administration relied on the advice of officials

who admired Nasser as a nationalist and anti-Communist: a secular modernizer,

the long hoped-for “Arab Ataturk.” The most important and forceful of the

Nasser admirers was Kermit Roosevelt, the C.I.A. officer who had done so much

in 1953 to restore to power in Iran that other secular modernizer, Shah

Mohammed Reza Pahlavi.

To befriend Nasser, the Eisenhower administration suggested a big

increase in economic and military aid; pressed Israel to surrender much of the

Negev to Egypt and Jordan; supported Nasser’s demand that the British military

vacate the canal zone; and clandestinely provided Nasser with much of the

equipment, and many of the technical experts, who built his radio station Voice

of the Arabs into the most influential propaganda network in the Arab-speaking

world. Yet each of these overtures produced only grief, as Eisenhower himself

soon came to learn.

Offers of aid were leveraged by Nasser to extract better terms from the

Soviet Union, his preferred military partner. Pressure on Israel did not

impress Nasser, who wanted a permanent crisis he could exploit to mobilize Arab

opinion behind him. Forcing Britain out of the canal zone in the mid-50s

enabled Nasser to grab the canal itself in 1956. Rather than use his radio

network to warn Arabs against Communism, Nasser employed it to inflame Arab

opinion against the West’s most reliable regional allies, the Hashemite

monarchies, helping to topple Iraq’s regime in 1958 and very nearly finishing

off Jordan’s.

Bluntly put: Nasser had duped

Eisenhower.

Thus Eisenhower’s gamble was based on a delusion. Nasser was not an

Egyptian George Washington or Moses, determined to lead his people out of

colonial bondage and into a proud independence. Nasser was an empire

builder who saw America’s Arab allies, Jordan, Iraq and Lebanon, as

dominoes to be knocked over on his path to regional hegemony. At the same time

that Washington was propping up Iraq’s King Faisaland

Jordan’s King Hussein, Nasser was dispatching his agents to torpedo their rule.

(He succeeded in Iraq and failed in Jordan.)

Issues which raised ethical

objections

Disposing of other people’s territory was frowned upon. The 1907

division of Persia into spheres of British and Russian influence was greeted by

a chorus of disapproval from radicals and Labour MPs.

33 Harold Dickson, who was Political Agent in Kuwait, considered that the 1922 Uqair settlement in which Kuwait lost two-thirds of its

territory to compensate Ibn Sa’ud for concessions to

Iraq ‘savoured of surrender pure and simple of a

strong state to a weak state’. Sir Percy Cox ‘grievously harmed a great reputation

for fair dealing’. 34

Other issues which raised ethical objections include the sequestration

of Jewish property as part of the Palestine counter-terrorism campaign in the

1940s, and a proposed response to an Israeli demand for a ‘partnership’ as the

price of British overflights to Jordan in 1958. 35 A senior Foreign Office

official objected: I confess I do not much like the idea of sucking up to the

Israelis now when we need them and dropping them as soon as this need is over.

It seems to me highly dishonest, and also liable to destroy any lingering trace

of respect or confidence in us that the Israelis may retain. 36

1948-1949:

Israel Declares Independence After the British Give up Control of Palestine

Several years earlier, when Kuwaiti sterling reserves were under

discussion, another official had warned that using ‘our influence in Kuwait

towards a solution of this problem which is intended to help the UK rather than

Kuwait would be dubious ethics’. 37

Arms sales became ethically sensitive with the dramatic growth of Middle

East defense markets in the 1970s. Sales to the most unsavory regimes were

ruled out, but the restrictions were insufficient to prevent controversy.

According to Sir Anthony Parsons, by then in retirement, the Middle East arms

race encouraged conflict, aggravated already grisly human rights behavior and

multiplied the human cost of war. The Liberal leader, David Steel, described

the sight of the developed nations pouring weapons into the Middle East and

then collectively wringing their hands when they were used as ‘appallingly

hypocritical’. 38

A legal sanction was also vital to Blair to prevent a significant number

of ministerial resignations and a mass revolt by MPs. 39 The key question was

whether, in the absence of a second UN resolution explicitly authorizing the

use of force, Security Council Resolution 1441, passed in autumn 2002, would

provide an adequate legal justification. Until early February 2003 the Attorney

General, Sir Peter Goldsmith, had argued the need for a new resolution. On 7

March, with the prospects for this looking increasingly unlikely, Sir Peter

stated that while a second resolution would still be the safest legal course, a

reasonable case could be made for going ahead without it, adding, however, that

were the matter ever to come to court, that court might disagree.

Once it was clear that there would be no second UN resolution, Sir Peter

was asked for a straight yes or no ruling. He then determined that military

action would be legal provided the government certified that Iraq was in

‘further material breach’ of UN resolutions. His view was not shared by the

senior Foreign Office Legal Advisers, the former Lord Chief Justice, Lord

Bingham, or the UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan. 40 Under the 2007 Ministerial

Code, ministers were obliged ‘to comply with the law including international

law and treaty obligations’. The Conservative government was keen to stress the

legality of operations against Libya in 2011 and ISIS in 2014. 41

There was a fourth set of ethical constraints on informal empire. While

the British could indeed be ruthless, there were limits as to how far it was

regarded as acceptable to go. A character in Naguib Mahfouz’s novel, Sugar

Street, describes British imperialism as ‘tempered perhaps by some humane

principles’. 42 The brutality which marked French policy in Algeria,

particularly in its early and final stages, is largely absent. Nor is there any

British equivalent of either the French shelling of Damascus in 1926 and 1945

or the extensive use of torture in the Algerian civil war.

But there were a series of instances involving what could

euphemistically be described as excesses. Some of these were spontaneous, a

matter of bored, frightened or angry troops or police running amok. But in

Palestine in the late 1930s, the smashing up of property, looting and violence

appear to have had tacit support from the military authorities, who saw them as

a means of frightening the rebellious population into submission. There

certainly appear to have been hardly any successful prosecutions of servicemen

on such charges. 43 In other cases the brutality was deliberate. In Palestine,

as later in Aden in the 1960s, torture was used to gain information. According

to the High Commissioner, Sir Reginald Turnbull, without so-called ‘effective

interrogation,’ the authorities would have no forewarning of terrorism. 44 Some

soldiers were sufficiently uneasy about these practices to refuse to hand over

prisoners to the Intelligence Corps. 45 There was frequent recourse in

Palestine to collective punishment. In the largest such instance, which

occurred in Jaffa in 1936, troops blew up between 220 and 240 houses, leaving

some 6,000 Palestinians destitute. 46 Such actions, which served to fracture

and impoverish the Palestinian population, were, however, within the letter of

the law and emergency regulations in force in Palestine. 47 The same was not

true of the final phase of the Aden insurgency when the Argyll and Sutherland

Highlanders acted with considerable brutality. One soldier reported that

instead of shouting Waqaf (halt) three times as

prescribed under the stop and search procedures, British troops shouted ‘Corned

Beef’ and then instantly gunned civilians down. 48 The 2003 invasion led to a

significant number of Iraqi claims for mistreatment and unlawful detention.

Where such actions became public, there was a protest. The excesses of

the battle of Omdurman in 1898, when Ansar wounded were killed, the Mahdi’stomb destroyed and his body thrown into the Nile,

led to parliamentary questions and the publication of a White Paper to try to quieten public opinion. 49 The

military’s behavior in Palestine in the 1930s drew protests from within the

Palestine administration, and also from the Anglican clergy. Bishop George

Graham-Brown was particularly vocal, at one point describing military and

police action as ‘terrorism for which the Government is morally responsible’.

50 The 1906 Dinshawi incident generated strong

criticism in Britain.

On other occasions, ministers and officials prevented what they regarded

as excesses. When Allenby demanded an indemnity following the assassination of

the Sirdar and Governor-General of Egypt, Sir Lee Stack, in 1924, London

objected that ‘the appearance of a vindictive penalty’ was not in the British

tradition. 51 In 1940 Wavell rejected contingency plans which had been drawn up

for a scorched-earth policy in Egypt, saying he refused to be responsible for a

famine in the country. 52 Both the First Sea Lord, Lord Mountbatten, and the

First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Hailsham, expressed

deep unease over early plans for the Suez operation which would have involved

naval bombardments liable to cause civilian casualties. 53 Air policing in Iraq

was subjected to parliamentary criticism, primarily on the grounds that it was

indiscriminate, and that women and children were attacked.54 In 1924 the Labour Colonial Secretary felt it necessary to present a

defense to parliament which stressed that destruction was neither the aim nor

normal result of air action. But since no independent observers were present,

most of the destructive impact of air policing could be concealed by editing

out details and the use of euphemisms. 55

Assassination seems generally to have been ruled out. The Foreign Office

was horrified when Sir Percy Cox suggested the assassination of Wilhelm Wassmuss, a highly successful German agent operating in

Persia during World War I. The idea was described as repugnant and reference to

the subject was ordered to be deleted from despatches.

56 The rejection of proposals to assassinate the Mufti during World War II and

Egyptian intelligence officers in Yemen in the 1960s, however, reflected the

view that these were liable to be counter-productive, rather than ethical

considerations. 57 Nasser’s assassination was considered in 1956 but ruled out

as much for practical as ethical reasons. 58 The 1957 Anglo-American plan for

overthrowing the Syrian government included the ‘elimination’ of three Syrian

figures. 59 According to press reports, active consideration was on several

occasions give to the deposition or assassination of Colonel Qadaffi, while British, along with American, French and

Israeli officials, discussed the assassination of Saddam Hussein in the run-up

to the 1991 Gulf war. 60

If there was broad agreement as to what, ideally at least, Britain

should not do, what, over and above the promotion of good government, did the

British feel morally obliged to try and do? There were two schools of thought

as to how far Britain was obliged to try to promote its values in the Middle

East. On the one hand was the view that representative institutions did not

represent a panacea for all the troubles of Eastern countries, 61 and that, in

Curzon’s words, ‘the ways of Orientals are not our ways, nor their thoughts our

thoughts. Often when we think them backward and stupid, they think us

meddlesome and absurd.’ 62 In the summer of 1957, the ambassador to Jordan, Sir

Charles Johnston, commented that while it was disappointing that a country

built up under British traditions should have resorted to a ‘special brand of

paternal authoritarianism’, nevertheless ‘taking facts, and Arabs as we find

them’, British interests were better served by maintenance of stability and the

Western connection than ‘an untrammelled democracy

rushing downhill towards communism and chaos’. 63

To an Arab critic like Rashid Khalidi, such attitudes smacked of ‘the

casual, borderline racist cynicism of Westerners who saw Arab politics as

inevitably authoritarian and corrupt’. 64 In a speech in Kuwait in 2011 during

the ‘Arab Spring’, David Cameron expressed regret for Britain’s role in

sustaining Middle East strongmen in the mistaken belief that they maintained

stability. 65 This was in line with an alternative body of opinion, going back

to the nineteenth century, that Britain had a responsibility to support liberal

democracy. Hence criticism of the way Britain had throttled democracy in Egypt

in 1882 and pressure on the government to support the Persian constitutional

movement in the early 1900s. 66 Overall, however, short-term political objectives

tended to outweigh concern for the promotion of values.

The promotion of human rights first came to the fore during David Owen’s

period as Foreign Secretary in the late 1970s, and again in 1997, when the new Labour Foreign Secretary, Robin Cook, stressed the need for

an ethical dimension to British foreign policy. The Middle East presented

Britain with a particular dilemma. Authoritarianism was prevalent across the

region, including the Gulf, where, as the case of the Shah had first shown,

there was an inevitable reluctance to press friends and customers too hard on

what they regarded as purely domestic affairs. A 2006 House of Commons Foreign

Affairs Committee report described the human rights situation in Saudi Arabia

as being the cause of grave concern, while also noting that Britain’s

relationship with the Kingdom was of ‘critical and strategic importance’.

Britain promoted a quiet dialogue between Human Rights Watch and the Saudi

authorities and worked to improve the human rights situation in Bahrain

following the ‘Arab Spring’ In the later Mubarak years, British government

agencies supported projects in Egypt intended to promote a credible electoral

process, human rights, and free media.

In the Mideast, borders have always been drawn in blood, it is happening

once more today.

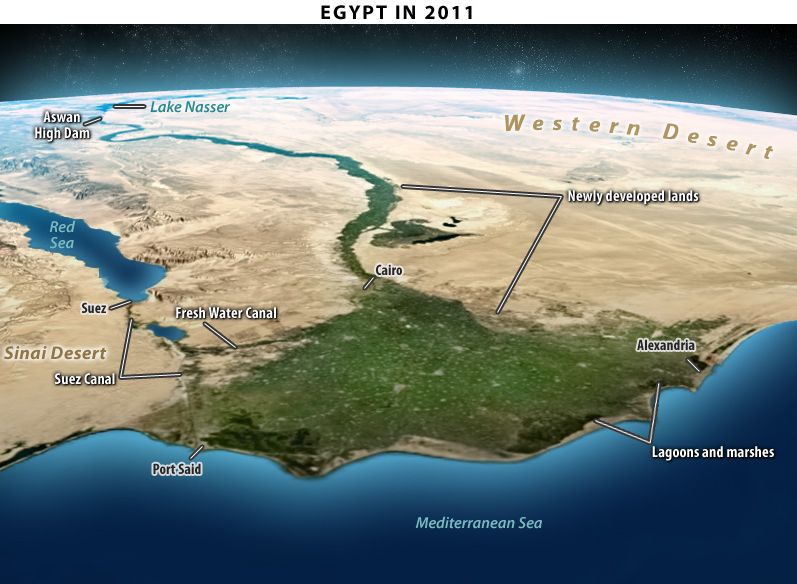

The map below illustrates the distribution of youths under 25 years old

and the gross domestic product per person in each Arab country:

Several decades after British influence during the US President

Eisenhower years was replaced with that

of the US, the above mentioned 'Arab Spring' erupted in Tunisia on December 17,

2010, when a policewoman confiscated the vegetable cart of a 26-year-old street

vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, in SidiBuzid, 300 km south

of Tunis. Bouazizi appealed to the provincial headquarters in Sidi Buzid, where his case was rejected. A few hours later

Bouazizi doused himself with flammable liquid and set himself on fire. This

incident sparked a revolution in Tunisia and other Arab countries.

Demonstrations and riots ignited throughout the country, and police and

security forces took serious measures against the protesters. Images of

protests and brutal police action were featured on, and circulated through

social media (i.e., Facebook and YouTube). The popular slogans of the

demonstration across the country were "Jobs for all," "Down with

the bribes and favoritism," "Tunisia free" and "Ben Ali get

lost." To restrain the rage of the youth protesters, and to maintain

security and order in the country, President Ben Ali promised he would create

300,000 jobs in the next 2 years, albeit ironically shortly thereafter issuing

a decision to close down schools and universities and branding the protesters

as “terrorists.’’ This self-contradicting message provoked the protesters and

drove them to further confrontations with the police and security forces. Under

this snowballing pressure, Ben Ali fired part of his ministerial cabinet, called

for early parliamentary elections within six months, and promised the

protesters that he would step down by the end of his presidential term in 2014.

These promises did not calm down the protestors, who instead targeted replacing

the incumbent regime with a democratic one. When Ben Ali realized that he had

no more choices, he fled to Saudi Arabia along, with his family on January 14,

2011, marking the end of his 24 years of authoritarian rule in Tunisia.

Against this backdrop, Bouazizi was portrayed as a champion who had

galvanized the frustrations of the region's youth against their dictatorial

regimes into mass demonstrations, revolt, and revolution, all of which became

known collectively as the “Arab Spring.” On January 25, 2011, Egyptian

activists protested against the poverty, unemployment, and corruption

perpetrated by Mubarak's regime and his closest allies.

The key movements that led protests include the following: 1) Kefaya is the unofficial name of the Egyptian Movement for

Change and was established in 2004 with the objective of changing the political

situation in Egypt. It gained wide support at the grassroots level when it

criticized the 2005 constitutional referendum and presidential election

campaigns. It also protested against the re-election of Hosni Mubarak in 2010

and the idea of transferring power to his son, Gamal. It was one of the key

groups and movements that contributed to the success of the 25 January

Revolution; 2) The National Association for Change, a loose political

association that consists of activists from different sectors of Egyptian

society. It was founded in 2010 with the objective of changing the political

setting in Egypt via democracy, social justice, and free elections. It played a

significant role in the protests of 2011 that ended the rule of Hosni Mubarak;

3) The 9 March Group for the Independence of Egypt's Universitieswas

founded in 2003. It took its name from March 9, 1932, when Lotfiel-Sayed,

the first president of Cairo University, resigned in protest against the

ministerial decision to fire Taha Hussien from the deanship of the Faculty of

Arts. The group's primary objective was to assure the independence of Egyptian

universities from security and government interference. It played a key role in

the 2011 protests that led to the resignation of Hosni Mubarak; and 4) The

April 6 Youth Movement, an Egyptian activist group established in 2008 to

support workers in El-Mahalla El-Kubra, an industrial town, who were planning

to strike on April 6. The founders of April 6 … used social media (i.e.,

Facebook, Twitter, Flickr) to disseminate the workers’ demands and grievances

and to mobilize the public to support their strike. Khaled Mohamed Saeedwas a young Egyptian man who died under disputed

circumstances in Alexandria on June 6, 2010, after being arrested and beaten by

Egyptian security forces. Images of his disfigured corpse were circulated via

the Internet and smart phones, scandalizing Egyptian security forces and

motivating the anger of the public against Mubarak's regime. A prominent Face

Group was founded under his name (“We are all Khaled Said”) and moderated by

Wael Ghonim, a distinguished figure in the Egyptian Revolution of 2011.

The protesters urged Mubarak to step down in favor of an elected

democratic government that would address their demands. A day later the

government banned all public gatherings and security forces dispersed a number

of peaceful demonstrations. A curfew was set up, and all forms of communication

were blocked. Revolts spread from the Liberation Square (Midan

al-Tahrir) in Cairo to other squares in the country, calling for the departure

of Mubarak and his undemocratic regime. The immediate reaction of the president

was to dissolve his cabinet and form a new one chaired by Ahmed Shafik, the

former Air Force Chief. He also appointed Omar Sulaiman, Egypt's intelligence

chief, as vice president and delegated him to begin negotiations with the key

figures of political parties (Mubarak's speech. On February 4, 2011, thousands

of protesters gathered at Tahrir Square in Cairo and other principal cities of

Egypt, calling for Mubarak's departure and regime change. No choice was left

for President Mubarak except to leave his office before completing his

presidential term in 2013. Under the mounting pressure of the protests, and in

the face of external appeals for democratization, he stepped down on February

11, 2011, leaving the administration of the country to a military council

headed by Mohamed Hussein Tantawi and a team of senior military officers.

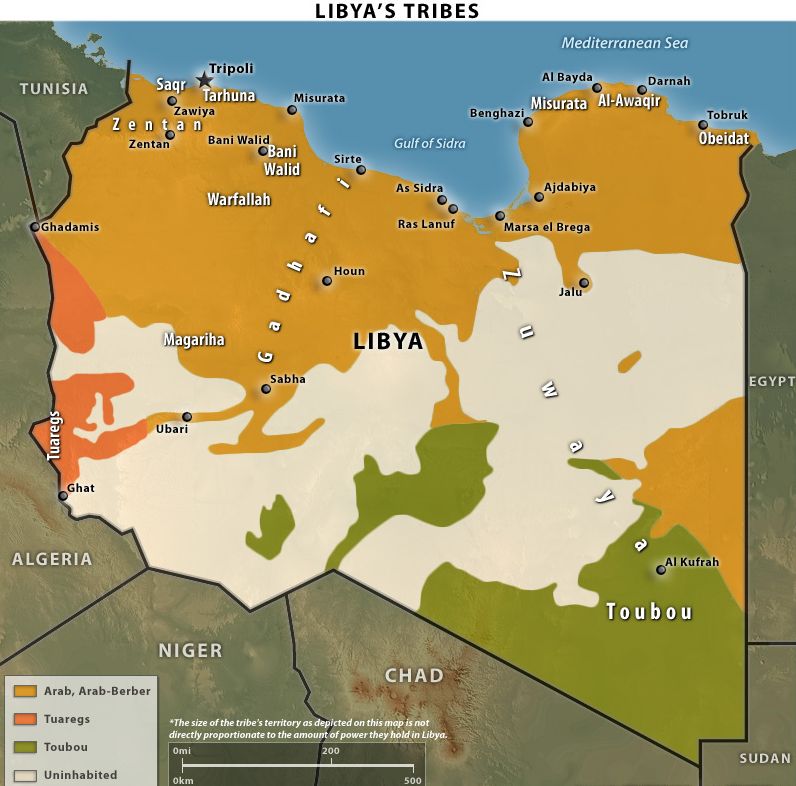

The snowballing of the Arab Spring forced Libyan dictator Muammar

al-Gaddafi to take preventative measures, including the reduction of food

prices, the dismissal of military officer defectors, and the release of several

Islamist prisoners. However, these preventative measures seem not to have been

effective because, on February 17, 2011, major protests erupted in Benghazi

against al-Gaddafi's dictatorial regime. The growing dissatisfaction of the

protesters was correlated with the corruption of al-Gaddafi's regime,

deep-rooted systems of patronage, and widespread unemployment among the Libyan

youth. In his first media appearance, al-Gaddafi accused the protestors of

being “drugged” and cooperating with al-Qaeda in the region. As a result, he

rejected their demands for regime change and proclaimed that he would prefer to

die a martyr rather than leave Libya for the “drugged” and mercenaries of the

West (al-Gaddafi's speech, 2011). The complexity of this situation led some

diplomats at Libya's mission to the United Nations in New York to side with the

revolt and urge the Libyan army to support the protesters. By the end of

February 2011, al-Gaddafi lost control of key cities of Libya, and the military

confrontation between his loyalists and revolutionary forces gradually

escalated into a full-scale civil war. The UN Security Council and EU

governments imposed sanctions on al-Gaddafi and his family, and suspended

Libya's membership in the UN. On March 17, 2011, the UN Security Council

imposed a no-fly zone in the country's airspace and announced that “all

necessary measures” should be taken to protect civilians against al-Gaddafi's

forces (Security Council. Supported by NATO air forces, the Libyan National

Council in Benghazi declared itself the legitimate representative of the Libyan

people. The declaration was recognized by Western and Arab countries that

denounced the legitimacy of al-Gaddafi to lead his own nation. The military

confrontation continued between the two parties for a couple of months until

the forces of the revolutionaries entered Tripoli in the last week of August

2011, and al-Gaddafi and his forces left the city, taking their final refuge in

Bani Walid, Sirte, and other cities. After the liberation of Tripoli, fighting

continued for about two months until Colonel al-Gaddafi was captured on October

20, 2011, and killed in the city of Sirte. His death marked the end of his

42-year rule, and 3 days later the Libyan National Council declared the

liberation of the country and started the process of drafting a new

constitution and electing a new government.

The events of Tunisia and Egypt also inspired prodemocratic reformers in

Yemen to continue their struggle against the leadership of Ali Abdullah Saleh,

who came to power in 1990. To curtail the political situation in Yemen, Saleh

announced that he would neither run for the future presidential election in

2013 nor hand power over to his son, Ahmad.

Opposition party leaders and political activists did not buy these

promises and continued their pressure on Saleh to step down in favor of early

presidential and parliamentary elections. In response, Saleh fired his entire

cabinet and promised protestors a number of further reforms and regime change.

During this stressful period, the Yemeni ambassador to the United Nations in

New York resigned from his office and condemned the suppression of peaceful

demonstrators by the regime's security forces. Several top military commanders

defected, and Yemen's ambassador to Syria quit his post and joined the

antigovernment movement that called for Saleh's resignation. When the situation

became very complex and out of control in Yemen, the Gulf Cooperation Council

countries mediated between the two disputing parties and submitted a proposal

for a smooth transfer of power. The government arrogantly rejected the

proposal. On June 7, 2011, Saleh was seriously injured in a rocket attack on

Yemen's presidential compound in Sana'a and was flown to Saudi Arabia, where he

received medical treatment. The administration of the country was entrusted to

his deputy, Abdrabuh Mansur Hadi. While Saleh was

receiving medical treatment in Saudi Arabia, protestors formed a transition

council on August 18, 2011, to pave the way for a power transfer. Under

mounting internal and external pressure, Saleh signed the Gulf-brokered accord

on November 22, 2011, and agreed to hand over power to Abdrabuh

Mansur Hadi, on the condition that he would be given immunity from prosecution.

Hadi was then expected to form a national unity government and call for early

presidential elections within 90 days. By signing the Gulf-brokered accord,

Saleh ended his 33 years of authoritarian rule, albeit with the proviso that he

would retain his title and certain privileges until the new presidential

elections took place in February, 2012.

Apart from these four Arab countries, anti government

demonstrations and demands for regime change spread to Bahrain, Algeria, and

Syria. The protestors in Bahrain and Algeria were suppressed by security and

police forces, while in Syria, military confrontation escalated into civil war

between die-hard supporters of al-Assad's regime and their political opponents,

a conflict that still rages to date.

During the First World War Britain seized the territory from Turkey in

1918, yet turned it over to France in 1920 but took it back from Vichy in 1942.

Following nominal independence in 1946, Syria became a theater of Cold War

rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union. The stream of military

coups between 1949 and 1970 concluded with the Hafez al-Assad putsch that left

Syria in the Kremlin camp. Assad, however, proved anything but subservient to

his superpower benefactor. The struggle for Syria continued in desultory

fashion as Syria irritated Moscow by flirting with the U.S. in Lebanon and

sending troops to support the American reconquista of

Kuwait in 1991. The U.S. soon reverted to form, labeling Syria a “terrorist

state” and condemning both its support for Hezbollah in Lebanon and its

alliance with Iran. In 2011, the struggle became a war. The U.S. and Russia, as

well as localhegemons, backed opposite sides,

ensuring a balance of terror that has devastated the country and defies

resolution.

The Russians, having lost Aden, Egypt, and Libya years earlier, backed

their only client regime in the Arab world when it came under threat. The U.S.

gave rhetorical and logistical support to rebels, raising false hopes, as it

had done among the Hungarian patriots it left in the lurch in 1956, that it

would intervene with force to help them. Regional allies, namely Saudi Arabia,

Qatar, and Turkey, were left to dispatch arms, money, and men, while

disagreeing on objectives and strategy.

By mid-2012, the opposition was divided into no fewer than 3,250 armed

companies. All attempts at unifying them failed, in part because local warlords

sought loot rather than national victory and the outsiders refused to

coordinate their policies. The traditional invaders of the Mideast, Britain,

France, and the U.S., became prisoners of their own rhetoric. Whereas Saudi

Arabia, overestimated the rebels’ strength while underestimating Assad’s.

As I pointed out in August 2016, whenever next Assad’s back

is against the wall, Russia and Iran pitch in with more help. When the rebels retreat,

Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey send more fighters and weapons. And, where

foreign interventions were intended to end the war have instead entrenched it

in a stalemate in which violence is self-reinforcing and the normal avenues for

peace remain closed.

Conclusion

Those who defended the postwar order say that no division or partition

had taken place because the entities of Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Turkey -

and perhaps also to a lesser extent Palestine, Lebanon and Jordan - were based

on an old geopolitical legacies. Their transformation into states, goes this

line of argument, was accomplished through close cooperation among the elites

and dignitaries of their cities. On top of that, they claim, foreigners soon

left and these countries enjoyed independence with their fate in the hands of

their own people.

However, the issue that should not be ignored is that the new regional

order was created in isolation from the will of those living in the sultanate.

People who lived throughout their history in the shade of imperial order

suddenly found themselves squeezed within the borders of a national sovereign

state, built upon foundations that were never clear. Why, for example, were

tribes, clans and families divided between Iraq and Syria or between Syria and

Jordan or between the southern Palestine and Sinai or between northern

Palestine and Lebanon? Why were Arabs given more than one state? The Turks were

given their state, but why weren't the Kurds allowed to establish their own? In

most of the new states, and in Turkey, Iraq and Syria in particular, the elites

who took over did not know how to deal with the ethnic, religious and sectarian

pluralism that had flourished and resorted to using armed force.

Today, the region is witnessing a multi-level, multi-dimensional

explosion, one that reflects the inability of the first postwar regional order

to survive and continue. In the small triangular spot squeezed between southern

Turkey, northern Iraq and Syria alone is an example of the extremely

complicated overlap of regional and sub-regional conflicts not only among the

states but also among sub-state entities and international powers trying to

maintain their influence in the region. In the aftermath of the Arab uprisings,

Syria is no longer able to behave as a fully sovereign state or to impose its

full hegemony on its people and its borders. Iraq lost these characteristics in

the aftermath of the Gulf war in 1991, with the US invasion and occupation only

augmenting the crisis.

Although Lebanon emerged from its civil wars

maintaining its image as a state, it has existed for a long time

inside an intensive care unit, disputed by armed organizations, sectarian

divisions and profound political disagreements. In Turkey, the Kurdish problem

exploded once more in the summer of 2015 following years of stumbling peace

endeavors. Ideological and sectarian ambitions as well as geopolitical concerns

have driven Iran to adopt expansionist policies in its brittle Arab

neighborhood - in Iraq, Lebanon and Syria, but also in the fragmenting Yemeni

state.

The Gulf states, especially Saudi Arabia, find that the collapse of

states such as Iraq, Syria and Lebanon on the one hand and Iran’s expansionist

push on the other constitute an imminent danger to their existence and

stability. This climate of decline and fragmentation has its greatest impact on

the crises of Iraq and Syria, which had served as foundations in the postwar

order. And this is exactly why the Syrian-Iraqi-Turkish border triangle is the

most complex and potentially explosive spots on the face of the earth.

After hesitating at length, Turkey intervened in northern Syria not just

for the sake of confronting the danger posed by the Islamic State (IS) group,

but also to tackle its considerable fears that the Syrian Kurdish Democratic

Party, closely associated with the PKK, may establish an entity in northern

Syria that will separate Turkey from its Syrian Arab neighborhood. Through its

military intervention, Turkey also seeks to maintain its role in determining

the future of Syria, the most intractable geopolitical problem of the region.

Further to the east, Ankara is ready to take part in the battle to liberate

Raqqa, IS's de facto capital, for the same reasons that motivated the Turkish

special forces to march toward Al-Bab and Manbij.

In northern Iraq, Iraqi, Kurdish, Iranian and Euro-American troops

prepare to join the battle in Mosul, while ignoring Turkish demands to

participate. For the Americans and their European allies only, Mosul represents

a battle against IS. But for the other various forces, Mosul is yet another

round in a series of battles over the region and its destiny. The Kurds believe

that their participation in the battle will lead to a reconsideration of the

borders of the Kurdish region and repaired relations between Erbil and Baghdad.

Iran and its allies in Iraq hope that Mosul will provide an opportunity to draw

a new demographic and geopolitical map in northern Iraq that will reinforce the

Shia population in the Sunni north and will open a safe and permanent passage

linking the Iranian borders to the Mediterranean in Syria.

Although it would be an oversimplification to claim that Turkey’s

objective in Mosul is to regain what the Lausanne Treaty took from it, it is

obvious that Ankara is extremely concerned about the danger threatening Iraqi

Sunnis and the ambitions Tehran seeks to achieve in the north. Baghdad on the

other hand, which right from the onset represented a secondary party in the war

with IS, continues to be a secondary party in the raging interplay in the

north.

The First World War lasted less than four years, but four more years

were needed for Western powers to agree on a new order in the region. This

time, the role of Western powers is significantly reduced. The main regional

powers are living in a moment of delicate balance. Still far from agreeing on

the lines that mark their interests, the region and its people still have a

long way to go before reaching the shore of safety and stability. Yet no one

should have any illusions about the possibility that the old regional order may

re-emerge or the potential for its survival. Whereby a victory in Mosul and the

demise of IS in Iraq will not win the war. There are still open sores in Syria,

Libya, Yemen, and elsewhere setting the stage for serious problems in the long

term.

The Arab question and the ‘shocking document’ that shaped

the Middle East.

Showing things were

not going to well, Britain’s defeat at Gallipoli was followed by an even more

devastating setback in the war against the Ottomans: The Menace of Jihad and

How to Deal with It.

French rivalry in

the Hijaz; the British attempt to get the French government to recognize

Britain’s predominance on the Arabian Peninsula; the conflict between King

Hussein and Ibn Sa’ud, the Sultan of Najd; the

British handling of the French desire to take part in the administration of

Palestine; as well as the ways in which the British authorities, in London and

on the spot, tried to manage French, Syrian, Zionist and Hashemite ambitions

regarding Syria and Palestine. The ‘Arab’ and the

‘Jewish’ question.

The British

authorities in Cairo, Baghdad and London steadily lost their grip on the

continuing and deepening rivalry between Hussein and Ibn Sa’ud,

in particular regarding the possession of the desert town of Khurma. British warnings of dire consequences if the

protagonists did not hold back and settle their differences peacefully had

little or no effect. All the while the British wanted to abolish the Sykes–

Picot agreement. The Syrian question.

One of the most

far-reaching outcomes of the First World War was the creation of Palestine,

initially under Britain as the Mandatory, out of an ill-defined area of the

southern Syrian boundary of the Ottoman Empire. The true history of the Balfour

Declaration and its implementations P.1.

The true history of the Balfour Declaration and its

implementations P.2.

The true history of the Balfour Declaration and its

implementations P.3.

The profound

effects of the British Empire’s actions in the Arab World during the First

World War can be seen echoing through the history of the 20th century. From

Versailles to the Making of the Modern Middle East P.6: The importance of

oil, the ‘Arab question’, and the British.

Sykes-Picot granted

Britain the right to administer Syria after it captured the Levant from the

Ottomans in 1918.In 1919, London conceded at the Paris Peace Conference both

Levantine entities to France that moved quickly and, aware of Hashemite

progress, settled on creating Greater Lebanon.From

Versailles to the Making of the Modern Middle East P.7: The

unresolved sectarian issue in Lebanon today.

1. William Roger Louis and P. J. Marshall, The Oxford History of the

British Empire: The Origins of the Empire: British Overseas Enterprise to the

Close of the Seventeenth Century: The Origins of Empire Vol 1, 1998, pp. 469–

70.

2. Ronald Hyam, Britain's Imperial Century 1815-1914: A Study of Empire

and Expansion (Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series), 2003, p.

49. Barbara W. Tuchman, Bible and Sword: History of Britain in the Middle East,

1982, p. 161.

3. Albert Hourani, A History of the Arab Peoples, 2005, p. 301. A. J.

Sherman, Mandate Days: British Lives in Palestine, 1918-48, 1997, p. 33.

4. Thomas E. Marston, Britain's Imperial Role in the Red Sea Area

1800-1878, p. 69.

5. Priya Satia, Spies in Arabia: The Great War and the Cultural

Foundations of Britain's Covert Empire in the Middle East, 2003, pp. 248, 252.

6. Clara Boyle, Boyle of Cairo, 1965, pp. 49– 51.

7. Ibid. Lloyd Of Dolobran, George, Baron,

Egypt Since Cromer, 1970, Vol. i, p. 75.

8. Firuz Kazemzadeh, Russia and Britain in Persia: Imperial Ambitions in

Qajar Iran, 2013, p. 340.

9. Sir George. Rendel, The sword and the olive: Recollections of

diplomacy and the Foreign Service, 1913-1954, 1957, p. 130.

10. Stephen Longrigg, ‘The Decline of the

West’, International Affairs, July 1953, p. 333.

11. Robert L. Tignor, Modernization and British Colonial Rule in Egypt,

1882-1914 (Princeton Studies on the Near East), 2015, p. 122.

12. Kennedy Trevaskis, Shades of amber: A South Arabian episode, 1968,

p. 12.

13. ‘Britain in Palestine’, SOAS Exhibition, 2012.

14. Wright, The English, pp. 44- 6.

15. Clive Jones, Britain and the Yemen Civil War, 1962? 1965: Ministers,

Mercenaries and Mandarins: Foreign Policy and the Limits of Covert Action,

2010, p. 68.

16. Timothy J. Paris, Britain, the Hashemites and Arab Rule: The Sherifian Solution, 2003, p. 290.

17. Matthew Parris And Andrew Bryson, Parting Shots, 1945, p. 239.

18. Askar H. Al-Enazy, The Creation of Saudi

Arabia (History and Society in the Islamic World), 2013, p. 34.

19. Houshang Sabahi, British Policy in Persia, 1918-1925, 1990, p. 191.

Meyer and Brysac, Kingmakers, p. 316. Gordon

Waterfield, Professional Diplomat: Sir Percy Loraine of Kirkharle,

1973, p. 164.

20. Bernard Burrows, Footnotes in the Sand: Gulf in Transition, 1953-58,

1991, p. 16.

21. James 1788-1863 Taylor and Peel, Robert Sir, 1788-1850, The Art of

False Reasoning Exemplified: In Some Extracts from the Report of Sir Robert

Peel's Speech in the Times Paper of July 7th, 1849, 2016, pp. 147, 379.

22. Trevaskis, Shades of Amber, pp. 65– 6, 132, 133.

23. Peter Hinchcliffe, John T. Ducker, Maria Holt, Without Glory in

Arabia: The British Retreat from Aden, 2012, p. 209.

24. Ibid., pp. 75, 160– 4. Spencer Mawby, British Policy in Aden and the

Protectorates 1955-67: Last Outpost of a Middle East Empire (British Foreign

and Colonial Policy), 2005, p. 152.

25. Roger Louis, Ends of British Imperialism, 2007, p. 877.

26. Alex Stirling, ‘The End of British Protection’, in Tempest (ed.),

Envoys, Vol. ii, p. 124.

27. T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, pp. 282– 3.

28. Jeremy Wilson, Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorized Biography of T. E.

Lawrence, 1989, p. 404, Elie Kedourie, In the

Anglo-Arab Labyrinth: The McMahon-Husayn Correspondence and its Interpretations

1914-1939: The McMahon-Husayn Corespondence, 2000, p.

252.

29. Friesel, ‘British Officials and the Situation in Palestine’, p. 200.

30. Peter Hennessy, Having it So Good (London, 2006), p. 438.

31. Ibid., p. 438.

32. P. M. H. Bell, France and Britain, 1900-1940: Entente and

Estrangement, 1997, Vol. ii, p. 153.

33. Zara S. Steiner and Keith Neilson, Britain and the Origins of the

First World War (The Making of the Twentieth Century), 2003, p. 83.

34. H. R. P. Dickson and Clifford Witting, Kuwait and Her Neighbours, 1956, p. 276.

35. Bruce Hoffman, Anonymous Soldiers: The Struggle for Israel,

1917-1947, 2015, pp. 398– 9.

36. William Roger Louis, ‘Britain and the Crisis of 1958’, in Roger

Louis and Roger Owen, A Revolutionary Year: The Middle East in 1958 (Library of

Modern Middle East Studies), 2002, p. 66.

37. Smith, K Simon C. Smith, Kuwait, 1950-1965: Britain, the al-Sabah, and Oil (British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship

Monographs), 2000, p. 44.

38. Ivor Lucas, Papers, p. 430.

39. Philippe Sands, Philippe Sands, Lawless World: Making and Breaking

Global Rules, 2006, p. 175.

40. Ibid., pp. 187– 93. CE. Summary by Sir Roderick Lyne, 29 January

2010. Tom Bingham, The Rule of Law (2010), pp. 123– 6. 50 Ibid., p. 110.

41. Naguib Mahfouz, Sugar Street (The Cairo Trilogy, Vol .3), 1994, p.

175.

42. Jacob Norris, ‘Repression and Rebellion: Britain’s Response to the

Arab Revolt in Palestine’, JICH, no. 1, 2008. Matthew Hughes, ‘Lawlessness was

the Law’, in Rory Miller (ed.), Britain, Palestine and Empire (Farnham, 2010),

p. 145.

43. Ibid., pp. 147– 8. Ian Cobain, Cruel Britannia: A Secret History of

Torture, 2012, pp. 102– 3.

44. Ibid., p. 103.

45. Ibid., pp. 148– 9.

46. Ibid., p. 156.

47. Spencer Mawby, British Policy in Aden and the Protectorates 1955-67:

Last Outpost of a Middle East Empire (British Politics and Society), 2005, p.

169.

48. Roger Owen, Lord Cromer: Victorian Imperialist, Edwardian Proconsul,

2004, pp. 301– 3.

49. Shepherd, Ploughing Sand, pp. 211– 14.

50. Janice J. Terry, Wafd, 1919-52: Cornerstone

of Egyptian Political Power, 1984, p. 171.

51. Victoria Schofield, Wavell - Soldier and Statesman, 2011, p. 188.

52. Eric Grove and Sally Rohan, ‘The Limits of Opposition’, in Kelly and

Gorst, Whitehall and the Suez Crisis, pp. 101, 106, 110, 112.

53. Priya Satia, Spies in Arabia: The Great War and the Cultural

Foundations of Britain's Covert Empire in the Middle East, 2010, p. 303.

54. Philip Towle, Pilots and Rebels: Use of Aircraft in Unconventional

Warfare, 1918-88, 1989, pp. 20– 1. David E. Omissi,

Air Power and Colonial Control: The Royal Air Force 1919-1939: The Royal Air

Force, 1919-39 (Studies in Imperialism), 1990, p. 163.

55. William J. Olson, Anglo-Iranian Relations During World War I, 1984,

pp. 70– 1.

56. Joseph Nero, ‘Al-Haji Amin and the British during the Second World

War’, MES, June 1984, p. 11. Jones, Britain and the Yemen Civil War, p. 95.

57. Stephen Dorrill, MI6, 2000, pp. 610, 613– 14.

58. M Jones, The 'Preferred Plan': The Anglo-American Working Group

Report on Covert Action in Syria, 1957, p. 409.

59. Ward Thomas, The Ethics of Destruction: Norms and Force in

International Relations (Cornell Studies in Security Affairs) (Ithaca, 2001),

pp. 47, 78. Dorrill, MI6, pp. 735– 7, 793.

60. Mansour Bonakdarian, Britain and the

Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1906-1911: Foreign Policy, Imperialism,

and Dissent (Modern Intellectual and Political History of the Middle East),

2006, p. 175.

61. David Gilmour, Curzon: Imperial Statesman, 2003, p. 79.

62. Sir Charles Hepburn Johnston, The Brink of Jordan, 1972, p. 78.

63. Rashid Khalidi, ‘Perceptions and Reality’, in Louis and Owen, A

Revolutionary Year in the Middle East, pp. 192– 3, 198– 9.

64. Financial Times, 23 February 2011.

65. Sir Charles Hepburn Johnston, The Brink of Jordan, 1972, p. 91.

66. Brehony, Noel and Ayman el-Desouky,

British-Egyptian Relations from Suez to the Present day (SOAS Middle East

Issues), 2007, pp. 85-7.

For updates click homepage

here