Europe

faces a banking crisis it has not wanted to admit even exists.

Among the factors responsible for the European banking crisis has been

the persistent unwillingness of bankers and regulators to acknowledge they had

a problem. Because of the politicized nature of European banking, European

governments often require their banks to have a smaller cash cushion than banks

elsewhere in the world. For example, when the European Banking Authority ran

stress tests in July to prove the banks’ stability, the banks were only

required to demonstrate a capital adequacy ratio (the percentage of assets held

in cash to cover operations and losses) of 5 percent, half the international

standard. Even with such lax standards, eight European banks still failed the

tests. Since banks need cash to engage in the business of making loans, there

is very strong resistance among European banks to valuing their assets at

market values. Any write-downs force them to redirect their free cash from

making loans to covering losses. The lower capital requirements of Europe mean

that their margin for error is always very thin.

Increasing that margin requires more cash reserves, a process known as

recapitalization. Recapitalization can be done any number of ways, but most of

the normal options are currently off the table for European banks. The

preferred method is to issue more good loans so that profits from new business

can eat away at the losses from the bad. But in a recessionary environment, new

high-quality loans are hard to find. Banks also can raise money by issuing

stock or selling assets. However, few in Europe, much less elsewhere, want to

increase their exposure to the European banking sector, largely because of

banks’ gross exposure to Europe’s sovereign debt crisis. European banks in

particular, which are in the best position to know, are reluctant to become

more entangled in each other’s affairs and often shy away from lending to one

another, even for terms as short as overnight.

Even in good times, any serious recapitalization efforts would flood the

market with stock shares and assets for sale. These are not good times.

Remember that banks are the primary purchasers of European sovereign debt and

Europe is already in a sovereign debt crisis. Adding more assets for banks to

buy would create the near-perfect buyer’s market: rock-bottom prices. There are

indeed some would-be purchasers, Sweden from within the European Union and

Turkey and Russia from without, but their combined interest adds up to merely

billions of euros, when hundreds of billions are needed.

Which brings us to the sheer size of the problem. The Europeans are

leaning toward a new regulation that would force all European banks to have a

capital adequacy ratio of 9 percent, hoping that such a change would decisively

end speculation that Europe’s banks face problems. It will not.

According to the European Banking Authority, the institution that is

responsible for carrying out stress tests, two-thirds of Europe’s banks are

currently below the 9 percent threshold, and that assumes no past or future

reduction in the value of sovereign bonds for any European governments, no new

sovereign bailouts that damage investor confidence or asset values, no mortgage

crisis, no new bank collapses in Europe akin to that of Franco-Belgian bank Dexia and no renewed recession. Simply increasing capital

adequacy ratios to 9 percent will cost about 200 billion euros (about $270

billion). The regulation also assumes that all European banks have been

scrupulously honest in their reporting; Dexia, for

example, shuffled assets between its trading and banking books to generate a

misleading capital adequacy ratio of 12 percent, when the reality was in the

vicinity of 6 percent. Forcing the banks to have a thicker cushion is certainly

a step in the right direction, but the volume is insufficient to resolve any of

the problems outlined to this point, and the latest rumor out of Europe’s

pre-summit negotiations is that perhaps only 80 billion euros is actually

needed.

If the banks cannot recapitalize themselves, the only remaining options

are state-driven recapitalization efforts. Here, again, current circumstances

hobble possible actions. The European sovereign debt crisis means many

governments are already facing great stresses in meeting normal financing

needs, doubly so for Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Italy, Belgium and Spain. No

eurozone states have the ability to quickly come up with several hundred

billion euros in additional funds. Keep in mind that, unlike the United States,

where the Federal Reserve plays a central role in bank regulation and

remediation, the European Central Bank has no role whatsoever. The individual

central banks of the various eurozone states lack the control over monetary

policy to build the sort of highly liquid support mechanisms required to

sequester and rehabilitate damaged banks. Such central bank actions remain in

the arsenal of the non-eurozone states, the United Kingdom, for one, has been

using such monetary policy tools for three years now. However, for the eurozone

states, the only way to recapitalize is to come up with cash, and as Europe’s

financial crises deepen, that’s becoming ever harder to do.

There is one other option that the eurozone states do have: the European

Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), better known as the European bailout fund,

which manages the Greek, Irish and Portuguese bailouts. With its recent

amendments, the EFSF can now legally assist European banks as well as European

governments. But even this mechanism faces three complications.

First, the EFSF has yet to bail out a bank, so it is unclear what

process would be followed. The French have indicated they would like to tap the

facility to recapitalize their banks because they see it as being politically

attractive (and not using just their money). The Germans have indicated that

should a bank tap the facility then the sovereign that regulates the bank must

commit to economic reforms; the EFSF, therefore, should be a last resort. Not

only is there not yet a process for EFSF bank bailouts, but there also is not

yet an agreement on who should hold the process. Even if the Germans get their

way on the EFSF, remediation and supervisory structures must first be built.

Second, the EFSF is a very new institution with only a handful of staff.

Even if there were full eurozone agreement on the process, the EFSF is months

away from being able to implement policy. And if the EFSF is going to have the

ability to restructure banks, that power is, for now, directly in opposition to

EU treaties that guarantee all banking authority to the member-state level.

Finally, the EFSF is fairly small in terms of funding capacity. Its

total fundraising ceiling is only 440 billion euros, 268 billion of which it

has already committed to the bailouts of Greece, Ireland and Portugal over the

course of the next three years. Unless the facility is significantly expanded,

it simply will not have enough money to serve as a credible bank-financing

tool. To handle all of the challenges the Europeans are hoping the EFSF will be

able to resolve, yet it is estimated the facility will need its capacity

expanded to 2 trillion euros. Finding ways to solve that problem

likely will dominate the European summits being held during the next few days.

Basically France wants to have the European Central Bank at the centre of any effort to increase the firepower of the

bailout facility, the EFSF. Germany does not. Germany instead wants bondholders

to face much steeper "haircuts" on Greek debt. France does not - in

part because of what it might mean for some politically important French banks.

Sovereign Debt: The Expected

Problem

A meeting of eurozone ministers today (Oct. 21) is largely dedicated to

the topic, as is the Oct.

23 summit of EU heads of government. Yet European governments continue to consider

the banking sector largely only within the context of the ongoing sovereign

debt crisis.

This is exemplified in Europeans’ handling of the Greek situation. The

primary reason Greece has not defaulted on its nearly 400-billion euro

sovereign debt is that the rest of the eurozone is not forcing Greece to fully

implement its agreed-upon austerity measures. Withholding bailout funds as

punishment would trigger an immediate default and a cascade of disastrous

effects across Europe. Loudly condemning Greek inaction while still slipping

Athens bailout checks keeps that aspect of Europe’s crisis in a holding

pattern. In the European mind, especially the Northern European mind, a handful

of small countries that made poor decisions are responsible for the European

debt crisis, and while the ensuing crisis may spread to the banks as a

consequence, the banks themselves would be fine if only the sovereigns could

get their acts together.

This is an incorrect assumption. If anything, Europe’s banks are as

damaged as the governments that regulate them.

When evaluating a problem of such magnitude, one might as well begin

with the problem as the Europeans see it, namely, that their banks’ biggest

problem is rooted in their sovereign debt exposure.

The state-bank contagion problem is fairly straightforward within

national borders. As a rule the largest purchaser of the debt of any particular

European government will be banks located in the particular country. If a

government goes bankrupt or is forced to partially default on its debt, its

failure will trigger the failure of most of its banks. Greece does indeed

provide a useful example. Until Greece joined the European Union in 1981,

state-controlled institutions dominated its banking sector. These institutions’

primary reason for being was to support government financing, regardless of

whether there was a political or economic rationale justifying that financing.

The Greeks, however, have no monopoly on the practice of leaning on the banking

sector to support state spending. In fact, this practice is the norm across

Europe.

Spain’s regional banks, the cajas, have become

infamous for serving as slush funds for regional governments, regardless of the

government in question’s political affiliation. Were the cajas

assets held to U.S. standards of what qualifies as a good or bad loan, half the

cajas would be closed immediately and another third

would be placed in receivership. Italian banks hold half of Italy’s 1.9

trillion euros in outstanding state debt. And lest anyone attempt to lay all

the blame on Southern Europe, French and Belgian municipalities as well as the

Belgian national government regularly used the aforementioned Dexia in a somewhat similar manner.

Yet much debt remains for outsiders to own, so when states crack, the

damage will not be held internally. Half or more of the debt of Greece,

Ireland, Portugal, Italy and Belgium is in foreign hands, but like everything

else in Europe the exposure is not balanced evenly, and this time, it is

Northern Europe, not Southern Europe, that is exposed. French banks are more

exposed than any other national sector, holding an amount equivalent to 8.5

percent of French gross domestic product (GDP) in the debt of the most

financially distressed states (Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Italy, Belgium and

Spain). Belgium comes in second with an exposure of roughly 5.5 percent of GDP,

although that number excludes the roughly 45 percent of GDP Belgium’s banks

hold in Belgian state debt.

When Europeans speak of the need to recapitalize their banks, creating

firebreaks between cross-border sovereign debt exposure dominates their

thoughts, which explains why the Europeans belatedly have seized upon the IMF’s

original 200 billion-euro figure. The Europeans are hoping that if they can

strike a series of deals that restructure a percentage of the debt owed by the

Continent’s most financially strapped states, they will be able to halt the

sovereign debt crisis in its tracks.

This plan is flawed. The figure, 200 billion euros, will not cover

reasonable restructurings. The 50 percent writedowns

or “haircuts” for Greece under discussion as part of a revised Greek bailout,

likely to be announced at the end of the upcoming Oct. 23 EU summit, would

absorb more than half of that 200 billion euros. A mere 8 percent haircut on

Italian debt would absorb the remainder.

Moreover, Europe’s banking problems stretch far beyond sovereign debt.

Before one can understand just how deep those problems go, we must examine the

role European banks play in European society.

The Centrality of European

Banking

For example, several differences between the European and American banking

sectors exist. By far the most critical difference is that European banks are

much more central to the functioning of European economies than American banks

are to the U.S. economy. The reason is rooted in the geography of capital.

Maritime transport is cheaper than land transport by at least an order

of magnitude once the costs of constructing road and rail infrastructure is

factored in. Therefore, maritime economies will always have surplus capital

compared to their land transport-based equivalents. Managing such excess

capital requires banks, and so nearly all of the world’s banking centers form

at points on navigable rivers where capital richness is at its most extreme.

For example, New York is where the Hudson meets the Atlantic Octen, Chicago is at the southernmost extremity of the

Great Lakes network, Geneva is near the head of navigation of the Rhone, and

Vienna is located where the Danube breaks through the Alps-Carpathian gap.

Unity differentiates the U.S. and European banking system. The American

maritime network comprises the interconnected rivers of the Greater Mississippi

Basin linked into the Intracoastal Waterway, which allows for easy transport

from the U.S.-Mexico border on the Gulf of Mexico all the way to the Chesapeake

Bay. Europe’s maritime network is neither interlinked nor evenly shared.

Northern Europe is blessed with a dozen easily navigable rivers, but none of

the major rivers interconnect; each river, and thus each nation, has its own

financial capital. The Danube, Europe’s longest river, drains in the opposite

direction but cuts through mountains twice in doing so. Some European states

have multiple navigable rivers: France and Germany each have three major ones.

Arid and rugged Spain and Greece, in contrast, have none.

The unity of the American transport system means that all of its banks

are interlinked, and so there is a need for a single regulatory structure. The

disunity of European geography generates not only competing nationalities but

also competing banking systems.

Moreover, Americans are used to far-flung and impersonal capital funding

their activities (such as a bank in New York funding a project in Nebraska)

because of the network’s large and singular nature. Not so in Europe. There,

regional competition has enshrined banks as tools of state planning. French

capital is used for French projects and other sources of capital are viewed

with suspicion. Consequently, Americans only use bank loans to fund 31 percent

of total private credit, with bond issuances (18 percent) and stock markets (51

percent) making up the balance. In the eurozone roughly 80 percent of private

credit is bank-sourced. And instead of the United States’ single central bank,

single bank guarantor and fiscal authority, Europe has dozens. Banking regulation

has been expressly omitted from all European treaties to this point, instead

remaining a national prerogative.

As a starting point, therefore, it must be understood that European

banks are more central to the functioning of the European system than American

banks are to the American system. And any problems that might erupt in the

world of European banks will face a far more complicated restitution effort

cluttered with overlapping, conflicting authorities colored by national biases.

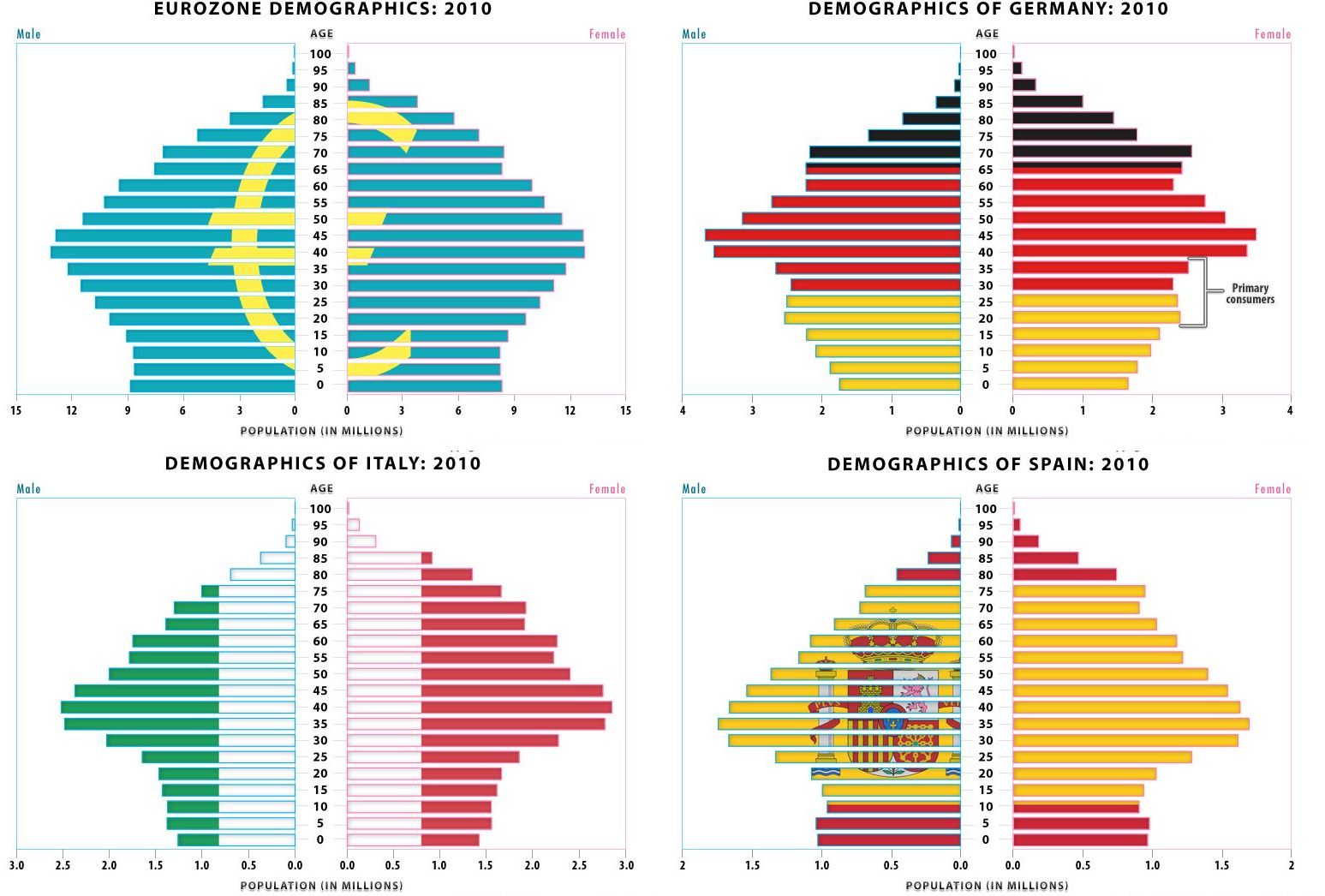

Demographic Limitations

European banks also face less long-term growth. The largest piece of

consumer spending in any economy is done by people in their 20s and 30s. This

cohort is going to college, raising children and buying houses and cars. Yet

people in their 20s and 30s are the weakest in terms of earning potential. High

consumption plus low earning leads invariably to borrowing, and borrowing is

banks’ mainstay. In the 1990s and 2000s much of Europe enjoyed a bulge in its

population structure in precisely this young demographic, particularly in

Southern European states, generating a great deal of economic activity, and

from it a great deal of business for Europe’s banks.

But now, this demographic has grown up. Their earning potential has

increased, while their big surge of demand is largely over, sharply curtailing

their need for borrowing. In Spain and Greece, the younger end of population

bulge is now 30; in Italy and France it is now 35; in Austria, Germany and the

Netherlands it is 40; and in Belgium it is 45. Consumer borrowing in general

and mortgage activity in particular probably have peaked. The small sizes of

the replacement generations suggests there will be no recoveries within the

next few decades. (Children born today will not hit their prime consumptive age

for another 20 to 30 years.) With the total value of new consumer loans likely

to stagnate (and more likely, decline) moving forward, if anything there are

now too many European banks competing for a shrinking pool of consumer loans.

Europe is thus not likely to be able to grow out of any banking problems it

experiences. The one potential exception is in Central Europe, w here the

population bulges are on average 15 years younger than in Western Europe. The

younger edge of the Polish bulge, for example, is only 25. In time, these

states may be able to grow out of their problems. Either way, the most

lucrative years for Western European banking are over.

Too Much Credit

Germany has extremely high capital accumulation and extremely competent

economic management. One of the many results of this pairing is extremely

inexpensive capital costs. When Germans, governments, corporations or

individuals, borrow money, it is accepted as a near-fact that they will pay

back what they owe, on time and in full. Reflecting the high supply and low

risk, German borrowing rates for governments and corporations have long been in

the low to mid single digits.

The further you move from Germany the less this pattern holds. Capital

availability shrivels, management falters and the attitude toward contract law

(or at least as defined by the Germans) becomes far less respectful. As such,

Europe’s peripheral economies, most notably its smaller peripheral economies,

have normally faced higher borrowing costs. Mortgage rates in Ireland stood

near 20 percent less than a generation ago. Government borrowing rates in

Greece have in the past topped 30 percent.

With that sort of difference, it is not difficult to see why many

European states have striven for inclusion in first, the European Union, and

second, the eurozone. Each step of the European integration process has brought

them closer in financial terms to the ultra-low credit costs of Germany. The

closer the German association, the greater the implicit belief that German

financial resources would help them in a crisis (despite the fact that EU

treaties explicitly rejected this).

The dawn of the eurozone era prompted lenders and investors to take this

association to an extreme. Association with Germany shifted from lower lending

rates to identical lending rates. The Greek government could borrow at rates

that only Germany could demand in the past. Irish borrowers were able to

qualify for 130 percent mortgages at 4 percent. Compounding matters, the

collapse of borrowing costs and the explosion of loan activity occurred at the

same time as Southern Europe’s demographic-driven consumption boom. It was the

perfect storm for explosive banking growth, and it laid the groundwork for a

financial collapse of unprecedented proportions.

Drastic increases in government debt are the most publicly visible

outcome, but it is far from the only one. The least visible outcome is that

extraordinarily cheap credit to consumers triggers an explosion in demand that

local businesses cannot hope to fill. The result is unprecedented trade

deficits as money borrowed from foreigners is used to purchase foreign goods.

Cyprus, Greece, Portugal, Bulgaria, Romania, Lithuania, Estonia and Spain, all

states whose cheap labor when compared to the Western European core should

encourage them to be massive exporters, instead have run chronic trade deficits

in excess of 7 percent of GDP. Most routinely broke 10 percent. Such

developments do not directly harm the banks, but as credit costs return to more

rational levels, and in the ongoing debt crisis borrowing costs for most of the

younger EU members have tripled and more, consumption is coming to a halt. In

the few European markets that demographically may be able to generate

consumption-based growth in the years ahead, credit is drying up.

Foreign Currency Risk

Much of this lending into weaker locations was carried out in foreign

currencies. For the three states that successfully made the early sprint into

the eurozone, Estonia, Slovenia and Slovakia, this was a nonfactor. For those

that did not make the early leap into the eurozone it was a wonderful way to

get something for nothing. Their association with the European Union resulted

in the steady strengthening of their currencies. Since 2004, the Polish, Czech,

Romanian and Hungarian currencies gained roughly one-third versus the euro,

driving down the monthly payments on any euro-denominated loan. That inverted,

however, in the 2008 financial crisis. Then, every regional currency but the

Czech koruna (and Bulgarian lev, which is pegged to the euro) gave back their

gains. For Central Europeans who had taken out loans when their currencies were

at their highs, payments ballooned. More than 10 percent of Polish and

Hungarian mortgages are now delinquent, largely because of currency movements.

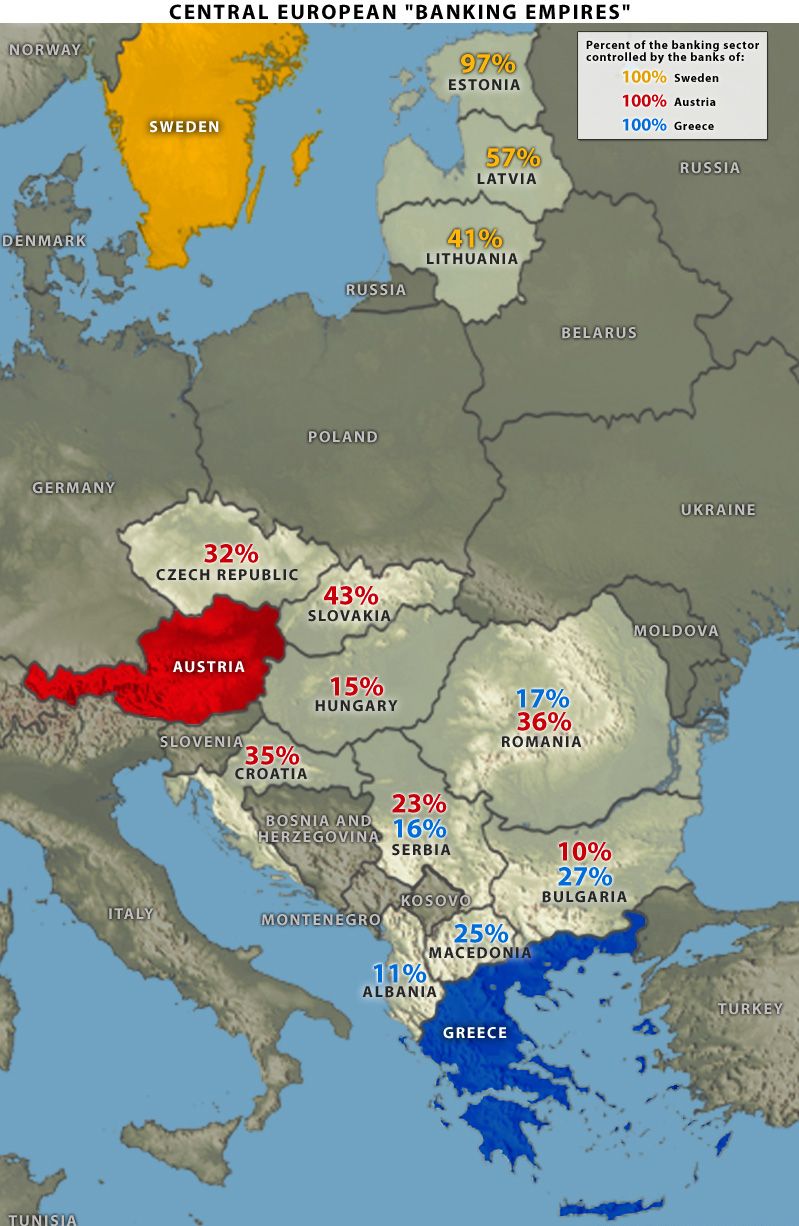

New Banking ‘Empires’

The cheap credit of the eurozone’s first decade allowed several

peripheral European states a rare opportunity to expand their network of

influence, even if they were not in the eurozone themselves. They could borrow

money from core European banking centers like Germany, France, Switzerland and

the Netherlands and pass that money on to previously credit-starved markets. In

most cases, such credit was offered without the full cost-increase that these

states’ poorer and smaller statures would have justified. After all, these

would-be financial centers had to undercut the more established European

financial centers if they were to gain meaningful market share. This pushed far

more credit into Central Europe than the region otherwise would have attracted,

speeding up the development process at the cost of poor underwriting and a

proliferation of questionable lending practices. The most enthusiastic crafters

of new banking empires have been Sweden, Austria, Spain and Greece.

- Sweden has the happiest record of any of the states that engaged in such

expansionary lending. Being one of the richest countries in Europe and yet not

being a member of the eurozone, Sweden did not experience a credit expansion

nearly as much as other states, instead it served as a conduit for that credit,

augmented by its own, to its former imperial territories. Alone among the

forgers of new banking empires, Sweden’s superior financial stability has

allowed it (so far) to continue financial activities in its target markets,

Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Denmark, despite the ongoing financial crisis.

But instead of lending, Swedish banks are now purchasing regional banks

outright. Swedish command of the Danish banking sector, for example, has

increased by 80 percent since the crisis. Through its new local subsidiaries, Swedish

banks now lend more in per capita terms to Danes than they do to their own

citizens, and there is no longer a domestic Estonian banking sector, it is 97

percent Swedish-owned. Such expansionary activity is likely to continue so long

as Sweden can sustain it, as there is a geopolitical angle to Sweden’s effort:

It is seeking to deepen its regional influence not only for economic purposes,

but also to mitigate the rising role of its longtime competitor, Russia.

- Austria has tapped not only eurozone credit but also taken advantage

of favorable carry trades to serve as a conduit for Swiss franc credit into

Central Europe. Just as Sweden is using foreign capital to re-create its

historic sphere of influence in the Baltic, Austria is doing the same in the

lands of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. Now, the majority of all mortgages

in Poland, Hungary, Croatia and Romania, and a sizable minority in Austria, are

denominated in foreign currencies, courtesy of Austrian banking activity. With

the Swiss franc now locked in at record highs, many of these mortgages are not

serviceable. The Hungarian government has felt forced to abrogate the terms of

many of these loans, knowing that the Austrian banks are now so overexposed to

Central Europe that they have no choice but to take the losses. As the

financial crisis has continued apace, Austria has found itself with more

exposure, fewer domestic resources and greater vulnerability to external forces

than Sweden. So instead of being able to take advantage of regional weakness,

it is finding itself losing market share both at home and in its would-be

financial empire to Russia.

- Spain’s banking empire isn’t even in Europe. Spanish firms

BBVA-Compass and Santander have used the cheap euro credit to massively expand

credit to Latin America. And Spain’s expansion took a somewhat novel route: The

combination of cheap lending at home and in Latin America encouraged more than

a million Latin American Spanish speakers to relocate to Spain and gain

citizenship. To smooth the naturalization process, Madrid mandated that the new

Spaniards be granted top-notch credit, a factor that only added to an already

hyperactive construction sector. Spanish banks’ nearly 500 billion-euro

exposure to Latin America is, for now, holding; only time will tell its impact

to Spain’s bottom line.

The Greek government used its access to cheap credit to build up debt

levels that are now the subject of much discussion across Europe. But much less

is made of its banks, who encouraged consumers both at home and across the

southern Balkans to increase their own debt levels. Being the least experienced

of the four would-be financial centers, Greek banks offered the steepest credit

breaks to the countries with the weakest repayment potential. Like Spain,

Greece also did not make EU membership a condition for lending; vast volumes

accordingly were fed into Macedonia, Serbia and even Albania.

Housing Bubbles

Large volumes of suddenly cheap credit made available to eager consumers

obviously generated a series of sizable housing bubbles.

Spain’s tapping of European credit markets also underwrote the largest

housing boom in Europe. More construction projects have been completed in Spain

in recent years than in Germany, France, Italy and the United Kingdom combined.

The construction sector, both commercial and residential, has now collapsed and

there are about 1 million homes now sitting vacant in a country with just 16.5

million families. Outstanding loans to various real estate interests total some

400 billion euros, all backed by collateral that has lost 20 percent of its

value since the housing market peaked.

In relative terms, Ireland actually did more than Spain. At its peak,

nearly 10 percent of Irish gross national product was dependent upon

construction, with 70 percent of that purely from residences. Half of the

mortgages extended during the Irish real estate boom were made at the peak of

the market between 2006 and 2008. That sector remains in the midst of a fairly

rapid collapse. Residential home prices have reduced by half since their peak

in 2007 and are showing few signs of stabilizing. The Irish government hopes

that with their eurozone bailout package, their banking sector will become

functional again by 2020. Until then, Ireland in effect has no banking sector

and has been financially sequestered from the rest of the eurozone.

Two other European states, the United Kingdom and Sweden, have both

experienced massive increases in home price growth, and both suffered from

price corrections due to the 2008 financial crisis. But prices in both markets

have recovered smartly, with Sweden even bouncing back above its pre-crisis

highs. Sweden, in fact, is still experiencing a massive housing boom, with

annual mortgage credit still expanding at a 30 percent annualized rate.

For updates click homepage

here