By Eric Vandenbroeck

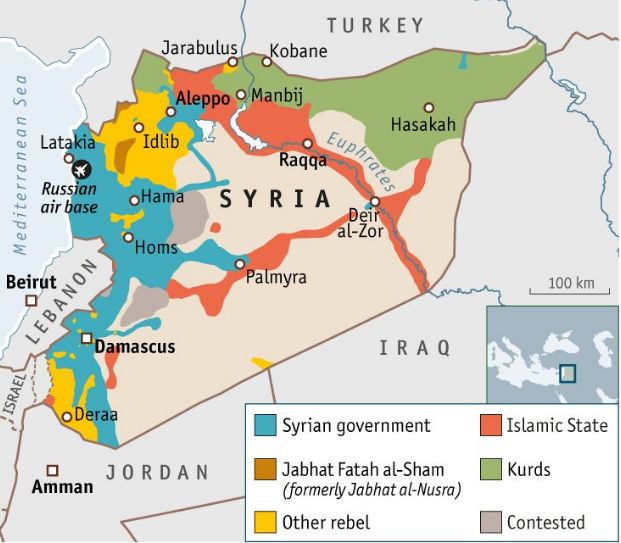

Turkish tanks and jets backed by planes from a U.S.-led coalition

launched an offensive into Syria today. President Erdogan said the operation

was targeting both Islamic State and the Kurdish PYD party. As I suggested on 25 May, the effect of the operation

will be to preserve a corridor between Turkey and ISIS. Turkey told the Kurdish

YPG that when they do not move back east across the Euphrates River within a

week that Turkish troops will drive them back by force. It is expected that U.S.intelligence or/and special operations forces on the

ground will work alongside Turkish backed rebels fighting the Islamic State.

Following

an overview of the conflict and international rivalry's

The four overlapping

conflicts.

The core conflict is between forces loyal to President Bashar al-Assad

and the rebels who oppose him. Over time, both sides fractured into multiple

militias, including local and foreign fighters, but their fundamental

disagreement is over whether Assad’s government should stay in power.

This opened a second conflict: Syria’s ethnic Kurdish minority took up

arms amid the chaos. The Kurds carved out a de facto mini-state called Rojava

and have gradually taken territory they see as Kurdish — sometimes with backing

from the United States, which at times sees the Kurds as an ally against

jihadist groups. While Assad has not focused on fighting the Kurdish groups,

they are opposed by neighboring Turkey, which is in conflict with its own

Kurdish minority.

The third conflict involves the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or

ISIL, which emerged out of infighting among jihadist groups. In 2014, the

Islamic State seized large parts of Syria and Iraq, and it declared that

territory its caliphate. The group has no allies and is at war with all other

actors in the conflict.

The fourth, and most complex, dynamic may be the crisscrossing foreign

interventions, which have grown steadily. Assad receives vital support from

Iran and Russia, as well as the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah. The rebels

are backed by the United States and oil-rich Arab states like Saudi Arabia.

These foreign powers have different agendas, but all pursue them by ramping up

Syria’s violence, helping to perpetuate the war.

How it began

On the surface, the conflict began in 2011 with the Arab Spring.

Syrians, like other peoples across the region, rose up peacefully against their

authoritarian government. Mr. Assad cracked down violently. Communities took up

arms to defend themselves, then fought back in what became a civil war. Some

soldiers joined the rebels, but not enough to win.

But that alone does not explain Syria’s disintegration. It is now clear

that the state was weak in ways that made it inherently unstable and prone to

violence.

The government was dominated by a minority group. Over decades, Syria’s

religious and ethnic divides had taken on greater political importance, making

the ruling minority fearful and reactive. Assad had strong support among the

military and security services, but not the broader population, making violence

more tempting. The instability was deepened by the fact that rural Syrians had

moved to cities in large numbers in recent years, driven in part by droughts

linked to climate change.

Fighting, once it began, was worsened by several external factors. A

decade of war in neighboring Iraq had produced battle-hardened extremist groups

that now flowed into Syria. Iraq’s political troubles in 2011 and 2012 helped

open space for the Islamic State. During this time, Syria was sucked into the

regional power struggle between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

International rivalry and the

battle for Syria

Five countries are playing a major role in Syria, each with different

agendas. Their interventions have locked the war into an ever-worsening

stalemate.

Iran was first, sending supplies and soldiers to prop up Assad. Iran

sees Syria as crucial to its regional strategy: It provides access to Lebanon

and therefore Hezbollah, a group Tehran uses for regional influence and as a

counterweight to Israel, whose nuclear weapons it fears.

Saudi Arabia supported Syria’s rebels in the hopes of replacing Mr.

Assad with a friendlier government and of countering Iran’s influence. Saudi

Arabia and Iran have been rivals for decades, fighting something like a cold

war for regional dominance. (Other Arab states like Jordan, Qatar and the

United Arab Emirates have also backed the rebels.)

Their struggle has escalated for several reasons: Iran’s growing power;

the regional power vacuum that opened with the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003

in Iraq; more political vacuums opened by the Arab Spring; a hawkish new king in Saudi Arabia; and Saudi

fears that the United States is becoming less hostile toward Iran.

The United States funnels weapons to Syria’s rebels. It did so initially

out of opposition to Mr. Assad, a longtime enemy, and later to encourage those

groups to fight the Islamic State. The United States has also armed Kurdish

groups against the Islamic State.

Turkey sheltered Syrian rebels and ushered in foreign recruits, seeking

to undermine and perhaps topple Assad. Later, the country also acted to counter Syrian Kurdish groups, fearing that they could

strengthen Kurdish insurgents in Turkey. Whereby now it appears that the US is

willing to work alongside Turkish troops fighting the Islamic State.

Russia has backed Assad from the beginning, selling him arms and

providing diplomatic cover at the United Nations. Syria is one of Russia’s last

remaining allies, and it is where Moscow maintains its only military bases

outside the former Soviet Union. Russian forces intervened in 2015, at a time

when Assad appeared to be losing ground.

But where foreign interventions were intended to end the war have

instead entrenched it in a stalemate in which violence is self-reinforcing and

the normal avenues for peace are all closed.

The fact that the underlying battle is multiparty rather than two-sided

also works against resolution.

Also, most civil wars end when one side loses. Either it is defeated

militarily, or it exhausts its weapons or loses popular support and has to give

up. About a quarter of civil wars end in a peace deal, often because both sides

are exhausted.

That might have happened in Syria: The core combatants, the government

and the insurgents who began fighting it in 2011, are quite weak and, on their

own, cannot sustain the fight for long.

But they are not on their own. Each side is backed by foreign powers,

including the United States, Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and now Turkey, whose

interventions have suspended the usual laws of nature. Forces that would

normally slow the conflict’s inertia are absent, allowing it to continue far

longer than it otherwise would.

Government and rebel forces are supplied from abroad, which means their

arms never run out. They also both draw political support from foreign

governments who do not feel the war’s costs firsthand, rather than from locals

who might otherwise push for peace to end their pain. These material and human

costs are easy for the far richer foreign powers to bear.

Foreign sponsors do not just remove mechanisms for peace. They introduce

self-reinforcing mechanisms for an ever-intensifying stalemate.

Whenever one side loses ground, its foreign backers increase their

involvement, sending supplies or air support to prevent their favored player’s

defeat. Then that side begins winning, which tends to prompt the other’s

foreign backers to up their ante as well. Each escalation is a bit stronger

than what came before, accelerating the killing without ever changing the war’s

fundamental balance.

This has been Syria’s story almost since the beginning. In late 2012, as

Syria’s military suffered defeats, Iran intervened on its behalf. By early 2013,

government forces rebounded, so wealthy Gulf states flooded support to the rebels.

Several rounds later, the United States and Russia have joined the fray.

These foreign powers are strong enough to match virtually any

escalation. None can force an outright victory because the other side can

always counter, so the cycle only continues. Even natural fluctuations in the

battle lines can trigger another round.

What about the atrocities

There have been atrocities on all sides, but forces loyal to Assad have

committed by far the most. Because his government is so weak, its support base

is small and its military has suffered heavy defections, Assad seems to believe

he can regain control only by violently coercing Syrians into submission. That

has included using chemical weapons, barrel bombs and starvation.

Because neither Assad nor the rebels are strong enough to win, the battle lines push back and forth, rolling across communities

in waves of destruction that kill thousands but accomplish little else.

Foreign interventions have made those shifting front lines even bloodier

and have deepened the stalemate. As a result, the overall violence kills more

Syrians without altering the conflict’s underlying dynamics.

The years of chaos have destroyed basic order in Syria. As often happens

in lengthy civil wars, militias have filled the vacuum. Their leaders often

behave more as warlords, forcibly extracting resources from local communities.

This practice has been carried out by rebel militias and some that support the

government.

The rise of the Islamic State has worsened all of these trends. The

jihadist group has provided another set of shifting battle lines, introduced

more warlords, compelled more foreign interventions and, most of all, put

communities under its tyrannical, fanatical rule.

Why it is not a religious war

There is nothing innately religious about Syria’s war, but its broader

political forces have played out along religious lines. To understand why, it

helps to start about 100 years ago.

After World War I, France

took control of the territory of the defeated Ottoman Empire that is now Syria. France ruled through

minority groups that would be too small to hold power without outside support.

That included Alawites, followers of a branch of Shiite Islam, who joined the

military in large numbers. The last French troops left in 1946, and a long

period of turmoil followed. Syria’s military consolidated power in a 1970 coup

led by Hafez al-Assad, an Alawite general and the father of Bashar al-Assad.

Syria’s authoritarian government favored Alawites and other minorities,

widening social and political divides along sectarian lines. A sectarian civil

war next door in Lebanon and the rise of Sunni religious politics widened them

further, and Alawites continued to cluster in positions of power. The country’s

Sunni Arab majority came to feel, at times, that they were underserved.

Minority governments like Syria’s tend to be unstable. They sometimes

fear discrimination or worse should they lose power, and can see the majority

group as a potential threat rather than a base of support. This can make them

more willing to use violence to hold on to power, as Assad did when his forces

opened fire on peaceful protesters in 2011.

As the war has worsened, many Syrians have based their allegiance on

sectarian identity. But this is not because they are motived primarily by

religious or ethnic concerns. Rather, it is defensive. They fear that the other

side will target them for their background, so they feel safe only with their

own people. This contributes to atrocities: If Alawites are seen as innately

pro-Assad, then Sunni militias could conclude that all Alawite civilians are a

threat and treat them accordingly, which prompts more defensive sorting.

At the same time, the Iran-Saudi Arabia proxy war is also playing out

along sectarian lines, with the Saudis backing Sunnis and Iran backing Shiites

across the region. For both countries, sectarianism is a tool by which they can

cultivate proxy forces and stir up fear of the other side.

Where did ISIS come from

The group has its roots in two earlier wars and the foreign occupations

that followed: the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the American-led

invasion of Iraq in 2003. In the first, Sunni Arab volunteers fought alongside

Afghan rebels, later forming the global jihadist movement, including Al Qaeda.

In the second, Al Qaeda and other Sunni groups flooded to Iraq to fight both

the Americans and Iraq’s Shiite majority.

A key name is Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a Jordanian extremist who fought in

Afghanistan in the 1990s and Iraq in the 2000s.

Zarqawi’s views and methods were even more extreme and theatrical than

Al Qaeda’s. He flourished in Iraq’s war, using tactics now associated with the

Islamic State: videotaped beheadings, mass killings of fellow Muslims deemed

nonbelievers and attacks meant to incite a Sunni-Shiite war.

Al Qaeda invited Zarqawi to rebrand his group as Al Qaeda in Iraq, but

the two factions argued over strategy and ideology, setting them up for

conflict a decade later in Syria.

Zarqawi was killed in 2006, and his group declined as Sunni Iraqis

turned against it. Later, Iraq’s Shiite-dominated government grew increasingly

authoritarian and sectarian, alienating the minority Sunni. It also purged many

experienced military and security officers, replacing them with political

loyalists.

The successor to Zarqawi’s group, then calling itself the Islamic State

in Iraq, exploited these conditions in 2011 and 2012 to reconstitute itself,

for example by breaking extremists out of Iraqi prisons. Its leader, Abu Bakr

al-Baghdadi, combined Zarqawi’s views with an apocalypticism taking hold amid

the region’s upheaval.

Baghdadi sent a top officer into Syria’s war to set up a new Al Qaeda

franchise: the Nusra Front, now known as the Levant Conquest Front. In 2013,

Mr. Baghdadi declared himself commander of all Al Qaeda forces in Iraq and

Syria. After years of tense partnership with Al Qaeda, the groups finally

split. Baghdadi, his force now rebranded

as the Islamic State, invaded Syria to fight his former Qaeda allies.

The Islamic State carved out a ministate in Syria’s chaos, then used it

as a base to invade Iraq in 2014. It repeated Zarqawi’s worst tactics on a far

larger scale, committing acts of genocide and mass murder in the Middle East

and abroad, and attracting foreign recruits from rich and poor countries alike.

Three sets of refugee problems

The war in Syria has produced nearly five million refugees. The exodus

has created three sets of problems, all dire: a humanitarian crisis for the

refugees themselves, a potential crisis for the countries that host them and a

political crisis in Europe over what to do.

Syrian refugees face disease and malnutrition. Host countries often bar

them from working, meaning that families cannot provide for themselves. Many

Syrian children are deprived of education, a problem that could hinder them for

life.

Most Syrian refugees are in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, neighboring

countries that lack the necessary resources to help them. The influx could be

destabilizing, particularly in Jordan and Lebanon where Syrian refugees now

make up a large share of the population.

Many refugees, unable to tolerate life in the camps, have braved the

dangerous journey to Europe. But European voters have largely rejected them,

supporting extreme measures to keep out Syrians and other migrants.

European leaders at one point suspended search-and-rescue missions in

the Mediterranean, partly in response to complaints that saving refugees’ lives

might encourage more to make the journey. Leaders of the campaign to get

Britain to leave the European Union based their argument partly on opposition

to accepting Syrian refugees.

Europe’s attitude appears driven by a combination of economic downturn;

hostility toward the European Union, which allows unlimited migration among

member states; and demographic anxiety rooted in longer-term trends that have

made populations more diverse.

As a result, many refugees are stuck in camps in Italy and Greece. Many

others die trying to reach Europe. European countries, along with the United

States and Canada, have absorbed thousands of refugees, but not nearly enough

to alter the underlying crisis.

The current situation with

Turkey

For Turkey the Syrian civil war has been disastrous. Five years ago,

when peaceful protest against Syrian president Bashar al-Assad began as part of

the Arab Spring, Turkey looked set to benefit most from the anticipated

regional shift. The ruling AKP’s ‘zero problems’ policy had transformed

Turkey’s economic and political ties with the traditionally hostile Middle

East. Premier Erdogan’s party was hailed by western leaders and regional

activists as a model for Islamic democracy, the economy was booming and moves

towards resolving Ankara’s long-standing unrest with its Kurdish population

were cautiously being made.

Today, the picture is very different. Erdogan, now president, is widely

condemned for his creeping authoritarianism. Crackdowns on journalists and

academics have grown steadily as the AKP founder tightened his grip on power,

and accelerated sharply after an attempted military coup against him in July.

The PKK’s insurgency has resurfaced in the East, while the economy has been

affected by the arrival of 2.7 million Syrian refugees and a decline in tourism

following a string of ISIS and Kurdish terrorist attacks. Regionally, Turkey’s

dreams of playing a leading role in a post-Arab Spring Middle East seem to be

in tatters.

Turkey’s policies in Syria have played a major role in weakening its

position. Determined to topple Assad, Ankara facilitated the flow of foreign

funds and weapons to disparate groups in the rebellion, often turning a blind

eye and even encouraging the rise of radical jihadists such as ISIS. This

contributed to the division and weakness of the opposition, helping prolong the

war, and allowed ISIS to form cells in Turkey that it would later activate

against Ankara.

Similarly, Turkey used its influence with the rebels and international

powers to exclude the PYD. This reinforced the Syrian Kurdish group’s mistrust

of the rebels prompting them to stand alone and carve out their own autonomous

territory, known locally as ‘Rojava,’ in northern Syria. As a result, Turkey

now faces what it considers a PKK proto-state along its southern border,

offering strategic depth and inspiration for attacks inside Turkey. Indeed the

reigniting of violence in Turkey’s Kurdish regions was initially prompted by

outrage at Ankara’s policies towards Rojava.

Turkey’s regional position was likewise hit. Its historically close ties

with the U.S. was strained by Obama’s unwillingness to intervene directly

against Assad despite Erdogan’s assumption that he would, due to Turkey’s

initial reluctance to join the anti-ISIS campaign and then over Washington’s

support for the PYD in its fight against the jihadists. Moscow’s foray into the

war backing Assad also ruptured what had been close links between Erdogan and

Putin, especially after Turkey shot down a

Russian jet in November 2015, leading to the death of a Russian

pilot. Relations with Saudi Arabia also temporarily frayed on Syria because of

Turkey’s closeness to the Muslim Brotherhood, Riyadh’s enemy.

Turkey has therefore spent the past few months trying to repair some of

the damage from its Syria policy. In May, Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu was

suddenly dismissed with Erdogan’s supporters blaming the departing premier for

what were often the president’s Syria policies. Soon afterwards, alongside

improving ties with Israel and Egypt, a rapprochement with Russia was sought,

and Erdogan publicly apologized to Putin for the Russian pilot’s death.

Tensions with Washington were also eased.

These rapprochements all facilitated Turkey’s current intervention in

Syria, which would not have been possible without U.S. air cover and Russian

assurances not to respond. Washington apparently is currently ordering its

ally, the PYD-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces, to remain east of the

Euphrates, the limit of Turkey’s incursion. There were also domestic reasons

for the move. Erdogan, in his bid to change Turkey’s constitution to give

greater powers to the presidency, is courting the votes of right-wing

nationalists by portraying himself as tough on Kurdish militancy. Similarly, with the country rocked by the attempted coup

in July, a foreign campaign is a welcome distraction for an anxious public and a

military uneasy at the purges of alleged plotters currently underway.

However, this is no sign of strength. Erdogan has invaded northern Syria

after all else has failed. He could not persuade the U.S. to intervene against

Assad and proved unable to help forge a united and effective rebel force to

overthrow the Syrian dictator. Instead he has had to send in Turkish troops

directly, not to achieve his initial goal in Syria from 2011, toppling Assad,

but to deal with new problems, ISIS and the PYD, that emerged partly as a

result of his own policies. Moreover, with no clear exit strategy outlined,

this move could yet turn into a quagmire and another costly Turkish failure on

Syria.

For updates

click homepage here