A few days ago

Foreign Policy published an article suggesting that Beijing Is Shooting Its Own

Foot in Hong Kong Political paranoia is making it hard for the Chinese

Communist Party to sell its own narrative, today China freed a British

consulate worker whose detention only helped to fuel tension.

Last night, a

human chain stretched for kilometres across both

sides of Hong Kong harbour as people turned out for a

peaceful demonstration inspired by anti-Soviet protesters in Estonia, Latvia

and Lithuania in 1989 that became known as the Baltic Way (also

pictured on).

It is worthwhile

however to look at this in a larger context of what is happening with mainland

China as a whole while expanding on my earlier observations about the development of China's new nationalism.

Some of the

observations that can be made about about China today

is that the country has just experienced a period of economic growth the likes

of which the world had never before seen to which we can ad that China is

ruled, increasingly dictatorially. There are also indications that the party

wants to bring private enterprise to heel, by intervening more directly in how

businesses are run.

Behind these policies

lies a growing insistence that China’s model of development is superior to the

West’s. Thus in the above-quoted speech, Xi claimed that “the Chinese nation, with

an entirely new posture, now stands tall and firm in the East.”

Hong Kong in the light of chinese

nationalism

The report 0n 29 July

about a mainland Chinese man pushing a female Hong Kong overseas student to the

ground at the University of Auckland in New Zealand may seem inconspicuous on

its own. But it’s a worrying sign of how Beijing has turned Hong Kong’s

protests into an interethnic conflict, one that could flare into worse

violence.

Also by putting a heavy

emphasis on the discolored national emblem through state-controlled media,

the Chinese government is deliberately whipping up nationalist fervor among

mainland Chinese citizens and is granting license for people to act against

imagined enemies of China. This form of political

and psychological

warfare has the potential to lead to even greater tragedy than a

conventional military crackdown, as it could poison the relationship between

Hong Kongers and mainland Chinese citizens.

Hong Kong students

abroad have described an atmosphere of fear, intimidation and vitriol in

dealing with ultra-nationalistic mainland Chinese since the city’s

anti-government protests broke out.

For example in

Vancouver Canadian police needed to escort worshippers as ‘bullying’ pro-China

protesters surround church holding prayers for Hong Kong:

Chris Chiu said the

incident had left him shaken and fearing for the worshippers’ safety. “There

were VPD [Vancouver Police Department] outside warding off people from the

area, there were people waving Chinese flags,” Chiu said. “They

were obviously here trying to intimidate us.”

Elsewhere in Melbourne

fights broke out, where

a pro-Beijing demonstrator attacked an ABC reporter.

An article in the NYT

titled Chinese

Nationalists Bring Threat of Violence to Australia Universities describes

Chinese nationalist attacked an abcnews journalist in

Melbourne. The pro-Hong Kong rally turned violent as hundreds of demonstrators

clashed with more than 100 pro-China protesters. Four MPs have voiced concerns

about the

influence the Chinese government has. And as is exemplified by the above

cited NYT article in the case of organizing pro-Beijing rallies the focus has

often been on Chinese Nationalist outfits like the worldwide

Confucius Institutes.

China's new nationalism

is the particular view of history endorsed by the Chinese leadership, which

sees the history of China from the mid-nineteenth century to the Communists’

coming to power in 1949 as an endless series of humiliations at the hands of

foreign powers. While there is some truth to this version of events, the CCP

also makes the frightening claim that the party itself is the only thing

standing between the Chinese and further exploitation. Since it would be

untenable for the party to argue that the country needs dictatorship because

the Chinese are singularly unsuited to governing themselves, it must claim that

the centralization of power in the party’s hands is necessary for protection

against abuse by foreigners.

Another troubling

aspect of nationalism in China today is that the country is a de facto empire

that tries to behave as if it were a nation-state. More than 40 percent of

China’s territory, Inner Mongolia, Tibet, Xinjiang, was originally populated by people who do

not see themselves as Chinese. Although the Chinese government grants special

rights to these “minority nationalities,”

their homelands have been subsumed into a new concept of a Chinese nation and

have gradually been taken over by the 98 percent of the population who are

ethnically Chinese (or Han, even this refers to

an earlier very different empire). Those who resist end up in prison camps,

just as did those who argued for real self-government within the Soviet empire.

Externally, the

Chinese government sustains a dystopia, next door in North Korea, and routinely

menaces its neighbors, including the democratic government in Taiwan, which

Beijing views as a breakaway province. Much of this is not to China’s advantage

politically or diplomatically. Its militarization of

faraway islets in the South China Sea, its contest

with Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, and its attempts at punishing

South Korea over the acquisition of advanced missile defenses from the United

States have all backfired: East Asia is much warier of Chinese aims today than

it was a decade ago. (The percentage of South Koreans, for example, who viewed

China’s rise favorably fell from 66 percent in 2002 to 34 percent in 2017,

according to the Pew Research Center.) Despite this dip in China’s popularity,

people across the region overwhelmingly believe that China will be the

predominant regional power in the future and that they had better get ready.

As for Hong Kong, the

economist recently spotted Chinese new nationalism in its

dismay on Weibo and WeChat even in reference to certain Western brands.

Whereby entertainers such as Liu

Yifei and Jackie Chan also took nationalist positions vis a vis the Hong

Kong protests.

Meanwhile the brief

respite from violence has come to an end today, with

police firing tear gas at demonstrators as the city's protests enter their

12th weekend. Protesters took to Kwun Tong district in the city's east on

Saturday, reiterating the

five demands that have emerged during this pro-democracy movement, and

adding an additional issue: the government's installation

of "smart" environmental monitoring lampposts, which have sparked

privacy concerns. The protest movement still appears to have broad support,

with thousands, including families, lawyers, accountants and young and old

people, taking to the streets in anti-government rallies today.

There are more protest scheduled for tomorrow, Sunday.

As to how all of this

will end, it is unclear what will happen but while the Hong Kong Government so

far has denied this 'will' happen, there is still 'some' possibility that Beijing at one point could cite Article 18 of the

basic law, which permits the National People's Congress to impose a curfew

if the Hong Kong government cannot restore order, arguing that the right to

impose a curfew implies the right to police a curfew. If it did, however, local

police would probably be in command of any People's Armed Police forces.

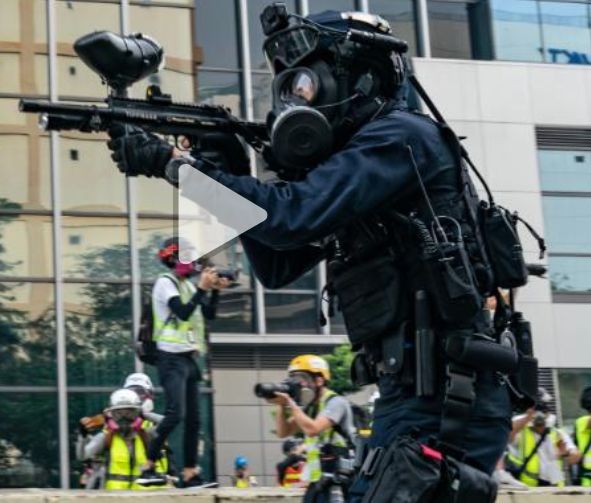

With policeman who

are dressed like the are part of a military style war and demonstrators who

before they as always retreat attempt at times to fight back today is another

day that is leading to escalation.

Update 29

Aug. 2019: The rotation of

fresh Chinese military troops to the Hong Kong garrison sparked widespread

concern Thursday, demonstrating how on edge the city is ahead of a thirteenth

consecutive weekend of anti-government

protests. In a statement, China's military said the "annual normal

routine action" had been carried out with the approval of the Central

Military Commission and the troops would "resolutely safeguard national

sovereignty, security, and development interests, effectively perform Hong

Kong's defense duties, and safeguard Hong Kong's prosperity."

The People's

Liberation Army troop movements were carried out in the dead of the night,

and took place at the same time as a rotation of the garrison in neighboring

Macao. They were announced

by Chinese state media early Thursday morning. The move also came as Chief

Executive Carrie Lam would

not rule out using emergency powers-- which would give her the right to

pass new laws without the approval of legislators, if violent protests

continue.

Police have denied

permission for a major protest planned by the Civil Human Rights Front on

Saturday. The CHRF previously organized three peaceful marches it said

attracted more than a million participants. Organizers said they are appealing

the police decision. While fears about a military crackdown have often focused

on visions of PLA tanks crossing the border, the military has had a major

presence in Hong Kong since the city was handed over from British to Chinese

control in 1997.

The 6,000-strong

garrison largely

avoids public view, however, aside from displays to mark key anniversaries

or the visits of Chinese officials, such as when President Xi Jinping inspected

troops in 2017 to mark 20 years of rule from Beijing. Under the city's

constitution, the Hong Kong government can request the assistance of the

garrison "in the maintenance of public order and in disaster relief."

Administration and

police officials have repeatedly denied any need to call on the military, even

as the protests have taken an increasingly violent turn. This has not stopped

the rampant concern that a crackdown could come at some point, which has been boosted

by a large

buildup of paramilitary forces across the border in Shenzhen.

While most analysts

agree that the presence in the Chinese city of the People's Armed Police, a

force under the military commission, is likely intended to send a message to

domestic audiences that the government is in control and will not allow unrest

to spill over the border, it has caused concern among many in Hong Kong. Lam's

apparent suggestion that she could invoke emergency powers has deepened that

concern. Police resources have been stretched by the months-long protests, and

were the government to institute a curfew or other radical action that such a

move would allow, it's likely they would require reinforcement, potentially

from the military.

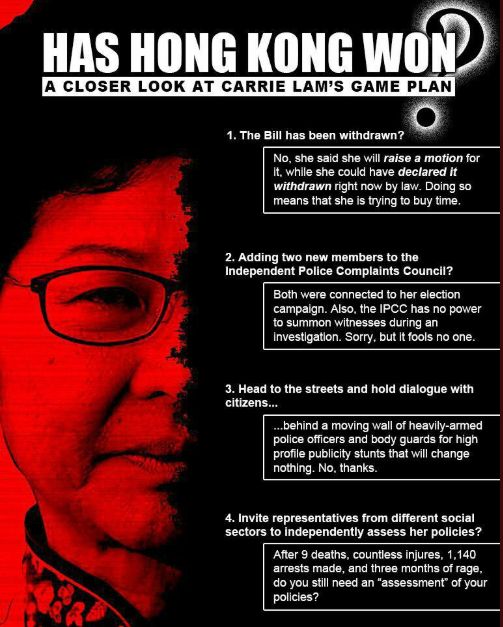

Today a poster was circulated illustrating what the

protesters are thinking:

For updates click homepage here