By Eric Vandenbroeck

As I suggested in a 2012 article, little

attention had been given to sovereignty in the South China Sea until the 1960s

and 1970s, when international oil companies began prospecting in the region.

Except that, Washington didn’t artificially build the Hawaiian islands. With

its recent reference to Hawaii (Pear Harbor) however, and

having moved surface-to-air missiles over to one of the islands, there is no

doubt that China is currently militarizing the situation.

Though this standoff might seem like simple nationalist posturing

between two Pacific powers, maritime disputes carry a special significance in

Asia. Unlike in Europe, water is the organizing element of the continent, which

wraps around the East and South China Seas, the Bay of Bengal and Indian Ocean,

as well as countless peripheral lagoons and bays. Ownership of a particular

island, reef or rock, and the right to name a body of water is more than a

question of sentimentality, it is the foundation of many national policy

strategies. Securing the right to patrol, build bases and regulate trade

through these waterways can mean access to resources critical to sustaining

economic growth and political stability.

Pacific Rivals

Beijing’s and Washington’s divergent perspectives are rooted in

radically different national and regional strategies. On the world stage, China

portrays the South China Sea dispute as fundamentally a question of

sovereignty. The United States, however, foregrounds concerns about freedom of

navigation. Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has been the

unquestioned pre-eminent power in the Pacific Rim, assisted by its allies, most

notably Japan and South Korea. Simultaneously, however, China has been emerging

as a potential regional hegemon, and the South China Sea has become the most

visible area of tension.

One of the current risks is a potential clash caused by China’s

paramilitary ships that could bring U.S. forces to bear in defense of U.S.

allies.

Who claims what?

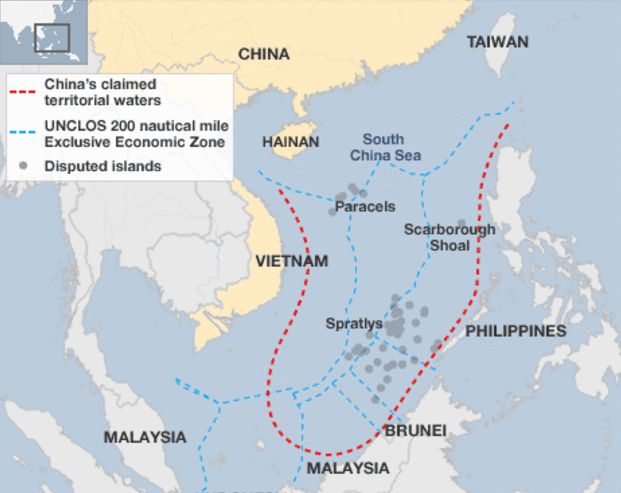

China claims by far the largest portion of territory - an area defined

by the "nine-dash line" which stretches hundreds of miles south and

east from its most southerly province of Hainan.

Beijing says its right to the area goes back centuries to when the

Paracel and Spratly island chains were regarded as integral parts of the

Chinese nation. Those claims are mirrored by Taiwan.

Vietnam hotly disputes China's historical account, saying China had

never claimed sovereignty over the islands before the 1940s. Vietnam says it

has actively ruled over both the Paracels and the Spratlys since the 17th

Century - and has the documents to prove it.

The other major claimant in the area is the Philippines, which invokes

its geographical proximity to the Spratly Islands as the main basis of its

claim for part of the grouping.

Both the Philippines and China lay claim to the Scarborough Shoal (known

as Huangyan Island in China) - a little more than 100 miles (160km) from the

Philippines and 500 miles from China.

Based on Res nullius, however, the Philippines

have the strongest argument.

In 1971, the Philippines officially claimed 8 islands that it refers to

as the Kalayaan islands, arguing that: 1. the Kelayaan were not part of the

Spratly Islands, and 2. the Kelayaan had not belonged to any country and were

open to being claimed. In 1972, these islands were designated as part of the

Palawan Province, and it has a mayor and local government to see to the needs

of its 222 inhabitants. The features consist of six islets, two cays, and two

reefs. The latter arguments are based on customary law, res nullius, 27 Shen

Jianmen. South China Sea Dispute. pg 144 24 which states that that there must

be both abandonment of possession and the intent to abandon; one condition

without the other being insufficient.28 Due to the absence of any claim by any

country at the time, the Philippines claimed the area. In the late 1970s when

hydrocarbons were discovered, other countries began to espouse their claims.

However, based on res nullius the Philippines have the strongest argument.

Recent flashpoints

- In early 2012, China and the

Philippines engaged in a lengthy maritime stand-off, accusing each other of

intrusions in the Scarborough Shoal.

- In July 2012, China angered

Vietnam and the Philippines when it formally created Sansha city, an

administrative body with its headquarters in the Paracels which it says

oversees Chinese territory in the South China Sea.

- Unverified claims that the

Chinese navy sabotaged two Vietnamese exploration operations in late 2012 led

to large anti-China protests on Vietnam’s streets.

- In January 2013, Manila said it

was taking China to a UN tribunal under the auspices of the UN Convention on

the Laws of the Sea, to challenge its claims.

- In May 2014, the introduction

by China of a drilling rig into waters near the

Paracel Islands led to multiple collisions between Vietnamese and

Chinese ships.

- In April 2015, satellite images

showed China building an airstrip on reclaimed land in the Spratlys.

- In October 2015, the US sailed a guided-missile destroyer within 12-nautical

miles of the artificial islands – the first in a series of actions planned to

assert freedom of navigation in the region.

The decision by the Permanent Court of arbitrations ruling on the issue

of its jurisdiction in the Philippines’ case against China is expected by June 2016.

What the Philippines wants

from the tribunal

The Philippines has asked the tribunal to rule on the validity of

China’s claim to territory that falls within what China calls the “nine-dash

line,” a U-shaped area of demarcation dipping far off the mainland’s southern

coast, sweeping east of Vietnam, down near Malaysia and Brunei, and then

looping back up west of the main Philippine islands. The loop encompasses the

Paracel and Spratley islands and Scarborough Shoal.

Though China has never explicitly defined what privileges it believes it

has within the nine-dash line, it has asserted “historic rights” in the

area.

The Philippines worries that such a claim could eventually lead China to

assert full sovereignty and control over all the land, water, seabed and other

atolls and shoals within its boundaries.

A less expansive interpretation might regard the nine-dash line as a

'box' in which China has sovereignty over certain islets and jurisdiction of

their corresponding maritime zones. This is the difference between claiming

that the South China Sea is an internal Chinese lake or saying that China has

some outlying islands off its coast which generate maritime zones. In the

latter case, the waters between the Chinese mainland and the islands are

international for the purposes of military and civilian naval traffic.

Why the Philippines took this

step

The Philippines said it filed the claim in 2013 to protect its national

territory and maritime domain, describing the dispute as a matter of “our patrimony, territory, national

interest and national honor.” It said that China has been damaging the marine environment

by destroying coral reefs, engaging in destructive fishing practices and

harvesting endangered species.

China has engaged in massive land reclamation efforts in the region,

expanding rocky outcroppings into landing strips and other facilities that

could have military uses. Manila asserts that China’s moves “cannot

lawfully change the original nature and character of these features.” These

small features, the Philippines contends, are not entitled to any “exclusion

zones” extending beyond 12 miles that would limit fishing and other activities

by other countries. (The U.S. Navy shares this position and recently sailed

ships through the region to emphasize the point.)

In a Q&A outlining its rationale for bringing the case, the

Philippines Foreign Ministry said it had exhausted “all possible initiatives.”

It urged China to participate in the tribunal’s proceedings, saying: “China is

a good friend. Arbitration is a peaceful and amicable process to settle a

dispute between and among friends.”

The U.S. has backed Manila’s pursuit of the case.

If China is going to ignore the ruling, is this all pointless?

Although China has turned its back on the tribunal, refusing to

participate in any of the proceedings, the ruling could have significant

consequences for regional and international relations. It could further ratchet

up tensions, or cool things down.

If Manila prevails, that could encourage other nations to pursue similar

cases or use the ruling as a basis to more strongly challenge Chinese behavior

around islets and in waters that are in dispute.

A more mixed ruling might undercut faith in international dispute

resolution mechanisms such as the tribunal and the agreements that underpin

them. That could lead to moves by regional players or the United States to step

up freedom of navigation exercises and other activities such as fishing or

drilling for oil in the region.

Some analysts say China could change its tune if the tribunal rules

strongly against it.

Until recently Indonesia has been immune to the hostilities of the South

China Seas. Instead, Indonesia has been an honest broker among the disputing

neighboring states: China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and

Taiwan. On June 23, 2014, however, a Chinese publishing company had redrawn

China’s territorial boundary of the South China Sea from the former nine

dash-lines and transformed it to the “ten dash-lines.”

China has a policy of “no specification of its claims” in the South

China Sea.China’s actions indicate that it has claimed sovereignty over the

entire South China Sea, but at the same time, it refuses to particularize or

justify its claim aside from the historical nine-dashed-line map that it has

produced.

Meanwhile, China is also determined to consolidate and control its

claimed areas as a drive to re-establish itself as the dominant power in Asia.

Should China lose its claims in the South China Sea to smaller States, this

could severely damage its legitimacy as a main power player in the region. At

the same time, its losses would exacerbate other contentious regions in the

country, i.e.Tibet, the Uighur provinces, the Taiwan

issue and the recent democratic movement in Hong Kong.

China claims the sovereignty over four chains of islands: the Paracel

Islands, the Spratly Islands, Pratas Islands, and the Macclesfield Bank in the

South China Sea. China deemed that the Pratas Island chain of Islands and the

Macclesfield Bank as less controversial and relatively unimportant. The dispute

between the two areas has not had any significant impact on international

relations; accordingly the value of the Pratas and the Macclesfield Bank is

limited. The Pratas is much closer to China, and the Macclesfield Bank is a

totally submerged atoll. Thus, it is questionable if what lies underwater may

be owned.

A core but often unstated component of U.S. national strategy is to

maintain global superiority at sea. By controlling the seas, the United States

can guarantee the secure movement of U.S. goods and deploy military power

worldwide. This preserves global economic activity, feeding the domestic

economy, while ensuring that any threat to national security is addressed

abroad before it can reach the homeland. This state of affairs is enforced by

the powerful U.S. Navy, but it is undergirded by Washington's particular

interpretation of international law.

In China's near seas, the U.S. global imperative comes into conflict

with China's emerging regional needs. Since the early 1980s, China has

undergone a transition from an insular, self-sufficient pariah state to a major

exporter. This has forced Beijing to reassess its maritime risks and

vulnerabilities. China is no longer able to protect its national economy

without securing the maritime routes it needs to maintain trade and to feed its

industrial plant.

China's construction projects on several South China Sea reefs and

islets have stirred the ire of its Southeast Asian neighbors.

The Philippines has borne the brunt of China's expansion, and much of the

Chinese construction has been on islands Manila claims. Manila's status as an

ally risks drawing the United States into the conflict, but Washington, while

supporting Philippine security, maintains that it takes no side in competing

South China Sea claims or, for that matter, any disputes in maritime Asia.

Rather, Washington justifies its concern about the South China Sea as simply

the above-mentioned defense of the right to freedom of navigation. This freedom

includes the regular and irregular patrols of U.S. ships, submarines and air

assets within the 200-mile exclusive economic zones of other states, although

not within the 12-nautical-mile territorial seas.

China feels it can manage the opposition from various members of the

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) by both manipulating ASEAN as a

whole and by leveraging economic and military influence. Beijing also believes

it can manage Washington, betting that the United States will work to avoid any

real conflict with China in the South China Sea. This has been the case so far.

Although Washington has challenged Beijing’s take on what is and is not allowed

in the waters of the South China Sea. And whether China has a legitimate claim

to the seas there, it has been careful to avoid any action that could lead to

physical confrontation. China is well aware of U.S. reluctance to escalate the

conflict and takes advantage of it to keep expanding its presence.

Rising Sun

But Beijing does fear one thing in the South China Sea: the involvement of Japan. Tokyo, long a passive power

in the Pacific Rim, is now embarking on the long process of reasserting itself.

If Japan decides to become more involved in the South China Sea, China’s

strategy will become significantly more complicated. Recent signs indicate this

may be starting. Tokyo recently carried out search-and-rescue drills with the

Philippines, as well as other exercises with Southeast Asian states, flying an

EP3 out of Palawan over parts of the South China Sea. Japan is also negotiating

a visiting forces agreement with Manila to allow Japanese ships and planes to

refuel and resupply in the Philippines. It is also offering to fund and supply

ships and aircraft to the Philippine and Vietnamese coast guards and navies.

And Tokyo and the United States have agreed in principle to carry out joint

patrols in the South China Sea, perhaps as early as next year.

Japan has its own concerns about South China Sea claims. As an island

nation with few natural resources, Japan’s economic lifelines can only pass

through the seas, it has no land options. China’s expansion of activity in the

waters, following its assertive activities in the East China Sea, have made it

clear to Tokyo that there has been a real change in the Asia-Pacific and that

Japan needs to secure its interests. While China has suggested it may accept

continued U.S. patrols, it has also asserted that it absolutely cannot accept

any role for Japan in the South China Sea, arguing that Japan has no legitimate

claims or interests in the waters.

China’s kneejerk response against Japan is in part conditioned by

Tokyo’s history of belligerent imperialism. More concretely, however, Beijing

recognizes that Japan will have a freer hand in the Pacific than the globally

committed United States. The United State is further limited because it, like

China, is a nuclear power. Japan is not. This places a stopgap on escalation

similar to the constraint on the United States and the Soviet Union during the

Cold War. This also explains why Beijing has been so set against potential U.S.

deployment of Terminal High Altitude Area Defense anti-ballistic missile

systems in South Korea. This system would give U.S. missile defense reach onto

the Asian mainland and, over time, potentially weaken the viability of a Chinese

nuclear counterstrike capability.

China has pledged to not use nuclear weapons against a non-nuclear

state. If Beijing intends to uphold that pledge, its ability to threaten Japan

is diminished. All of this adds up to a greater threat if Japan and the United

States align in the South China Sea. A combined Japanese-U.S. force would be a

far different challenge for China than any single force. China is now trying

through numerous channels to make clear to the United States that Japan does

not have the same constraints and may be willing to gamble with the U.S.

security for its own interests. And Japanese aid to the Philippines, by

extension, would embolden Manila to potentially trigger a short, sharp clash

with China on a disputed islet, armed by Tokyo and able to rely on Washington

to step in if things escalate.

For update

click homepage here