Few events have

transformed the course of human history more swiftly and profoundly than the expansion of

early Islam.

We earlier covered

the Shi’ite-Suni devide in context of the history of Iran, and separatly, by focussing on devellopments in Islam as of the 15th century.

In brief however,

Islam's shism began in A.D. 632, immediately after

the Prophet Muhammad died without naming a successor as leader of the new

Muslim flock. Some of his followers believed the role of Caliph, or viceroy of

God, should be passed down Muhammad's bloodline, starting with his cousin and

son-in-law, Ali ibn Abi Talib. But the majority backed the Prophet's friend Abu

Bakr, who duly became Caliph. The effects of electing 'Abu Bakr over 'Ali were

felt in other ways that would contribute to the emergence of squabbling

divisions within Islam. Ali thus would eventually become the fourth

Caliph before being murdered in A.D. 661 by a heretic near Kufa, now in Iraq.

The succession was once again disputed, and this time it led to a formal split.

The majority backed the claim of Mu'awiyah, Governor of Syria, and his son

Yazid. Ali's supporters, who would eventually be known collectively as Shi'at Ali, or partisans of Ali, agitated for his son

Hussein. When the two sides met on a battlefield near modern Karbala on Oct.

10, 680, Hussein was killed and decapitated. But rather than nipping the

Shi'ite movement in the bud, his death gave it a martyr. The annual

mourning of Hussein's death, known as Ashura, is the most poignant and

spectacular of Shi'ite ceremonies: the faithful march in the streets, beating

their chests and crying in sorrow. The extremely devout flagellate themselves

with swords and whips.

Those loyal to

Mu'awiyah and his successors

as Caliph would eventually be known as Sunnis, meaning followers of the Sunnah,

or Way, of the Prophet. Since the Caliph was often the political head of the

Islamic empire as well as its religious leader, imperial patronage helped make

Sunni Islam the dominant sect. Today about 90% of Muslims worldwide are Sunnis.

But Shi'ism would always attract some of those who felt oppressed by the

empire. Shi'ites continued to venerate the Imams, or the descendants of the

Prophet, until the 12th Imam, Mohammed al-Mahdi (the Guided One), who disappeared in the 9th

century at the location of the Samarra shrine in Iraq. Mainstream Shi'ites

believe that al-Mahdi is mystically hidden and will emerge on an unspecified date to usher in a reign of

justice.

Shi'ites soon formed

the majority in the areas that would become the modern states of Iraq, Iran,

Bahrain and Azerbaijan. There are also significant Shi'ite minorities in other

Muslim states, including Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and Pakistan. Crucially, Shi'ites

outnumber Sunnis in the Middle East's major oil-producing regions--not only

Iran and Iraq but also eastern Saudi Arabia. But outside Iran, Sunnis have

historically had a lock on political power, even where Shi'ites have the

numerical advantage. (The one place where the opposite holds true is modern

Syria, which is mostly Sunni but since 1970 has been ruled by a small Shi'ite

subsect known as the Alawites.) Sunni rulers maintained their monopoly on power

by excluding Shi'ites from the military and bureaucracy; for much of Islamic

history, a ruling Sunni élite treated Shi'ites as an underclass, limited to

manual labor and denied a fair share of state resources.

Sunni Caliphs in

Baghdad tolerated and sometimes contributed to the development of Najaf and

Karbala as the most important centers of Shi'ite learning. Shi'ite ayatullahs, as long as they refrained from open defiance of

the ruling élite, could run seminaries and collect tithes from their followers.

The shrines of Shi'ite Imams in Najaf, Karbala, Samarra and Khadamiya

were allowed to become magnets for pilgrimage.

Sectarian relations

worsened in the 16th century. By then the seat of Sunni power had moved to

Istanbul. When the Turkish Sunni Ottomans fought a series of wars with the Shi'ite Safavids of Persia, the Arabs caught in between were sometimes obliged to

take sides. Sectarian suspicions planted then have never fully subsided, and

Sunni Arabs still pejoratively label Shi'ites as "Persians" or

"Safavis." The Ottomans eventually won control of the Arab

territories and cemented Sunni dominance.

In 1979, Khomeini

after returning from Exile, joined the movement that exploded in the streets of

Iran, which aimed at overthrowing the Shah of Iran. After the Shah fled,

Khomeini took power as a result of Iranian revolutionary students seizing the

U.S. embassy in Tehran, making hostages of the diplomats that were there. It

was this coup and power struggle that eventually ended up in the hands of a new

Shiite government in Iran, that emboldened the Shia across the entire Islamic

World. This would be the first sign of activism within Shiism that continues to

this day.

Shortly thereafter,

the word of Khomeini’s revolution spread to Lebanon, where Israel had ousted

the PLO (Palestinian Liberation Organization) where it was

mounting Guerrilla attacks against Israel. After ousting the PLO from Lebanon,

a new radical islamic group was created known as Hezbollah.

As part of a

concerted effort across the middle east to resist Khomeini’s ideologies by the

Sunni, Sunni governments across the middle east reacted denouncing it as a

model for their own societies through aggressive campaigns, none more

aggressive than Saddam Hussein. In 1980, Saddam invaded Iran, toppling the

Persians as he referred to them, in an effort to seize Iranian oil fields. This

invasion of Iran by Saddam created once more a Deeper divide between the Sunni

and Shiites. in Islam.

The Iran-Iraq war

ended in 1988 following Iraq’s widespread use of chemical weapons. Peace lasted

in the middle east for only two years, interrupted by Iraq’s new invasion of

Kuwait, bringing the United States in a lasting war in the middle east against Iraq,

eventually leading to its invasion and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, his

arrest, and eventual execution.

Following the

invasion of Kuwait, the United States responded with over half a million

troops, ousting Iraq’s army from Kuwait. The Shia in Iraq had at this point had

enough with Saddam’s regime, rising up against him.

With a brutal response, Saddam quickly squashed the

rebellion.

No one came to the

Shiites aid in what ended up to be a very brutal campaign waged by Saddam

against the Shiites. Not neighboring Saudi Arabia, not the United States, which

called for the rebellion. No one assisted the Shiites but neighboring Iran. As

a response to the uprising, in 1990, Saddam launched a systematic murder

campaign killing ten shiite ayotollahs

and their families.

As a result to

Saddam’s Iraqi and Arab nationalism, the Shiites of Iraq became more religious

and more sectarian in their views, creating forces of Muslim sectarianism ever

unseen in the Middle East that was unleashed by the USled

invasion of

Iraq in 2003.

Iran and the Shiites Protest in Saudi-Arabia Today

While the Saudi

authorities are still trying to make sense of the unrest, the kingdom’s most

prominent Shiite cleric, Sheikh Hassan al-Saffar, issued a statement calling

for the end of anti-Shiite actions by the authorities. As much as 15 percent to

20 percent of Saudi Arabia’s population belongs to the Shiite sect. The Sunni

majority, which adheres to the ultraconservative Wahhabi school of thought,

largely considers the Shia to be heretics. Despite this religious schism, the

kingdom has for the most part remained free of any serious Shiite unrest.

The largest

occurrence of sectarian violence in the kingdom took place in 1987, when Saudi

security forces killed 400 Shiite protesters (a majority of whom were believed

to be Iranian nationals) in an attempt to control an unauthorized demonstration

in the holy city of Mecca. Since the founding of the Islamic Republic of Iran

during the 1979 revolution, the Saudis have feared that Tehran would use the

kingdom’s Shiite minority to undermine the Saudi state and enhance Iranian

influence — a fear magnified by the fact that the Shia are concentrated in

Saudi Arabia’s oil-rich Eastern Province along the Persian Gulf. Until the 2003

U.S. invasion of Iraq and the subsequent regime change in Baghdad, the Saudis

took comfort from the fact that the Baathist regime in Iraq served as a bulwark

against Iranian/Shiite expansionism across the Persian Gulf.

When Baathist Iraq

was replaced by a Shia-dominated regime heavily influenced by Tehran, the

Saudis’ worst nightmare was revived. One way the Saudis have been trying to

deal with the fear that the kingdom’s Shiite minority could become an Iranian

fifth column is by co-opting the Shia — part and parcel of Saudi King

Abdullah’s strategic plans for reform.

Saudi Arabia’s

monarch, King Abdullah, on Feb. 14

effected a shake-up of his

government, including the replacement of the head of the country’s powerful

religious police and a controversial senior judicial figure, as well as the

appointment of the kingdom’s first-ever female Cabinet member.

While the reforms

were instituted to deal with jihadists and the larger problem of religious

extremism, one of the unintended consequences of the reform project is that it

has provided the space for the Saudi Shia to advance their communal interests.

The Saudi Shia are encouraged not only by the opening up at home, but also by

the regional climate, in which Iran is the vanguard of the Shia’s struggle to

assert themselves. However, the reforms in Saudi Arabia have created the

possibility of backlash against Riyadh from elements within the Wahhabi

religious establishment who do not like losing their influence amid the social

changes.

An assertive Shiite

minority acts as salt on the wounds of the hard-line

Wahhabis. This increases the probability of sectarian violence in the kingdom,

which can be exploited by both Sunni and Shiite opponents of the regime. It is

unclear whether the Iranians were behind the recent disturbances, but they are

certainly going to try to exploit them to their advantage. For the Saudis, the

Shiite unrest complicates matters both at home, where the royal family is

already having a hard time managing change, and in the region, where it is

trying to contain an emergent Iran.

With the United

States drawing down its presence in Iraq and flirting with the idea of

diplomatically re-engaging Tehran, the Saudis are feeling an urgency to build

up their defenses against Iran. One way to do this is through cold, hard cash.

Despite global economic turmoil and the falling price of oil, the Saudis still

have plenty of petrodollars to cushion themselves and prop up Sunni political

and militant forces to hedge against Iran and its Shiite proxies.

The second way is

through a diplomatic offensive. We have long been monitoring the warming

relations between the Saudis and the Syrians, as Riyadh has been looking for

ways to bring Damascus back into the Arab fold and deprive Iran of a key ally

in the Levant. Syria is being careful to balance its relationship with Iran by

engaging in some intelligence-sharing with the Saudis and the United States,

but a flurry of diplomatic visits between Riyadh and Damascus, including an

upcoming trip by Syrian President Bashar al Assad to Saudi Arabia, is revealing

of the progress made so far in this gradual Syrian-Saudi rapprochement. In

addition, the Saudis have been very active lately in trying to patch up

long-standing differences between Egypt and Qatar, another bid to bring Arab

states together.

Egypt, meanwhile,

appears to have its own plans for strengthening Arab unity. Egyptian

President Hosni Mubarak recently made an offer to Bahraini King Hamad bin Isa

al-Khalifa to send Egyptian combat units to the island country to defend it

against Iranian encroachment. This idea was originally proposed by Saudi King

Abdullah, who allegedly offered to cover the Egyptian troops’ expenses. Thus

the Egyptian troop presence in Bahrain would allow the leaders of the Arab

world to at least build a symbolic front against the Persian threat. Egyptian

deployments abroad are rare (the last one was during the 1991 Gulf War), and a

token troop presence in the Gulf would not stand a chance against the Iranians.

Nonetheless, there appear to be efforts under way to reignite the idea of Arab

unity, using the upcoming Arab League summit in Qatar at the end of March as a

platform to launch this agenda.

Egypt, meanwhile,

appears to have its own plans for strengthening Arab unity. Egyptian President

Hosni Mubarak recently made an offer to Bahraini King Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa

to send Egyptian combat units to the island country to defend it against Iranian

encroachment. This idea was originally proposed by Saudi King Abdullah, who

allegedly offered to cover the Egyptian troops’ expenses. This information has

not been verified, but if true, the Egyptian troop presence in Bahrain would

allow the leaders of the Arab world to at least build a symbolic front against

the Persian threat. Egyptian deployments abroad are rare (the last one was

during the 1991 Gulf War), and a token troop presence in the Gulf would not

stand a chance against the Iranians. Nonetheless, there appear to be efforts

under way to reignite the idea of Arab unity, using the upcoming Arab League

summit in Qatar at the end of March as a platform to launch this agenda.

But Arab unity has

always been a bit of a fickle idea. The Middle East is geographically spread

across the banks of the Nile, Mesopotamia and the Arabian desert. With the

exception of Mesopotamia, this land of mostly desert oases and thin coastal

strips does not allow for a dense, self-supported population that can serve as

a strong power base to unite the region. The Arab world also is a naturally

divided world of tribes, clans, religious monarchies and military

dictatorships. Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser made a historical attempt in the

1950s to create a Pan-Arab

secular nationalist movement, using the Palestinian issue as the first true

Pan-Arab cause and going so far as to temporarily unify Syria and Egypt in a

proto-United Arab Republic. But those Nasserite and Arab socialist dreams

quickly faded once Nasser was out of the picture, Israel dealt a crushing blow

to the Arabs and the geopolitical realities of each Arab regime set in.

In the present, the

Arab states can agree on the need to contain Iran, but that doesn’t mean they

will necessarily agree on a plan for going about it. Without any real military

prowess of their own, these states are still highly dependent on the United States

as their powerful backer against the Iranians. Beyond the U.S. shield, the

power of petrodollars is the Arabs’ next best defense against the Persians,

which means resource-poor countries like Egypt are left more or less on their

own.

The leading Arab

states are now taking a shot at banding together, but history and geography

dictate that the contemporary Arabs of the Middle East simply do not work well

together, even when faced with a common threat. We’ll see how these Pan-Arab

endeavors play out, but even if the Arabs can’t work together, they can still

accomplish much by working separately toward a common goal: containing their

Persian rivals.

|

23

Dec. 2016: While there is no clear

resolution in sight when it comes to settling the Israeli and Palestinian

dispute, including the governments that offer the Palestinian Authority

political and financial support, are loath to risk their relationship with

Israel by advocating the creation of a Palestinian state, another conference

is about to take place. Paris Peace

Conference redux 15 Jan.2017:

|

25

Dec. 2016: The Syrian civil war

and the Middle East going forward.

|

20 Dec. 2016: From Versailles to the

Making of the Modern Middle East P.8: British rule,

Arab Spring-revolt, and the Syria crisis today.

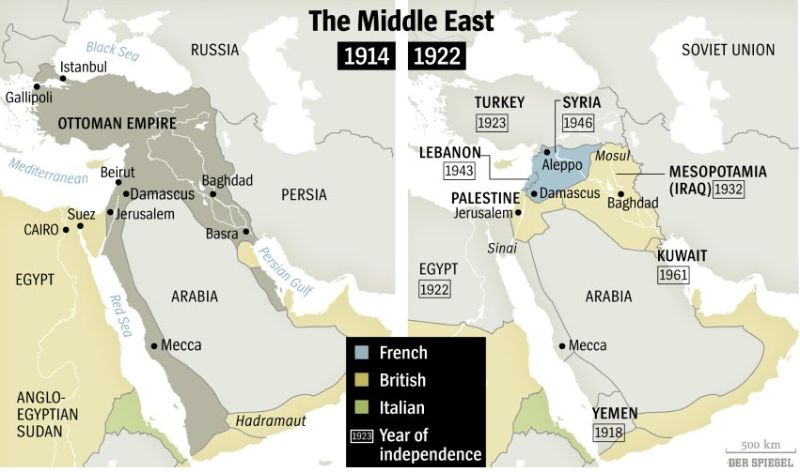

14 Dec. 2016: Sykes-Picot granted Britain the right to administer

Syria after it captured the Levant from the Ottomans in 1918.In 1919, London

conceded at the Paris Peace Conference both Levantine entities to France that

moved quickly and, aware of Hashemite progress, settled on creating Greater Lebanon.From Versailles to the Making of the Modern Middle

East P.7: The unresolved sectarian issue in Lebanon

today.

8 Dec. 2016: The profound effects of

the British Empire’s actions in the Arab World during the First World War can

be seen echoing through the history of the 20th century. From Versailles to the

Making of the Modern Middle East P.6: The importance of oil, the ‘Arab question’, and the

British.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In recent months a number of Arab States, like for example Amman, have celebrated the

centennial of the 'Arab Revolt' 1916-2016.

20 Oct. 2016: Soon I will be posting a

series of three research articles about the Balfour Declaration and several

more about the Versailles Treaty and the Making of the Modern Middle East,

whereby first here an introductory: During the First World War, British strategy

for the Middle East was aimed at protecting India, which meant keeping India’s

numerous Muslim subjects tranquil. Initially, this gained Whitehall’s support,

as it feared foreign troops in the Muslim Holy Land would make the followers of

Hussein, the Sharif of Mecca, Emir of the Hejaz and potential British ally,

oppose him. From Versailles to the Making of the Modern Middle East P.1: The

‘Arab revolt’, Britain, and the Collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle

East.

24 Oct. 2016: Mark Sykes returned to

England where, almost immediately, he was thrust into negotiations with M.

Charles François Georges-Picot, French counselor in London and former French

consul general in Beirut, to try to harmonize Anglo-French interests in ‘Turkey-in-Asia’.

Picot on the other hand had ‘expressed complete incredulity as to the projected

Arab kingdom, said that the Sheikh had no big Arab chiefs with him, that the

Arabs were incapable of combining, and that the whole scheme was visionary.'

From Versailles to the Making of the modern Middle East P.2: The Arab question and the ‘shocking document’

that shaped the Middle East.

26 Oct. 2016: The rebellion sparked by

the Hussein-McMahon correspondence; the Sykes-Picot agreement; and memoranda

such as the Balfour Declaration (to be dealt with in detail) all have shaped

the Middle East into forms which would have been unrecognizable to the diplomats

of the 19th century.From Versailles to the Making of

the modern Middle East P.3: The Menace of Jihad and How to Deal with It.

29 Oct. 2016: French rivalry in the

Hijaz; the British attempt to get the French government to recognize Britain’s

predominance on the Arabian Peninsula; the conflict between King Hussein and

Ibn Sa’ud, the Sultan of Najd; the British handling

of the French desire to take part in the administration of Palestine; as well

as the ways in which the British authorities, in London and on the spot, tried

to manage French, Syrian, Zionist and Hashemite ambitions regarding Syria and Palestine.From Versailles to the Making of the modern

Middle East P.4: The ‘Arab’ and the ‘Jewish’ question.

6 Nov. 2016: The British authorities in

Cairo, Baghdad, and London steadily lost their grip on the continuing and

deepening rivalry between Hussein and Ibn Sa’ud, in

particular regarding the possession of the desert town of Khurma.

British warnings of dire consequences if the protagonists did not hold back and

settle their differences peacefully had little or no effect. All the while the

British wanted to abolish the Sykes– Picot agreement. From Versailles to the

Making of the modern Middle East P.5: The Syrian

question.

16 Nov. 2016: This is the most important

and longest part. Following, a gripping account of the swashbuckling during the

Paris Peace Conference deliberations including the Arab/Syrian, the King-Crane

Commission, impasses and some breakthrough at the end. From Versailles to the

Making of the modern Middle East P.6: The Paris Peace

Conference deliberations.

25 Nov. 2016: One of the most

far-reaching outcomes of the First World War was the creation of Palestine,

initially under Britain as the Mandatory, out of an ill-defined area of the

southern Syrian boundary of the Ottoman Empire. Considering this, on 16 Nov.

2016, the British Parliament debated the Balfour Declaration and how its

upcoming 2017 Centennial should be handled. Yet even professionals are often

not familiar with the details surrounding the Balfour Declaration, thus here a

detailed investigation. The true history of the Balfour Declaration and its

implementations P.1.

28 Nov. 2016: Showing the topic is of

ongoing relevance, following the British Parliament last week, tomorrow a

discussion about the Balfour Declaration is to take place in the House of

Commons. My analysis, however, is wholly independent of pro or contra stance

and instead focuses on discovering the historical details that have been left

out in recent discussions. The true

history of the Balfour Declaration and its implementations P.2.

2 Dec. 2016: Apart from the strategic

consideration that they needed Palestine for the imperial defense of India, the

decision by the War Cabinet to authorized foreign secretary Balfour to make a

declaration of sympathy with Zionist aspirations in November 1917, one could

ad, was also a curious blend of sentiment (the romantic notion of the Jews

returning to their ancient lands after 1,800 years of exile) and anti-

Antisemitism (world Jewry was a force that could vitally influence the outcome

of the war) also led them to this decision.

The true history of the Balfour

Declaration and its implementations P.3.

29 November 2016 discussion about the Balfour Declaration at the

British Houses of Parliament.

5 Dec. 2016: As we have seen, in the

end, the idea was to use President Wilson’s recognition of the Balkan nations’

right to self-determination – namely, freedom from Ottoman rule – to overcome

his opposition to the implementation of this same policy in the Middle East. By

supporting Zionist aspirations in Palestine, the Lloyd George Government thus

strove to compel Wilson to expand his policy regarding the 'small nations' from

the European regions of the Ottoman Empire to its Asian territories. The true history of the Balfour Declaration and its

implementations P.4.

For updates

click homepage here