By Eric Vandenbroeck

In my comment Does the Middle East Need New

Borders? I described how the Kurdish KRG in Iraq, for all intents and purposes,

is an independent state, with its own national institutions, flag, and army.

And that Syrian Kurds, are establishing control well beyond Kurdish majority

areas in Rojava, in northern Syria.

Divided as they are among each other the wars in Iraq and Syria offered

the opportunity for Kurds in both countries to create a level of autonomy for

their areas. Thus Iraq’s Kurds were able to carve out an autonomous region

during the 1990s after the Gulf War thanks the western no fly zones. After 2003

they have more and more been talking about independence.

Kurdistan's rising

Before President Bush junior invaded Iraq I included what I titled the

(earlier) forgotten history of the Kurds. Next, as a result of the war

in Syria and Iraq in the last five years two new de facto states where produced

and enabled a third quasi-state greatly to expand its territory and power. The

two new states, though unrecognized internationally, are stronger militarily

and politically than most members of the UN. One is the Islamic State (ISIS),

which established its caliphate in eastern Syria and western Iraq in the summer

of 2014 after capturing Mosul and defeating the Iraqi army. The second is

Rojava, as the Syrian Kurds call the area they gained control of when the

Syrian army largely withdrew in 2012, and which now, thanks to a series of

victories over ISIS, stretches across northern Syria between the Tigris and

Euphrates. In Iraq, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), already highly

autonomous, took advantage of ISIS’s destruction of Baghdad’s authority in

northern Iraq to expand its territory by 40 per cent, taking over areas long

disputed between itself and Baghdad, including the Kirkuk oilfields and some

mixed Kurdish-Arab districts.

The question is whether these radical changes in the political geography

of the Middle East will persist, or to what extent they will persist, when the

present conflict is over. Turkey has been appalled to find that the Syrian

uprising of 2011, which it hoped would usher in an era of Turkish influence

spreading across the Middle East, has instead produced a Kurdish state that

controls half of the Syrian side of Turkey’s 550-mile southern border. Worse,

the ruling party in Rojava is the Democratic Union Party (PYD), which in all

but name is the Syrian branch of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), against

which Ankara has been fighting a guerrilla war since 1984. The PYD denies the

link, but in every PYD office there is a picture on the wall of the PKK’s leader,

Abdullah Ocalan, who has been in a Turkish prison since 1999. In the year since

ISIS was finally defeated in the siege of the Syrian Kurdish city of Kobani,

Rojava has expanded territorially in every direction as its leaders repeatedly

ignore Turkish threats of military action against them.

For the Kurds in Rojava and KRG territory this is a testing moment: if

the war ends their newly won power could quickly slip away. They are, after

all, only small states, the KRG has a population of about six million and

Rojava 2.2 million, surrounded by much larger ones. And their economies are

barely floating wrecks. Rojava is well organised but

blockaded on all sides and unable to sell much of its oil. Seventy per cent of

the buildings in Kobani were pulverised by US

bombing. People have fled from cities like Hasaka that are close to the

frontline. The KRG’s economic problems are grave and probably insoluble unless

there is an unexpected rise in the price of oil.

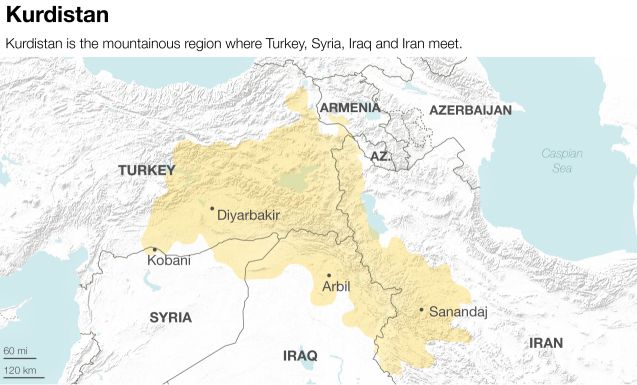

The

following map shows on the left Kurdish "Rojava" and on the right the

Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq and Syria.

The fresh ISIS offensive in early August 2014 initiated a convergence of

U.S. and Kurdish goals, as well as a change in the Kurdish pitch for support.

Backed by the US, in Kobani, for the first time, Isis was fighting an

enemy – the People’s Defence Units (YPG) and the

Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). The SDF is essentially a subsidiary of the

Kurdish YPG.

The US said tried to attract Arab rebels to ally with the YPG under the

banner of the SDF, hoping this could create a force more committed to fighting

ISIS than ousting Syrian President Bashar Assad. But most Arab rebels, who have

strong links with Turkey, are wary of joining, saying they get second-class

status to the favored Kurdish forces.

The coalition is trying to implement a plan to choke Raqqa by taking the

surrounding area, but it still needs a bigger Arab force to hold those towns.

Washington recently deployed 250 more US troops to bolster Syrian forces

fighting ISIS. The SDF’s own Arab members remain wary of efforts to encourage

more Arab groups to join the alliance.

“We are like people walking barefoot on a burning surface,” said one

commander of the Thuwar Raqqa brigade, an Arab rebel

group that is part of the SDF. “It is a forced marriage.”

The United States has been backing the YPG and such support, namely, the

promise of air support and better weapons, is essential for encouraging tribes

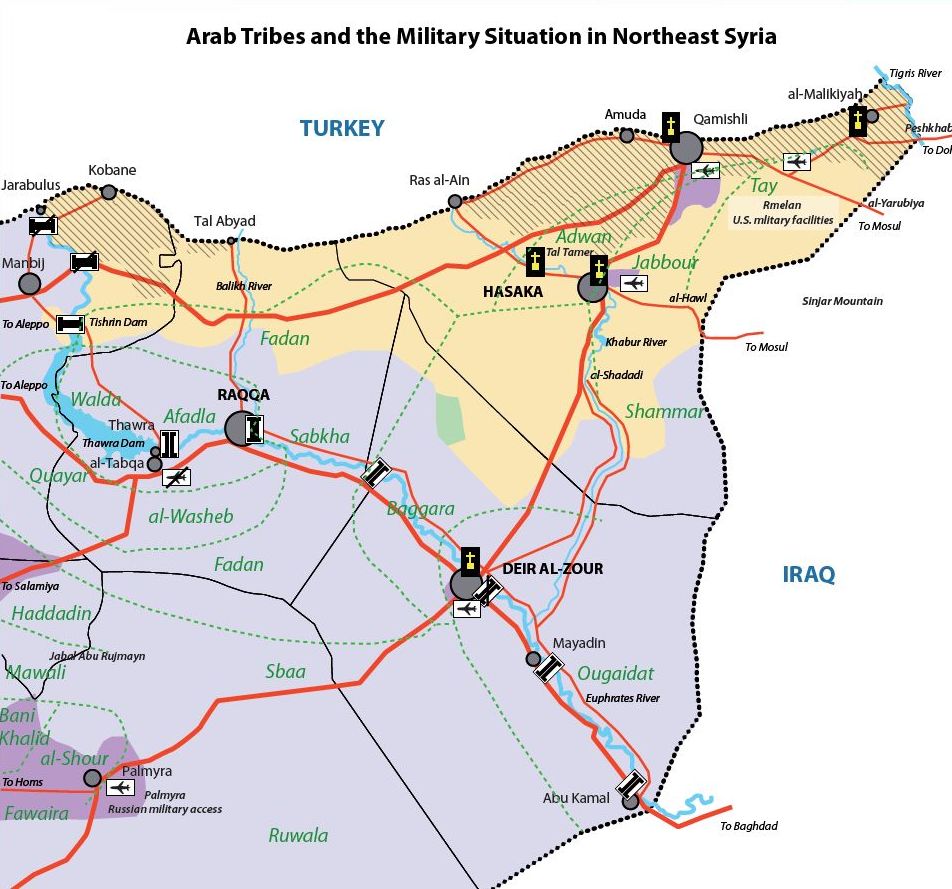

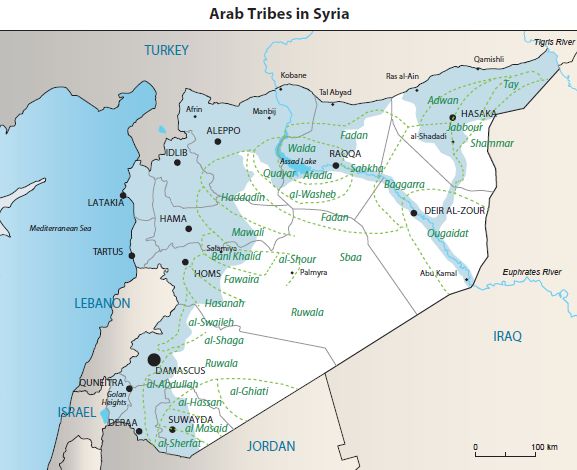

to join the anti- ISIS coalition. Arab tribes from the Fadan

federation have already joined the YPG in Raqqa province, while several Shammar tribes in Hasaka province helped YPG units capture

al-Hawl and al-Shadadi from

ISIS last winter. These tribes have always had good relations with the Kurds;

for example, they refused to help Assad repress the Kurdish uprising of 2004.

Yet they are relying on Washington to moderate the PYD's hegemonic tendencies

and ensure their own share of power once ISIS has left.

The same process is taking place in the northern part of Raqqa province,

but with many more obstacles. Some tribes remain fiercely on the Islamic

State's side (e.g., the Afadla and Sabkha), and those

who have been expelled from their lands by ISIS -backed tribes are not ready

for quick reconciliation (e.g., the Jais and Sheitat).

As a result, the SDF is reaching the limit of how many more tribes it can

integrate, and spurring a general uprising against ISIS would be very difficult

without neutral foreign troops on the ground. The level of violence has been so

high since 2011 that the traditional tribal measures of regulating it are no

longer adequate, several clans and tribes will be forced to flee to avoid

collective vengeance, such as the Tay in Jarabulus and the Sbaa in Sukhna (who

originally helped ISIS capture Palmyra).

The YPG and its Russian

Connection

In spite of Moscow’s ties to the government of Syrian President Bashar

al Assad, Russia also has been cultivating connections with Kurdish factions.

Russia’s history with the Kurds dates back to the 19th

century, when the Russian Empire recruited Kurdish tribes to its campaigns

against Eurasian rivals, the Ottoman Empire and Persia. The Russian Empire’s

successor, the Soviet Union, inherited these ties and used them to undermine

both Turkey and Iran. From 1923 to 1929, the Soviet Union operated its own

Kurdish region, the Kurdistansky Uyezd , in the

southern Caucasus and, in 1946, it helped establish the short-lived Kurdish

Republic of Mahabad in Iran. Later in the Cold War, the Soviets supported the

Marxist-Leninist Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), once again hoping to undermine

their traditional enemy, Turkey, which was by that point a NATO member.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Russia’s involvement with the Kurds

diminished but never fully ended. Today Russia is once again embroiled in power

politics in the region, and just as in the 19th century and in the

Cold War, Moscow has turned to the Kurds. Moscow has increased its ties with

the Democratic Union Party (PYD), a Syrian opposition group that advocates

Kurdish autonomy and federalism. The PYD’s armed wing, the Kurdish People’s

Protection Units, is a major player in the Syrian conflict. Although Russia

supports the Syrian government, Moscow has cultivated a relationship with the

PYD to gain leverage over Turkey, which opposes the party’s political

ambitions. In February, the PYD opened a representative office in Russia, its

first overseas branch. Russia has also openly tried to coordinate with the YPG,

hoping to defuse tension between the militant group and the al Assad

government. Moscow has even coordinated operations against Syrian rebel forces

to the benefit of both the YPG and Syrian loyalists.

More important, though, are indications that Moscow may be directly

arming its old ally, the PKK. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan accused

Russia on May 30 of doing just that, claiming that Moscow is giving

anti-aircraft weaponry to the PKK through Syrian and Iraqi territory. Moscow

has denied the allegations, but Erdogan’s accusation comes only a few weeks

after PKK fighters used an SA-18 man-portable air-defense system (MANPADS) to

shoot down a Turkish military helicopter. The downing of the helicopter was

noteworthy because it was the first known incident of Kurdish militants using

the relatively advanced weapons system, though they have used other MANPADS

before. As usual, the Russian connections to the situation are murky, SA-18s

can be found in Syria and the PKK may not have purchased them from Moscow.

Nevertheless, Russia could be using the conflict in Syria and Iraq to

strengthen its ties to the PKK, enhancing its leverage against Turkey while

maintaining plausible deniability in the process.

Ankara in turn has warned several times that if the Kurds move west towards

Afrin the Turkish army will intervene. In particular, it stipulated that the

YPG must not cross the Euphrates: this was a ‘red line’ for Turkey. But when in

December the YPG sent its Arab proxy militia, the Syrian Democratic Forces

(SDF), across the Euphrates at the Tishrin Dam, the

Turks did nothing – partly because the advance was supported at different

points by both American and Russian air strikes on ISIS targets. Turkish

objections have become increasingly frantic since the start of 2016. An article that appeared in the UK

Telegraph in June 2015 claimed that while Turkey’s aim is to establish a

buffer zone for refugees and against ISIS, the main target of the intervention

would be to prevent the emergence of a Kurdish state on Turkey’s doorstep.

On 2 February the Syrian army, backed by Russian air strikes, cut the

main road link towards Aleppo and a week later the SDF captured Menagh airbase

from the al-Qaida-affiliated al-Nusra Front, which Turkey has been accused of

covertly supporting in the past. On 14 February, Turkish artillery started

firing shells at the forces that had captured the base and demanded that they

evacuate it. The complex combination of militias, armies and ethnic groups

struggling to control this small but vital area north of Aleppo makes the

fighting there confusing even by Syrian standards. But if the opposition is cut

off from Turkey for long it will be seriously and perhaps fatally weakened. The

Sunni states, notably Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar – will have failed in their

long campaign to overthrow Bashar al-Assad. Turkey will be faced with the

prospect of a hostile PKK-run statelet along its southern flank, making it much

harder for it to quell the low-level but long-running PKK-led insurgency among

its own 17 million Kurdish minority.

The U.S.-led coalition in turn provides critical air support for this

Kurdish faction, and Washington has embedded hundreds of U.S. special

operations forces within the Syrian Democratic Forces, an anti-Islamic State

coalition dominated by the YPG. Because of the United States’ strong backing,

the PYD will be careful to prioritize its ties with Washington even as it takes

advantage of Moscow’s outreach.The PYD has already

benefited greatly from U.S. largess.

And while this offensive now will bring the Kurds to the outskirts of

Raqqa, the Kurds next may be distracted by their oft-stated goal of continuing westward toward Afrin in

order to link up their two border enclaves.

Yet the SDF’s main military patron, the United States, has another

reason to be cautious about the Raqqa timeline – before the coalition even

thinks about launching a final push on the city, it must rally the Arab tribes

in the area, some of whom have pledged allegiance to ISIS. Any such effort will

require a thorough understanding of the evolving role that tribes have played

there, first under the Assad regime and now under ISIS rule.

After establishing itself in eastern Syria during the war, ISIS quickly

integrated the tribes into its own system. Once local sheikhs pledged

allegiance to the supposed ISIS “caliph,” they were asked to marry their

daughters to high-ranking ISIS members and send their sons to fight with the

group. ISIS gave oil wells, land, and other benefits to those who voluntarily

joined it, but attacked those who resisted its hegemony.

Washington has made some concessions to Ankara by allowing the Arab

components of the Syrian Democratic Forces to spearhead the operation, but

Turkey is well aware that the YPG is very much involved in the assault.

The YPG is now positioned to reach an objective it has pursued for some

time: linking its three geographically separate northern Syrian holdings into a

single contiguous area that it calls Rojava. Of course, its success is by no

means guaranteed: U.S. support for the YPG is driven primarily by its interest

in taking down the Islamic State. The Syrian and Turkish governments, by

contrast, have a long-term strategic interest in stifling the YPG’s efforts and

containing the Kurds.

Will Turkey soon feel forced

to act?

Turkey's position in the conflict is becoming more difficult as the

fighting drags on. Ankara is in the midst of ongoing clashes with the PKK,

which operates inside Turkey and sparked a fresh round of fighting in July

2015. Now, Russia's support could reinvigorate the militant group at a time

when Turkish efforts to contain the YPG in northern Syria are in jeopardy.

Ankara knows that Washington will not hold back the Kurdish-dominated Syrian

Democratic Forces for long if it means allowing the Islamic State to survive.

Once the Syrian Democratic Forces are able to push toward Manbij, the Kurdish

goal of establishing Rojava may come closer to fruition.

With this dilemma in mind, Turkey appears to be considering a risky

alternative. With the help of the Syrian National Coalition, an opposition

group in exile, and Kurdistan Regional Government President Massoud Barzani's

Iraq-based Kurdistan Democratic Party, Ankara is reaching out to the Rojava

Peshmerga. The 3,000-strong Syrian Kurdish group is currently in exile in Iraqi

Kurdistan and has suspected links to the PYD's traditional rival, the Kurdish

National Council. For this reason, the PYD has long opposed the return of the

Rojava Peshmerga to Syria.

Many Kurds would support the Rojava Peshmerga's entry into the conflict

in northern Aleppo. If the returnees then succeed in place of the Syrian

Democratic Forces in pushing back the Islamic State, the YPG's goal of a united

(and anti-Turkey) Rojava would be thwarted. But Ankara is making a big gamble.

There is a distinct possibility that the Rojava Peshmerga may not be

enthusiastic about cooperating with Turkey against other Kurdish factions, even

those that are their rivals. And time is on the Syrian Democratic Forces' side;

after all, they are already launching offensives in northern Aleppo.

But I do not think the Rojava Peshmerga is strong enough to fights its

way back. Turkey is working with them and with Barzani. But Barzani can only do

so much because the KDP co-exists in Iraqi Kurdistan with the PUK which has a

different agenda. None of these groups is all that interested in fighting

outside of areas of Kurdish interest unless they are getting something in

return.

However, as the fighting intensifies in southern Turkey and northern

Syria, various Kurdish factions are becoming significantly more important.

These factions, in turn, will try to play rival powers off one another to

further their own interests. Ultimately, however, these powers might find that

the Kurds are not enough to meet their goals in Syria, potentially prompting

greater direct involvement by these external actors in the conflict.

How close is ISIS to defeat?

As seen above, Isis now is under attack in and around the last three big

cities it holds in Iraq and Syria, Fallujah, Mosul and Raqqa. It is likely to

lose these battles because its lightly armed if fanatical infantry, fighting

from fixed positions, cannot withstand air strikes called in by specialized

ground forces. They must choose between retreating and reverting to guerrilla

war or suffering devastating losses.

Nevertheless ISIS has the advantage that its enemies are wholly

disunited and detest each other almost as much as they hate Isis, if not more

so. Isis may be weakened, but its opponents are also fragile. The economy of

the Kurdistan Regional Government area is in ruins.

Isis is good at selecting vulnerable targets, in this case rebel groups

backed by the US and Turkey in the north of Aleppo province who control the

towns through which the rebel side of Aleppo used to be supplied. Isis fighters

has started to drive them backwards in recent days, in an attempt to gain

control over a larger section of the border and reinforcing their hold on the

fertile and heavily populated countryside of north Aleppo province.

Another of the many problems about ending the war is that many of the

players have an interest in seeing it continue. Thus Isis is a very convenient

enemy for many of those fighting it, which may be one reason why it is so

difficult to defeat.

With the beginning of separate offensives against ISIS in Fallujah and Raqqa, many analysts are

highlighting that this is the beginning of the end of ISIS, with Mosul next in

sight. However, there is one key issue with this analysis; these offensives do

nothing to address the structural failures in both Iraq and Syria that led to

ISIS’ rise. Moreover, there is no valid plan for the governance of the people

being ‘liberated’ from ISIS.

In Raqqa civilians deeply distrust the Kurdish forces, who are leading

the attack, due to what they see as Kurdish land grabs. As a result of the

march towards Raqqa it has been reported that many civilians have joined ISIS in order to stop the advances

of the Kurdish-dominated Democratic Syrian Army. If ISIS in Raqqa were to be

defeated there is no legitimate force that can manage the security in the city.

Therefore, it would either have to be managed by a force seen as occupiers,

which would lead to tit-for-tat conflict, or another extremist group/government

forces would take ISIS’ place.

Syria is nowhere near to reaching the political stage where a major

offensive against ISIS could have long-term success. Nor has there been the

development of local forces with legitimacy, as promised by coalition forces,

to take ISIS’ territory. ISIS is just one element of a large, extremely

complicated conflict involving multiple forces; the idea of defeating ISIS

without beginning to address the political and structural failures that have

led to these circumstances borders on ridiculous.

In both Iraq and Syria political solutions to address the rise of ISIS

have not been formulated. If ISIS were defeated today, Sunnis would still be

marginalized and would lack any serious form of political representation. Thus,

conflict would persist in one-way or another.

Hence, to stem inter tribal violence and chaos

after ISIS, the coalition will need to fill the political vacuum immediately.

But conducting free elections is not feasible in the near term, so the new

authorities will have to co-opt local notables to manage cities and districts

during the transition, as Gen. David Petraeus did in Mosul, Iraq, in 2003. The

question is whether this is possible without a neutral military force present.

The PYD cannot simply transplant its administrative experience from Hasaka and

Kobane to non-Kurdish cities such as Raqqa and Deir al-Zour; in fact, the group

has been accused of ethnic cleansing in the predominantly Arab town of Tal

Abyad.

The alternatives present problems as well. If Arab tribes in the

Euphrates Valley are left to organize themselves, they could easily devolve

into fighting over cities, land, and water -- especially around Thawra Dam, the key to local irrigation and power

generation. The Kurds would likely stay out of such conflicts because they have

no territorial ambitions in that area, but IS could return, perhaps under a

different name. The Syrian army is also close to both the dam and Deir al-Zour,

so Assad has not lost hope of exploiting tribal loyalties and fears to regain

control there. In short, stabilizing the Euphrates Valley post- ISIS will be a

major financial and political challenge.

As for Turkey, while Erdogan wants to establish a safe zone in Syria, Kurds and Russians oppose this idea. However the idea of creating

"safe areas" is the pretext Turkey intends to use if they send their

army into Syria. And while they can't get US support for the idea at the

moment, that could change later this or next year.

For updates

click homepage here