By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

The first time we

started to pay attention to this subject is when the British Medical Journal

Lancet came out with an investigation titled "Ticking

time bomb faced by China's aging population."

Meanwhile, in

December 27, 2015, a new law had passed in the session of the National People's

Congress Standing Committee, effective from January 1, 2016. However, in 2018,

about two years after the new policy reform, China was already facing new

ramifications. Since the revision of the one-child policy, 90 million women

have become eligible to have a second child. And thus according to The

Economist, the new two-child policy may have negative implications on gender

roles, with new

expectations from females to bear more children and to abandon their careers.

If you thought that

this phenomenon was restricted to advanced economies in the West, though, you

would be mistaken. Russia, the whole of eastern Europe, Singapore, Hong Kong,

Taiwan, and South Korea are also aging rapidly but China, by some important measures

is the fastest aging country on the planet.

Rudong

County is representative

of Chinese places with the highest proportion of elderly. At some point, it

will suddenly be recognized as critical. The good news is that China still has

some time to address the consequences of aging. Demographics are not destiny,

and there are coping mechanisms available to deal with the consequences.

Click on image to see the growth of the

population there:

The above image shows the growth of

Dalian in China.

The bad news, though,

is that the time that is available is passing by rapidly. Consider that in

advanced countries, the cohort of those aged over sixty roughly doubled to

about 24 percent of the population between 1950 and 2015. At that point, per

capita income was about $41,000. In China, this process is going to take just

twenty years, less than a third of the time it took in richer countries. Those

aged over sixty-five as a share of the population will double to 25 percent by

2030. As I write, that is only a little over eleven years away. If recent

trends persist, income per head in 2025 would still be only a third of the

level in advanced economies in 2015. Thereafter, China will age faster still.

This is what is meant by ‘getting old before you get rich’. It is a huge

challenge.

The essence of aging

To most people, aging

is about two things. First, it is a celebration of living longer. Second, it’s

about ‘who’s going to look after grandma, or grandpa?’ In other words, it’s

about the care issues we confront in our families and for ourselves as longer

life expectancy gives rise to a greater susceptibility to non-communicable

diseases and disability. Yet the significance of aging for whole societies and

countries, as opposed to us as individuals, is fundamentally about

macroeconomics. It arises because of the unique combination in human history of

weak or falling fertility and rising life expectancy. In fact, while rising

life expectancy is self-evidently something we do both celebrate and worry

about when it comes to care, it isn’t actually the core issue in aging. Rather,

it is low fertility.

Low fertility means

we don’t produce enough children to become workers to fully replace those

reaching retirement. As a result, the size and the growth rate of the

working-age population (WAP), typically defined as those aged fifteen to

sixty-four, are going to stagnate or decline. Low or falling fertility is

pretty much a global issue. In Denmark, France, Russia, Singapore, South Korea,

and Spain, cash or other incentives have been tried to get women to have more

children. In Mexico, there was once a programme to

hand out free iagra to older men. None of these programmes or gimmicks has worked. In China, the coming

dearth of younger people and glut of older aged workers with low skill levels

are going to sit uncomfortably with ambitious economic plans, present a serious

social welfare challenge, and validate concerns felt elsewhere about the major

economic consequences triggered by aging.

Although economic

growth is influenced by a broad array of cyclical factors at home and abroad,

trend or potential growth in the longer term rises or falls in line with the

change in the WAP. As the age structure of the population rises, consumption

patterns will change. Households save less, principally because older, retired

citizens receive less income and have to live off or draw down their savings.

Lower household savings mean that unless companies or the government save more,

the rate of investment will come down. Lower investment and a stagnant or

falling WAP drag downtrend growth.

This is going to be

especially relevant to China. Because of lower trend growth, aging societies

could be places where lower inflation and interest rates plant stronger roots.

Or there could be acute skill and labor shortages which push wages and inflation

higher. We don’t know for sure because there is no template, but we have to be

vigilant about both outcomes. There is a new school of thought that argues that

inflation might not pick up because labor shortages won’t happen thanks to the

arrival of robots and artificial intelligence that could drive millions of

people out of work, contributing to chronic technological unemployment. As a

result, we will end up in a low-wage economy in which poverty and income

inequality will become widespread.

We have never had

sustained and large technological unemployment before, though it is hard to be

sure about new technologies, which are about the substitution of both brawn and

brain. There will undoubtedly be difficult years ahead but I lean towards a less

dystopian outcome in which modern technologies will create new jobs and demand

for new goods and services, which are no easier for us to identify today than

they were for previous generations confronted with their technological

challenges. Perhaps countries like China, which have benefited enormously from

outsourcing and inflows of foreign investment and technology, will be at risk.

It will become simpler and cheaper for companies to produce goods and services

locally, and China itself is fast heading towards automation and advance with a

labor force that is still geared more to labor-intensive manufacturing and

agriculture.

In any event, as the

WAP stagnates or contracts, tax revenues become less buoyant at a time when the

larger, older population becomes entitled to pensions and demands more

healthcare and residential care. This places enormous strains on personal

finances and on the resources of national health and care systems.

There is a recurring

fertility pattern in economic development. As people become better off, and as

women especially become more literate, better educated, and urbanize, they tend

to have fewer children. This trend is reinforced as, and if, they benefit from

state-provided social insurance and income support systems.

Lower fertility rates

mean that child dependency, measured by the number of children aged 0–14 as a

share of the WAP, declines. It falls all the faster as the WAP itself expands

as a result of previously higher birth rates. For a while then, lower fertility,

and a more rapidly growing WAP, bring a sort of ‘sweet spot’ to the economy.

Incomes, consumption, savings, and investment all grow more strongly, and these

trends continue for some time before old-age dependency, measured by the number

of those aged 15–64 as a share of the WAP, increases. This phase is known as

the ‘demographic dividend’. It is open to all countries to exploit, but not all

do. China, for example, is the poster country for successful exploitation. Yet,

if you cast your mind back to the Arab Spring in 2010, for example, you will

recall political and social troubles in countries with favorable demographics.

The key to successful exploitation is employment. A booming WAP is

unequivocally positive for the economy but only if people are productively

employed, and fairly paid.

Eventually, though,

the older members of the WAP reach the retirement or pensionable age, and

spearhead a substantial withdrawal of aging workers from the labor force. Some

may be able to leave the labor force gradually in a phased retirement, but

others may have to leave on a cliff-edge basis, that is from Friday to Monday.

The old-age dependency ratio rises.

In most advanced

countries, the fertility rate has receded below the ‘magic number’ of 2.07

children, which is the replacement rate at which the population size is stable.

The WAP is growing only slowly or is falling. Old-age dependency is going up.

The demographic dividend is banked. With the passage of years, we will have

progressively fewer working-age people to support each older citizen, and the

adverse economic and financial consequences referred to an earlier start to

manifest themselves.

The shift in the age

structure of the population is going to place substantial strains on public

spending, especially as regards pensions, healthcare and long-term residential

care. We don’t know yet precisely how these costs will be financed and paid for,

but the scale of expenditure looking ahead over the next three to four decades

necessitates a thorough rethink – whether you are in Beijing or Berlin – about

the entitlement rights and obligations of citizens and of the state. At an

individual level too, most people do not have enough savings or pension or

other assets to finance twenty or thirty years in retirement, especially when

expensive residential care is needed. The personal finance implications of

aging, therefore, including the need for recourse to help from the state, also

become highly significant for aging societies. If you think these are

problematic in advanced economies, think how much more challenging they are in

China, in general, and in China’s more economically backward rural areas in particular.

Coping mechanisms

What can we do to

deal with the macroeconomic effects of rapid aging? There are really only three

main ways to address the macroeconomics of aging. Think of them as the 3 Ps:

people, participation, and productivity. First, the simplest way of addressing labor

or skill shortages is to import them – that is, immigration. Generally

speaking, though, there is only a handful of countries with immigration rates

that come close to having a material effect on sustaining the WAP. It includes

the US, Canada and Australia, France and the pre-Brexit-referendum UK. The

political climate for immigration, though, has turned markedly more hostile,

and coupled with a historical opposition to immigration in many countries,

including China, other coping mechanisms have better potential.

Second, we can try and

compensate for the weakness in the WAP by encouraging people who are generally

under-represented at work to go to work, or stay on. Typically, these people

tend to be women and older citizens. In China, where, according to Mao Zedong’s

dictum, ‘women hold up half the sky’, women used to participate much more in

the workforce than they do nowadays. Getting more women into the workforce is a

possibility, but it is more problematic than simply providing better maternity

and childcare benefits, which in China are already quite generous. The

government needs to focus on other barriers to child-bearing such as the high

cost of education, healthcare and housing. It ought to be possible for older

worker participation to rise too, but here China has to get to grips with a

very low retirement age – officially sixty for men and fifty-five for many

women – and make rapid strides towards the kind of service-oriented economy in

which older workers find more conducive opportunities to work longer.

Third, the most

enticing but also the hardest way to compensate for the weakness in the WAP is

to get tomorrow’s workers to be more productive, so that less is more, so to

speak. As we know, though, productivity cannot be turned on as if it were a

switch, and for China, this option is of the utmost importance. As the

working-age population declines, China will have to focus on the expansion of

tertiary education and upgrading of skills. Rebalancing and the eventual

deleveraging of finance and the economy will, in any case, mean looking for new

sources of economic growth, with productivity the elixir in China, as indeed

everywhere else.

China’s baby bust

China’s demographics

are perhaps best known because of the one-child policy, introduced in 1979.

This policy has the dubious reputation of being one of the starkest examples

ever of the state’s interference in the reproductive habits of its citizens. It

was scrapped formally in 2015, after several years in which some restrictions

were eased. Reflecting on the policy, we wonder what must have gone through the

minds of the people who devised and implemented it. It achieved very little and

saddled China with premature aging. In other words, it created a major

distortion to the age structure of society from which the country will never

recover.

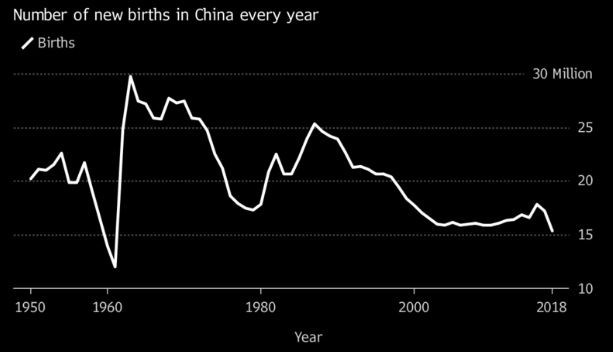

The devastating

demographic effects of the famine from 1960 to 1962 during the Great Leap

Forward crushed China’s fertility. The famine claimed 40–45 million lives and

was responsible for chronic starvation and malnutrition, especially among

mothers and their progeny. China’s fertility rate had been as high as 6.4

children per woman in 1957, but it collapsed to 3.3 children by 1961. In the

years following the retreat from this disaster, fertility recovered as China

had a baby boom from about 1963 to the early 1970s. During this period, the

fertility rate recovered to around 5.8 children.

In 1973, amid

Malthusian concerns about the high birth rate, China introduced new family

planning policies that sought to prescribe later marriage, longer intervals

between births, and smaller family size. By the time the one-child policy was

introduced, the fertility rate had more than halved to reach 2.3 children, not

all that much above the replacement rate. During the period of the one-child

policy, China’s fertility rate carried on falling. In the 1990s, it went down

to 1.45 children, before picking up a bit in the 2000s to about 1.5–1.6

children.

In urban areas, the

one-child policy was implemented as a strict form of social control, for which

compliant residents were compensated by means of pension arrangements at their

place of work. Rural residents were not so fortunate, even though work–life patterns

depended more on children helping out with work and familial care. In the

1980s, the state allowed them the right to bear another child if their

firstborn was female. In 2013, driven by the growing awareness of the weakness

of China’s demographic outlook, all couples were allowed a second child, if

they were both single children.

Whether the one-child

policy had a marked role in lowering the fertility rate, in contrast to other

factors, is a moot point, given

the stance of public policy before the one-child policy was introduced. In

any event, rising living standards still rank as one of the best forms of

contraception. Consider that many places that never had a one-child policy have

the same or lower fertility rates than China. These include Hong Kong,

Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea, Germany, Spain, Greece, Portugal and Italy,

Russia and most of eastern Europe, and Iran.

One

thing that the one-child policy certainly did achieve was a serious gender

imbalance. Compared with a global birth average of about 107–8 boys per 100

girls, China’s gender imbalance was about 116 boys per 100 girls during the

1990s, rising to over 121 boys in 2004. At second or third births, the

imbalance was as high as 130 boys. Since then, the average has fallen back to

about 116–17, though it dipped to 113.5 in 2015.

The announcement at

the third plenum in late 2013 that the one-child policy would be ended was

followed by its final demise in 2015. The impact was immediate, if brief. The

National Health and Family Planning Commission reported a rise in births of

16.6 million in 2016 – a rise of 11.5 percent – pushing the fertility rate up

to 1.7 children. The National Bureau of Statistics, using different data,

reported a rise of 8 percent, or 17.9 million, of whom nearly half were second

children. This was the highest number since 2000, and the biggest annual rise

for thirty years, but in 2017, the number of new births fell back to 17.2

million.

Official hopes that

the abandonment of the one-child policy would spark a new baby boom proved

exaggerated. China’s demographics are not propitious for an enduring rise in

fertility. The number of women aged twenty to twenty-nine is predicted to drop

37 percent by 2025 to just over 71 million, and by nearly half by 2050,

according to United Nations Population Division statistics. The number of

slightly older women, aged thirty to thirty-four years, is expected to hold

steady at around 48–50 million for the next few years, but then drop by a

quarter to about 36 million by 2050. Ultimately, though, the reasons for

China’s low fertility are the same as elsewhere and hinge around rising levels

of income, access to better social security, higher levels of female literacy

and educational attainment, and urbanization.

It is most likely,

then, that China’s fertility rate is going to remain somewhere around current

levels of 1.6–1.7 children, or perhaps weaken still further. According to Yi Fuxian at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Chinese

officials may have been overestimating births for many years, possibly by

about 90 million between 1990 and 2016. Although the official fertility

estimate for 2015, for example, was 1.6 children, he suggests it was more like

1.05 children. If this is even broadly correct, then China’s WAP and total

population over the next twenty to thirty years will be significantly smaller

than expected. This would mean that China is aging even faster than we

currently think, with further and faster increases in old-age dependency

leading to more troublesome economic implications.

China’s demographic dividend is banked in 2012

China’s WAP fell for

the first time, by 3.45 million people, and the rate of decline is going to

accelerate significantly after 2020, with the biggest annual losses (around 7

million a year) occurring between 2025 and 2035. From a current level of just over

1 billion people, the WAP is predicted to decline by 213 million by 2050. This

equates to an average drop of 0.7 percent per year, which feeds directly into

lower trend GDP growth, which may be no higher than 3, possibly 4 percent.

As the WAP declines,

the number of older people will continue to rise relentlessly. Those aged over

sixty, numbering around 209 million in 2015 (just over 15 percent of the

population) will increase to 294 million by 2025 (21 percent of the

population), and 490 million (36.5 percent) by 2050. By then, there will be

nearly three times as many older citizens as children.

The old-age

dependency ratio, which is the number of over-65-year-olds as a proportion of

the WAP, is predicted to rise from 13 percent today, to over 20 percent in 2025

and 47 percent by 2050. Put another way, the 7.7 workers who support each older

citizen today will be just 2.1 workers by 2050. China’s old-age dependency

ratio will still be less than that of Japan and South Korea by then but

significantly higher than the US (37 percent), let alone India (20 percent).

It is an intriguing

question as to why China is aging so rapidly, especially in relation to other

emerging and developing nations. As suggested, though, the combination of the

family planning policies adopted in the 1970s and the one-child policy brought

the demographic dividend to China much earlier. They lowered child dependency

sooner, and have now left the country with premature aging by comparison. While

India’s demographic dividend phase is only just starting – a third of the

population is aged under fifteen – China’s began in the early 1970s and

achieved its maximum effect in the quarter-century to about 2012.

We can judge

premature aging by comparing China with some of its Asian neighbours

when they had China’s current income per head many years ago. For example,

China’s age structure – or the ratio of over-sixties to those aged 0–14 – is

two to three times as high as it was in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

Moreover, the size of China’s working-age population today is significantly

larger than it was for these countries, meaning they were able to look forward

to further demographic dividend years. China’s potential for future growth,

therefore, is much less by comparison, because the share of younger workers in

the economy is substantially lower, and China’s WAP is now declining.(Harry X.

Wu, Yang Du and Cai Fang, ‘China’s Premature Demographic Transition in Government-Engineered

Growth’, in Asymmetric Demography and the Global Economy, ed. José Maria

Fanelli, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 187–212.)

Another indicator

that China’s demographic dividend has been banked is the pattern of

unemployment, which has probably been rising. There is a problem of measurement

here because, like other emerging countries, China lacks a robust system for

recording employment and, especially, unemployment. Neither figures prominently

in macroeconomic planning and management, which still tend to be overshadowed

by other quantitative, and often political, targets. Until 2018, the Chinese

unemployment rate had been recorded at about 4 percent, with small variations

either side, for the last sixteen years, before which there were no data. The

unemployment data are of course a political construct, but also statistically

flawed, largely because of a significant under-estimation of the labor force

itself. They also exclude urban workers without hukou (the registration system

according to which citizens are classified as rural or urban), who do not

qualify to register with local employment service agencies, and don’t allow for

the generally weak incentives to register because unemployment benefit levels

are very low. There is, nevertheless, some evidence to suggest there was a

marked change in the rate of unemployment after the mid-1990s, before which the

labor market was still tightly regulated. From the 1980s until then, which

coincides with the emergence of the demographic dividend, the unemployment rate

averaged 3.9 percent, according to one study. From the mid-1990s until 2009,

though, reforms to state-owned enterprises, privatization and increased

labor-market flexibility constituted an altogether different backdrop, against

which the unemployment rate almost certainly rose, slowly at first, but reaching about 10.9 percent in

the period from 2002 to 2009 that ended with the financial crisis.

A decade on,

unemployment is lower, but it is also quite likely that it is, to some extent,

hidden. Jobs are being lost in coal, steel and other sectors where overcapacity

is being tackled. It is not unreasonable to think that rural unemployment has

been in double digits for a long time. We know, moreover, that investment is

trending down. According to a 2012 survey, the unemployment rate may

have been around 8 percent. A new survey of job seekers, started in 2018,

estimated unemployment at just over 5 percent.

In future, though,

aging should tend to soak up unemployment, as labor and skill shortages

develop. Yet, this isn’t always as simple as it seems. Fewer young people are

entering the job market, for example, as we would expect given the demographic

profile of the labor force. While new employment opportunities are constantly

being created, particularly in the service sector, many of these new jobs are

poorly paid, insecure

and require employees to work long hours in often unfavorable conditions.

The robotics revolution,

on the other hand, could threaten job creation and the absorption of even lower

numbers of new working age people. In 2011, for example, Foxconn, the Taiwanese

company that supplies Apple, Samsung and Sony, made headlines by announcing

that it anticipated replacing many of its workers by installing 1 million

robots over the following three to five years. Progress hasn’t been as rapid as

that, but the company reported in 2016 that it had already replaced

60,000 jobs with such devices.

This is the tip of

the iceberg. Over the last five years, China has bought more industrial robots

than anyone else, including Germany, Japan, and South Korea, and over a quarter

of the total sold worldwide in 2015. And currently, China

could surpass the US in artificial intelligence tech. The industrial

policy, Made in China 2025, incorporates a bet by China’s policymakers that the

threat to jobs from machine intelligence will be outweighed by other factors.

The next few years

will represent a test, then, as to whether this bet is going to pay off. Aging

may produce labor and skill shortages. New technologies may restrict those

shortages to the highly skilled and educated, with resulting unemployment or

poor labor market conditions for many citizens in the countryside, countryside,

and less skilled workers in towns and cities.

Is China running out of workers?

The end of China’s

demographic dividend, and the gradual exhaustion of surplus labor in the countryside

are changing China’s labor market dynamics slowly, but inexorably. In the

process, China will have to turn its attention to the only thing that matters

in the long run to economic growth and living standards – the growth of

productivity.

For decades, migrant

workers have been moving to towns and cities, adding to the urban workforce and

working in more productive factories and construction sites. But there comes a

point when that flow of workers slows down, and then pretty much stops. It is

known as the Lewis turning point, named after the Nobel-Prize-winning

development economist Arthur Lewis.

In an economy with

abundant labor in low-productivity agriculture, people move from farms to

factories where productivity and wages are higher. The influx of labor is

associated with higher investment and employment, leading to higher profits and

wages. Lewis observed, though, that as the agricultural labor surplus dwindles,

industrial wages rise still faster, dampening down both profits and investment,

and leading to a slowdown in overall economic growth. This then raises a key

demographic question, which is whether China has reached the Lewis turning

point. Put another way, are the faster growth in Chinese wages and the slower

growth in the economy compatible with the idea that China is running out of

workers?

At first glance, the

labor supply in the countryside doesn’t look to have been exhausted. There are

still over 600 million people classified as rural inhabitants, and United

Nations Population Division estimates suggest that as urbanization proceeds,

their numbers will fall to 500 million by 2025 and 335 million by 2050. Look a

little more deeply, though, and it appears that China may be a lot closer to

running out of productive workers than meets the eye. The slow or limited

progress in relaxing urban hukou eligibility in large cities, to which rural

migrants want to go, is one constraint. The shortcomings of land reforms and

other measures that might give farmers and rural migrants greater financial

security when they left the countryside is another. Demographic factors

constitute still further reasons for caution. According to the IMF, the core of

the WAP, men, and women aged twenty to thirty-nine, has already started to

shrink, very

likely depriving China of most of its supply of low-cost workers quite soon,

probably between 2020 and 2025.

Moreover, the labor

market in the countryside is in flux because the main characteristics of the

population are changing. People are getting older – the average age of farmers

is now in the late fifties – and less mobile in an environment where physical work

is arduous. They tend to be more set in their ways, more disinclined to work

because of age or family care responsibilities, and more unsuitable for work

because of age, disability or illness. The restrictions of the hukou system

also tend to impede the flow of labor, especially of women, who often return

home to care for older family members. It is estimated, for example, that about

80 million older citizens, or roughly 60 percent of the total in China, live

away from cities and better healthcare facilities. About

a fifth of them have incomes below the official poverty line – a phenomenon

often related to the cost of meeting healthcare and hospital expenses.

These developments

underscore the necessity and urgency for economic and political reforms to

change the way China’s economic model works and to boost productivity growth

and labor force participation growth. Immigration into China is very small, and

it is impossible to anticipate any meaningful or politically acceptable level

of immigration that would make a difference to China’s shrinking working-age

population. In 2016, China made it known that it was thinking about setting up

its first-ever immigration office to attract foreign talent to boost the

roughly 600,000 foreigners living in China. In a country of 1.4 billion people,

this

makes Japan’s 2.17 million foreigners in a country of 127 million look almost

plentiful. Such is the Chinese wariness of immigration, though, that nothing

has been formally announced as yet.

Labor force

participation data are sparse in China. The World Bank has reported that labor

force participation in China fell from about 75 percent in the 1990s to about

65 percent. (‘China 2030’, World Bank and Development Research Center of the

State Council, 2013.) About a third of the decline was attributed to the rapid

expansion of tertiary education with college enrolments rising sevenfold since

1990. Thus, the largest falls in participation occurred in the 15–24 and 25–34

age groups. In and of itself, this is no bad thing, especially if higher

skilled and educated young people enter work later, but with the opportunity to

contribute much more.

For the rest, the

bulk of the fall in participation was due to the earlier withdrawal of women

from the workforce, especially in urban areas. Women aged 25–34, in particular,

have tended to leave the labor force – a trend that may have been attributable to

various factors, including the consequences of state-owned enterprise reforms

and subsequent restructuring, which were generally more favourable

to male employees, a decline in the amount of publicly funded childcare, gender

wage differentials, and discrimination.

By the time women

reach the age of retirement at fifty-five or fifty for women in blue-collar

jobs, only 20 percent are still in work. This is a much greater rate of

withdrawal than exists in South Korea, Indonesia, the US or the UK, for

example. It is hard to say whether this is strictly because of the low age of

retirement, the ease of earlier withdrawal from the workforce, the gender wage

gap which is quite stark, or simply cultural issues. Men, by contrast, retain

much higher rates of participation by the time they retire at sixty.

The age of

retirement, though, hasn’t changed since the 1950s, in spite of the steady rise

in life expectancy, and change is long overdue. The government plans to raise

it in future, starting in 2022, although it hasn’t said exactly when or by how

much. It seems likely that a step-by-step approach will gradually lift it to

around sixty-five years, though if speculation that it might take thirty years

is correct, the benefits would not be realizable for a long time. In principle,

a higher retirement age would slow down, but not reverse, the decline in the

WAP, but this would still be a helpful contribution in managing the aging

transition.

Age-related spending, pensions, and healthcare

Until now, we have

considered how aging affects the real, as opposed to the financial side of the

economy. However, the almost fourfold rise in the old-age dependency ratio will

subject China to a substantial fiscal burden. The development of coping mechanisms

can help to mitigate the burden, but China will also have to make difficult

decisions affecting taxation and spending to keep public debt on an even keel.

In their seminal work

in the wake of the financial crisis, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff

asserted that economic growth slows sharply, or even falls, once the ratio of

public debt to GDP breaches 90 percent. (Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S.

Rogoff, This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Princeton

University Press, 2009.) While the mechanical implication here has been

disputed, and may, in any case, be uncertain in a state-driven economy,

economists are right to say that the debt to GDP ratio cannot increase

continuously without important economic implications, even if precise

thresholds of risk are hard to define. Age-related spending in the next twenty

to forty years, though, will bring this chicken home to roost. China’s broadly

defined public sector debt, excluding off-budget and contingent liabilities,

and the debt of state-owned enterprises, is roughly 60 percent of GDP. There is

some room, therefore, for government debt to absorb some of the costs of

age-related financing, but not that much.

China spends about 7

to 8 percent of GDP on pensions and healthcare, or roughly 3.5 percent and

about 4 percent, respectively. There is no question that these proportions will

grow significantly if China is to match the kind of pension and healthcare services

offered by advanced countries today, as its own population structure changes

rapidly to become more like theirs. Or China will err on the side of caution,

and end up with inadequately financed healthcare programmes,

poor health outcomes, and rising pensioner poverty.

The richer Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD) nations typically spend around 8 percent of GDP on pensions, ranging

from 2 percent in Mexico to 16 percent in Italy. They also spend roughly 7 to 8

percent of GDP on healthcare, though again there are large variations, with the

US, for example, spending half as much again. On average, then, OECD countries

spend about 16 percent of GDP on pensions and healthcare, and a range of

long-term studies by the IMF, OECD and European Commission suggests that this

proportion will rise by between 3 and 12 percent of GDP by the middle of the

century. An even longer-run study of age-related spending based on current

laws, including residential care costs, and covering more than a hundred

countries going out to the end of the century argues that richer countries will

have to boost spending from 16 to about 25 percent of GDP. US spending would

have to rise to 32 percent of GDP, and spending in the EU and Japan would have

to increase to 24 and 28 percent, respectively. These increases are

predominantly related to healthcare, because pension reforms in recent years

have already contained expected outlays.18 China’s pension and healthcare

expenditure are predicted to rise from 7 to about 20 percent of GDP. These

predictions are, if anything, on the low side, and are highly sensitive to

fertility and mortality assumptions. Consequently, if the expected

stabilization of fertility at around 1.85 children falls short, and/or if life

expectancy rises further, then these estimates will be overshot.

Another way of trying

to get a handle on what these numbers mean is to look at estimates of their net

present value, a technique to discount all known future obligations back to a

sum that can be understood in today’s cash terms. According to the IMF, the net

present value of pension and healthcare spending in China out to 2050 amounts

to 83.7 percent, and 47.1 percent of GDP, respectively, or roughly 132 percent

of today’s GDP. (IMF, ‘Older and Smaller’, Finance and Development, vol. 53,

no. 1, March 2016.) IMF, Fiscal Monitor, October 2016. This estimate also

chimes with another actuarial forecast that suggests the current social

security system has a financing gap of RMB 86 trillion, which equates to about

122 percent of 2017 GDP.

The fiscal

consequences of aging for China, then, look quite forbidding, in spite of the

fact that the state has worked strenuously in the last fifteen years to improve

and broaden the provision of age-related spending. While China is not unique in

this regard, there is a difficult structural barrier in the shape of the

state’s reluctance to provide comprehensive welfare and pension support for all

citizens, especially rural residents, partly due to the long-institutionalized

rural–urban divide, and partly because of the equally traditional role of

families as the main source of welfare and support.

Logically, the case

for expanding the social safety net, and for the central government to

establish the basis and rules for expansion, is compelling. Health and

education are important contributors to productivity and improving the quality

of human capital. Modern social security and healthcare systems have to

address, in any event, the huge transformation in demand for new and better

healthcare delivery systems occurring as a result of the shift in the burden of

disease towards non-communicable diseases.

Stronger social and

health insurance would also go some way in helping to reduce high household

savings. In China’s case, for example, the IMF has estimated estimated that every 1 yuan of incremental public spending

on health translates into an additional 2 yuan of urban household consumption, and

that every 1 percent rise in the share of GDP accounted for by health,

education and pensions translates into a rise of 1.25 percent in the share of

consumption in GDP.

After the so-called

‘iron rice bowl’, under which state enterprises provided cradle-to-grave care,

was dismantled in the 1990s and 2000s, the government introduced a new social

security system built around individual employment contracts. Employees and/or

employers were made responsible mainly for contributions to pensions and

unemployment, medical, disability and maternity insurance. Former president Hu

Jintao, who emphasized aging as a top policy priority, codified a number of

previous laws and regulations in the 2011 Social Insurance Law as China moved

to extend social insurance, especially pension rights, to people previously

excluded, such as farmers, migrant workers and hitherto ineligible urban

residents.

The current multiple,

regional pension schemes that pay benefits to government employees, salaried

workers in the enterprise sector, and non-salaried workers, including migrants,

provide almost universal coverage for older citizens. They are mostly unfunded,

or pay-as-you-go schemes in which employers and employees both contribute, but

some schemes report pension surpluses, that is an excess of assets over

liabilities, and others report deficits. Often these correspond to the

demographic make-up of provinces. The 13th Five-Year Plan aims to bring them

all into a single, unified, national scheme, although the plan faces resistance

from some regional governments which fear they may either have to subsidize

less well-off peers or face restrictions in accessing pension funds to finance

favored projects.

From a demographic

standpoint, the main problems with China’s pension system are the low

pensionable age, high contribution rates for current workers, who are paying

for the current elderly who never contributed, and low benefits. While coverage

for urban workers is now around 80 percent, it is only about 25 percent for

migrant workers.

In other social

insurance schemes, employers and employees contribute variously to housing and

unemployment and medical insurance funds, while employers only contribute to

disability and maternity insurance funds. The Hong-Kong based NGO China Labor

Bulletin maintains, however, that ‘enforcement of the Social Insurance Law,

even its most basic provisions, has been very lax, and the

majority of workers are still denied the social security benefits they are

legally entitled to’. In trying to resolve disputes, the authorities have

tended to use new schemes and compliance orders rather than using the law.

A strong and

equitable healthcare system is an integral part of people’s sense of

well-being, but also an essential input into high rates of labor force

participation and, therefore, economic growth. China has taken vigorous steps

to improve access to healthcare by dramatically increasing insurance coverage.

The coverage rate rose from 200 million people in 2004 to virtually the whole

population by 2014. In rural areas, coverage rose from around 20 percent a

decade ago to almost

universal coverage in 2017. The policies pursued over this period amount to

perhaps the largest expansion in healthcare insurance coverage ever recorded.

Yet, despite spending

a lot more, the IMF’s judgment a few years ago was that the Chinese healthcare

sector as a whole retains high elements of inefficiency, is fragmented and

offers inadequate and unequal protection for the population. Only 18 percent of

migrant workers have health insurance in urban locations where they live and

work. Many are required to return home to claim benefits through the Rural

Cooperative Medical Scheme, though the government did announce at the end of

2016 that patients could claim reimbursement in the location where they were

being treated. There are not that many general practitioners in China compared

with OECD countries. The IMF noted that while the latter typically have general

practitioners accounting for between 10 and 40 percent of licensed physicians, in China, the

proportion is only 3.5 percent. Medical care is expensive for individuals

too. Out-of-pocket expenses for healthcare have fallen in recent years thanks

to government subsidies, but they nevertheless remained around 30 percent of

total health spending in 2015.

China’s healthcare

system is also still misaligned with the burden of disease. The key health-related

issue in aging is the epidemiological shift away from illnesses associated with

maternity, children and communicable diseases to non-communicable diseases.

According to the World Health Organization, more than 100 million of China’s

202 million older citizens in 2013 had at least one non-communicable disease.

It also reported that in 2012, 80 percent of deaths of people aged over sixty

were due to such causes, and that it expected a 40 percent rise in

non-communicable diseases by 2030, in men in particular. It

predicted that three times as many people would be living with at least one

such disease.

Signs of a steep drop

in birth numbers emerged, as China’s major cities disclosed their birth figures

for 2018. Wenzhou, a manufacturing hub and wealthy coastal city, saw its birth

number drop to the lowest level in 10 years. A neighboring city, Ningbo,

estimated births declined

by about 17 percent.

China will soon have

to make a big push into the expansion and improvements of pensions and

healthcare because the historically and culturally important familial care

system is becoming more complicated. The structure of Chinese families is

changing. Whereas once China had traditional family structures comprising a

couple of generations living under one roof, so to speak, now it has ‘beanpole’

families, which are characterized by multiple generations, separation, and

families with few or no siblings and cousins. In urban areas, younger

generations are better educated than their parents, more white-collar, have a

stronger sense of individualism, and are more mobile. This phenomenon has

increased both physical and cultural distance between family members. Rural

families, by contrast, tend to be relatively more traditional but the burden of

care for children, parents and generations of grandparents fall on fewer,

mostly female, shoulders, especially in families with one child. The government

needs to address the geographical and economic constraints that face all

families in a rapidly aging society, especially as parents, and grandparents

become ill or disabled. The better off may be able to buy domestic help or pay

to admit relatives to private care homes, but most people will need more and

better access to an improved social safety net.

Update 4 January 2019: A top Chinese research institution has now projected

that the population could start shrinking as soon as 2027, three years earlier than

expected, if the birth rate held steady at 1.6 children per woman. The

population, at 1.39 billion in 2017, and the world’s largest could fall to

1.172 billion by 2065, it said.

The figures are the

lowest since the turmoil of Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward, during which

China’s aggressive push to develop industrial power resulted in widespread

famine. The total population fell by 10 million in 1960, with a large number

believed to have starved to death.

For

updates click homepage here