Ideologically, there is little difference between the Islamic State and

other radical Islamic jihadist movements. But in terms of geographical

presence, the Islamic State has set itself apart from the rest. While al Qaeda

might have longed to take control of a significant nation-state, it primarily

remained a sparse, if widespread, terrorist organization. It held no

significant territory permanently; it was a movement, not a place. But the

Islamic State, as its name suggests, is different. It sees itself as the kernel

from which a transnational Islamic state should grow, and it has established

itself in Syria and Iraq as a geographical entity. The group controls a roughly

defined region in the two countries, and it has something of a conventional

military, designed to defend and expand the state’s control. Thus far, whatever

advances and reversals it has seen, the Islamic State has retained this

character. While the group certainly funnels a substantial portion of its power

into dispersed guerrilla formations and retains a significant regional

terrorist apparatus, it remains something rather new for the region, an

Islamist movement acting as a regional state.

The Islamic State has created a vortex that has drawn in regional and

global powers, redefining how they behave. The group's presence is both novel

and impossible to ignore because it is a territorial entity. Nations have been

forced to readjust their policies and relations with each other as a result. We

see this inside of Syria and Iraq. Damascus and Baghdad are not the only ones

that need to deal with the Islamic State; other regional powers, Turkey, Iran

and Saudi Arabia chief among them, need to recalculate their positions as well.

A terrorist organization can inflict pain and cause turmoil, but it survives by

remaining dispersed. The Islamic State has a terrorism element, but it is also

a concentrated force that could potentially expand its territory. The group

behaves geopolitically, and as long as it survives it poses a geopolitical

challenge.

Within Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State represents elements of the

Sunni Arab population. It has imposed itself on the Sunni Arab regions of Iraq,

and although resistance to Islamic State power certainly exists among Sunnis,

some resistance to any emergent state is inevitable. The Islamic State has

managed to cope with this resistance so far. But the group also has pressed

against the boundaries of the Kurdish and Shiite regions, and it has sought to

create a geographical link with its forces in Syria, changing Iraq's internal

dynamic considerably. Where the Sunnis were once weak and dispersed, the

Islamic State has now become a substantial force in the region north and west

of Baghdad, posing a possible threat to Kurdish oil production and Iraqi

governance. The group has had an even more complex effect in Syria, as it has

weakened other groups resisting the government of Syrian President Bashar al

Assad, thereby strengthening al Assad's position while increasing its own

power. This dynamic illustrates the geopolitical complexity of the Islamic

State's presence.

History of an Idea

The Islamic State has a library of ancient myths and prophecies it uses

to lure warriors in a march towards the thirteenth century, where they will

defeat the infidels in a great final battle in northern Syria. Whether they die

and are rewarded with paradise or survive to enjoy the coming Utopia under

divine rule, they will be the victors; and this is the appeal of the Islamic

State.

On the 4th of July, Ibrahim ibn Awwad ibn Ibrahim ibn Ali ibn

Muhammad al-Badri, alias Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi took center stage in the Grand

Mosque in Mosul for the first time as Caliph Ibrahim, the Emir of the Faithful

in the Islamic State. He wore the black robes of the Abbasids Caliphate that

reigned from 750 to 1258.

Muslims throughout the world were commanded to move to the caliphate and

pledge their allegiance to Caliph Ibrahim. He had been appointed by the Shura

Council that established the caliphate and had acceded to their wishes to

assume the role of the Successor of Mohammad.

Abu Mohammed Adnani, a spokesman for Islamic State, announced to Muslims

worldwide in a commentary titled “The Promise of God” that other organizations

would have to acknowledge the supremacy of Caliph Ibrahim or face the wrath of

the IS. Caliph Ibrahim declared that the Islamic State would encompass in five

years the lands from India to Southern Europe. That would include Mullah Omar’s

caliphate in Afghanistan, which has links to Al-Qaeda. Neither organization has pledged its

allegiance to Abu Bakr Baghdadi. The head of the International Union of Muslim

Scholars, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood and many other

Islamic scholars are also rejecting the demands of Abu Bakr Baghdadi to

acknowledge his supremacy, but not the Islamic principles being promoted and

not the idea of a caliphate.

Caliph Ibrahim offers believers a journey back eight centuries to the

time of the Abbasids Caliphate when Islam was spreading far afield. It is that

lost glory that he is trying to resurrect and impose upon the world. In keeping

with the principles of that distant time, Christians and Jews are to be given

the opportunity to convert, flee, or to pay a tax and live as second class

citizens. All others are to be put to the sword, their property seized, and

their wives and daughters violated and forced into slavery. Everything is spelled out clearly in the

Quran and in the “Majmu’ al-Fatawa”

that was written by Sheikh Taqi ibn Taymiyyah after the fall of the Abbisids Caliphate. It is this doctrine that Ibrahim ibn

Awwad ibn Ibrahim ibn Ali ibn Muhammad al-Badri studied as a doctoral student

in Islamic studies at the Islamic University in Baghdad. The doctrine is a part

of the curriculum at Saudi-financed, Salafi-oriented madrasas.

This is why the Islamic State does not hesitate to display the mass

killing of prisoners or speak openly of enslaving Yazidi women and others.

Their practices were approved thirteen centuries ago and are supported by other

Salafists. Time has not modified those ancient teachings.

Believers are being offered a Utopian promise and the opportunity to

reap revenge upon all of those infidels and false Muslims who have suppressed

righteous Muslims throughout the world and over the centuries. “Revenge,

revenge, revenge,” is the battle cry; and it has all been heard before.

Sheikh Wahhab Is Still

Speaking

By whatever name we call him, the words of the new self-proclaimed

caliph are taken straight out of the mouth of Shaikh Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab, who walked this road of

revolution and reform through much of the eighteenth century. Because Caliph

Ibrahim draws upon historical sources, he can be replaced with another

candidate by the Shura Council if the need arises, thus representing an

institutionalized succession procedure.

Sheikh Wahhab was a fundamentalist that rejected what he saw as the

corrupting of the Faith. The practices of many Bedouins of praying to saints,

giving a spiritual meaning to particular places, celebrating the birthday of

Muhammad, and constructing monuments were all viewed as idolatry. True

believers accept only God and his word.

The Sheikh invoked the practice of Takfir. The rule states that any

Muslim who fails to uphold the Faith should be put to the sword, his property

seized, and his wives and daughters violated. Under this practice, Shia and

Sufis were not considered to be Muslims and not deserving of life.

The Turks and Egyptians who came on their pilgrimages to Mecca were

considered to be particularly abhorrent. They traveled in luxury, smoked, and

were declared to be Muslim pretenders. The sect substituted for nationalism and

was directed against the foreign corrupt rulers before pan-Arab identity began

to unite the tribes.

Ibn Saud, the leader of a minor tribal group in the Nejd saw in the sect a vehicle that could be used to

forward his ambitions. Banditry could be transformed into jihad; and the

defeated tribes could be given the choice of converting to the sect and to

benefit in the spoils or die. If they died in battle, they would enjoy a direct

move into paradise.

What the Wahhabi Sect added to Islamic practice and what appealed to Ibn

Saud was the requirement of the followers to give absolute loyalty to the

political leader. To question the teaching or to fail submitting to the leader

was cause for execution with the loss of property and the violation of wives

and daughters.

By the end of the eighteenth century, the success of Saud was evident

with much of the Arabian Peninsula under his control. His raid upon the

important Shia center of Karbala in Iran 1801 saw an estimated five

thousand Shia slaughtered and their religious sites destroyed. That was

followed two years later by the capture of Mecca and later Medina.

The Ottomans could no longer ignore the carving up of their colonial

territory by a desert tribe. An army of Egyptian troops was sent to settle the

matter. The Wahhabi capital of Dariyah was seized and destroyed in 1818.

Wahhabism receded into the Arabian Desert.

Yet it did not disappear. It remained the core philosophy of the Saud

tribe and would become the core belief of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, from

where it began to spread throughout the Middle East.

Wahhabism arose at a time when the foreign Ottomans were enjoying the

benefits of being colonial rulers, which left a religious and political vacuum

that Wahhabism eventually filled. Exactly one century after it was defeated, it

arose anew with the fall of the Ottoman Empire and its dismembering by the

British and French.

The tribes went from one colonial rule to another without having any say

in what form their lands would take or what type of government would rule.

After World War II, the European rulers were replaced mainly by autocrats.

Where oil was exploited, the autocrats had riches that gave little benefit to

the masses.

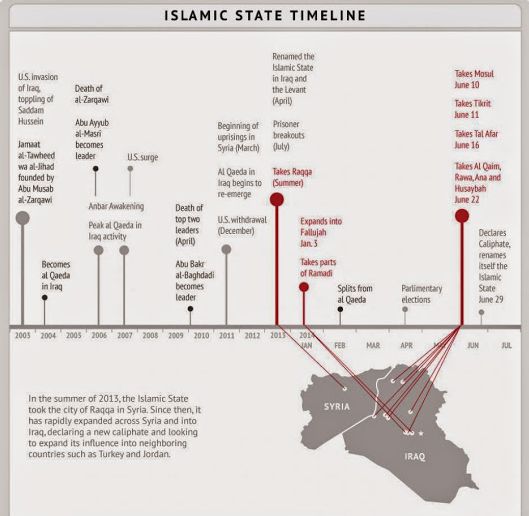

The destruction of the Saddam regime and the dismantling of the state

structure by the United States in 2003 created the next vacuum that would give

a new reform movement the opportunity to grow.

Revenge and Utopia

The strength of the Islamic State is that it gives the millions of

impoverished people who see themselves as oppressed the opportunity to ride

their 21st century tanks back to the promised Utopia, where the religious

pure will reap all of the benefits and the disbelievers will receive their

rewards at the end of a modern version of the sword.

If you believe, then all of the events that are converging in Syria were

prophesized by Mohammad thirteen centuries ago, when he told the future

generations that a great battle between Islam and the infidels would be fought

out in northern Syria at the town of Dabiq near the

Turkish border. That is where the old world will come to an end. It will

precede the arrival of the Mahdi and the end of the world.

Only the purest of the pure from the ranks of Muslims will enjoy the new state

of peace and prosperity.

It has all been foretold, and the falling bombs on Islamic State

positions in northern Syria are giving credibility to the ancient script for

those who believe.

All that is needed to fulfill the prophecy is the arrival of an infidel

army. The taunting of the United States by killing American citizens publically is intended to draw that army onto the

battlefield to unite Muslims against the return of the Crusaders. If the United

States rejects the challenge, it will be declared a coward and will confirm to

followers of the Islamic State their strength. This is sure to give the

movement even more appeal in the eyes of potential jihadists.

Yet it as we point out below, it is unclear whether the Islamic State

can survive. It is under attack by American aircraft, and the United States is

attempting to create a coalition force that will attack and conquer it. It is

also unclear whether the group can expand. The Islamic State appears to have

reached its limits in Kurdistan, and the Iraqi army (which was badly defeated

in the first stage of the Islamic State’s emergence) is showing some signs of

being able to launch counteroffensives.

Countering with a Coalition

The United States withdrew from Iraq hoping that Baghdad, even if unable

to govern its territory with a consistent level of authority, would

nevertheless develop a balance of power in Iraq in which various degrees of

autonomy, formal and informal, would be granted. It was an ambiguous goal,

though not unattainable. But the emergence of the Islamic State upset the

balance in Iraq dramatically, and initial weaknesses in Iraqi and Kurdish

forces facing Islamic State fighters forced the United States to weigh the

possibility of the group dominating large parts of Iraq and Syria. This

situation posed a challenge that the United States could neither decline nor

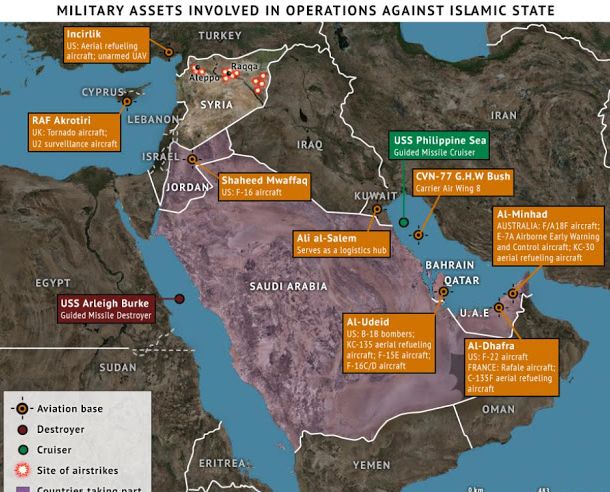

fully engage. Washington's solution was to send aircraft and minimal ground

forces to attack the Islamic State, while seeking to build a regional coalition

that would act.

Today, the key to this coalition is Turkey. Ankara has become a

substantial regional power. It has the largest economy and military in the

region, and it is the most vulnerable to events in Syria and Iraq, which run

along Turkey's southern border. Ankara's strategy under President Recep Tayyip

Erdogan has been to avoid conflicts with its neighbors, which it has been able

to do successfully so far. The United States now wants Turkey to provide

forces, particularly ground troops, to resist the Islamic State. Ankara has an

interest in doing so, since Iraqi oil would help diversify its sources of

energy and because it wants to keep the conflict from spilling into Turkey. The

Turkish government has worked hard to keep the Syrian conflict outside its

borders and to limit its own direct involvement in the civil war. Ankara also

does not want the Islamic State to create pressure on Iraqi Kurds that could

eventually spread to Turkish Kurds.

Turkey is in a difficult situation. If it intervenes against the Islamic

State alongside the United States, its army will be tested in a way that it has

not been tested since the Korean War, and the quality of its performance is

uncertain. The risks are real, and victory is far from guaranteed. Turkey would

be resuming the role it played in the Arab world during the Ottoman Empire,

attempting to shape Arab politics in ways that it finds satisfactory. The

United States did not do this well in Iraq, and there is no guarantee that

Turkey would succeed either. In fact, Ankara could be drawn into a conflict

with the Arab states from which it would not be able to withdraw as neatly as

Washington did.

At the same time, instability to Turkey's south and the emergence of a

new territorial power in Syria and Iraq represent fundamental threats to

Ankara. There are claims that the Turks secretly support the Islamic State, but

I doubt this greatly. The Turks may be favorably inclined toward other Islamist

groups, but the Islamic State is both dangerous and likely to draw pressure

from the United States against any of its supporters. Still, the Turks will not

simply do America's bidding; Ankara has interests in Syria that do not mesh

with those of the United States.

Turkey wants to see the al Assad regime toppled, but the United States

is reluctant to do so for fear of opening the door to a Sunni jihadist regime

(or at the very least, jihadist anarchy) that, with the Islamic State

operational, would be impossible to shape. To some extent, the Turks are

floating the al Assad issue as an excuse not to engage in the conflict. But

Ankara wants al Assad gone and a pro-Turkey Sunni regime in his place. If the

United States refuses to cede to this demand, Turkey has a basis for refusing

to intervene; if the United States agrees, Turkey gets the outcome it wants in

Syria, but at greater risk to Iraq. Thus the Islamic State has become the focal

point of U.S.-Turkish ties, replacing prior issues such as Turkey's

relationship with Israel.

Iran's Changing Regional Role

The emergence of the Islamic State has similarly redefined Iran's

posture in the region. Tehran sees a pro-Iranian, Shiite-dominated regime in

Baghdad as critical to its interests, just as it sees its domination of

southern Iraq as crucial. Iran fought a war with a Sunni-dominated Iraq in the

1980s, with devastating casualties; avoiding another such war is fundamental to

Iranian national security policy. From Tehran's point of view, the Islamic

State has the ability to cripple the government in Baghdad and potentially

unravel Iran’s position in Iraq. Though this is not the most likely outcome, it

is a potential threat that Iran must counter.

Small Iranian formations have already formed in eastern Kurdistan, and

Iranian personnel have piloted Iraqi aircraft in attacks on Islamic State

positions. The mere possibility of the Islamic State dominating even parts of

Iraq is unacceptable to Tehran, which aligns its interests with those of the

United States. Both countries want the Islamic State broken. Both want the

government in Baghdad to function. The Americans have no problem with Iran

guaranteeing security in the south, and the Iranians have no objection to a

pro-American Kurdistan so long as they continue to dominate southern oil flows.

Because of the Islamic State, as well as greater long-term trends, the

United States and Iran have been drawn together by their common interests.

There have been numerous reports of U.S.-Iranian military cooperation against

the Islamic State, while the major issue dividing them (Iran's nuclear program)

has been marginalized. Monday's announcement that no settlement had been

reached in nuclear talks was followed by a calm extension of the deadline for

agreement, and neither side threatened the other or gave any indication that

the failure changed the general accommodation that has been reached. In our

view, as we have always said, achieving a deliverable nuclear weapon is far

more difficult than enriching uranium, and Iran is not an imminent nuclear

power. That appears to have become the American position. Neither Washington

nor Tehran wants to strain relations over the nuclear issue, which has been put

on the back burner for now because of the Islamic State's rise.

Last Sunday also, Shiite and Sunni clerics from about

80 countries gathered in Iran's holy city of Qom to develop a strategy to

combat extremists, including the Islamic State group that has captured large

parts of Iraq and Syria.

New role of the United States?

This new entente naturally alarms Saudi Arabia, the third major power in

the region if only for its wealth and ability to finance political movements.

Riyadh sees Tehran as a rival in the Persian Gulf that could potentially

destabilize Saudi Arabia via its Shiite population. The Saudis also see the

United States as the ultimate guarantor of their national security, even though

they have been acting without Washington's buy-in since the Arab Spring.

Frightened by Iran’s warming relationship with the United States, Riyadh is

also becoming increasingly concerned by America’s growing self-sufficiency in

energy, which has dramatically reduced Saudi Arabia's political importance to

the United States.

There has been speculation that the Islamic State is being funded by

Arabian powers, but it would be irrational for Riyadh to be funding the group.

The stronger the Islamic State is, the firmer the ties between the United

States and Iran become. Washington cannot live with a transnational caliphate

that might become regionally powerful someday. The more of a threat the Islamic

State becomes, the more Iran and the United States need each other, which runs

completely counter to the Saudis' security interests. Riyadh needs the tensions

between the United States and Iran. Regardless of religious or ideological

impulse, Tehran's alliance with Washington forms an overwhelming force that

threatens the Saudi regime's survival. And the Islamic State has no love for

the Saudi royal family. The caliphate can expand in Saudi Arabia's direction,

too, and we've already seen grassroots activity related to the Islamic State

taking place inside the kingdom. Riyadh has been engaged in Iraq, and it must

now try to strengthen Sunni forces other than the Islamic State quickly, so

that the forces pushing Washington and Tehran together subside.

What is noteworthy is the effect that the Islamic State has had on

relationships in the region. It has also

revived the deepest fears of Turkey, Iran and Saudi Arabia. Ankara wants to

avoid being drawn back into the late Ottoman nightmare of controlling Arabs,

while Iran has been forced to realign itself with the United States to resist

the rise of a Sunni Iraq and Saudi Arabia, as the Shah once had to do.

Meanwhile, the Islamic State has raised Saudi fears of U.S. abandonment in

favor of Iran, and the United States' dread of re-engaging in Iraq has come to

define all of its actions.

It appears that Turkey, Iran and Saudi Arabia are all waiting for the

United States to solve the Islamic State problem with air power and a few

ground forces. These actions will not destroy the Islamic State, but they will

break the group's territorial coherence and force it to return to guerrilla

tactics and terrorism. Indeed, this is already happening. But the group's very

existence, however temporary, has stunned the region into realizing that prior

assumptions did not take into account current realities. Ankara will not be

able to avoid increasing its involvement in the conflict; Tehran will have to

live with the United States; and Riyadh will have to seriously consider its

vulnerabilities. As for the United States, it can simply go home, even if the region

is in chaos. But the others are already at home, and that is the point that the

Islamic State has made abundantly clear.

For updates

click homepage here