By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

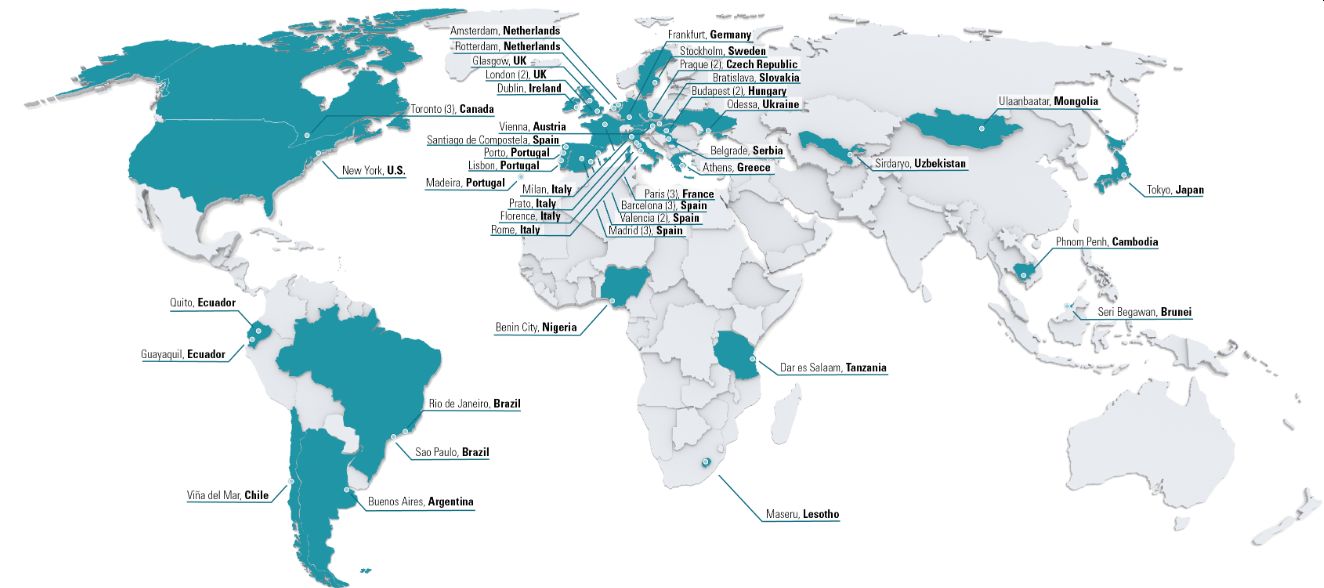

Chinese Overseas Police Service Stations

Commenting on three

serious indictments announced by Attorney General Merrick Garland, we

reported on 24 October how China's spy agency, the Ministery Of State Security (MSS), fooled the western

world into projecting an alleged Chinese

peaceful rise by using middlemen, for example, John L. Thornton chairman

of the board of the Brookings Institution.

The indictments also

charged seven Chinese citizens with participating in a scheme to force a Chinese-born U.S. resident living in New

York to return to China. Which used a “global extralegal effort” on the part of the Chinese

government known as “Operation Fox Hunt,” Garland said, referring to a worldwide

effort launched by Beijing in 2014 to force fugitives, dissidents, and

whistleblowers to return to China.

It has been known for

some time the Government of China is engaged in espionage overseas, directed

through diverse methods via the Ministry of State Security (MSS), the Ministry

of Public Security (MPS), the United Front Work Department (UFWD), People's

Liberation Army (PLA); (vis-à-vis the Intelligence Bureau of the Joint Staff

Department) and numerous front organizations and state-owned enterprises.

One trend in recent

years is the use of criminal law against political dissidents, who are often

charged with minor criminal offenses (such as disturbing public order) and then

locked up for several years as punishment. Another trend is the illegal house

arrest of innocent people who have not been charged with any crime, such as

Chen Guangcheng, a blind human rights activist, and Liu Xia, wife of jailed

Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo. Perhaps the most disturbing trend in the

use of unorthodox methods of repression is the employment of thugs by local

authorities to harass and beat political dissidents.1

The CCP’s repressive

capacity consists of several layers. Within Chinese society, the regime employs

a vast network of informers who monitor the activities of their fellow citizens

and provide intelligence to the government.2 The second layer centers on the

regular police force (which has specialized departments for domestic political

security) and the secret police (part of the Ministry

of State Security).

A third layer, added

in the late 1990s, is commonly known as the Internet police, which patrols

Chinese cyberspace. The fourth layer is the People’s Armed Police, a

paramilitary force trained and equipped to quash riots and restore order on

short notice (authorized to use lethal force). In addition to these networks

and organizations, the CCP has also established special offices at each level

of the state that coordinate activities related to internal security.

This vast apparatus

of repression enables the regime to respond to and quash social protests

instantly and prevent small incidents from mushrooming into destabilizing

events. Over the years, the party-state seems to have followed standard

operating procedures that have proven their effectiveness. Typically, these

procedures mix carrots and sticks. Local government officials, depending on

circumstances, may choose concessions over repression when the latter might

lead to escalations in violence. But on other occasions, local officials would

resort to more brutal means of suppression. As a result, the regime has been

able to cope with a rapid increase in social protest since Tiananmen (there are

around two hundred thousand “mass incidents,” or collective riots and protests,

in the country each year, according to academic estimates).3

The most notable

aspect of political repression in the post-Tiananmen era is the combination of

overt repression (such as arrests and imprisonment) of dissent with unorthodox

methods. In some cases, such methods are non-violent. For instance, dissidents

and human rights activists would be invited to have “tea” with policemen and

receive warnings about their activities. The government would also forcibly

take them away from their homes for “vacations” in remote areas on sensitive

anniversaries or occasions when key Western leaders visit China.

But more prevalent is

the use of coercive and violent means. One trend in recent years is the use of

criminal law against political dissidents, who are often charged with minor

criminal offenses (such as disturbing public order) and then locked up for

several years as punishment. Another trend is the illegal house arrest of

innocent people who have not been charged with any crime, such as Chen

Guangcheng, a blind human rights activist, and Liu Xia, wife of jailed Nobel

Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo. Perhaps the most disturbing trend in the use of

unorthodox methods of repression is the employment of thugs by local

authorities to harass and beat political dissidents.4

The Patriotic Education Campaign

As we have discussed,

the fourth pillar of the CCP’s post-1989 survival strategy is the manipulation

of nationalism as a source of legitimacy. In the 1980s, Chinese nationalism had

a moderate orientation, mainly due to the relatively liberal political

environment and the policies of reform-minded top leadership.5 This changed following

the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown. The ruling elites identified nationalism as a

critical source of legitimacy and subsequently implemented a systematic and

highly effective program of reconstructing Chinese nationalism. The so-called

patriotic education campaign was the centerpiece of the post-1989

state-sponsored revival of Chinese nationalism. This comprehensive program

revamped history textbooks, reconstructed national narratives, and renovated

historical sites and symbols throughout China. The sole purpose of this program

was to rekindle the Chinese population’s sense of national humiliation and,

consequently, their antipathy toward the West.6

During the 1980s, mainly due to the relatively liberal

political environment and the policies of top reform-minded leadership, Chinese

nationalism had a moderate orientation. This changed following the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown when

history and memory were developed to become a new power.

The so-called

patriotic education campaign was the centerpiece of this post-1989

state-sponsored revival of Chinese nationalism. This comprehensive

program revamped history textbooks, reconstructed national narratives, and

renovated historical sites and symbols throughout China. The sole purpose of

this program was to rekindle the Chinese population’s sense of national

humiliation and, consequently, their antipathy toward the West. The “patriotic

education campaign” successfully reawakened the most parochial and xenophobic

strains of Chinese nationalism. Through official propaganda and a distorted

historical narrative, the CCP convinced large segments of the Chinese

population that the West would not want to see a powerful and prosperous China.

Periodically, the official propaganda apparatus would go into overdrive

whenever there were international incidents in which China was apparently

disrespected or poorly treated. The first example we have previously analyzed

was the 1995-1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis. Other examples are the accidental bombing

of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade by NATO during the Kosovo war in 1999 and

the midair crash between a Chinese fighter jet and an American navy

reconnaissance plane over the South China Sea in 2001. Of course, American

responsibility in some of these made it easier for the Chinese regime to

convince their population that the United States harbored hostile intent toward

China. For instance, Washington attributed intelligence failure to bombing the

Chinese embassy in Belgrade. This might be true, but it sounded unconvincing to

the average Chinese, who firmly believed that the United States, the world’s

most advanced country, was incapable of making such dumb mistakes.

Deng Xiaoping’s

strategy, meanwhile, was the redefinition of the “one-hundred-year history of humiliation”

as a new source of legitimacy of the CCP’s rule and the unity of the

Chinese people and society.

If Chinese economic growth slows down significantly and, as a result,

the CCP’s performance-based legitimacy declines, the regime will likely have to

rely on this extensive, sophisticated, and highly effective apparatus of

repression for survival.

Chinese operations

worldwide eschew official police and judicial cooperation, violate the

international rule of law, and may violate the territorial integrity of third

countries involved in setting up a parallel policing mechanism using illegal

methods.

The U.K., Spain,

Portugal, Netherlands, and Belgrade are among the countries investigating

claims the stations are used to force the Chinese to go home. Ireland on

Thursday, 27 October, ordered Beijing to shut down its "overseas Chinese

police service center" in Dublin, as the Dutch government said it would

investigate media reports about Chinese police offices in the Netherlands,

which are believed to enable Chinese police to operate illegally overseas.

Canada’s federal police

force is investigating reports that clandestine Chinese “police stations” are operating

in Toronto amid reports of a global network used to target overseas

dissidents.

1. See Xu Youyu and Hua Ze, eds., In the Shadow of the Rising Dragon:

Stories of Repression in the New China (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013).

2. The existence of

networks of informers is kept secret and is poorly studied. Occasionally one

comes across a reference to it. For instance, this network was mobilized during

the Beijing Olympics to ensure security. Peter Coates, “Beijing Spying

Apparatus Gears Up for Olympics,” Newsweekly, May 10,

2008, https://ncc.org.au/uncategorized/3535-china-beijing-spying-apparatus-gears-up-for-olympics/

.

3. Yanqi Tong and Shaohua Lei, “Large-Scale Mass Incidents and Government

Response in China,” International Journal of China Studies 1, no. 2 (2010):

487–508. (October 2010); Christian Gobel and Lynette

Ong, “Social Unrest in China,” European China Research and Advice Network

Report (2012).

4. See Xu Youyu and Hua Ze, eds., In the Shadow of the Rising Dragon:

Stories of Repression in the New China (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013).

5. Guoguang Wu provides an excellent analysis of the contrast

between nationalism before 1990 and afterward in Wu, “From Post-Imperial to

Late-Communist Nationalism,” Third World Quarterly 3 (2008): 467–82.

6. Zheng Wang, Never

Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign

Relations (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014).

For updates click hompage here