The speedy growth of

India’s information technology (IT) sector during the 1990s put India in the

limelight, with analysts worldwide claiming that India was on its way to

becoming a global superpower with its giant, cheap labor pool, trained English

speakers and considerable expertise in the IT industry. The then-ruling Bharatiya Janata

Party coined the term “Shining India” to mark India’s ascent into

the developed world, leading popular Western journalists to clamor over the

idea that a McDonald’s made Bangalore the next San Francisco.

India simply suffers

from one too many structural deficiencies to even come within sight of

superpower status. Though the West quite naturally views liberal democracies

positively, the Indian democracy is a different story. Split across geographic,

economic, linguistic, cultural, religious, political and ideological lines,

India is incapable of coordinating and implementing high-level policy among the

national, regional and local governments. The country is still in a deep

struggle over how to accelerate growth in the IT sector, while India’s

agricultural sector, which employs more than 60 percent of the country’s labor

force and grows annually at a staggeringly low rate, continues to lag behind.

Add to that rampant corruption and a bloated bureaucracy, and any chance of

lifting India’s infrastructure from its sorry state of affairs in even premier

cities like Bangalore is near impossible.

And it gets worse.

India is in a dire energy situation. Already, companies in India have grown accustomed to

hours-long blackouts, especially in the hot summer months. But with crude

prices soaring, India’s energy dilemma is coming to a head with blackouts

becoming longer and more frequent and state refiners buckling under pressure,

and the government is doing anything it can to avoid riots over fuel shortages.

With growth slipping, inflation soaring and food prices increasing, India is in

a difficult spot in managing the effects of the global commodity crisis.

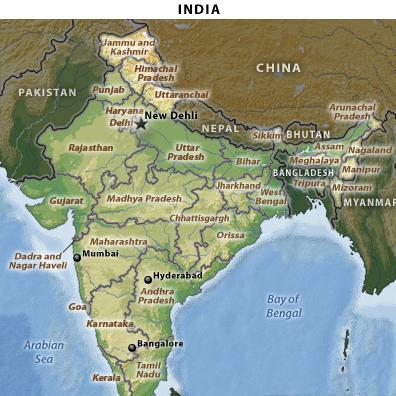

And then there

is the security angle. India suffers from a wide array of militant threats,

including an energized Maoist-influenced Naxalite movement running from the

northeastern Indian state of Bihar to the southern state of Andhra Pradesh, a

mix of separatist insurgencies in the bottlenecked northeast and an Islamist

militant movement concentrated in Kashmir with cells sprinkled throughout

India’s major urban areas.

Though the Indian

Intelligence Bureau (IB) is among the top in the world when it comes to its

ability to conduct surveillance, the IB still has its shortcomings when it

comes to infiltrating militant groups and coordinating counterterrorism

operations across state lines. The Naxalite movement, while concentrated in the

more rural (and mineral-rich) areas of India, has proven quite adept at

circumventing India’s security apparatus and is thriving on the government’s

inability to manage land disputes between displaced villagers and corporations

struggling to get their investments off the ground in India.

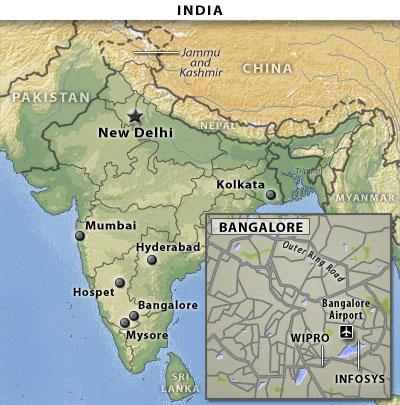

The current

Bangalore/Ahmedabad blasts and came less than a year after a series of

explosions hit the city of Hyderabad, Bangalore’s twin IT hub. These two attacks, though

both amateurish in nature, reveal a gradual shift in Kashmiri Islamist militant

cells’ operations toward a more strategic targeting of India’s prized IT sector

— something that we have long been expecting. Though IT installations were not

specifically targeted in the Bangalore and Hyderabad attacks, the fact that

these two cities are on the militants’ radar is enough cause for concern for

multinational corporations (MNCs) operating in India.

Around 40 percent of

the country’s IT sector is concentrated in Bangalore, where around 36 percent

of the country’s computer software is exported. A large number of MNCs are

located in this IT hotbed, including Microsoft, Dell, Applied Materials,

National Instruments, GM, Google, Goldman Sachs, Honeywell, Intel and IBM. Most

foreign IT companies operate on campuses in the city outskirts of Bangalore and

Hyderabad. Their locations allow controlled access to the campus buildings,

greater standoff distance and concentric rings of security around the main

buildings to better immunize these companies from an outside attack. That said,

there are growing indications that Islamist militant groups are focusing their

recruiting efforts on employees working within the IT industry, thus raising

the threat of an attack being facilitated from the inside.

A number of foreign

investors have already begun second-guessing their cost-benefit analysis of

setting up shop in India after getting a rude awakening of what it means to do

business in a country where communal riots, infrastructural breakdowns, abrupt changes

in regulation and militant attacks are a constant worry. The country’s biggest

strength is that it has a large pool of English speakers willing to work for

low wages. The problems with this model are that wages in the IT sector are

rising; many IT companies have grown weary of dealing with customer complaints

who find Indian customer service intolerable; and pouring additional money into

securing these IT campuses is undermining the cost-effectiveness of doing

business in India. Furthermore, setting up call centers requires a relatively

low amount of foreign direct investment, making it a lot less painful to pack

up and relocate to more favorable investment climates, like Israel, Ireland or

Indiana.

India is unlikely to

experience a mass exodus of investment from the companies that have already

absorbed the cost of doing business in the country. But developments such as

the Bangalore and Ahmedabad blasts are bound to have a negative effect on

future investment into the country, taking more of the shine off the Indian

success story.

A US state department

report has put India at the top of the list of countries worst afflicted by

terrorism.

It says that India

had more than 2,300 terrorism-related deaths in 2007 - about 10% of a worldwide

figure of 22,000 terrorism-related deaths that year.

That is an

astonishing number considering many of those 22,000 worldwide deaths occurred

in Iraq and Afghanistan where wars are being fought.

It's not just the

Islamic jihadis but also separatists like the United Liberation Front of Assam

(Ulfa) and Maoist rebels in India who use serial

bombings on a regular basis.

The US report also

questioned India's "outdated and out burdened law enforcement and legal

systems".

"Until we modernise our intelligence gathering and hold it publicly

accountable, we cannot win the fight against terrorism," says Amiyo

Samanta, a former Intelligence Bureau joint director and retired chief of

police intelligence in West Bengal state.

For updates click homepage here