Earlier I explained that Greece

has a history of defaults/ refinancing, and what the current problem with European Banks is.

Former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan went even as far as to claim that The European Union is doomed to fail

because the divide between the northern and southern countries is just too

great, former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan told CNBC. Meanwhile eurozone leaders

gathered in a summit Wednesday, the fourth in less than a week, out of which

they had hoped to issue a firm line to address the financial crisis that has

now reached its 21st month. Meanwhile, and more importantly, the German

parliament voted overwhelmingly to bar any further expansion of European

bailout structures that might require a greater contribution by Germany.

There were three specific topics on the summit’s agenda. First, a major

bank repair effort whose approval, it is hoped, could turn Europe’s damaged

financial institutions into a source of strength, rather than a weakness.

Second, a write-down of Greek debt, by at least half, that would give Greece’s

economy a chance to recover, rather than drowning in interest payments.

Finally, the summit was intended to seek an expansion of the eurozone bailout

fund that would give the latter the ammunition to assist, if not directly

underwrite, the broader European recovery effort.

Of the three, only

the first goal solidified, and even then only in

part. While reports late in the day suggest that a voluntary write-down of 50

percent of the value of Greek bonds has been agreed to by bondholders, the

exact details of the plan are not clear. Meanwhile, the Europeans agreed to

increase banks’ capital adequacy ratios, the amount of cash that banks must

hold in reserve, up to 9 percent by June of 2012, something that EU leaders

estimated will cost about 100 billion euros. Considering that by the EU’s own

numbers that reaching that degree of a security blanket

would cost, conservatively, 200 billion euros without even pretending to

address the banking sector’s other problems, the agreement fell well short of

offering a comprehensive solution to the financial problems facing Europe. On

the questions about Greek debt and about bailouts for struggling sovereign

states, the Europeans asserted that they had “reached agreement,” but put off

any specific decisions until the next major summit.

Europe’s financial crisis thus is getting worse by the week. What

started nearly two years ago with Greece’s sovereign debt crisis has since

spread to a half dozen countries, even affecting European heavyweight France,

as well as most of the Continent’s major banks. What has not spread is the

willingness of any particular European state to apply

the necessary volume of resources to address the crisis. In fact, as the vote

in the German parliament shows, even in the face of financial collapse there is

little desire to take the steps necessary to save the structures of modern

Europe.

Such reluctance is understandable; the price to stave off Europe’s

crisis is remarkably high. It is estimates that an

effective attempt to tackle the European crisis would require bailout resources

of about 2 trillion euros. Simply arriving at the

current level of to around 1

trillion euros required a strenuous effort.

The European Central Bank (ECB) does not have full authority over

monetary policy and banks in a manner similar to the

U.S. Federal Reserve, the Bank of England or the Central Bank of Paraguay. When

negotiating the Treaty on Monetary Union, European states reserved control over

their own banks, ceding the least amount of authority possible to the ECB. The

system was only sustainable, politically, economically and financially, as long as everyone was profiting. With the arrival of

multiple debt crises and banking crises and considering a languishing global

export market, the kind of economy that allowed this system to work is gone and

unlikely soon to return.

Considering Europe’s political and economic disunity, the EU’s host of

financial and institutional shortcomings, the sheer size of the problem and the

ever-increasing pressure on governments and banks alike, perhaps the most

notable outcome after a week of largely failed summits was that the eurozone

remained intact. However, on the floor of the German Bundestag on Wednesday, it

was made abundantly clear that the one country that might have the financial

resources to resolve the crisis will not be sharing them. Neither the common

currency nor the common market can exist in a Europe in which the union’s

members are unwilling to share burdens and follow collective rules. Germany at

present is focused on the rules, while the countries in need are focused on the

burdens. Both approaches are correct in their own way, yet both are wrong.

Despite failing to articulate the specifics of any credible financial

resolution to Europe’s debt crisis, this was about as good of a political

response as Europe could hope for given the circumstances. By alluding to, but

not mandating, a restructuring, no crushing pressure has been put on the banks,

yet. By not announcing the details of how the European Financial Stability

Facility will be expanded, European leaders have denied critics for now the

opportunity to proclaim failure. That Germany, the one country whose

participation is required in any solution for Europe, is pursuing its own

interests in such a brash manner does not bode well for Europe’s future.

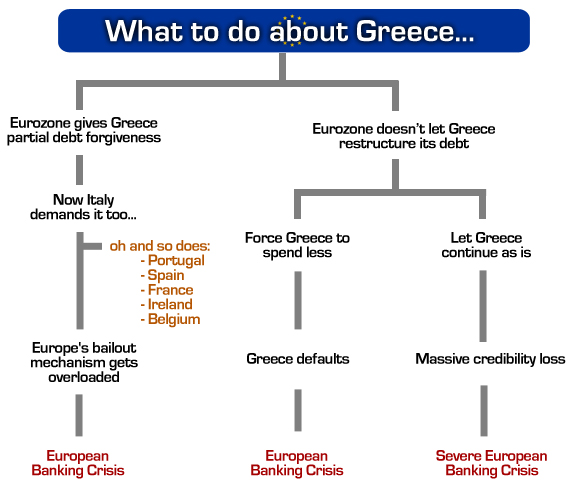

Conclusion: Whichever actions Germany

takes, three things seem all but inevitable: an Italian bailout, a European

banking crisis, and a Greek default. Any one outcome will likely trigger the

other two.

Those betting on a euro breakup however,

believe that the inflation-phobic Germans will never permit large-scale bond

purchases by the European Central Bank, the policy known in the United States

as quantitative easing. But this needs to happen to bail out not only the

Mediterranean governments but also insolvent banks, including German banks,

throughout the euro zone.

And I believe this ultimatly will happen. This

would mean that the European monetary union survives, albeit with a gloomy

future of higher unemployment for southern Europe and higher taxes for the

North.

But the fate of the European Union itself will be very different. The

creation of the single currency, obeying the law of unintended consequences,

set in motion a powerful process of European disintegration. The fact that not

all 27 E.U. members joined the monetary union was its first manifestation.

Today we have a two-tier system, with 17 member-states sharing the euro, but 10

other states, notably Britain, retaining their own currencies.

The result is that key decisions today, particularly those about the

scale of transfers from core nations to the periphery, are being made by the

17, not the 27. But the 10 non-euro members may still find themselves on the

hook to help fund whatever combination of bailout, haircut and bank

recapitalization the 17 decide on. They may also face more stringent financial

regulation or a financial transaction tax, ideas that are much more popular in

Berlin than in London.

This is an unsustainable imbalance. If the euro countries are intent on

going down the road to federalism, and they don’t have a better alternative,

the non-euro countries will face a stark choice: giving up monetary sovereignty

or accepting the role of second-class citizens within the E.U.

Under these circumstances, the logic of continued British membership in

the E.U. looks less and less persuasive. British public opinion has long been

deeply Euro-skeptic. If it came to a referendum, as many Conservatives would

like, Britons might well vote to leave the E.U. And under Article 50 of the

Treaty of European Union, withdrawal would simply need

to be approved by a qualified majority of E.U. members.

For updates click homepage

here