Update 13 January: This and next week will see

a flurry of reviews of “Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood & The Prison of

Belief, by Pulitzer prize winner Lawrence Wright. In his book he details among

others Tom Cruise’s demigod status within the church, as well as the group’s

ultimate purpose, protect humanity from aliens living in our bodies, who are

bent on destroying us and ultimately the planet. David Miscavige the current

leader of Scientology told Cruise, that they were among a select group of

chosen ones, “big

beings” who were destined to meet up with LRH on a planet called “Target Two.”

An excerpt of the book published in The Hollywood Reporter this week,

alleges that Miscavige attempted to cultivate Cruise to become a spiritual

leader. In turn, Cruise ploughed millions of dollars into the church and

attempted to lobby foreign leaders - including former British Prime Minister

Tony Blair - to promote Scientology.

In Going Clear, Wright tracks the tumultuous history of Scientology from

Hubbard’s youth to the Church’s present-day crises, largely brought about by

the mercurial and authoritarian leadership of Hubbard’s successor, Tom Cruise

confidante David Miscavige, who allegedly has a penchant for physically abusing

his underlings and making them salute his dog.

In his book Wright describes Ron Hubbard as possessed with colossal

ambitions from a young age, Hubbard told his first wife, "I have high

hopes of smashing my name into history so violently that it will take a

legendary form," according to Wright.

Hubbard's was coupled with a thirst for adventure and an imagination so

vivid he lived his life as if it were a work of fiction. This is another way of

saying he may have been a pathological liar, as he appears in Wright's

rendering. Born in 1911, Hubbard grew up in Montana yet had an odd seafaring

life. His father was in the Navy, posted in Asia, and periodically Hubbard

shipped out to visit him. In journals Hubbard mythologized his trips into grand

adventures. He had nerve enough for real danger too. Dropping out of college,

he became a stunt pilot. Then, he chartered a schooner, advertised himself as

an experienced sea captain and led more than 50 paying customers on a

"buccaneers" adventure to the Caribbean to explore pirate haunts.

After a series of calamities, Hubbard jumped ship in Puerto Rico.

He discovered a form of adventure for which he was ideally suited:

writing for pulp magazines. Words flowed so quickly, Hubbard typed onto a roll

of butcher paper. He told editors that his stories about cowboys and explorers

were autobiographical. He also claimed to be a nuclear physicist, but his

inability, or unwillingness, to distinguish fact from fantasy was no problem

then. Entering the Navy in World War II, it was. He talked his way into command

of a warship, then during training, led his crew on an epic mission against

Japanese subs that an inquest later determined had never existed. He was

relieved of his command after another incident in which he ordered his men to

bombard Mexico.

After the war, Hubbard drifted to California where he wedded 21-year-old

Sara Northrup while still married to his first wife. He beat her often. Once

while she was sleeping he hit her across the face with his pistol because she

was smiling in her sleep-and therefore must have been thinking about someone

else. When Sara wanted to leave him, Hubbard and a man who might have carried a

gun abducted their baby daughter, Alexis. Then they kidnapped Sara. He told her

that if she tried to leave him, he’d kill Alexis, then later claimed he had

killed the baby already- “cut her into little pieces and dropped the pieces in

a river,” Sara said. In 1951, she filed for divorce, claiming Hubbard to be

“hopelessly insane.” Polly wrote a letter of support, saying, “Ron is not

normal.” Hubbard took the baby to Cuba and kept her in a crib with wire over

the top of it. Later, Sara was able to trick Hubbard to get her child back, and

she walked out of his life on “the happiest day of my life.”

Meanwhile his book "Dianetics" had become a bestseller in 1950

and touched off a movement. Over the next four years Hubbard organized it into

a religion. Scientology, as he rebranded it, offered a lively creation myth

centering on alien invasions and ancient atomic wars.

For many years, Hubbard led his church from a converted freighter with

hundreds of followers aboard on whom he practiced all manner of strange

punishments. Some were locked in hot boxes, fed gruel, dressed in rags. Others

were "overboarded," tied up and tossed in

the sea (then fished out before drowning). Wright describes one instance in

which Hubbard ordered followers "to race each other around the rough,

splintery decks while pushing peanuts with their noses."

Still, there was fun: Hubbard kept his followers active on the Italian

coast hunting treasure that he said he'd buried in a past life.

One of the major strengths of the book is that Wright interviewed dozens

of former members, some of them very high-ranking, who provide titillating

details on a range of subjects; some suggest to him, for instance, that the

Church is essentially holding John Travolta hostage to its whims by

blackmailing him with evidence of homosexuality. There is the Scientology

executive who was physically assaulted by Miscavige’s minions and made to clean

a bathroom floor with his tongue. Wright’s investigations into “The

Hole,” a hidden Scientology gulag in southern California where errant

Church members are sent to perform menial tasks and take part in “org[ies] of self-abasement,” led him to break the story of an

FBI investigation, since aborted, into human trafficking.

28 Dec., 2012: Following a 2003 article about the occult background of

Scientology, in a Jan 2008 commentary I first mentioned the secret vault

and the Underground Church of Spiritual Technology one of Scientology’s most

secretive entities, the Church of Spiritual

Technology with on top circles said to be signposts for reincarnated

Scientologists who come from outer space.

Recently

then confirmation for the above came in the form of lengthy article

containing pictures and location maps and all. In it, Dylan Gill, who helped

build vaults in California and New Mexico -- which each include houses built

specifically for raising the reincarnation of Hubbard -- finally tells his

story.

It also describes that the Church of Spiritual Technology (CST) has a

separate headquarter, a complex in the mountains above Los Angeles, which has a

vault and an LRH House, but no logo visible from the air (the terrain is too

mountainous). It goes by the name “Rimforest” or

“Twin Peaks,” depending on which Scientologist you’re talking to. Here’s a

satellite view…

The place also has other buildings, and it’s where the archiving was

going on that Gill told about. Since 2007, it’s also been the rumored home of

Shelly Miscavige, the wife of the church leader, who suddenly vanished from

view after a career as one of the church’s most prominent executives.

Another likely place for Hubbard to return claimed by Scientology

insiders is another CST location that has the logo visible from the air, but

has no vault, the Creston Ranch where Hubbard died in 1986. Here’s what it

looks like from above…

Plus in latest news, Scientologists may now also be facing their most

daunting court case yet, and all it took was for someone to stop calling them a

cult. After a years long legal battle, federal

prosecutors in Belgium now believe their investigation is complete enough

to charge the Church of Scientology and its leaders as a criminal organization.

Documents

that were seized allegedly provided evidence of extortion of members, of pseudo-medical

practices, and the collection of information of a private nature.

The gist of it is that federal prosecutors have issued indictments to

two senior Scientology executives in Belgium, but also the Belgian organization

itself.

In an article titled Could

Belgium Bring Down Scientology? the Atlantic Wire added: The Church of

Scientology houses its European headquarters in Brussels, so a ban in Belgium

could be crippling to the group, and authorities there seem to know it. One of

the more similar recent cases against came in 2009, when the French chapter of

Scientology was convicted of fraud by a Paris court and fined nearly $900,000.

"But the judges did not ban the church entirely, as the prosecution had

demanded, saying that a change in the law prevented such an action for fraud,"

reported

The New York Times's Steven Erlanger. So the French chapter got saved by a

legal wrinkle, but the Belgian prosecutors don't appear to be backing down.

Belgium is trying to stay away from the “is it a church or a cult”

question, and instead stressed that Scientology should be examined for its

practices, not its beliefs.

Scientology Exposed

There was once a man who considered himself an explorer, a military

hero, a mystic, a philosopher, a nuclear physicist, and an expert in human

nature. In fact, he was none of these things. He was an adventurer, a writer of

pulp fiction, and a teller of tall tales. He was a college dropout, a bigamist,

convicted of petty theft and fraud, and named as an unindicted co-conspirator

in a plot to infiltrate and steal information from U.S. government agencies.

Despite his unimpressive physique, he was a larger-than-life, charismatic

figure who persuaded thousands of people to believe in and pay large sums of

money to learn more about a view of the world he constructed from a foundation

of pseudoscience, bad philosophy, science fiction, and space opera. He came to

believe his own claims of developing the power to shape the world to his tastes

and improve one's physical and especially mental states through specific

techniques he invented that precluded all psychiatric drugs, and yet he died

alone with matted hair and rotting teeth, with the anti-anxiety drug Vistaril

in his system.

He left behind a multi-million dollar global empire of organizations

that continue to generate interest, money, and controversy, much as they did

during his lifetime, and it transformed itself in various ways, from its start

as a replacement for psychotherapy, to a new religion or "applied

religious philosophy;' to a set of "technologies" to be marketed and

sold for the purposes of education, business management, drug abuse treatment,

reducing prisoner recidivism, and combating abuses of psychiatry. After a short

period of uncertainty after his death, another man assumed authority by

systematically eliminating potential competitors and controlling the flow of

information within the organizations.(1)

But now the flow of information has become virtually impossible to

control, and as a result, the empire shows signs of crumbling. With the aid of

the Internet, those inside and outside the organizations that make up the

Church of Scientology can easily find and communicate with each other, and

realize that there are others who share their views and concerns. Records of

past abuses in the form of documents and personal testimony are but a few short

clicks away using a search engine. Virtual communities online have sprung up

and flourished, and real-life actions have been recorded and displayed online

for all to see, producing new conditions of mutual knowledge about what has

been going on in past years, and what's going on now 'And not least of all one

should mention the recent high-level departures.(2)

The practices and history of the Church of Scientology have been

discussed in detail in numerous prior books noted above, but Reitman's is

probably the best comprehensive overview in one book that has yet been

produced.(3)

Any history of Scientology must begin with the biography of its founder,

pulp science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard, who had an extensive record of

biographical fabrication and exaggeration.(4) Other embarrassing details of

Hubbard's life, include his expressions of racism and homophobia.(5)Hubbard can

be said to have been a spiritual ‘bricoleur’, here using the French

anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss's term for a creative recycler of cultural

wares who 'appropriates another range of commodities by placing them in a

symbolic ensemble’. Precursors of Hubbard later works include excerpts from an

unpublished Hubbard work titled Excalibur, written in 1938, which suggests that

Hubbard learned the secrets of reality from a near-death experience during an

operation. Although this might have been inspired by the ideas in the book Seven Minutes To

Eternity by William Dudley Pelley.

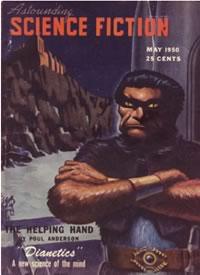

From such and other precursors (some of which I described here and here)

Hubbard's beliefs shifted as the new "science of mental health" of

Dianetics (first introduced to the public in a 1959 issue of Astounding Science

Fiction see above) to the "applied religious philosophy" of

Scientology. Dianetics auditing had led to controversy over past lives by 1951,

and was beginning to clash with medical regulators over claims of diagnosis and

healing, with several Hubbard followers being arrested in the early 1950s.

Although Hubbard created Scientology while living in Phoenix in 1952, where he

formed the Hubbard Association of Scientologists, the first organizations with

‘church’ in their names were formed in New Jersey in 1953 (the Church of

American Science, the Church of Scientology, and the Church of Spiritual

Engineering). The Founding Church of Scientology in Washington, nc. received IRS tax-exempt status in 1956, followed by the

Church of Scientology of California (CSC) in 1957. In 1958, the Washington,

D.C. church had its tax-exempt status revoked on the grounds that it was a business,

a profit-making organization, run by Hubbard for his personal enrichment(6),

but the CSC was apparently overlooked.

While Scientology nominally cloaked itself in some trappings of

religion, this was somewhat perfunctory, and did not prevent an FDA raid on the

Washington, D.C. church in 1963. This was settled in the early 1970s with the

addition of warning labels on E-Meters: The E-meter is not medically or

scientifically useful for the diagnosis, treatment or prevention of any

disease. It is not medically or scientifically capable of improving the health

or bodily functions of anyone:' In a 1962 policy letter titled "Religion;'

Hubbard wrote:

"Scientology 1970 is being planned on a religious basis throughout

the world. This will not upset in any way the usual activities of any

organization. It is entirely a matter for accountants and solicitors" (7).

What the E-meter device does, is it simple measures the ability of the

skin to conduct electricity, which varies with the skin's moisture level. Since

sweat glands are regulated involuntarily by the sympathetic nervous system

rather than by conscious effort. this galvanic skin response cannot be

controlled by someone experiencing a series of emotions. Simply squeezing the

cans to increase the contact area with the skin can also vary the amount of

current measured by the meter.

In 1965, the IRS began an audit of Scientology's records, just as

Hubbard began to move all of his global assets into the CSC to take advantage

of its tax exempt status. This audit led to a revocation of CSC's tax-exempt

status in 1967, which was followed by increased attempts to put on the

trappings of religion, including a February 1969 policy letter calling for

staff to wear clerical collars and for all "orgs" to display the

Scientology cross and the Scientology Creed in public areas. This still,

however, seemed mostly for show. In Nancy Many's book, My Billion Year

Contract, for example, she writes that when she joined Scientology, she was

"told that the religious aspect was for taxes and legal reasons and that

no one had to change their personal faith to become a member" and that

"I had been to only one church service. Only once in twenty years, and I

was in the Sea Org running a large part of Scientology across the entire world

for half of that time:' Many also writes: "Hubbard expressed to me the

thought that going with the whole church angle for Scientology might have been

a mistake in the first place. He felt that the trouble we were currently having

with the IRS would not exist if he had not listened to those around him at the

time and just stayed as a for-profit corporation and just made more money to

pay the taxes." But in Richard Behar's Time magazine cover story from May

6, 1991, he notes that the marketing firm of Trout & Ries was hired by

Scientology to improve its image shortly after Hubbard's death in 1986.

"We advised them to clean up their act, stop with the controversy, and

even to stop being a church. They didn't want to hear that;' Behar quoted Jack

Trout. Trout & Ries was sued by the Church of Scientology in November 1991

as a result of the Time article, on the grounds that the public statement

violated their contract. The lawsuit was settled in August 1994.(8)

John Duignan points out in his book, The Complex, that because

Scientology was not a recognized religion in Scotland, the church operated

through a non-religious organization known as The Hubbard Academy of Personal

Independence, which "was run in exactly the same way as our churches

elsewhere in the UK and across the globe, although it was ostensibly not a

Church of Scientology" (pp. 158-159), and that it used this organization's

putative independence to its advantage, to store sensitive documents from other

countries (p. 159).

Operation Snow White and Tax

Battles

In 1974, Scientology began "Operation Snow White;' the infiltration

of government offices, including the IRS, to steal and "correct"

documents about Scientology. This was a program of Scientology's "Guardian

Office;' a division of the church tasked with responding to attacks on the

church. which engaged in activities ranging from making public embarrassing

information from ex-members' auditing records to trying to frame journalist

Paulette Cooper, author of The Scandal of Scientology, for bomb threats. After

two Scientologists were caught in the U.S. Courts building in Washington, D.C.

and their connection to Scientology was discovered, the FBI raided Scientology

locations in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. on July 8, 1977, which uncovered

tens of thousands of incriminating documents, including the plots against

Paulette Cooper and a plan to portray the Committee for the Scientific

Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP) as a CIA front group.(9)

Eleven Scientologists, seven of them members of the Guardian Office,

were indicted on federal charges, including Hubbard's wife Mary Sue. Although

Hubbard was named as an unindicted coconspirator and was sought by

investigators, he went into hiding. His wife took the fall for him and went to

jail after a negotiated guilty plea to a charge of conspiracy. Hubbard sought

to insulate himself from connections with the church, living under the name

"Jack" on a 160-acre ranch in Creston, California. But he continued

to issue orders through a few trusted Scientologist intermediaries. These were

Pat and Annie Broeker, who lived with him on the ranch, and a young member of

the Sea Org's Commodore's Messenger CMO), David Miscavige.

David Miscavige's Assumption

of Power

In response to the legal troubles surrounding Operation Snow White, a

group within CMO called the "All Clear Unit," which ended up being

led by David Miscavige as its self-appointed leader, was tasked with finding a

way out of the problems. The primary plan 'was to "create a legally

defensible structure that would give Hubbard and the [CMO] full legal control

over Scientology while at the same time 'insulating both Hubbard and the CMO

from any Iegal liability for running the

organizations of Scienrology by lying about the level

of control they really had" (Reitman, p. 129). The Guardian Office was

abolished and replaced by the Office of Special Affairs (OSA) and a complex

corporate structure was put in place. Scientology's operations were put under

the Church of Scientology International (CSI) . while the rights to administer

its intellectual property and determine what constitutes official doctrine was

put under the Religious Technology Center (RTC). Perhaps the oddest corporate

entity, the above mentioned, Church of Spiritual Technology (CST), was founded

by one Scientologist and several non-Scientology lawyers, including the late

Meade Emory, a law professor at the University of Washington and former Deputy

Commissioner of the IRS, who was hired to help create the complex corporate

structure as part of Hubbard's estate planning. This entity is entitled to 90%

of the net income of RTC and has the right to seize key trademarks and

intellectual property from RTC should it judge that organization to be misusing

them. Its primary task appears to be archiving and preserving the works of L

Ron Hubbard in permanent form, which it is doing by inscribing them on

stainless steel plates, putting them in titanium capsules, and placing them in

vaults around the world, such as one near Trementina,

New Mexico, where the CST logo may be seen from the air or on Google Earth.(10)

On January 24, 1986, Hubbard died, and this was revealed to

Scientologists at an event at the Hollywood Palladium two days later, where

David Miscavige announced: "L. Ron Hubbard discarded the body" and

had "moved forward to his next level of research" (Reitman, pp.

142-145). Reitman explains how Miscavige ended up in control of Scientology as

chairman of the board of RTC, after removing Hubbard's wife and dismantling the

Guardian Office, removing the Broekers from power by

assigning Annie Broeker to the Rehabilitation Project Force (RPF), and

appointing allies to key positions, such as Marty Rathbun to Inspector General

of the RTC and fellow CMO member Mike Rinder to head OSA (Reitman, pp.

131-156). Both Rathbun and Rinder have now left the church and are actively

working to promote the practice of Scientology independent of the organization.

Reitman also makes vivid some of the abuses that have occurred with

Miscavige in control, especially at the church's headquarters at

"International Base" or "Int Base" in Gilman Hot Springs,

California, where Miscavige and the senior leaders are based. She describes

cases of physical battery, hard labor without pay in the RPF, coerced abortions

for women in the Sea Org, and the breaking up of families.(11) Scientology has

denied these allegations.

Scientology filed about 200 lawsuits against the IRS, to which 2,300

individual members added their own lawsuits. Seventeen individual IRS officials

were named personally in Scientology lawsuits, accusing them of illegal acts

against the church. Hundreds of Freedom of Information Act requests were filed

with the IRS. Private investigators were hired to attend IRS conferences and

identify IRS agents who seemed to have problems with alcohol or were cheating

on spouses. When Miscavige met with IRS Commissioner Fred Goldberg in 1991,

Miscavige told him all the problems could go away with a settlement, and a

settlement was reached in 1993 (Reitman, pp. 162-166, Urban, pp. 170-177). That

settlement was kept secret by the IRS until it was leaked to the Internet in

December 1997. The settlement granted the church's religious tax exemptions,

settled all accounts for a fraction of claimed owed back taxes, and the IRS

agreed not to audit any church organizations for anything prior to January 1,

1993. Scientology agreed not to sue the IRS for anything prior to the same

date. The settlement also gave Scientologists the right to deduct expenses for

fees paid for auditing or any other religious services (contradicting the U.S.

Supreme Court decision in Hernandez v. Com-missioner, 490 U.S. 680, 1989),

including religious schooling. That last point led to a lawsuit against the IRS

by Michael Sklar, arguing that if Scientologists can deduct expenses for

religious schooling, he should be able to deduct the portion of payments made

to an Orthodox Jewish school for his children that was used for religious

instruction. In 2008, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against Sklar (Sklarv. Commissioner, 282 F.3d 610, 9th Cir. 2002), a

decision that underscores the constitutional problem raised by the different

treatment for Scientology.(12)

Internet War and Lisa

McPherson

In 1991, an online Usenet newsgroup called alt.religion.scientology

was created, and was used mostly by members of the "free zone" -those

who practiced Scientology independently of the church-until 1994. In that year

ex-members started posting Scientology "trade secrets;' which led to raids

on the homes of Dennis Erlich and Arnie Lerma, followed by three major lawsuits

and many more lawsuit threats. The outcome of these lawsuits was that

Scientology's copyrights were upheld, their trade secret claims were overturned,

and the right to quote from and criticize Scientology was preserved.13 The

lawsuits led to real-life protests against churches of Scientology around the

globe, and responses by the church with litigation threats, hiring private

investigators to dig into the personal lives of protesters, and the creation of

online websites to attack online critics. Online information critical of

Scientology proliferated.

On December 5, 1995, a long-time Scientologist named Lisa McPherson died

in the care of Scientology after being kept at the Fort Harrison Hotel in

Clearwater, Florida. Her death received little publicity, no public police

report, and not even an obituary (Reitman, p. 231). But over a year later, on

December 22, 1996, her death was front-page news in the Tampa Tribune

("Scientologist's Death: A Family Hunts for Answers;' by Cheryl Waldrip),

and her death became a renewed focus of protests online and in front of

Scientology orgs, as well as the basis of a criminal prosecution against the

church and a civil lawsuit from McPherson's family. The Lisa McPherson Trust

was set up by critics of Scientology in Clearwater, and new pressure was

directed against the church.

McPherson's case is the primary focus of Part III of Reitman's book, and

she recounts the story more comprehensively than it has been told before. She

shows how McPherson went from a happy, vivacious young lady to a woman who

began exhibiting signs of psychosis. After a minor automobile accident, she got

out of her car and began taking off her clothes, and was taken to a hospital

for observation. But Scientologists came, took her into their care, and held

her captive at the Fort Harrison Hotel without proper medical treatment as her

behavior became more and more erratic. Then after 17 days she stopped moving.

They drove McPherson past several hospitals to one where a Scientologist

physician was on staff, where she was declared dead on arrival. Reitman points

out that David Miscavige personally managed some of McPherson's auditing

sessions and determined that she reached the state of clear (pp. 212-213), and

she documents Scientology's destruction and concealment of evidence in the

case, including by Marty Rathbun (Reitman pp. 224, 237-239). She describes how

the church worked hard to keep McPherson's tragic death quiet by persuading her

family to have her cremated, saying that was Lisa's wish. She describes how the

family was told that she had died of a "fast-acting meningitis"

(Reitman p. 228), with no mention of dehydration while behaving psychotically

and being held prisoner by the Church of Scientology. But what Reitman doesn't

explain is how McPherson's death became publicly known, a year after she died.

What happened in 1996 was that Jeff Jacobsen was preparing a Clearwater,

FL protest against Scientology for its abuses, when a local policeman who was

the liaison for protesters told him that he might find a page on the Clearwater

Police Department web page to be of interest. That web page (called

"homicide.html") requested the public's help in finding information

about three deaths, one of which was Lisa McPherson's. Jeff did not recognize

the name, but recognized her last address as that of Scientology's Fort

Harrison Hotel. He posted a note about Lisa's death to the alt.religion.scientology

newsgroup in November 1996, and contacted Tampa Tribune reporter Cheryl Waldrip

about it. Waldrip thought it was strange that there was no obituary, and

subsequently contacted McPherson's family, which led to the publication of the

front-page story on December 22nd.

In 2000, the medical examiner in Lisa McPherson's case, Joan Wood,

changed the cause of death from "undetermined" to

"accident" and dropped references to her severe dehydration, without

an explanation. As a result, the state attorney dropped the charges on the

grounds that he could not depend on her testimony in the prosecution. In 2004,

the civil case was settled.

Tom Cruise, South Park, and Anonymous Reitman describes how Marty

Rathbun was tasked to bring Tom Cruise back into Scientology after he had

drifted away from the church (pp. 283, 286). Cruise subsequently became a more

zealous public Scientologist than he had ever been, climaxing in the infamous

couch-jumping episode on Oprah (May 23, 2005) and his public criticism of

Brooke Shields for using anti-depressants and subsequent on-air argument about

it with Matt Lauer on NBC's Today show (June 24, 2005).

On November 16, 2005, Comedy Central's animated television series South

Park aired an episode titled "Trapped in the Closet;' which focused on

Scientology and included a summary of the content of Scientology's Operating Thetan Level III cosmology, as well as playing on rumors

about Tom Cruise's sexuality. This content led to the departure of

Scientologist Isaac Hayes from the show (who voiced the character

"Chef"), and the episode was not aired in the UK. It was also dropped

from planned rebroadcasts, though it aired again in 2006 after viewer protests

and can be seen on YouTube. Documents recently released by Scientology's former

RTC Inspector General, Marty Rathbun, reveal that Scientology attempted to dig

up dirt on South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone and their friends as

a result of this episode, allegedly digging through the trash at their office

headquarters in search of receipts or any other documents that might be used

against them.(14)

On January 15, 2008, a video of Tom Cruise that was made for a

Scientology event in 2004 was leaked to the Internet and posted on the website

of the gossip blog Gawker. The Church of Scientology issued legal threats, but

Gawker refused to take down the video, though other sites complied with removal

requests. The video was widely parodied, and Scientology's attempt to remove

the video from the Internet got the attention of "Anonymous;' a chaotic,

loosely organized, originally fictional collective centered around the 4chan

web forums, in particular /b/.4chan allows posts to be made without registering

or logging in, which all show as posted by "Anonymous." This led to

jokes about whether or not there really is an entity called "Anonymous;'

which led to online and real world activity by self-identified members of

"Anonymous."

Conclusion

The final chapter of the Church of Scientology has yet to be written,

but the organization shows signs of experiencing its worst crisis yet as a

result of the exposure of its secrets, the ease of communications between

ex-members, the departure of some of its most senior executives, and the

competition it faces from practitioners of independent Scientology.

Scientologists completed 11,603

courses in 1989, but only 5,895 in 1997 (Reitman, p. 284). The American

Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) estimated the number of self-identified

U.S. Scientologists at 55,000 in 2001, and at only 25,000 in 2008 (Urban, p.

206). Marc Headley, who worked at Scientology's Int base, writes in his

ex-Scientology memoir, Blown for Good (p. 194), that Miscavige wanted enough

Mark VIII Ultra E-Meters to be made for every Scientologist to purchase two,

and 30,000 were produced to match the number of Mark VIIs that had already been

sold. Ex-Scientology marketer Jeff Hawkins estimates the total number of

Scientologists globally at "40,000 or 50,000 max" (Counterfeit

Dreams, Ch.15).

Recent departures include very senior former members such as Marty

Rathbun and Mike Rinder. These former Scientology executives have begun

speaking out publicly and releasing key documents, as well as promoting the

alternative of practicing Scientology independently of the church. While the

church is still a financially formidable force with extensive real estate

holdings, it is now in a very different environment in which its ability to

control information flow among its members and ex-members has been greatly

diminished.

1. Books consulted are: The Story of America's Most Secretive Religion

by Janet Reitman; and The Church of Scientology: A History of a New Religion by

Hugh Urban. John Duignan with Nicola Tallant, The Comp,ex:

An Insider Exposes the Covert World of the Church of Scientology (2008, Merlin

Publishing); Jefferson Hawkins, Counrer'eir Drecms: One Man's Journey Into and Out of the World of

Scientology (2010, Hawkeye Publishing Co.); Marc Headley, Blou'n

for Geod: Behind the Iron Curtain of Scientology (2010, BFG Books); Nancy Many,

My Billion Year Contract: Memoir of a Fonner ScienwIogist

(2009, CNM Publishing); Amy Scobee, Scientology: Abuse at the Top (2010, Scobee

Publishing); Jon Atack, A Piece of Blue Sky: Scientology, Dianetics, and L Ron

Hubbard Exposed (1990, Carol Publishing Group); Paulette Cooper, The Scando.l 0; Scientology (1971, Tower Publications); Russell

Miller, Bare-Faced Messiah: The Story of L Ron Hubbard (1987, Henry Holt) ; Roy

Wallis, The Road to Total Freedom (1976, Columbia University Press).

2. Recent high-level departures who each spent decades on staff inside

the Church include the former #2 person in Scientology (Inspector General of

the Religious Technology Center (RTC)), Mark "Marty" Rathbun; former

head of Scientology's Office of Special Affairs (OSA), Mike Rinder; former

heads of the Scientology Celebrity Centre Nancy Many and Amy Scobee;

Scientology A/V expert and the preclear who was audited by Tom Cruise, Marc

Headley; the marketer who devised the campaigns that put Dianetics back on the

bestseller lists in the 1980s, Jefferson Hawkins: and an Irish Sea brg member who was Commanding Officer of Sci-entology Missions International in the UK, John Duignan.

Rathbun and Rinder are now independent Scientologlsts

on the receiving end of harassment from the Church; Rathbun writes a blog

called "Moving On Up a Little Higher" at httpr/yrnark rathbun.wordpress.comj

where Rinder frequently comments. Many, Scobee, Headley, Hawkins, and Duignan

have each written books about their experiences, of which those by Hawkins and

Duignan (both of whom worked in marketing roles for Scientology) are the best

written and most engaging. Most of these individuals have been criticized

(or" dead agented." in Scientology terminology) for alleged ethical failings

and incompetence, without addressing the question of why they were permitted to

hold positions of significant authority and responsibility in the church if

those charges were true.

3. Many past books on Scientology are available online, see http.y/www.cs.cmu.edu/i-dst/ Libraryjhunt-booklist.html for

a list that includes Atack's A Piece of Blue Sky, Cooper's The Scandal of

Scientology, Miller's Bare Faced Messiah, and Wallis's The Road to Total

Freedom. Atack's book was probably the best comprehensive overview prior to

Reitman's. Miller's book is still the most detailed biography of Hubbard, and

can be found online along with full

transcripts of some of his interviews and copies of relevant source documents,

which can be used to compare his account to Scientology's hagiography. Also see

the FBI Archives on Hubbard (http://www.nots.org/fbiindex.htm). Wikileaks

provides 2,826 pages of Hubbard and Scientology FBI files.

4. An extensive list can be found in Miller's book, Bare-Faced Messiah,

and on numerous sites online, including the Wikipedia entry for Hubbard.

Reitman writes in a footnote on the first page of her first chapter (p. 3) that

Hubbard became the youngest Eagle Scout in the U.S. at the age of 12,

"according to the Church of Scientology." This is actually an

uncorrected error from Scientology; Hubbard did become an Eagle Scout at the

age of 13, which he reported in his diary on March 28, 1924; his actual certificate

was dated April 1, 1924 (http://www.spaink.netj cos/LRH-bio / eaglesco.htrn), and the Boy Scouts kept no record of the

youngest (see Miller, p. 34). One of the few fabrications addressed by Urban is

Hubbard's claim to have been a nuclear physicist; on p. 32 he notes that

Hubbard received an F in the molecular and atomic physics course, which was his

only ground for such a claim. Hubbard, a civil engineering major at George

Washington University, was put on academic probation after getting a D average in

his first year, and dropped out after his second year.

The Church of Scientology's response to Reitman's book claims that her

book is "filled with inaccuracies" but specifically identifies only

one, that she reports the year of his death as 1985 (p. 3), when in fact he

died on January 24, 1986. They don't mention the Eagle Scout error for obvious

reasons

5. As Miller (p. 43) notes, Hubbard's diary of his visit to China in

1928 recorded that "They smell of all the baths they didn't take. The

trouble with China is, there are too many chinks here." (Excerpt from the

diary in his own handwriting is online at http://www.xenu.netjarchive/ booka/apobs/bsz-z.htrn.j

Hubbard re-peated similar racist remarks in the 1950s in recorded lectures

available on YouTube, e.g., a 1952 lecture referring to "chinks"

(http://www.youtube .com/watch?v=YFbkzqflfIQ)

and making a racist joke (http:;/www.youtube .com/watch?v=zZaOeAahrjw). Hubbard identified homosexuality as a

perversion and mental illness in both Dianetics (pp. 122-123) and Science of

Survival (pp. 88-90, a passage re-moved from recent editions), placing it at

rank 1.1 ("covert hostility") on the Scientology "tone

scale." This issue, belatedly discovered by Oscar-winning film director

Paul Haggis after 35 years in Scientology when Scientology's San Diego church

publicly supported California's Proposition 8 against same-sex marriage, led

him to leave in 2009 (reported in detail by Lawrence Wright, "The

Apostate: Paul Haggis vs. the Church of Scientology," The New Yorker,

February 14, 2011, online at http://www.newyorker.com/ reporting/2011/021 14111

0214fa _facCwright).

6. Hugh Urban, The Church of Scientology: A History of a New Religion,

p. 159

7. Urban, p. 160

8. Many, p. 189, p. 74; see also Urban p. 163. In September 1998 the

Mesa, Arizona Org obtained an injunction against Scientology critic Bruce

Petty-crew requiring him to not make any noise that might disrupt nonexistent

Sunday services, then had a private investigator use that injunction as a basis

to contact the Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction to com-plain about Pettycrew and his wife, then a teacher, for their alleged

"anti-religious activities" (http:;/www.soli-tarytrees.netjpickets I

sp880. htm).

The U.S. takes an extreme hands-off approach to religion, putting the

truth or falsity of religious claims outside the scope of the courts (U.S. v.

Ballard, 322 U.S. 78, 1944). In this case, Edna and her son Donald Ballard were

accused of collecting donations on the basis of religious claims they did not

themselves believe. The District Court instructed the jury to find the

defendants guilty of fraud if their religious claims were not sincerely held

beliefs; the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned on the grounds that this

restriction was unnecessary and the jury could rule on the truth or falsity of

the beliefs. The Supreme Court majority opinion, authored by William O.

Douglas, over-turned the Appeals court's position on truth or falsity and

remanded the case to the appeals court, but didn't address the question of

whether sincerity of belief could be examined. Justice Harlan Stone, joined by

Owen Roberts and Felix Frankfurter, dissented, writing that "I cannot say

that freedom of thought and worship includes freedom to procure money by making

knowingly false statements about one's religious experiences." Justice

Robert Jackson took the opposite view in his dissent, arguing that neither

"religious sincerity" nor "religious verity" are legitimate

topics of legal inquiry. The appeals court affirmed the District Court's

original fraud conviction, but it was subsequently overturned on another appeal

to the Supreme Court (329 U.S. 187, 1946), on the grounds that there were no women

on the grand jury or trial jury. In a later case before the 9th Circuit

referencing Ballard. (Cohen v. U.S., 297 F.2d 760. 1962) the court agreed that

questions of truth or falsity are inappropriate. but that this does not mean

"that a court or jury cannot decide that the profession of a belief is

fraudulent." The IRS, however. despite the lack of any basis in the

Constitution or statute, has established a set of 14 criteria for what it means

to be a "church" for the purposes of obtaining tax-exempt status.

9. The Story of America's Most Secretive Religion by Janet Reitman gives

an abbreviated account of "Operation Snow White" and "Operation

Freakout" against Paulette Cooper on pp. 111-112; more detailed accounts

are in Urban (pp. 167-168), in Miller (pp. 336, 341-342, 351-352), and

especially Atack (pp. 226-241). The plot against CSICOP, described in a

six-page "Guardian Programme Order" dated

March 24, 1977 and titled "Programme Humanist

Humiliation," was reported by Kendrick Frazier, "A Scientology 'dirty

tricks' campaign against CSICOP," Skeptical Inquirer vol. 4, no. 3, Spring

1980, pp. 8-10. Some of the FBI-seized documents can be found online at

http://shipbrook.com/jeff/CoS/docs/.

10. See the Wikipedia entry for "Trementina

Base."

11. See note 2. And a case in Reitman's book, which stretches

through-out the book, are of the married Sea Org couples Stefan and Tania

Castle and Marc and Claire Headley. Both couples were split up by the church

and the husbands escaped the church, uncertain they would see their wives

again, but they both successfully managed to help their wives escape.

12. The decision in the Sklar case states: "under both the tax code

and Supreme Court precedent, the Sklars are not

entitled to the charitable deduction they claimed. The Church of Scientology's

closing agreement is irrelevant, not because the Sklars

are not 'similarly situated' to Scientologists, but because the closing

agreement does not enter into the equation by which the deductibility of the Sklars' payments is determined. An IRS closing agreement

cannot overrule Congress and the Supreme Court."

13. The three major lawsuits were RTC v. Netcom, 907 F.Supp.

1361, N.D. Cal. 1995; RTC v. Lerma, 908 F.Supp. 1362,

E.D. Va. 1995; and RTC v. FACTnet, 901 F.Supp. 1519, D. Colo. 1995. Details may be found in the

sources in note 1 and 3; the Wikipedia pages on these three lawsuits are also

comprehensive.

14. Document published on Marty Rathbun's blog (October 23, 2011) and

verified by Tony Ortega at the Village Voice's Runnin'

Scared blog (see note 2) on subsequent days (e.g., http:// blogs,villagevoice.corn/runninscared 12011/10/markebner.on,s.

ph p).

15. See Wikipedia pages for Project Chanology,

Anonymous, and 4chan, as well as in Jeff Jacobsen's article, "We Are

Legion: Anonymous and the War on Scientology".

For updates click homepage

here