It started with a

mere 10 armed men to leave Karachi, the port city in Pakistan, by boat. As they

were nearing the Indian coastline, they hijacked a fishing dinghy and kill four

of the five-man crew. The terrorists then force the last boatman to take them

to the Mumbai coast. Soon over 160 people were killed and hundreds were left

injured.

A lot of the

reporting focused on the above pictured Taj

Mahal Hotel but there were other places in Mumbai where the attackers

spread out to:

It was soon found out

that the ten Pakistani men were associated with

the terror group Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LeT) which

shot to prominence after the December 2001 attack on the Indian parliament. But

one of the reasons why the wounds still run deep is that those who conceived

the attacks have never faced trial. Many believe the secret relationship

between the Pakistani intelligence and the LeT -

which was exposed during the subsequent investigations in India and the US - is

the main reason behind Pakistan's reluctance to stamp out the movement. It is

alleged that because of the support of the security apparatus for the group, no

solid action has been taken against LeT.

The LeT remained Pakistan’s preferred terror outlet when for

example in

2014 the group attacked the Indian consulate in Herat, Afghanistan, on the

eve of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s inauguration. More recently, the LeT has led the campaign in Pakistan to send troops to

fight alongside Saudi Arabia in Yemen. Riyadh is an important source of LeT fund-raising.

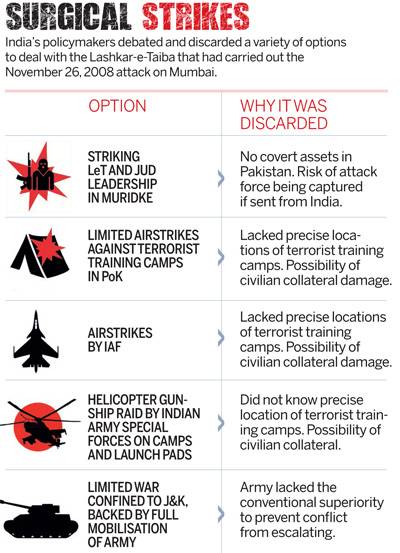

On December 2, 2008,

India's military, political and intelligence leadership seriously deliberated

options that had the potential of triggering a possible fifth India-Pakistan

war.

The options for

retaliation that India debated were known to the United States as well and the

Bush administration sent

senators John McCain, Lindsey Graham and US special representative for

Afghanistan Richard Holbrooke to Islamabad sometime after the attacks which

began on November 26, 2008, to judge the public mood there.

Why it was about Kashmir.

The Mumbai attacks

came as the two countries re-engaged in peace talks to resolve the dispute over

Kashmir. The

militants involved in the Mumbai massacre spoke of abuses in Kashmir, over

which India and Pakistan have fought two of their three wars and where more

than 40,000 people have been killed since the 1980s.

It is generally

accepted that Kashmir is a victim of the disputed division of British India

during the transfer of colonial power in 1947. A border was created on

religious lines, and states with a Muslim majority formed the newly created

Pakistan alongside a predominantly Hindu India. When India and Pakistan became

independent, it was generally assumed that Jammu and Kashmir, with its 80

percent Muslim population, would accede to Pakistan, but Kashmir was one of 565

princely states whose rulers had given their loyalty to Britain but preserved

their royal titles. The partition plan, negotiated by the last viceroy, Lord

Mountbatten, excluded these princely states, which were granted independence

without the power to express it.

Initially the British

create the state of Jammu and Kashmir from a disparate group of territories

shorn from the Sikh kingdom placing it under the rule of a Dogra Raja, and

during the late nineteenth century, they directly intervened in the

administration of the state. The consequent land settlement of the region led

to the breakdown of the state monopoly on grain distribution, the emergence of

a class of grain dealers, the creation of a recognizable peasant class, and the

decline of the indigenous landed elite. Additionally, the slump in the shawl

trade beginning in the 1870s meant that shawl traders were in a state of

financial and social decline by the late nineteenth century. At the same time,

the Dogra state became more interventionist, centralized, and the

"Hindu" idiom of its rule became increasingly apparent.

But contrary to

popular belief, it was not the isolation of the Kashmir Valley that produced

narratives of regional and religious belonging; rather, it was the Valley's

links with the world outside that helped reinforce the poetic discourse on

identities in the mid-eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries.

Rather, the axiom of

Kashmir as the paradise on earth, which even then belied the reality of the

condition of the Valley and its inhabitants, was coined by the Mughal emperor

Jehangir.1

He builds some of the

more scenic architectural marvels of the region, such as the Mughal Gardens and

the Pari Mahal. And the emperor was so enamored of the Valley that he even took

an interest in the concerns and complaints of its people. He dismissed one of

his high-ranking officers, Qulich Khan, then governor

of the Valley (1606-9), on receipt of complaints against him: "O protector

of administration! complainants are many, your thanks givers few/Pour cloud

water on the lips of the thirsty or get away from the administration.” 2

The Mughal era was one of intense cultural

regeneration in Kashmir when Kashmiri poets and ideologues built on existing

cultural forms through contact with poets from the Delhi court and the court of

Persia. Persian became the medium of literary expression, not only for those

who migrated to Kashmir but also for native Kashmiris.

Even as the poets of

the Mughal period glorified the beauties of the Valley, their poetry did not

obscure the realities of the land and the lives of its people. Although clothed

in philosophical terms, the following verse articulates poignantly the curse

of the Valley and its inhabitants:

The path of poverty [fagr] is evident from the road leading to Kashmir: Its very

first step means the renunciation [tark] of the

world. How can one pass this path with ease:

For the very first

condition means relinquishing life? How can a traveler escape this calamity,

Except that a slip of the foot may become a cause of his rescue.3

The land of Kashmir,

as articulated in the works of Kashmiri poets of the Mughal period, may have

existed for the most part only in the imagination of the Mughal emperors and

their court poets, but it is undeniable that its cultural expression informed later

articulations of Kashmiri identities.

If the Mughal period

is seen as the beginning of the end of Kashmiri independence by Kashmiri

historians, the Afghan period is seen as its end. Most historians of Kashmir

agree on the capacity of the Afghan governors, a period unrelieved by even

brief respite devoted to good work and welfare for the people of Kashmir.

According to these histories, the Afghans were brutally repressive with all

Kashmiris, regardless of class or religion. Merchants and noblemen of all

communities were assembled and asked to surrender their wealth to the first

Afghan governor, on pain of death. Kashmiri peasants, Jagirdars,

nobles and merchants alike were buried under the burden of heavy taxation. The

Jizya or jizyah, or the poll tax on Hindus, was revived and many Kashmiri

merchant families fled the Valley for the plains during this period. With the

departure of merchants and with the peasantry avoiding cultivating the land for

fear of exactions, the Kashmiri economy was effectively ruined.

Without detailing the

oppression of various Afghan governors, for there were many, suffice it to say

that the Kashmir Valley underwent a period of immense political and economic

crisis over sixty-seven years of Afghan rule. Despite its near accuracy, this

tale of plunder and woe needs to be qualified through mention of Kashmir's

position at the crossroads of trade routes from the north, north-west, and east

during the Afghan period. The axis of the Mughal empire-the Grand Trunk

Road-was completely redirected by the Afghans. The new route, in the eighteenth

century, circumvented the Punjab and Delhi and from Durrani Kashmir, the

caravans could now reach Peshawar and Kabul without touching Sikh territory.4

This lament for the

just rulers of their land continued through a more explicit Kashmiri discourse

on regional belonging during the rule of the Sikhs, who followed the Afghans in

1819. Maharaja Ranjit Singh, entered into a treaty with the British in 1809

whereby the British agreed to abstain from interference in territories north

of the Sutlej if he gave up a claim on territories south of the river. After

the conclusion of the treaty, Ranjit Singh began his campaigns to conquer

principalities north of the Sutlej and expelled the Afghans from Multan, Dejarat and Kashmir. He valued the Kashmir province not

only for its revenues but also for its strategic position which facilitated his

numerous military campaigns. The Sikh governors deputed to administer Kashmir

on behalf of Maharaja Ranjit Singh were "hard and rough

masters,"(particularly as Kashmir was a considerable distance from Lahore.

More significantly, they consistently followed anti-Muslim policies in Kashmir,

thus subjecting the majority of the population of the Kashmir Valley to severe

hardship in relation to the practice of their religion. The second Sikh

governor, Deewan Moti Ram, ordered the closure of the Jama Masjid in Srinagar

to public prayer and forbade Muslims from saying the azan (call to prayer) from

mosques in the Valley. He also declared cow-slaughter a crime punishable by

death." Lands attached to several shrines were resumed on order of the

state. Sikh governors began the policy of declaring mosques, such as the Pathar Masjid, as the property of the state.

The continuation of

this policy under the Dogras in the late nineteenth

century would provide the fuel for the organization of Kashmiri Muslims as

their leadership took up as a cause the return of state-owned mosques to the

community. The Sikhs thus established a specifically "Hindu" tone to

their rule, setting the stage for the Dogra dynasty which began ruling Kashmir

in 1846. The Sikh rulers did not formulate these "Hindu" policies

specifically for the Kashmir Valley to harass Kashmiri Muslims; they tried hard

to ban the slaughter of sacred cattle in all the lands they conquered. Their

emphasis on asserting Hindu and Sikh beliefs was part of an attempt to

articulate a Sikh identity separate and distinct from that of the Mughals.5

While there is clear

evidence for oppressive conditions under a Sikh rule, it is also important to

remember that historians of Kashmir and European travelers had their own

reasons for presenting Sikh rule in a negative light. Historical evidence

points to the fact that, despite its anti-Muslim overtones, the Sikh rule also

stabilized the economy of Kashmir.

And Kashmiriyat rises to the foremost vociferously in the

historical narrative of the

Dogra period. The Kashmir Valley came under Dogra rule (1846-1947) with the

ominous terms of the

Treaty of Amritsar signed between Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu and the British

in 1846, whereby the British "transfer and makeover forever in independent

possession to Maharaja Gulab Singh and the heirs male of his body all the hilly

and mountainous country with its dependencies situated to the eastward of the

River Ravi including the Chamba and excluding Lahul, being part of the

territories ceded to the British Government by the Lahore State ..."6

Kashmiris, regardless

of their religious affiliations, launched a national movement against the Dogra

This narrative, of course, is prejudiced by its insistence on locating unified,

cohesive Kashmiri nationalist movement, untarnished by religious, regional, or

class distinctions within the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. Furthermore,

it fails to point out that the Kashmin national

movement of the 1930s and 1940s was preceded by a Kashmiri discourse on

identities that focused primarily on defining the religious community, not the

Kashmiri nation. And finally, the narrative on Kashmiriyat

ignores the contradiction that forms the substance of the Kashmiri nationalist

movement: this movement, which supposedly rescued Kashmiriyat

from the jaws of the Dogra regime, based its demands squarely on the

socio-economic distinctions between the two main religious communities in

Kashmir, Pandits

and Muslims. This contradiction is rooted in the story of the political,

social and economic transformations introduced on to the Kashmiri landscape

during the Dogpra period. Although subjects of the

greater British Indian Empire, Kashmiris formulated their identities under the

rubric of the apparatus of legitimacy deployed by the Dogra state, which

continually attempted to balance its definition in terms of the idioms and

instruments of Hinduism and the ideal of non-interference with religions so

dear to the British.

To suggest that a

Kashmiri identity, Kashmiriyat, defined as a

harmonious blending of religious cultures, has somehow remained unchanged and

an integral part of Kashmiri history over the centuries as seen above, thus is

a historical fallacy.

Then, by the early

1930s, the worldwide economic depression had begun to have an impact on a wide

cross-section of Kashmiri society. The slump in trade beginning in 1930 and

fall in the price of agricultural produce led to increased rural-urban

migration. However, the urban factories that had provided jobs to the

immigrants in the 1920s were now in a state of collapse.' Newspaper editorials

from this period lamented the rise in unemployment, the decline of factories

such as the silk factory, and the acquisition by moneylenders

and mahajans of those lands that had been made

over to the peasants as part of the conferral of proprietary rights by the

government.

Although the

government had passed a Land Alienation Act in 1926 to control the transfer of

land by sale or mortgage, which disallowed the transfer of the newly acquired

rights to any but a member of the agricultural classes and prohibited an

alienation of more than 25 percent of any holding for a period of ten years,

the peasants exercised this right in full for the liquidation of debt. These

sales increased the fragmentation of holdings and transferred much of the land

to members of agricultural classes who were not cultivators. This, in turn,

resulted in the reduction of the state's aggregate food supply and difficulties

of feeding a rapidly increasing population. Additionally, it led to soaring

land prices, which the richer classes in the Valley, usually

non-agriculturists, were willing and able to pay.7

Also, events in Jammu

and Kashmir should be viewed in the all-India political context of the period.

Although Kashmir was far removed from the Purna Swaraj resolution adopted by

the Indian National Congress in 1929 and the Civil Disobedience campaigns of

the early 1930s, the people of Kashmir, particularly their leadership, were

greatly affected by the heated political atmosphere in India. By far the most

significant impact by 1931 was the entry of the term communal into the Kashmiri

political arena. From 1931 onwards, Kashmiri politics and politicians, not

unlike their Indian counterparts, would come to be judged on the communal

national gauge. The communal/national dichotomy had been in use in British

Indian provinces since the early twentieth century. In Bengal, for instance,

the gradual distancing of leading Muslim associations headed by Abdul Latif and

Syed Amir Ali from the Indian National Congress in the 1890s prepared the

ground for the use of these dichotomous terms by "nationalist" politicians.

However, their use became more widespread and loaded during the time of the

Swadeshi movement (1905-8). By the end of the first decade of the twentieth

century, Bengali Muslims had begun to discuss defensive interpretations of

communalism in the format of "good" versus "bad"

communalism.8

Finally, in 1931, The

state in general and the Maharaja, in particular, were caught between the

overwhelming upsurge of Kashmiri Muslim public opinion and the rancor of

Kashmiri Pandits at being the objects of sacrifice to placate Muslim demands.9

Apart from the two

communities, the pressure from the British to resolve the crisis was increasing

daily as the Ahrar jathabandi continued in the Jammu

province. The Government of India was sufficiently concerned that the Viceroy

wrote in his telegram to the Secretary of State for India, "So long as

active jathabandi continues, there is cause for

considerable anxiety ... The danger will remain that justly or unjustly Kashmir

will be made a pretext for Muslim organization when this seems likely to serve

the community's [Punjabi Muslims] purpose."10

British troops had

already entered the state and the Resident was pressing the Maharaja to accept

a deputation of outside Muslims to conduct an inquiry into the happenings of

1931. A ruler who had declared in his accession speech that "my religion is

justice" was faced with the prospect of keeping his word. The foremost

issue that the Maharaja ordered the Glancy Commission to investigate was the

"complaints ... in regard to any conditions or circumstances which might

tend in any way to obstruct free practice of any religion followed by any

community in my State."11

He did not, however,

accept the Government of India's view on allowing a deputation of outside

Muslims to conduct an inquiry in the state, so as to prevent demands of a

similar nature by Hindus. (Ibid.)

The Maharaja's

attempts at keeping Kashmir isolated from the outside world had already failed.

Kashmiri Muslim politics continued to be played out as much inside as outside

the state. The leadership of the 1930s made full use of the financial and moral

support of organizations sympathetic to their cause in British India. Further

attesting to the imbrication of politics in British India and Kashmir, the

developments during 1931 and its aftermath, brought with it the language of

inclusionary Indian nationalism into the Valley. "Communal" became

the pejorative term with which to slander one's, political opponents. Although

not in widespread use yet, the term "national" would soon appear as

the foil of communalism.

The emergence of

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah on the Kashmiri political landscape and the foundation

of the All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference illuminate the intricacies of this.But if Sheikh Abdullah had succeeded in introducing

the idea of a Kashmiri nation into the political discourse of the Valley, he

certainly failed in the 1940s to translate this into concrete politics. By the

way there are more than 400 works that wholly or in part examine the 1940s.

Some examples are: Hassnain, Freedom Struggle in Kashmir, Sardar Mohammad

Ibrahim, The Kashmir Saga, 2nd edn (Mirpur: Verinag Publishers, 1990); Devendra Swarup and Sushil

Aggarwal, eds., The Roots of the Kashmir Problem: The Continuing Battle between

Secularism and Communal Separatism(Delhi: Manthan Prakashan, 1992); Verinder Grover, ed., The Story of Kashmir, Yesterday and

Today, 3 vols (Delhi: Deep and Deep Publications, 1995); Hari Jaisingh,Kashmir: A Tale of Shame (Delhi: UBS Publishers,

1996); and Prem Shankar Jha, Kashmir 1947: Rival Versions of History (Delhi:

Oxford University Press, 1996).

However, it is

essential to debunk the view that the re-creation of the All Jammu and Kashmir

Muslim Conference in 1940-1 was a triumph for the forces of Muslim revivalism

in Kashmir, which would ultimately lead to the province's de facto partition

between India and Pakistan. This perspective is an integral aspect of the myth

that the National Conference represented the majority of Kashmiris, a myth that

was perpetuated by the organization itself in the face of increasing opposition

from various sectors of the population of the state of Jammu and Kashmir in the

1940s. Furthermore, according to this view, the Muslim Conference stood for the

ideals of the Muslim League, which was in favor of the creation of a separate

state of Pakistan and the ultimate accession of Kashmir to this Muslim state,

while the National Conference supported the Indian National Congress and stood

for united nationalism. I believe that this is an exceedingly simplistic

reading of a very complicated and, more significantly, evolving relationship

between these four organizations through the 1940s, a subject that has to be

dealt with elsewhere, however.

Since 1947, the

region has been characterized by political repression and economic

underdevelopment plus since then have not been allowed the right to decide

their own future. Thus one could argue that the dispute and the more recent

insurgency that have riddled the region were neither inevitable nor the result

of the clash between a Muslim-majority region and a Hindu-majority

nation-state.

Of the 565 princely

states, 552 agreed to become part of India but the remainder posed problems:

Hyderabad and Junagadh had Muslim rulers but Hindu majorities and were surrounded

by Indian territory. Indian troops occupied the states and overthrew the Muslim

rulers. In Kashmir, a Hindu nobleman, Sir Hari Singh, was the Maharaja, or

governor. Two months after the independence of India and Pakistan, he was still

unable to make up his mind.

The formal accession

of Kashmir to India was announced on 27 October 1947 when Indian troops were

airlifted to Srinagar airport and waged a successful defense of the maharajah’s

forces that came under attack from invading Pashtun

fighters who were driven out into the

surrounding mountains with as the result

a war between Pakistan and India within

three months of their independence.

The United Nations

brokered a peace deal, which left Kashmir with an arbitrary ceasefire line

curling through its territory and divided between the Indian- and

Pakistani-controlled segments. A UN Resolution was passed on 5 January 1948

that agreed the accession of Kashmir to India or Pakistan should be decided

through a free impartial plebiscite. But this was not forthcoming.

In this dirty war

with no front line, Pakistan and India faced each through the people of

Kashmir. At least thirty thousand, perhaps as many as fifty thousand, have

perished since 1990. The involvement of Indian and Pakistani intelligence

agencies is widely assumed to extend to random bombings, which have killed

hundreds of civilians on both sides while mystery surrounds the carnage. No

group ever admits planting the bombs, rarely is anyone caught and rumors of

conspiracy and intrigue circulates. In August 2003, two coordinated blasts

rocked Bombay within minutes of each other. The first was at the stone arch of

the Gateway of India, the second in a crowded jewelry bazaar. At least fifty

people died and more than a hundred were injured. The Indian police said that

local Muslim militants had planted the bombs with the support of Pakistan's

ISI. There was speculation that the attacks were in retaliation for riots in

the neighboring state of Gujarat, which had left more than two thousand people

dead, mostly Muslims. Railways have been easy targets of this covert conflict,

apparently chosen randomly in a bloody tit-for-tat exchange. But in the end the

Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) demand for independence didn't fit

with the ISI's desires; the agency wanted to absorb the state into Pakistan.

One of the more

pernicious consequences of the conflation of polemics and history in the case

of Kashmir has been the denial of citizenship rights to Kashmiris by the

postcolonial nation-states of South Asia. In an irony of history, the

successive postcolonial regimes of the Jammu and Kashmir state rode roughshod

over the political rights of the state's citizens to ensure loyalty and placate

the doubts of the Indian nation-state.

The citizenship

rights of Kashmiris, both Hindu, and Muslim, were thus obfuscated in the

narrative of united nationalism generated by the postcolonial nation-states,

alongside the policies of the regional governments of Kashmir as they strove to

establish their own legitimacy within the national framework.

When The National

Conference, with its avowedly secular and nationalist stance, resorted to the

homogenizing discourse of Kashmiriyat to paper over

the widespread discontent within Kashmiri society, they were much like its

Dogra predecessor. The National Conference, as much as its so-called

"fundamentalist" rivals in the Valley, seized upon the theft of the

strand of the Prophet's hair from the Hazratbal mosque in Srinagar in December

1963 to present themselves as protectors of Islam, in the process whipping up

communitarian antagonisms in the Valley.

It should also be

noted that the demonstrations against the theft provided Kashmiri Muslims with

a deep discontent against the regional and national governments.12

But the situation in

Pakistani Kashmir has not been much better, with the Pakistani delegation

making overtures to the organization while the Indian state decried this as an

act of sabotage, it is clear that Kashmiris were without representation.

For more details click on the various

scenarios below:

scenario 1

scenario 2 scenario 3 scenario 4

scenario 5 scenario 6 scenario 7

The limited options

India had would come once more to the forefront in September 2016 after a

deadly raid on a Kashmir army base that killed

17 soldiers, with about 35 soldiers injured, some critically.

Violent demonstrations

and anti-India protests calling for an independent Kashmir continued with

hundreds of civilians, Indian security forces, and militants killed in attacks

and clashes. After months of heavy-handed Indian military operations targeting

both Kashmiri militants and demonstrations, India announced in May 2018 that it

would observe a cease-fire during the month of Ramadan for the first time in

nearly two decades; operations resumed in June 2018.

1. See G.M.D. Sufi,

Kashir: Being a History of Kashmir From Earliest Times to Our Own. 2 vols. New

Delhi, 1974, vol. i, p. 295.

2. G.L. Tikku,

Persian Poetry in Kashmir 1339-1846, University of California Press, 1971.p.84.

3. G. L. Tikku:

Persian poetry in Kashmir, 1339–1846: an introduction. (University of

California Publications. Occasional Papers. Literature, No. 4.) xi, 98

4. For this period

see Jos J.L. Gommans, The Rise of the Indo-Afghan

Empire c. 1710-1780, 1994, p. 41-2.

5. C.A. Bayly, The

New Cambridge History of lndia, II. 1, Indian Society

and the Making of the British Empire, Cambridge University Press, 1990, p.22.

6. C.U. Aitchison, A

Collection of Treaties, Engagements and Sanads

relating India and Neighboring Countries, revised and continued up to 1929, vol.xu: jams, Kashmir, Sikkim, Assam &Burma, (Calcutta:

Government of India Cent Publications Branch, 192 9, p. 21.).

7. Capt. R.G.

Wreford, Census of India, 1941, Vol. XXII, Jammu and Kashmir (Jammu: Ranbir

Government Press, 1943), 14-15. The state passed a follow-up Land Alienation

Act in 1938, which allowed for the alienation of land only "where the

alienor is not a member of the agricultural class, or where the alienor and

alienee are members of an agricultural class." See Laws of Jammu and

Kashmir, vol. ui (3rd ed. Srinagar: Jammu and Kashmir

Government Press, 1972), 581.

8. See also

"Report of the Resident in Kashmir," June 19, 1931, Foreign and

Political Department, R/1/29/689/1931, India Office Library, London, 5,

microfilm.

9. "Memorial of

Demands presented by the Kashmiri Pandits to His Highness, the Maharaja of

Jammu and Kashmir," October 24, 1931, Ex-Governor's Records 401/1931,

Srinagar State Archives, 3.

10. "Telegram

from His Excellency the Viceroy (Home Department) to H.M.'s SecretaryofState

for India," December 19,1931, Foreign and Political Department,

R/1/29/823, India Office Library, London, 15, microfilm.

11. "Gist of

Orders issued by the Maharaja," Crown Representative Papers of India,

Foreign and Political Department, R/1/29/823, India Office Library, London, 3,

microfilm.

12. See Victoria

Schofield, Kashmir in the Crossfire London and New York, 1996, pp.197-200.

For

updates click homepage here