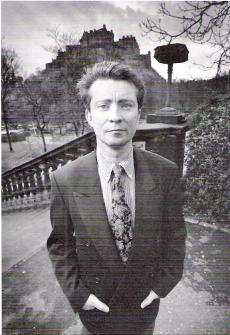

The man who wanted to

be king: The case of Prince Michael of Albany /Lafosse in context

The boy born on 21st April 1958 was the son of two young

middle class Belgian citizens. Doubtless, with all the joy of first-time

parenthood, the father - Gustave Joseph Clément Fernand Lafosse, a shopkeeper,

and the mother - Renée Julienne Dée, a business employee, undertook the legal

registration of the birth. This was done

before the Registrar in the Watermael-Boitsfort district of Brussels. The first

names of the boy were entered into the city record as “Michel Roger”. At the time of the birth the family was

domiciled at “Bruxelles, avenue Jean Sobiesky,36.”

The family and witnesses were not to know that young

Lafosse would one day repudiate this birth certificate and angrily declare it

to be false. He would replace it with

not just one but two crude forgeries, both of which declared him to be “son altesse

royale, le Prince Michael Jacques Stewart, septième Comte d’Albanie.”

Published on an earlier website shortly after

Forgotten Monarchy of Scotland, published in 1998 with the help of Jack

MacDonald, his co-worker Nigel Tranter, and the very able Guy Stair Sainty, Michael ("Stewart") Lafosse was exposed as a

‘pretender’. The Daily Telegraph referring to "an unanswerable

claim" and The Guardian with an article titled "The

man who would be king" soon had interviewed the would be Stewart.

Then, when the Home Office sought clarification from

Michael la Fosse in reference to his use of forged documents for the purpose of

seeking (and receiving) British naturalization and the issue of a British

passport he then left the United Kingdom and via Belgium moved for some time to

Australia. Here Richard Hall (who originally is from Scotland but moved to

Australia) became interested in the pseudo-Prince and (initially

inspired by:) ended up writing an expose which he sent to us for

publication (to be posted in a few days).

The

Royal House of Stuart became extinct in the male line with the death of Henry

(IX) Stuart, Duke of York, Cardinal of the Holy Roman Church and Bishop of

Frascati, in 1807. He had succeeded his elder brother, Charles (III) Stuart,

sometimes known as "Bonnie Prince Charlie", in 1788, on the latter's

death without legitimate issue (he left one illegitimate daughter, Clementina,

who also died without issue). Both were the sons of James (III), Prince of

Wales, only son of James II, King of England, Scotland, France and Ireland,

(illegally) deposed as King of England and Scotland on 10 Dec 1688, and as King

of Ireland six months later, who died in exile in 1701. With the death of

Cardinal Henry of York, representation of the House of Stuart passed to Charles

Emmanuel of Savoy, King of Sardinia. The latter's present heir is Franz, Duke

of Bavaria.

In

naming "Marguerite Marie Therese O'Dea d'Audibert de Lussan" as

Charles' supposed second wife "Prince Michael" begins a pattern of

attributing to people the surnames of their maternal ancestors; Marguerite

O'Dea may have been descended in the female line from the families of Audibert

and Lussan, but she had no right to use these surnames herself. She was not a

member of the great French families of Audibert or Lussan and had no right to

the title "comtesse de Massilan" (see underneath the extensive

comment of our co-worker Richard Hall*).

Prince

Michael also brings together four lines of descent from Prince Charles Edward

Stuart. His grandmother, the Princess de Sedan, descends from the marriage of

Aglae Clementine, daughter of the Duchess of Albany by Ferdinand de

Rohan-Guenene (sic, actually Guemenée), whilst his father the Count of Blois

has two descents from the other Rohan-Albany daughter, both via Prince Louis

Xavier de Bourbon, son of Charles, Duc de Berri, the son of Charles X. His

paternal grandfather descending from Prince Louis' daughter Victorine, and that

grandfather’s wife being a descendant of the Duc d’Aquitaine.

Today,

there are several lines descended from Prince Edward James, Second Count of

Albany. They include the Counts of Derneley and the Dukes of Coldingham.

Foremost, however, in the main line of legitimate descent from Charles Edward

Stewart and his son Edward James is the present Seventh Count of Albany: Prince

Michael James Alexander Stewart, Duc d’Aquitaine, Comte de Blois, Head of the

Sacred Kindred of St Columba, Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Temple

of Jerusalem, Patron Grand officer of the International Society of Comission

Officers for the Commonwealth, and President of the European Council of

Princes. Prince Michael’s own compelling book "Forgotten Monarchy" (a

thoroughly detailed and politically corrected history of the Scots royal

descent) is now in the course of preparation.

The

senior Stewart line goes all the way back to King Arthur’s father, King Aedan

of Scots, on the one hand and to Prince Nascien of the Septimanian Midi on the

other. The Scots descent traces further back through King Lucius of Siluria to

Bran the Blessed and Joseph of Aramathea (St James the Just), while the Midi

succession stems from the Merovingians male ancestral line through the Fisher

Kings to Jesus and Mary Magdalene."

This wholly fictional claim is taken from The Bloodline

of the Holy Grail - The Hidden Lineage of Jesus Revealed by Laurence

Gardner, The Chevalier Labhran de St Germain, and published by Element Books.

It is a complete invention, and cannot be supported by any documents or

historical sources. The alleged genealogy is filled with falsehoods, the most

obvious being that Prince Charles Edward, Charles III, never married

"Marguerite O’Dea d’Audibert de Lussan, Comtesse de Massillan" (1749-1820),

had he done so he would have been guilty of bigamy since he was already married

to Princess Louise of Stolberg, who survived him. Perhaps this name is called

into the equation because the Drummond Dukes of Melfort married into this same

family and inherited the Lussan title. See the extensive comment below.*

The

de la Tour d'Auvergne family, Dukes of Bouillon and Princes of Sedan had become

extinct in the male line in the 1790s, and their inheritance passed to the

Rohan family; "Germaine Elize Segers de la Tour d’Auvergne, Princess de

Sedan" (1908-1992), did not exist (at least not as a member of that family

with those titles). The fact that he apparently does not even know the alleged

date of this fictional marriage - his own grandparents - is an astonishing

admission when it is supposedly by virtue of this alliance that he makes his

ridiculous claim to the British throne! The fact that a wholly fictional son of

the Duke of Berry, "Prince Louis-Xavier de Bourbon" is called into the

equation is further evidence of "Prince" Michael's fantastic

imagination. He also claims a descent from the Duke of Aquitaine (later Dauphin

and then titular Louis XIX), who never actually had any issue by his wife, the

only surviving child of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette.

Seen in context there have been other cases

Like

other such claimants he haunts the world of fantasy royalty and self-styled

Orders. An occuring theme here is also the clash between conventional academic

history and the romantic version of history spread by amateurs and conspiracy

theorists. Today an insurmountable chasm separates the Oxford history professor

writing scholarly papers on medieval agriculture, or pontificating on the

intricacies of French law at the time of Louis XI, and the Internet conspiracy

theorist trying to make a case that William Gladstone was Jack the Ripper or

that Adolf Hitler escaped the Berlin bunker and lived to a ripe old age. But in

the nineteenth century the gap between conventional and romantic history was

much narrower. Widely read, eccentric dilettantes devoted their lives to

solving great historical mysteries and sifted through vast quantities of

contradictory evidence; both Naundorff and Kaspar Hauser recruited some of

their warmest supporters from their ranks. Not until the 1950s could a clear

and growing impatience with the survivalist rumors be noted among French

academic historians, although their books on Louis XVII did little to put the

national myth of the lost dauphin to sleep. In Germany, the Hauserians

maintained the upper hand even longer. Hermann Pies and Johannes Mayer, whose

herculean efforts to prove that Kaspar was the prince of Baden were reviewed

earlier, were both private scholars. The rationalist German academics who

wanted to point out the many shortcomings of the Hauserian propaganda had

difficulties even getting their works into print. In some of the other

historical cases of disputed identity, where the amount of conflicting evidence

was much less, modern historians have succeeded in refuting the claims of some

nineteenth-century great pretenders. The claim of Olive Serres was crushed by

the 1930s, and that of Helga de la Brache by the 1970s. In addition, the

arguments presented by Professor Roe, and reinforced by myself in this book,

clearly refute the notion that the Tichborne Claimant was Roger Tichborne.

For

example there were hundred’s of Dimitri’s (son of a Russian Czar) and a

well documented 101 “false dauphins” all pretending to be the lost son of King

Lois XVI, all 101 claiming to be the current “King of France,” each with

less or more, followers. Not least of all America had at least five false

dauphins. One German clockmaker, (who found some followers among Saint- Simonianists and

French occultist like Eliphas Levi) the Naundorffists, strengthened their

position during the Third Republic, and actually became a force to be reckoned

with in French politics. There were, at the time, Bourbon legitimist,

Orleanist, Bona partist, and Naundorffist deputies in the French parliament,

ensuring vigorous debates when the question arose of who had the legitimate

right to the throne. In 1874, Naundorff's sons petitioned that their father be

recognized as Louis XVII, but they lost their case. Today they have a presence

on the internet, still pursuing their (long

proven to be false) claim.

There

is no doubt that the hair and bone originated from Naundorff, and his exposure

as an impostor agrees well with the available historical evidence. The study of

the dauphin's heart has the benefit of a positive match, indicating that it

comes from a matrilineal descendant of Empress Maria Theresia, the mother of

Marie Antoinette. But in this case the available historical and medical evidence

is much less clear than in that of Kaspar Hauser; there are numerous puzzling

circumstances indicating the possibility of a substitution of children,

although not an escape. The impact of the DNA evidence is reduced by the fact

that the heart several times shared a repository with other Habsburg hearts,

and possibly also with the heart of the first dauphin, Louis Joseph, but this

may just be my wish to believe that at least one proper historical mystery of

disputed identity remains for future generations to ponder.

Also

in the case of the famous (due to a number of Hollywood movies and TV series)

Anna Anderson, the Romanov mitochondrial DNA did not match that from a hair

sample and an intestinal biopsy taken during life. In the 1920s and 1930s,

there had been speculation that Anna was in fact (and most probably correct), a

Polish factory worker named Franziska Schanzkowska. One of Schanzkowska's

sisters had claimed Anna as her kinswoman, but Anna had regally dismissed her.

It turned out, however, that mitochondrial DNA from a tissue sample from one

of Schanzkowska's family members matched that of Anna Anderson. Thus it

can be concluded that, like Naundorff, Anna Anderson was an impostor. But the

books and films about the pseudo-Anastasia have made her famous, and people

still want to believe her story. They speculate that the KGB faked the tsar's

remains or that the CIA switched biopsies in the hospital, and some Internet

homepages still uphold her claim. (M. Stoneking et al. in Nature Genetics 9,

1995, 9-10; plus the missing bones were announced to have been found see

BBC News online, May 25, 2002).

Of

course just like with all other examples that could be cited (ranging into the

thousands), there were more than one Anastasia claimant. In the years after the

Russian revolution, bogus grand duchesses and tsarevitches appeared in every

Siberian town. Since World War II, there have been at least ten Anastasias:

three in Britain, one in Tokyo, one in Russia, and one in Montreal. One

American claimant appeared in Rhode Island in the 1960s; another ran the

Anastasia Beauty Salon in Illinois. The only one of them to achieve even a

small fraction of Anna Anderson's fame was Eugenia Smith, who wrote her

memoirs in 1963 and passed a lie detector test arranged by Life magazine. Her

story was unconvincing however, and when asked to provide a DNA sample in the

mid-1990s, she refused. The ten Anastasias had no shortage of sisters to

choose from; there were at least three claimants for each of the titles of

Grand Duchesses Olga, Maria, and Tatiana. Eugenia Smith's book was

Anastasia, New York, 1963; other mystifications are discussed by M. Occleshaw,

The Romanov Conspiracies, London, 1993).

Of

the eight men claiming to be Tsarevitch Alexis (the younger brother of

Anastasia), the most prominent was the Polish secret service officer Colonel

Michael Goleniewski, who defected in 1960 and went to the United States. A

brazen impostor, he claimed that his father the tsar had lived on in Poland

until 1952 and that three of his sisters were still living there. Eugenia

Smith, the bogus Anastasia, was his fourth sister, he claimed, and they had a

touching reunion, only to denounce each other a few weeks later. Goleniewski

died in New York in 1993, sharing his "sister" Eugenia Smith's

distrust of DNA testing to the last. (See V. Retrov et al., The Escape of

Alexis, 1998), and M. Gray, Blood Relative, 1998).

A

well-known twentieth-century lost heir is the infant son of Colonel Charles

Lindbergh, kidnapped for ransom in 1932. What was purported to be his dead body

was later found and identified by the family. The carpenter Bruno Hauptmann was

convicted for the kidnapping and murder and executed in the electric chair.

Although strong forensic evidence links Hauptmann with the crime, some people

have continued to doubt his guilt. Conspiracy theories have abounded: had

the baby been kidnapped and murdered by the Mafia, by the gang of Capone,

by his aunt Elizabeth Morrow, or even by Charles Lindberg himself ? More

audacious still is the suggestion that Charles Lindberg Jr. was not killed at

all. It has been claimed that a gang of bootlegers from New York used to ship

their liquor on the back roads near area searched by the police looking for the

Lindbergh baby. Fed with being stopped and searched by the police, they

prepared a baby’s corpse and planted it in the woods to get the police off

their trac and enable them to ply their trade as usual.

In

the 1970s and 1980s, several claimants surfaced, attractec the Lindbergh

millions; they had implausible tales to tell. The factory worker Kenneth Kerwin

claimed to have recalled being kidnapped a child in a session of hypnotic

regression; he could also describe Lindbergh nursery in some detail. But his

adopted father told the journalists that Kerwin was certainly not a Lindbergh.

His claim was aided by the fact that whereas he had brown hair and dark eyes,

Ch. Lindbergh Jr. had been blond and blue-eyed. The fellow claimnant Lome

Huxted also "remembered" his true identity during a hypnotic session

and even passed a lie detector test. Following Naundorf’s precedent, he had his

name legally changed to Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. In the 1990s, he was

still pursuing his claim.

Another

well-known Lindbergh claimant is the Connecticut businessman Harold Olson. His

story was that Colonel Lindbergh had been a leading crime fighter in the

Prohibition era. The imaginative Olson claimed that Lindbergh used to fly his

airplane over New Jersey to mark the coordinates of any plume of smoke that

would indicate an illicit distillery for moonshine whisky and then called in

the police. Some of the bootleggers decided to get back at Lindbergh by

kidnapping his son. Framing Hauptmann as the kidnapper was part of the plot.

They then used the Lindbergh baby in a blackmailing scheme to spring Al Capone

from prison, but Lindbergh chose to sacrifice his son rather than to be

responsible for this notorious gangster's being set at large. The ending of

this preposterous story is that after their plot had failed, the gangsters no

longer had any use for their hostage. With uncharacteristic clemency, they did

not kill him, but instead were kind enough to hand him over to caring foster

parents. Both Olson and Kerwin were still active in 2003, along with at least

five other pretenders, one of them a black woman from Oklahoma, who told the

journalists a wild story of skin dyes and sex-change operations. The pretenders

demand DNA testing, but the Lindbergh family has ignored them.

In

fact if not all, royal families have had their fair share of bastard children.

In Britain, King Charles II was notorious for his many amours with various

ladies at his merry court; more than a few noble families can boast royal blood

as a result of the king's attentions to their forebears. As we have seen,

George Ill's brothers and sons also sowed their wild oats freely. A bastard

child of a royal personage can claim neither title nor inheritance, but the

situation changes completely if it can be proved that the king or duke secretly

married the mother. The legend of Hannah Lightfoot is the most famous example

of this. Although there was a preexisting London tradition about the prince and

the fair quaker, it is clear that much of the publicity about the case in the

1820s was due to the activities of Princess Olive, who herself claimed royal

descent from another secret marriage. Another curious example of a "secret

marriage" mystery comes from nineteenth-century Sweden. King Gustaf IV

Adolf of Sweden, who reigned from 1792 until 1809, was a feeble

creature-wrong-headed, incompetent, and bigoted. The only redeeming elements in

his character were his heartfelt religiosity and high moral values. His

disastrous foreign policy ran the country into war with Russia, resulting in

the loss of the province of Finland to the armies of Tsar Alexander L. Not long

thereafter, the king was dethroned and exiled to Germany. There he underwent a

complete personality change; he divorced the queen, drank and reveled to

excess, slept with many prostitutes, and left a trail of illegitimate little

princes and princesses all over Germany. In the meantime, the French marshal

Jean Baptiste Bernadotte was elected king of Sweden; after his death, the

throne was inherited by his son Oscar 1. But at this time a strange woman with

aristocratic looks and demeanor appeared in Stockholm. She called herself Helga

de la Brache and claimed to be the legitimate daughter of Gustaf IV Adolf and

Queen Fredrika, who she alleged had briefly reconciled and secretly remarried

during the exiled king's travels in Germany. Queen Fredrika was a princess of

Baden, and this would have made Helga de la Brache the cousin of Kaspar Hauser,

if both their claims had been genuine. Many upper-class people in Stockholm

accepted Helga de la Brache as a princess of the old Vasa dynasty, and King

Oscar himself gave her a pension and paid off her debts. She was called the

Ghost of the Kingdom of Sweden, since it was believed that she had dangerous

knowledge that might even enable her to claim the throne. A gloomy,

hypochondriacal character, this Scandinavian pretender wholly lacked the dash

and vivacity of Princess Olive. In the 1870s, a clergyman looked into the

Ghost's past and exposed her as Aurora Magnusson, the daughter of a poor,

drunken customs constable. The king stopped her pension, and the Ghost died

impoverished in 1885. Later research has supported the conclusion that she was

an impostor.

The

"Sickert legend," well known to students of Jack the Ripper and his

crimes, is yet another variation on the "secret marriage" theme.

Since the 1970s, the artist Joseph Sickert claimed that the duke of Russians,

since several similar tales were current at the time. One told that Alexander's

wife, Empress Elizabeth, did not die in 1826; rather, she also faked her death

and lived on for more than a decade as Vera the Silent, a humble nun in

Siberia

Charles

XII, Sweden 's famous warrior king, was shot dead, quite possibly by his own

men, in 1718. But many Swedes refused to believe that he was really dead. There

were tales that the king was walking the countryside, disguised as a tramp, to

find out whether the people still supported him after eighteen years of war and

carnage. In 1721, a claimant appeared in Dalecarlia and managed to convince

quite a few people he was Charles XII. When arrested by the authorities for

inciting rebellion, he confessed that he was an apprentice goldsmith named

Benjamin Dyster. Another allegedly immortal Swedish royal was Prince Gustaf, the

son of the aforementioned Oscar I, who supported Helga de la Brache. He was

very popular, and there was much consternation when he suddenly died in 1852,

at the age of just twenty-five, having been healthy and fit. Rumors soon spread

in Sweden that the prince had faked his death, since he had fallen madly in

love with a Russian countess, whom his family had forbidden him to marry. There

were even alleged sightings of the prince, living abroad with his new wife. In

reality, there is little doubt about Prince Gustaf's death. (P. Hallstrom,

Handelser (on Prince Gustaf), Stockholm, 1927, p. 260).

More

mysterious is the death of Archduke Johann Salvator of Austria, presumed to

have been lost at sea in 1890. A feckless, dissatisfied character, he had

changed his name to Johann Orth, married an opera dancer, and denounced his

noble titles the year before. He aspired to become a merchant mariner,

purchased a large sailing ship, and took it for a lengthy cruise to South

America. The impetuous archduke was last seen in La Plata, where he dismissed

the ship's captain, took command himself, and left for Valparaiso. He never

arrived, and no trace of his ship was ever found. His mother refused to believe

that he was dead. Rumors had it that he had faked his own death to escape into

obscurity, and he was sighted as a monk in Spain, a lumberjack in Uruguay, a

playboy in Biarritz, and a polar explorer on his way to the Antarctic. (J. G.

Lockhart, Here Are Mysteries, London, 1927, pp. 33-64).

The

United States has no kings, queens, and nobles to spin legends around, but the

"immortal king" legend nevertheless makes its appearance in American

culture. Probably the best-known example is the case of John Wilkes Booth, the

assassin of Abraham Lincoln. Conventional history states that Booth was shot

dead at Garratts Farm, Virginia, on April 26, 1865, twelve days after killing

Lincoln at Ford's Theatre, in Washington. But speculation has been rife that

the assassin managed to escape or that the body of another man was given out to

be that of Booth as part of a larger conspiracy. There were also rumors that

Booth was alive long after 1857. One had it that he became an actor in San

Francisco, another that he kept a saloon in Granbury, Texas, and a third that

he went to Bombay, where he was last heard of in 1879. In 1903, in Enid,

Oklahoma, a man named David George confessed on his deathbed that he was really

John Wilkes Booth. Although some people objected that he was much taller than

Booth and had blue eyes whereas Booth's were black, the Memphis lawyer Finis L.

Bates bought the corpse, had it mummified, and set out to exhibition the

circus. Bates wrote a book to prove his mummy was really that of John Wilkes

Booth, but he was much ridiculed and died penniless in 1923. The later career of

the mummy was as adventurous as that of the heart of the Temple Child: it was

bought and sold, seized for debt, chased out of town for not having a license,

and at least once kidnapped for ransom. It remained a steady earner throughout

its long sideshow career. In the 1930s, it was x rayed in an attempt to prove

it was really Booth's, but results were inconclusive. Many Texans saw the Booth

mummy on the carnival circuit during the 1930s and 1940s; it was exhibited as

late as 1972, but its present whereabouts are unknown. On the immortal Booth,

see F. L. Bates, The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth (New York, 1908),

1. Forrester, This One Mad Act (New York ,1937), and Furneaux, Fact, Fahe or

Fable, pp. 12-28. The story of the mummy is in Dallas Morning News, of April

10, 1998. A good recent book on the Lincoln assassination, E. Steers Jr., Blood

on the Moon (New York, 2001), gives the stories of Booth's escape little

credence.

Booth

is not the only notorious American to be credited with amazing powers of

survival. As a part of the glorification of nineteenth century gunslingers and

twentieth-century gangsters, legends of immortality have cropped up about quite

a few of them. Jesse James was not killed in 1882, but lived on in Granbury,

Texas, until his death in 1951, at the ripe old age of 103. Billy the Kid lived

nearby and attended Jesse's 1 02nd birthday party in 1949. Butch Cassidy and

the Sundance Kid did not die in Bolivia, but went back to the United States and

led a comfortable life for many years. The notorious outlaw and gunslinger Wild

Bill Longley cheated the hangman in 1878 and lived on for forty-five more years

as the quiet family man John Calhoun Brown in Iberville Parish, Louisiana. It

was not the gangster John Dillinger who was killed in Chicago in 1934 but his

double, and the real Dillinger lived on into the 1960s. Professional historians

have marveled at these legends, which have very little foundation in fact, but

this has not kept them from gaining a fanatical following among various enthusiasts.

Longley's execution was witnessed by four thousand people, three doctors

declared him dead, and the sheriff personally nailed the coffin shut. Yet the

interest in proving that Wild Bill had survived was such that an exhumation of

the gunslinger's skeleton was made in 2001. Its DNA matched that of one of

Longley's descendants. (Houston Chronicle, June 14,2001).

Science

has also disproved the ridiculous myth about the centenarian Jesse James: the

1882 remains were exhumed, and its mitochondrial DNA matched that of two of

Jesse's descendants. (APC news April 8, 2000; A. C. Stone et al. In Journal of

Forensic Sciences 46, 2001 pp. 173-76).

There

are several twentieth-century examples of the unexpected death of a famous

public character triggering the creation of a similar myth. When Lord

Kitchener, the secretary of state for war, was lost at, sea in 1916, rumors

spread that he lived on as a captive, having been taken to Germany in a U-boat,

or that he had become a hermit living on an isolated island. When Amelia

Earhart, the celebrated aviator, disappeared in 1937, rumors started to fly

that she had been captured by the Japanese or that she had faked her own death

to escape from the public eye, finally ending up in a New Jersey retirement

home in the 1970s. On Kitchener, see Lockhart, Here Are Mysteries, pp. 227-51,

and D. McCormick, The Mystery of Lord Kitchener's Death (London, 1959). On

Amelia Earhart, see J. Klass, Amelia Earhart Lives (New York, 1970), and Rife,

Premature Burials, pp. 78-89.

The

case of Elvis Presley has many of the typical components of the "immortal

king" legend. It has been alleged that, like Alexander I of Russia, the

king had become tired of fame and riches and wanted to withdraw from the world.

As the duke of Portland was presumed to have done, he had a wax effigy made,

complete with large bushy sideburns, to persuade the many fans attending his

lying in state in Memphis that he was really dead. The coffin was also presumed

to contain portable refrigeration equipment to prevent the wax dummy from

melting in the hot weather; the result was that the ten pallbearers were

groaning under its weight as they struggled to carry it to the grave. (G.

Brewer-Giogio, Is Elvis Alive?, 1988, and Rife, Premature Burials, pp. 129-33).

The madcap speculation that J. F. Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe are still alive,

or that Jim Morrison (of the Doors) and John Lennon faked their deaths to

escape into obscurity, is in the same vein as the tale of the immortal Elvis.

Another well-known example of an "immortal" modern celebrity is

Diana, Princess of Wales. Her tragic death in Paris stunned the world, and it

did not take long for urban legends to grow about what really happened in the

tunnel underneath the Seine where the Mercedes carrying the princess and her

entourage crashed in 1997. Conspiracy theories have abounded. Had she been

murdered by the British secret service for wanting to marry her

"unsuitable" lover Dodi al-Fayed, the son of Mohammad al-Fayed, the

owner of the famous Harrods department store in London? Or had the queen and

the duke of Edinburgh decided that she had to be killed, for Prince Charles to

be able to marry his longtime paramour Camilla Parker Bowles? Another

conspiracy theory was that the princess had decided to fake her own death. Like

Alexander I of Russia and Elvis Presley, she was supposed to have tired of

being chased by the media, and decided to retire to a quiet life with young

al-Fayed. There have been alleged sightings of Diana in Hong Kong and Japan,

and conspiracy theorists have presumed that she lives with al-Fayed in an Asian

island paradise. This leaves unexplained why she has not contacted her two

sons, but there has been speculation on the Internet that she visited them

incognito in the guise of a royal nanny, after having undergone extensive

plastic surgery to change her appearance. (More realistic, is the recent movie

by Stephen Frears “The Queen,” with Helen Mirren and and James Cromwell).

Then

there is the of legend of the mysterious simpleton-a child or young adult who

suddenly appears out of nowhere, unable to explain his or her history and

origins. The mysterious simpleton is taken care of by the kindly local people,

but there is soon speculation that he or she must be someone of very high

birth, who has been rendered unable to enjoy the privileges of nobility by

accident or by stratagem. The mystery of Kaspar Hauser is the most famous

example of this type of legend, but by no means the only one. In 1776, a young

woman was begging in the villages near Bristol. A beautiful, fragile-looking

creature, she was obviously of superior breeding. She refused to live in a

house, preferring to sleep in a haystack just outside the village of Bourton.

This singular habit made "Louisa, the Lady of the Haystack," a

well-known local curiosity. (G. H. Wilson, Eccentric Mirror 3, no. 2,1807, pp.

1-36).

She

could speak good English, although it was noted that she was obviously of

foreign birth. Louisa's friends advertised widely in German, Austrian, and

French newspapers to find out whether any well-bred young lady had been lost in

either of these countries, but they received no replies of interest. Louisa's

mind became increasingly feeble and clouded, and she was finally incarcerated

in a lunatic asylum. But in the 1780s a pamphlet appeared in the French

language, describing how a certain Count Cobenzel, the Austrian minister at

Brussels, had been charged with taking care of a mysterious young lady. She had

been brought up by two old women in an isolated house, but was sometimes

visited by a handsome officer who showed her much kindness. Once, in the

Austrian embassy, she fainted dead away when she recognized her benefactor in a

large portrait-a painting of the late Emperor Francis of Austria.

After

traveling on to Bordeaux, she became known as Mademoiselle La Fruelen and

received generous financial support from wealthy noblemen. Her great likeness

(but so is that of Helen Mirren in the above mentioned movie) to the late

emperor was remarked upon by Count Cobenzel and others, and caused much gossip

in town. Suddenly, her benefactors withdrew their support, and she was arrested

for debt and taken to the count's house. The dowager empress made public her

belief that Mademoiselle La Fruelen was an impostor claiming to be a natural daughter

of the late emperor. The pamphlet leaves it unstated what means were taken to

dispose of Mademoiselle La Fruellen. Louisa's friends in Bristol at once

suspected that she had lost her reason as a result of her sufferings and been

set at liberty in the English countryside, where her enemies thought no one

would recognize her. Thus the Lady of the Haystacks was none other than the

daughter of Francis I, emperor of Austria. Poor Louisa's clouded mind gave few

clues as to her identity, although her friends questioned her as closely as

Feuerbach and others had interrogated Kaspar Hauser in trying to uncover his

true identity. It was considered significant that she laughed merrily whenever

anyone spoke German and that she said, "That is papa's own country! "

when Bohemia was mentioned in the conversation It is obvious, however, that

Louisa's claim suffers from a similar lad of hard evidence and surfeit of

sentimental speculation as the myth of Kaspar's Baden princedom. There are

hints of the mysterious simpleton also in the strange tale of Princess Caraboo.

In

April 1817, a mysterious young girl appearee in the village of Almondbury, in

Gloucestershire. Lost and penniless she appeared to speak no European language.

She kept repeating the word "Caraboo," and it was presumed this was

her name. The kind people gave her food and shelter and put much effort into

finding out who this mysterious simpleton might be. She dressed in strange

Oriental garb, armed herself with a bow and arrows, and performed wild dervish-like

dances. When the vicar showed her some Chinese prints she appeared to recognize

them. Several experts came to see her to find out which language she spoke, but

the great linguists were confounded by her strange gibberish. To trick Caraboo,

a witty cleric sneaked up behind her and whispered "You are the most

beautiful creature I ever beheld! You are an angel!" When she did not show

any sign of feminine modesty, it was concluded that she was no impostor

Finally, a Portuguese gentleman delighted everybody when he declared that he

understood every word she said. She was Princes Caraboo, a native of a small

island near Sumatra, who had been kidnapped by pirates and sold into slavery,

before escaping and swimming ashore when the ship was sheltering from a storm.

Princess Caraboo lived in comfort at the local manor house and then moved on to

Bath, where she found new admirers. A certain Dr. Wilkinson showed great

interest and persistence in deciphering her strange language and wrote a series

of articles about her in the local newspapers. One of these had the unexpected

result that a landlady named Mrs. Neale appeared, saying that the information

given made her certain the princess was the servant girl Mary Baker, who had

previously lodged in her house. Caraboo confessed that this was indeed the

case. She had been tramping around the countryside with some Gypsies and picked

up their language, which she enjoyed using to confound the linguists. She had

sworn the Portuguese man into her joke, with excellent effect. It was never

divulged what had prompted this remarkable imposture in the first place.

*comment

in reference to the above mentioned "Marguerite Marie Therese O'Dea

d'Audibert de Lussan" Our co- worker Richard Hall who was the first to

unveil the Marguerite Marie Therese O'Dea d'Audibert de Lussan reference wrote:

Although

evidence rules against the existence of a “Comtesse de Massillan,” at least as

presented in The Forgotten Monarchy and certainly not as the second wife of

Prince Charles Edward Stewart, I could not, initially, identify the somewhat

engaging portrait of the “Comtesse.” The author claims that the portrait is the

work of the French Court Painter, Laurent Pechaux (1729 -1812) who, he states,

painted the “Comtesse” in 1785 – the year of her alleged marriage to Prince

Charles Edward Stewart.

Pechaux

was indeed painter to the Stuart Court. His appointment was made by the de jure

King Charles lll following the death of the “Old Pretender” – James. Pechaux performed his first commission by

painting Charles. A further commission

to paint Louise of Stolberg soon after her wedding in April 1772 followed

this. However, no publication on art

history lists “de Massillan” as a subject of Pechaux or anyone else.

The

Picture Credits in Forgotten Monarchy indicate that either the original

portrait, or a reproduction, is located in the frequently cited “Stewart

Achieves.” This repository is variously described as being in Scotland or in

Brussels. According to the author, it appears to accommodate an additional 28

portraits, among many other items of “evidence.” Despite some clearly fabricated identities,

claiming to be of researchers studying the collection, no reputable scholar has

ever even heard of the “Stewart Archives.”

Of the three pictures that could not be identified, I did not deem two

of them of sufficient importance to continue the search. It was the actual

identity of the most crucial of these - the alleged “Marguerite Marie Therese

O’Dea d’Aubert de Lussan, Comtesse de Massillan,” that presented the real

challenge.

The

National Galleries of Scotland became enthusiastic collaborators, as did the

Art Department of the Australian National University and the Australian

National Gallery. Advice was sought and

received from Guy Stair Sainty who suggested that Jean Marc Nattier might be

the artist. He totally rejected the

possibility that the subject was the “Comtesse de Massillan”. I spent some time

trying to identify the complete inventory of the work of Jean Marc Nattier. The

style and period were generally in favor of the artist. However, my own

research and correspondence with galleries and art dealers around the world

failed to deliver a positive identification. Appeals to some French

institutions were particularly unrewarding. None of my queries written in

English were answered. Initially, I was not confident enough to try my hand in

the language of Voltaire and Victor Hugo but with the assistance of a more

gifted family member, we did craft a request, in French, to one institution. The effort had its own reward and I received

a gracious and comprehensive reply.

A

doughty comrade in the search of the truth kindly displayed a copy of the “de

Massillan” portrait on a web site where negative comments on Lafosse had been

made. It should be acknowledged that they were just as often disputed – usually

on other web sites.

We

placed a “Wanted” sign beneath the picture and invited assistance in

identifying her. In due course, this did

attract a French family (there appeared to be three members alternating with

their comments) who claimed that it was the “Comtesse de Massillan” and that

they knew how she was related to the Scottish claimant. We engaged in a number of frustrating

exchanges. The quality of the debate was

not particularly high. I tried stoically to withstand a number of insults of

which being a “bleating sheep” was one of the more original. I was provided

with a collection of papers, mostly in French, which, with the assistance of

yet another family member, we laboriously translated. It was not a profitable exercise. The papers

were mainly irrelevant or came from dubious sources. I shall comment on the

profile of the La Fosse client-base elsewhere.

In

September 2006, I found a reference to an interesting Internet web site - “Art

Watch.” Having declared my interest in

my correspondence with the Director, I hoped that I might find a new direction

in pursuit of the identification of “de Massillan.” Director Michael Daly,

referred me to the Witt Library of the Coultauld Institute of Art, a London

organization that specialized in cataloguing portraits reproduced in

publications. In a remarkably short time

Annette Lloyd-Morgan, the Deputy Librarian provided me with a copy of the

library data card plus a copy of a brief biography of Julie Jeanne Eleanore de

Lespinasse (1732-76) by Dr Richardiere of Paris. It was attached to the back of

the card. The inference was that someone had suggested that the unidentified

female subject was, in fact, a notable French woman of letters.

This

pastel portrait is by Maurice Quentin La Tour. It is displayed in the Musée

Lecuyer in Saint Quentin, France. It is clearly the same portrait presented by

Lafosse as the “Comtesse de Massillan” and claimed to be the work of Laurent

Pechaux. The Musée Lecuyer has no record of permission being sought by “Prince

Michael Stewart of Albany” to reproduce the portrait.

The

Subject. The genuine portrait is titled “Inconnue” (Unknown Women). It is not

known if this is the title assigned by the artist or a subsequent cataloguer. I

favor the latter. Artists generally did not assign a title to portraits. For contemporary viewers, the portrait would

identify itself. It was usually later

that art historians (or sellers) provided a title – sometimes it was not

correct. The files of the Musée Antoine Lécuyer, whilst rather meager, also

have a post card with the reference

- “Mademoiselle de Lepinasse.”

(?) The Director does not know who has

put forward [this] hypothesis. Whilst the apparent lack of confirmed identity

of the subject might give some comfort to those clinging to the hope that the

subject really is the “Comtesse de Massillan,” there is not the slightest doubt

over the identity of the artist, where the work is displayed, or the title by

which it is known and catalogued. There

is also a clear inference that the subject might be Mademoiselle de Lepinasse.

Certainly, the dates of the presence of de Lespinasse and La Tour in Paris

allow for the possibility of contact.

The prominent position of the young woman in Paris society could well

have caught the attention of La Tour. He produced portraits of Rousseau,

Voltaire, Louis XV, his queen, the dauphin and dauphiness, Mme de Pompadour and

Prince Charles Edward Stewart. Artistically and socially, Julie de Lespinasse

would certainly not have been out of place in this company.

A

useful biography of Julie de Lespinasse may be found in the Encyclopedia

Britannica. The relevant elements of this article, which mirrors the comments

of Dr Richardiere, are as follows:

Julie

was born in Lyons in 1732. She was the illegitimate child of Comtesse d’Albon

and was brought up as the daughter of Claude Lespinasse, also of Lyon.

Following her schooling at the local convent school, she became governess to

the children of her mother’s legitimate daughter (Madame de Vichy) who was the

sister-in- law of Madame du Deffand.

Marie

de Vichy-Charmrond, Marquise du Deffand, was a leading figure in French

society, famous for her witty letters to the Duchesse de Choiseul, to Voltaire

and to Horace Walpole. From the beginning of her intellectual life, she

expressed herself to be an unbeliever and a skeptic. At one stage, at the request of her mother,

the celebrated French preacher and bishop of Clermont (Auvergne) Jean Baptiste

Massillon (1663 -1742) was invited to reason with her. Both mother and preacher were to be

disappointed.

Madame

du Deffand was the centre of a brilliant circle of intellectuals in Paris. In 1754, with her sight nearly gone, she

invited the precocious Julie to join her as her as a companion. 10 years later,

and jealous of the young woman’s influence, Madame de Deffand dismissed her and

suffered the indignity of being eclipsed by the popularity of Julie’s own

salon, to which many of Madame’s former circle were drawn.

Meanwhile

Julie indulged her passion for her role as the most sought-after hostess in

Paris. Although not known at the time she also had a passion for letter

writing. It was not until Mme de Guibert

published a collection of these letters in 1809 that the intensity of her

relationships received literary acclaim.

Less discrete was her passion, first for the Marquis de Mora, and then

for the Comte de Guibert. Mora died in

1774. Then the agitation and misery surrounding her affair with the worthless

Guibert resulted in a total mental and physical collapse. She died on 22 May 1776 at the age of 44.

The

Artist. Maurice Quentin de La Tour (1704-1788) was a leading French pastelist.

He was born at St Quentin on the 5th of September 1704. After leaving Picardy

for Paris in 1727 he entered the studio of Spoede - an upright man, but a poor

master, rector of the academy of St Luke, who still continued the traditions of

the old guild of the master painters of Paris. This possibly contributed to the

adoption by La Tour of a line of work foreign to that imposed by an academic

training; for pastels, though occasionally used, were not a principal and

distinct branch of work until 1720. In 1737, he exhibited the first of a

sumptuous series of 150 portraits that became the feature of the salon for

nearly 40 years. In 1750, he was appointed “painter to the (French) king.” In

1746, he was received into the academy. In the following year to that in which

he received the title of “painter to the king”, he was promoted to the grade of

“councilor.” His work had the rare merit of satisfying at once both the taste

of his fashionable models and the judgment of his brother artists. The museum

of St Quentin also possesses a magnificent collection of works which at his

death were in his own hands. La Tour retired to St Quentin at the age of

eighty, and there he died on the 17th of February 1788. He endowed St Quentin

with a great number of useful and charitable institutions. He never married.

His brother survived him, and left the drawings to the town. They are now displayed in the museum.

The

method used by the Claimant in his artistic deceptions becomes even more

obvious when he captions a portrait claimed to be a cousin of Charles Edward’s

second wife. This is the person whom the Claimant alleges was used as “a decoy

when Charles made secret trips to Britain.” By way of comparison, a second

portrait is shown, this time claiming that it is of the genuine Prince Charles

Edward.

It

was not difficult to identify the source of two portraits in The Forgotten

Monarchy. A book by Donald Nicholas was an obvious reference source. It

contains an extensive collection of portraits of “Bonnie Prince Charlie.” One

of them is located with the Irish Dominicans of San Clemente in Rome. It was

once described as a portrait of the Chevalier de St George, by whom this is

meant James the “Old Pretender.” The identity of the artist is uncertain. However, no student of art history would now

regard the subject as being anyone other than Bonnie Prince Charlie, albeit,

far from his bonnie best! All are clearly the same work.

Update 29

Oct. 2006: See next a

detailed overview of the Michael

Stewart-Albany/Lafosse case by our co-worker Richard Hall.

Update 5

Nov. 2006: Review of Michael Stewart-Albany's second new book, and

our co-worker Richard Hall's own extensive book proposal tilted A KING BEST

FORGOTTEN.

Update 12

March 2016: At his side, attached to his belt, he carried a sword,

and in his hands he held a huge wreath of flowers in the red and white colours

of the Polish flag. He appeared disdainful and rather aloof – clearly "a

somebody" – and just behind him strode two rather overweight gentlemen,

also in kilts and sky blue doublets, and covered in every kind of Highland

accoutrement you can imagine, dirks, powder horns, bonnets, sashes, dingly

dangly orders and decoration, and firmly clamped in their right hands, drawn

claymore swords. "Yes,

His Royal Highness Prince Michael of Albany"

For updates click homepage here