One of the U.N.’s great failures has been its inability to end the 5

1/2-year Syrian conflict, which has claimed over 300,000 lives. During the

ministerial meeting, not only did lengthy U.S.-Russian negotiations fail to

restore a cease-fire but the Syrian government announced a new offensive to

retake Aleppo, unleashing some of the heaviest bombing of the war.

“There

might be a Plan B in life but there certainly is no Planet B,” Eliasson

said Monday in wrapping up the General Assembly’s annual General Debate which

was attended by over 135 heads of state and government and more than 50

ministers.

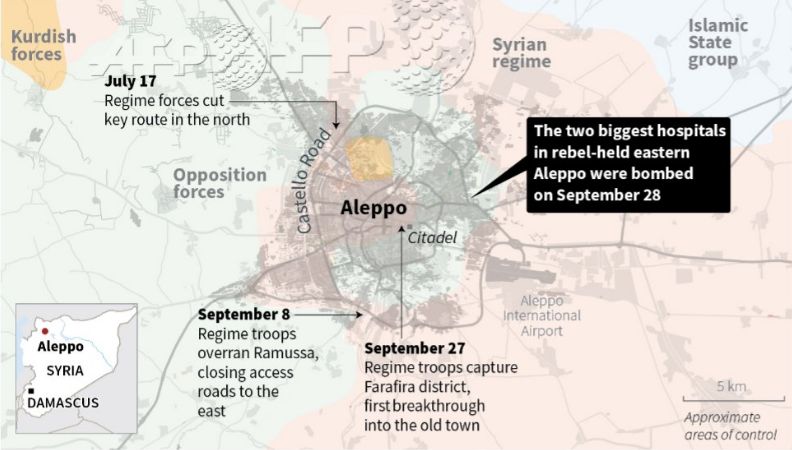

If there was ever any hope of salvaging the latest cease-fire in Syria,

there isn't anymore. Forces loyal to Syrian President Bashar al Assad continue

to attack the rebel-held portions of Aleppo with the support of large and

indiscriminate Russian airstrikes. Today, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry

told his Russian counterpart, Sergei Lavrov, that Washington is preparing to

"suspend

U.S.-Russia bilateral engagement on Syria," including on a proposed

counterterrorism partnership, "unless Russia takes immediate steps to end

the assault" and restore the cease-fire. Moscow, however, is unlikely to

comply; the loyalists remain as determined as ever to retake the city, and the

Russian military is equally determined to assist them in that effort.

Negotiations to de-escalate the Syrian civil war are on the brink of collapse.

But the United States had a good reason to sue for peace in the first

place. Its goal in Syria is, simply put, to defeat the Islamic State. To that

end, Washington backed the Syrian Democratic Forces (a militia composed mostly

of Syrian Kurds), trained rebels to fight the Islamic State on its behalf and

conducted extensive airstrikes on Islamic State targets. The United States also

pressured the Syrian government to negotiate a transition by arming the rebels

who fought against it.

Russia, however, undermined the United States at every turn. With Moscow

reinforcing loyalists on the battlefield, al Assad had no reason to capitulate

to U.S. pressure. And with Moscow even going so far as to bomb areas close to

U.S. positions, Washington was forced to turn its attention away from the

Islamic State and toward the possibility of a clash with Russia, something the

United States was eager to avoid. Russia, too, wanted to avoid outright

conflict. Obstructing U.S. efforts was simply a means to begin negotiations in

which it could serve its broader strategic interests.

The United States was therefore left with two choices: escalate the

conflict by increasing support for rebels and decreasing coordination with

Russia, or concede to Russia. It opted for the latter, keeping the scope

narrowed tactically to Syria and making such important concessions as

cooperating more closely on the battlefield and targeting Jabhat Fatah al-Sham.

For the United States, a cease-fire is still a step toward its goals in Syria.

After all, ending the war denies the extremist group the haven in which it

recruits, trains, procures weapons and ultimately thrives. And though an

agreement was eventually reached to coordinate more closely on the battlefield

and rein in their respective proxies, neither side was able to make it last.

Which brings us to today. The cease-fire has failed, and the United

States won't work with Russia so long as it continues its offensive on Aleppo.

U.S. allies, heretofore content to give the cease-fire a chance, may now start

arming rebel groups in Syria with or without Washington's consent. In fact,

some groups have already received shipments of rocket artillery, and it's

possible that they will be sent man-portable air defense systems to counter

Russian airstrikes.

And so the United States appears to be considering the only other option

Russia gave it: escalation. That is not to say the United States will stop

trying to avoid a clash with Russia; neither side is interested in all-out

conflict. Washington would instead extend greater support to the rebels and

cooperate less closely with the Russians. Still, Moscow may find that

Washington is now less willing to de-escalate after acts of provocation than it

once was. (Here, provocation includes airstrikes on rebels groups in which U.S.

forces are embedded.)

And herein lies the irony of the cease-fire's failure. It was never

meant to end the conflict. It was meant to prevent it from getting any worse.

Now, as trust fades for all those involved, Russia is throwing more support

behind the loyalists, and the United States is throwing more support behind the

rebels. The stakes are even higher now that Turkish forces are operating in

Syria and are pushing southward, approaching both loyalist and Syrian

Democratic Forces fronts. Turkey is in the process of working out its own

deconfliction agreements with Russia, but it is also heavily leaning on the

United States to mitigate potential clashes on the battlefield. Friction in the U.S.-Russia relationship means less

insulation for Turkey on the battlefield. Perhaps most dangerous of

all is the now acrimonious relationship with Russia, which could lead to

dangerous standoffs with wide-reaching consequences.

As for Aleppo's "Grozny moment" as suggested by me earlier, Russia

and its Syrian government allies, could be massacring Aleppo’s civilians as

part of a calculated strategy.

For updates click homepage

here