By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

The new recession

What a wild week. The

turmoil in UK markets escalated far beyond what anyone could have expected, even

after the government revealed a remarkably ill-judged mini-Budget last Friday.

According to top

economist Mohamed El-Erian a U.K. recession

is now inevitable, and the only question is its depth and duration. With

the Guardian writing to days ago: How Liz Truss plunged the UK to

the brink of recession in just one month.

A ‘doom-loop’

triggered by pension funds selling gilts led to a collapse of the UK government

bond market until the Bank of England intervened.

In general, bond

markets all over the world are under pressure right now. But in the British

case, an additional technical factor has contributed to the avalanche-like

sell-off: the pension funds in the U.K. hold lots of government bonds. These

are private pension funds, and they had decided to hedge themselves against the

possibility of interest rates falling. So rather than just being able to pocket

the windfall of the interest rate increase, they needed to unwind a bunch of

hedge deals that covered them against the opposite eventuality. And that is

what was triggering the sales of assets.

Liberal Democrat

leader Sir Ed Davey argued that the government, by waiting until 23 November,

allowed the UK economy to "fly blind" for two

months. "Families and businesses can't afford to wait any longer for

this government to fix their botched, unfair budget," he said.

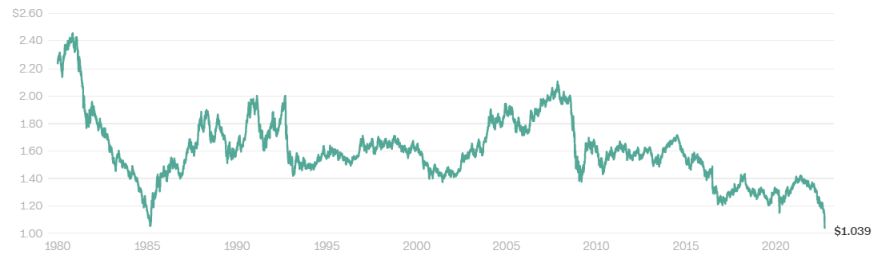

And the falling

exchange rate will hurt. It will immediately hurt the cost of practically

everything in the supermarket. So there will be a pretty direct effect there.

But we’re talking about a relatively modest currency movement. We’re not

talking about the 20, 30 percent fall over a matter of days. We’re talking

about a 10, 15 percent fall, which is still very dramatic for a currency as

significant as sterling, a reserve currency, a minor reserve currency.

The current panic is

huge because it affects the government bond market. And that is a big deal in any

country because that is the foundation of the flexibility of government

finances. And it’s a very big market. It’s trillions of dollars

worth even in the U.K.; in the U.S., it’s $24 trillion. This is a huge

pool of assets in which practically anyone, one way or the other, principally

by way of, say, the Social Security fund or using a pension, is invested. And

so that’s the bit that’s spasming. And in the British case, what’s alarming, is

that the currency movements appear to be closely associated with the spasms in

the bond market, which you don’t want to see. You would prefer those two things

to be independent of each other. When they become coupled, it begins to feel a

little bit like an emerging market situation where investors are, in a sense,

opting in or out of a country, and when they opt out of the government bonds,

they exit altogether. And that’s a worrying sign when that happens. And it can

become self-reinforcing because as the currency falls, the bonds become less

attractive to hold, and so on.

Meanwhile, the

markets have resumed their tailspin despite a rescue for Bear Sterns, the investment bank that has

come a cropper because of its ill-fated expansion into securities based on

sub-prime mortgages. Larry Elliott, the Guardian's economics editor, is

in typically

robust form, arguing

that Americans have been conned.

For updates click hompage here