By Eric

Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Situation in

Thailand

Thailand's Electoral Commission decided on March 4 to allow the

caretaker government to reallocate 20 billion baht ($618 million) from the

central budget to make overdue payments to disgruntled farmers for rice

acquired under the government's controversial rice buying program. The

commission had earlier approved a smaller sum, but it has now cleared the

disbursement of about one-sixth of the total funds due to farmers -- the

government is struggling to find other means to cover the roughly 100 billion baht

that will remain unpaid.

The Electoral Commission had little to gain from withholding funds from

the farmers, which would have been an unpopular decision. The commission has

given the government until the end of May to make up for budget reallocations.

This will be difficult, considering the government has had little success in

raising funds due to its caretaker status and remains focused on the unfinished

elections and a range of judicial cases against it. Still, the decision gives

the government a respite. It may prevent certain farmer groups, mostly in

central Thailand -- and in particular, those that had

threatened to disrupt Bangkok's Suvarnabhumi International Airport -- from

holding additional protests.

While the government's rural base has not withdrawn broad support, the

Pheu Thai party's pro-rural image is tarnished, and it has lost at least some

farmers affiliated with a coalition partner. The commission's decision does not

rescue the caretaker government from the other threats to its hold on office,

but for now it should help the Yingluck administration manage problems in the

rural sector.

Meanwhile, the Constitutional Court is due to decide in March how to

deal with the incomplete Feb. 2 elections. Deliberate interference marred the

polls in certain areas, disrupting voting in 28 constituencies across eight

provinces, mostly in Thailand's southern opposition strongholds. Some

constituencies held elections on March 2 -- these were marked by low voter

turnout -- but in others, voting remains incomplete. In order

to form a government, elections need to produce enough representatives

to meet a quorum. The Pheu Thai party wants the court to allow the Electoral

Commission to carry out the vote under the existing royal decree for elections.

Opponents hope that the court will demand a new royal decree, which would in

effect nullify the Feb. 2 elections and require a new vote. In

order for Pheu Thai to stay in power, it needs to finish the elections

and engage in political horse trading to convene parliament. Even if Pheu Thai

manages to finish elections and form a government, it will be hobbled by the

pending court cases.

Some of the legal cases could result in the ejection of Pheu Thai party

members from public office. The party could even be forced to disband. Past

court decisions have unseated previous parties affiliated with the Shinawatra

movement, notably in 2008. Pheu Thai is therefore planning for a fall from

power and is threatening to hold massive rallies in Bangkok, on the scale of

protests seen in 2009 and 2010. The United Front for Democracy Against

Dictatorship -- the official name of the group known as the Red Shirts -- has

begun mustering forces, holding rallies and practicing rapid deployment so that

its members are ready to descend on Bangkok this spring if necessary. They also

claim to be gathering recruits to build a 600,000-strong movement to enable the

northeast to make a bid for regional autonomy or secession in the event of

exclusion from power in Bangkok. This threat bears watching over the long run.

Since November, the Red Shirts have avoided amassing in Bangkok, a

decision meant to prevent direct confrontation with royalist protesters. Typically Thailand's two factions alternate holding mass

protests, just as they alternate controlling government -- simultaneous rallies

could quickly raise the level of violence. The army has indicated that if large

numbers of Red Shirts enter Bangkok, escalating civil strife could necessitate

more forceful military action or even a coup in the name of preserving public

order.

The military has continued to favor the opposition while avoiding

decisive moves and maintaining the appearance of impartiality. Its position

hardened somewhat, however, after a number of attacks

on protest camps in late February -- in Bangkok and in the provinces --

resulted in the deaths of children and heightened public fears. Army chief Gen.

Prayuth Chan-ocha recently reiterated the military's

option to carry out a coup -- an admonition for restraint by all political

forces, but especially the Red Shirts. The army repositioned its forces in

Bangkok to protect protest camps and major institutions such as the

Anti-Corruption Commission that are likely to come under threat. It is also

weighing the option of arming soldiers with firearms, since they so far have

mostly used batons. These actions highlight the military leadership's broad

sympathy with the opposition, though it continues to maintain its distance from

all political players and retains the option of condoning a Pheu Thai

government under certain circumstances, as it did from 2011 to 2013.

Thailand remains in limbo for now, but pressures are building across the

political landscape toward some sort of compromise. Failure to achieve such a

compromise could spark a new confrontation. While the government wishes to

complete the election and form a new parliament, the opposition benefits from

drawing out this period of uncertainty, preventing the government from

exercising its powers in full -- especially from implementing the 2

trillion-baht stimulus package -- and sapping the administration of support.

Indeed, the opposition has succeeded so far in trammeling the ruling party

without overthrowing it, which would inevitably trigger a backlash. It can be

expected to continue this strategy, which means that its sympathizers in the

military and the judiciary may continue to refrain from decisive moves.

Thailand is dealing with a combination of farmer protests, controversial

government attempts to get financial support from state-owned banks, a spike in

political violence against royalist protesters, military redeployments in

Bangkok, a Red Shirt buildup in the provinces and pending court cases against

the government. The circumstances indicate that Thailand's two main factions

are raising the stakes even as they sit down to negotiate.

A compromise that allows Pheu Thai to stay in power is possible. It

would probably need to include guarantees that the party will not bring former

Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra back from exile or alter the constitution to

entrench its power. But a continued push by anti-government forces to oust this

government seems more likely. This would open a new chapter of unrest, since

the Red Shirts seem prepared to respond. The opposition may at least be able to

draw out the current impasse beyond the springtime, during which rural farmers

could join rallies in Bangkok.

The Root of the Protests

The foundation for the ongoing protests was laid after the Pheu Thai

party’s repeated attempts to push forward several constitutional amendments,

including the recent one that would make the Senate a fully elected body in order to push forward Pheu Thai’s political agenda and a

controversial amnesty bill. A key component of the government’s proposal for

what it claimed to be a national reconciliation, the amnesty bill is widely

said to be an effort to bring Thaksin back into the country from exile and to

strengthen Pheu Thai’s hold on power. Thousands of protesters took to the

streets when the bill passed the lower house in late October, leading the

ruling party to withdraw the bill. Meanwhile, the Constitutional Court rejected

the constitutional amendment in mid-November.

Instead of quelling what were relatively limited protests, the

opposition decided to capitalize on the reaction against the government and

fomented massive demonstrations. The focus of the protests shifted from

blocking the bills to ending “Thaksin’s regime.”

Although the protests have momentum, the opposition’s immediate goal of

bringing down the government will face two major challenges in the next couple

of days. First, it is important for the opposition to bring the military on

board if it is to oust the sitting government. Protests and violence have been

a centerpiece of the country’s political dynamic since the 2006 coup against

the Thaksin-led government, and the judiciary, military and monarchy have

repeatedly intervened. An open military intervention would be the last resort

if violence reaches an extreme, particularly

considering the ruling party’s widespread popularity and moderate progress in a

rapprochement with the royalist-allied military. Despite its past

interventions, the military may be more willing to tolerate a range of

political reversals without directly jeopardizing its own power and prestige.

In the meantime, the opposition’s second challenge will be trying to keep the protests strong. The king’s birthday

weekend from Dec. 5 to Dec. 8 – traditionally a time for celebration and a time

when political moves are seen as disrespectful – is expected to dampen the

enthusiasm for protests.

Even before the current crisis, Thai politics have been deeply

polarized. The geographic, social and economic problems that have repeatedly

brought the country to an impasse have not gone away, and the issue of royal

succession always simmers beneath the surface.

What formed the backbone of Thailand’s contemporary political history –

the antagonistic regional divisions between Bangkok and the northern regions –

was manifested by the rise of the populist Thaksin in the late 1990s. Thaksin’s

massive popularity among the rural poor – especially those in the north and

northeast, which together make up more than half the country’s population – and

his attempts to manipulate political institutions in his favor were seen as a

direct threat to the traditional political establishment in Bangkok, whose

power rests on the military, civil bureaucracy and the royal families.

Thai politics since the 2006 coup have repeatedly been consumed by the

struggles between Thaksin’s proxy parties and anti-Thaksin forces. These

struggles have directly led to several rounds of political crisis and the end

of three successive governments. The popularity of Thaksin’s sister, Yingluck,

and her campaign for national reconciliation had brought relative stability to

the country for the past two years. However, facing the threat of lost

influence, the traditional establishment has not wasted time in

bringing pressure against Yingluck’s government.

Beneath the political roots, there has been a growing economic challenge

during Yingluck’s two years in office. Thailand has made remarkable progress

with sustained economic development, but economic growth and public services

have been largely concentrated in the central region and Bangkok, while the vast majority of the population working in agriculture

and informal sectors has little access to social welfare. Such inequality has

exacerbated social tensions and increased the public demand for inefficient populist

policies.

Moreover, with Thailand’s exports, which accounted for 60 percent of the

country’s economy, faltering amid the global recession and China’s slower

growth, the need to harness the rural population grew. Lower exports also were

an opportunity for the opposition to point to Yingluck’s many inefficient

populist policies and her controversial political agenda. Falling exports have

strained the state budget, which was already beset by a failing rice subsidy

and massive infrastructure investment. Now the country is facing a growing

credit bubble and long-lasting economic slowdown, which will only worsen with

the political crisis.

Struggling for Relevance

As an important security ally of the United States, Thailand was likely

to play a major leadership role in the region at a time of renewed U.S.

engagement in Asia. However, Bangkok's political uncertainties and concerns

about the civilian-military balance appear to have hampered the U.S.-Thai

relationship and have forced Washington to look for other partners, such as the

Philippines, Indonesia and Singapore, and to develop better relations with less

traditional partners such as Vietnam.

With the United States now placing less emphasis on its relationship

with Thailand, the country is accelerating its pursuit of more vibrant ties

with China, which perceives Bangkok as a strategic pillar in its expanded

outreach in Southeast Asia and as a potential corridor as it builds up its

maritime sphere. Under Yingluck's government, China has discussed building a

high-speed rail line from Bangkok to Nong Khai as well as various investment

pacts. But the latest disruption also reminded Beijing that its strategy could

again be threatened if the current government cannot retain power.

While all this is going on, Thailand is faced with the strategic opening

of Myanmar, Thailand's historical rival to the west, and growing competition

with Cambodia in the east. With the rest of the region prepared to capture the

benefits of its newfound significance, Thailand may

find itself being left behind.

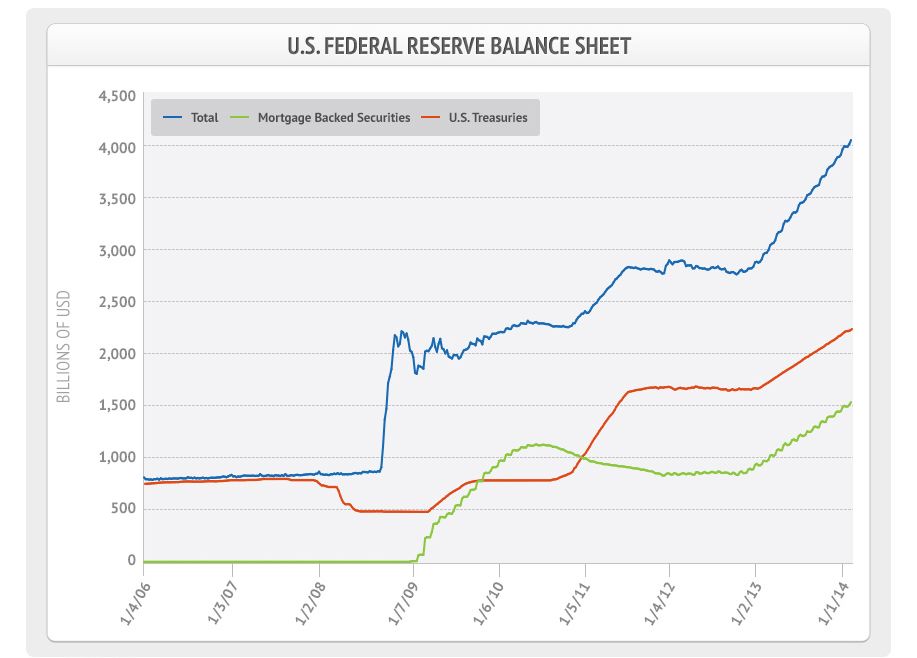

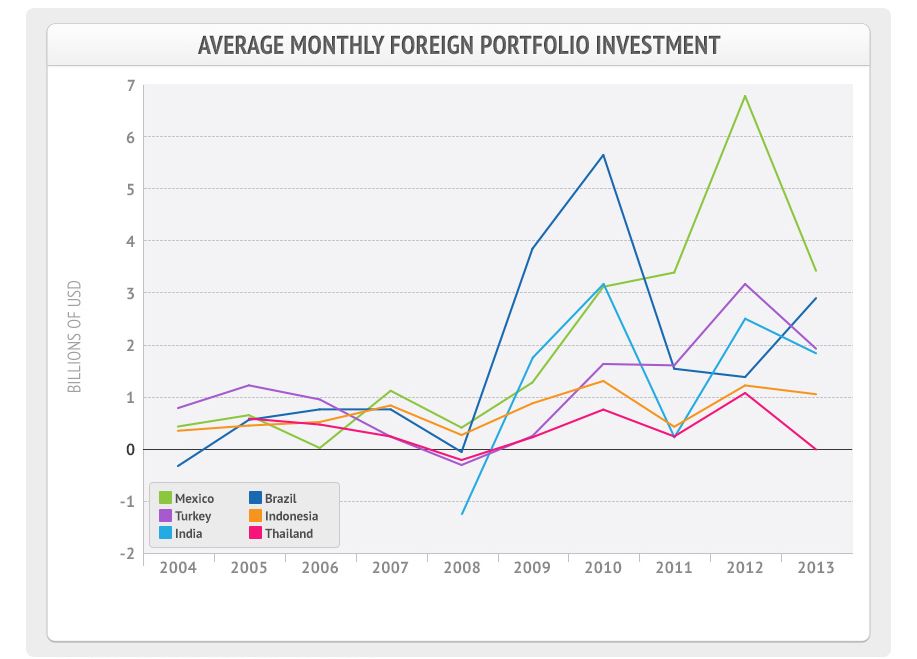

Average Monthly Foreign

Portfolio Investment:

Earlier article about

Thailand

Political and Economic

Volatility in other Important Markets

Turkey

Turkey's ruling Justice and Development Party (abbreviated in Turkish as

AKP) came into power on the heels of a major

banking crisis in 2001, ushering in more than a decade of relatively stable

economic growth. With the AKP's rise also came

the sidelining of the republic's wealthy secular elite, as Turkish Prime

Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan seized the opportunity to raise a new crop of corporate

loyalists. But Turkey was also benefiting from cheap but mobile portfolio

capital inflows during this period. With a population of more than 70 million

and a steadily growing economy, Turkey became heavily reliant on outside

investment to finance a hefty energy import bill, leading to chronic current

account deficits.

Average Monthly Foreign

Portfolio Investment:

Turkey's key vulnerability is that most of the foreign investment it

attracted was made into debt, and to a lesser extent equities, instead of

foreign direct investment into companies that both provide jobs and are more

difficult to liquidate in times of crisis. Total portfolio investment into

Turkey in the year ending in November 2013 equaled $26 billion, while foreign

direct investment was only $11 billion. Therefore, market skittishness has a

much higher potential to severely undermine Turkey's finances than in other

countries where foreign direct investment is the primary type of financial

inflows.

With Turkey's economic record tightly linked to the AKP's political

track record, it is little wonder that deeper political forces are now

realigning to challenge the AKP's clout and fracture Erdogan's patronage

network in this highly volatile election season. Turkey's venomous political

struggle will intensify in the coming months, blunting efforts by the Turkish

central bank to assuage investor fears.

Indonesia

Indonesia’s economic situation has changed rapidly in recent years.

Cheap capital inflows primarily into public sector debt facilitated a

significant boost in Indonesia’s imports. Rising demand for foreign goods

coupled with a fall in prices in commodity markets pushed Indonesia’s current

account balance into negative territory for the first time in 2012, and it has

worsened since then. (A recent decision to ban exports of some unprocessed

minerals will not help.) The currency fell by 20 percent in relation to the

dollar since the United States first began discussing withdrawing monetary

stimulus in mid-2013. The Indonesian central bank has responded by gradually

raising interest rates, but rates remain below inflation, which is at the

highest since the credit bubble in 2008, creating a situation of real negative

interest rates.

The government’s response is complicated by upcoming legislative

elections in April and presidential elections in July that will likely give

Indonesia a new ruling party for the first time in a decade. Indonesian voters

have already had to endure a fuel price hike in 2013 as the government sought

to trim its subsidy bill. A rapid increase in interest rates would have the

effect of slowing spending domestically and could hurt the country’s growth

prospects. With the prospects of a meaningful shift in the leadership ahead for

Indonesia, there is persistent concern over whether the country will be able to

convert economic uncertainty and a slowdown in growth into an opportunity for

reform.

India

India is gearing up for general elections expected in May. Current

polling shows the Bharatiya

Janata Party, India's main opposition party, leading ahead of the incumbent Indian National Congress. Domestic and foreign

observers expect a Bharatiya Janata-led government to

have a more investor-friendly, pro-business policy agenda. However, the

challenges facing India's new government will be extensive, including strong

institutional barriers for New Delhi to rapidly assert control over India's disparate

states.

The election comes as India anticipates growth to slip below 5 percent

in the coming year. India's current account is in chronic deficit. Marginal

gains were made in 2013, when the current account deficit was estimated to be

$78 billion. However, this slight improvement was driven in large part by

restrictions on gold imports that merely shifted the gold trade into the black

market, meaning that foreign currency continues to drain from the country at an

even more rapid rate than official statistics indicate. India has also seen a

downturn in portfolio investment from abroad, and the currency has depreciated

14 percent since the first whispers of a taper began -- something that could

worsen inflation on imported goods but that has already helped Indian textiles

to be more competitive on global markets.

However, India's real challenges are longer term. The country remains

very energy poor and burdened with serving a

population of 800 million people living in poverty. New Delhi is caught between

having to develop policies that not only facilitate the growth needs of a

vibrant metropolitan marketplace with deep ties to international markets but

also address the needs of an enormous, poor rural population requiring

consistent subsidization. The indelible contradiction and competition for

resources between the two economies of India will only exacerbate divisions

between local and national authorities, restricting New Delhi's options no

matter who is in power.

For updates click homepage

here