By Eric

Vandenbroeck

The Balfour

Declaration

A celebrated chronicler of pre-Zionist Palestine.

was Mark Twain, who wrote about his travels in the Holy Land in The Innocents

Abroad in 1869. That is three years after Mark Sykes was there for the

first time.

The desolate

land was also catching the attention of Christian politicians in

nineteenth-century Britain. They began expressing the idea that it would be in

the best interests of the Jews and the world if the Jews returned to Palestine

and reclaimed it as their homeland. In 1838, Lord Lindsay published the first

edition of his Letters on Egypt, Edom, and the Holy Land after traveling

through Palestine. He opined that “it is possible that, in the changes of the

Turkish empire, Palestine may again become a civilized country, under Greek or

Latin influences; that the Jewish race, so wonderfully preserved, may yet have

another stage of national existence opened to them; that they may once more

obtain possession of their native land, and invest it with interest greater

than it could have under any other circumstances.”

Anthony Ashley

Cooper, seventh earl of Shaftesbury, a member of Parliament and a devout

Christian, was of much the same mind. On July 24, 1838, he wrote that he was

“anxious about the hopes and destinies of the Jewish people:”

Everything seems

ripe for their return to Palestine; ‘the way of the kings of the East is

prepared.’ Could the five Powers of the West be induced to guarantee the

security of life and possessions to the Hebrew race, they would now flow back

in rapidly augmenting numbers. The inherent vitality of the "Hebrew

race" reasserts itself with incredible persistence; its genius, to tell

the truth, adapts itself more or less all over the world, nevertheless always

emerging with distinctive features and a gallant recovery of vigor. There is an

unbroken identity of Jewish ideas down to our times: but the great revival can

take place only in the Holy Land.

The Zionist idea

was not forgotten in nineteenth-century Britain. It would continue to be

considered at the highest levels of the British government, along with,

paradoxically, schemes that would challenge Zionism at its core.

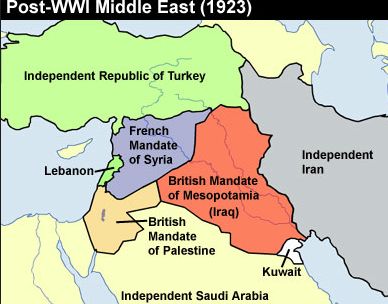

Then in the years that

followed its signing, the Sykes-Picot Agreement became the target of bitter

criticism. Lloyd George referred to it as an, ‘egregious’ and ‘foolish’

document; quite indignant that Palestine was ‘inconsiderately mutilated’ by the

‘carving knife of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which was a crude hacking of the

Holy Land’.1

As

we have seen before another consideration was that by 1914, Zionists of the

first and second Aliyot had increased Palestine’s Jewish community to a

critical mass of seventy-five thousand that gradually transformed it into a

modern economy. The First Aliyah (also The agriculture' Aliyah) is a term used

to describe a major wave of Zionist immigration to what is now Israel (Aliyah)

between 1882 and 1903. Jews who migrated to Ottoman Palestine in this wave came

mostly from Eastern Europe and from Yemen. An estimated 25,000–35,000Jews

immigrated to Ottoman Palestine during the First Aliyah. The second Aliyah that

took place between 1904 and 1914, during which approximately 35,000 Jews

immigrated into Ottoman-ruled Land of Israel, mostly from the Russian Empire,

some from Yemen.

Thus by 1914, 80,000-90,000 Jews – approximately 6 to 8 (other sources

cite up to 10 whereby a few only 6) per cent of the total population – lived in

Palestine without the assistance of any international state or sponsor. These

Jewish immigrants were legal migrants in the same way that 120,000 Jews legally

migrated from Eastern Europe to the UK between 1880-1914, and they lawfully and

openly bought land – much of it barren wasteland uncultivated by local Arab

farmers – from absentee land owners (virtually all of the Jezreel Valley was

purchased by Jews from only two people – the Turkish Sultan and a banker in

Syria).

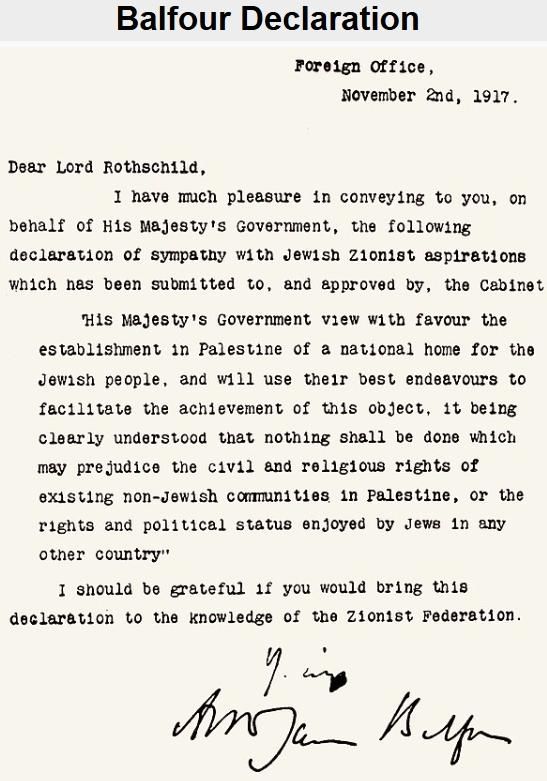

The Balfour declaration was approved, and communicated by Balfour to

Rothschild on 2 November 1917. The Egyptian authorities wanted to forestall the

international administration of the brown area laid down in the Sykes–Picot

agreement. The best way to do this was to proclaim martial law for as long as

military operations continued. The War Office concurred. An implication of this

policy, in which the Foreign Office acquiesced for the moment, was that the

Zionists should not be permitted to undertake in Palestine any activities in

pursuance of the Declaration.

Thus there was a curious blend of sentiment (the romantic notion of the

Jews returning to their ancient lands after 1,800 years of exile) and anti-

Antisemitism (world Jewry was a force that could vitally influence the outcome

of the war) whereby in the end the idea was to use President Wilson’s

recognition of the Balkan nations’ right to self-determination – namely,

freedom from Ottoman rule – in order to overcome his opposition to the

implementation of this same policy in the Middle East. Thus, by supporting

Zionist aspirations in Palestine, the Lloyd George Governement thus strove to compel Wilson to expand his

policy regarding the 'small nations' from the European regions of the Ottoman

Empire to its Asian territories.

On 23 October 1918, General Sir Edmund Allenby instructed his military

administrators in that time Palestine – Colonel Philpin de Piépape

(OET North), General Ali Riza Pasha El Rikabi (OET

East) and Major-General Sir Arthur Money (OET South) – that ‘as far as possible

the Turkish system of government will be continued and the existing machinery utilised’. He also reminded them that ‘the administration

is a military and provisional one and without prejudice to future settlement of

areas concerned’.¹ This meant that the iron wall of military routine against

which Chaim Weizmann had beaten his head during his

sojourn in Palestine remained firmly in place.²

On 9 October 1918, Weizmann had been received by Balfour, and obtained

assurance, so Ormsby Gore reported to the Foreign Office on 15 November, that

‘when questions affecting Palestine came before the Allied Powers for decision

the Zionists would be heard thereon’. Ormsby Gore also informed the Foreign

Office that ‘the breach between Zionists and the League of British Jews has

been healed,' and that the fruit of this collaboration would be a ‘memorandum

regarding the definite aspirations of Jews in regard to Palestine.' As he had

seen the draft, Ormsby Gore believed he could ‘say that the proposals are both

wise and practical, though doubtless there will be some difficulty on the

question of territorial boundaries’.³

Ormsby Gore referred to the Advisory Committee on Palestine, under the

chairmanship of Herbert Samuel, in which prominent Zionists and non-Zionists

participated, with Ormsby Gore acting as one of the committee’s consultants. He

handed in the undated memorandum on 19 November. Its main points addressed the

questions of the mandatory power, the boundaries of Palestine and the Jewish

national home. Great Britain should receive the mandate for Palestine. As to

the suggested boundaries see the memorandum stated that:

The boundaries of Palestine should be as follows:– In the North, the

northern and southern banks of the Litani River, as

far north as latitude 33°45˝. Thence in a south-easterly direction to a point

just south of the Damascus territory and close to and west of the Hedjaz

Railway. In the East, a line close to and west of the Hedjaz Railway. In the

South, a line from a point in the neighbourhood of

Akaba to El Arish. In the West, the Mediterranean Sea.

With respect to the national home, it was claimed that ‘Palestine should

be placed under such political, economic, and moral conditions, as will favor

the increase of the Jewish population, so that in accordance with the

principles of democracy it may ultimately develop into a Jewish Commonwealth.'

Ormsby Gore was no longer sure about the wisdom and the practicability

of the Committee’s proposals, at least those regarding the boundaries and the

national home. The first ‘should not be published,' and as far as the second

was concerned, ‘the word “Commonwealth” would be interpreted as “State” and

give rise to great un- easiness among the non-Jews of Palestine.' It was better

to omit the whole sentence. Sir Eyre Crowe concurred, and submitted that

Weizmann should be approached to make the necessary alterations, to which Lord

Hardinge added that these ‘should be accepted unconditionally.' Lord Robert

Cecil feared that, even in its amended form, it contained passages that would

‘raise great trouble with the Arabs. As Feisal is here, could not Dr Weizmann talk

it over with him?’⁴

Cecil’s fears were confirmed by three telegrams from Clayton. In the

first, he warned that the Palestinian Arabs were ‘strongly anti-Zionist and […]

very apprehensive of Zionist claims’, also because ‘local Zionists contemplate

a much more extended programme than is justified by

the terms of Mr Balfour’s declaration’.⁵ In the

second telegram, Clayton explained that ‘Christian and Moslem antipathy to

Zionism has been displayed much more openly since armistice the recent

Anglo–French decla ration has encouraged all parties

to make known their wishes by every available means in view of approaching

Peace Conference’. He accordingly considered the ‘present time […] particularly

unsuitable for special Zionist activity in Palestine which should be delayed

until status of country and form of administration has been finally decided

upon’.⁶ This equally applied, so Clayton ob- served

in the third telegram a few days later, to ‘any further declaration of Zionist

policy,' which ‘should be deferred until future of Palestine has been

definitely settled’.⁷

Weizmann had another interview with Balfour on 4 December. He stated

that the proposals of the Samuel Committee constituted ‘the necessary minimum of

the Zionist demands.' They did not contain ‘anything new,' and merely sketched

‘the broad lines of the measures which would have to be taken in order to carry

out in practice the policy laid down in the Declaration’. He also stressed once

again that the Jewish problem could only rationally and permanently be solved

through Zionism, but that this presupposed:

Free and unfettered development of the Jewish National Home in Palestine

– not mere facilities for colonisation, but

opportunities for carrying out colonising activities,

public works etc. on a large scale so that we should be able to settle in

Palestine about four to five million Jews within a generation, and so make

Palestine a Jewish country. Such development is possible if sufficient elbow

room is allowed to the Jewish people.

When Balfour ‘asked whether such a policy would be consistent with the

Statement made in his Declaration that the interests of non-Jewish communities

in Palestine must be safeguarded’, Weizmann replied that in ‘a Jewish

Commonwealth there would be many non-Jewish citizens, who would enjoy all the

rights and privileges of citizenship, but the preponderant influence would be

Jewish.

There is room in Palestine for a great Jewish community without

encroaching upon the rights of the Arabs.’ The foreign secretary agreed that

‘the Arab problem could not be regarded as a serious hindrance in the way of

the development of a Jewish National Home’, but like Cecil ‘thought that it

would be very helpful indeed if the Zionists and Feisal could act unitedly and

reach an agreement on certain points of possible conflict’.⁸

The Eastern Committee took up the question of Palestine the next day.

Curzon introduced the subject with an exposition of British commitments and the

existing state of affairs. One of the difficulties with which the British were

confronted was:

The fact that the Zionists have taken full advantage – and are disposed

to take even fuller advantage – of the opportunity which was then offered to

them […] their programme is expanding from day to

day. They now talk about a Jewish State. The Arab portion of the population is

well-nigh forgotten and is to be ignored. They not only claim the boundaries of

the old Palestine, but they claim to spread across the Jordan into the rich

countries lying to the east, and, indeed, there seems to be very small limit to

the aspirations they now form.

It was, therefore, no surprise that the ‘Zionist programme,

and the energy with which it is being carried out, have […] had the consequence

of arousing the keen suspicions of the Arabs […] who inhabit the country’. As

to the borders of Palestine, Curzon gladly availed himself of the opportunity

to point out that in the Sykes–Picot agreement ‘the most ridiculous and

unfortunate boundaries seem to have been drawn for that area.' It was

imperative that the British recovered ‘for Palestine, be it Hebrew or Arab, or

both, the boundaries up to the Litani on the coast,

and across to Banias, the old Dan, or Huleh in the interior.' With regard to

the eastern boundary proposed by the Zionists, which included ‘trans-Jordan

territories where there is good cultivation and great possibilities in the

future’, Curzon remarked that these had not been part of Palestine ‘for many

centuries, if [they] ever did’, while with respect to the Zionist claims on the

lands south of Beersheba, he noticed that there were ‘those who say:

“Do not complicate the Palestine question by bringing in the Bedouins of

the desert, whose face looks really to- wards Sinai, and who ought not to be

associated with Palestine at all”.

Curzon subsequently explained that an international or French

administration of the country was out of the question.

The choice was between the USA and Great Britain. Curzon plumped for Britain in

view of Palestine’s close economic ties with Egypt, its strategic importance

for the defense of the Suez Canal, and because ‘from all the evidence we have

so far, the Arabs and Zionists in Palestine want us. The evidence on that point

seems to be conclusive.’ Cecil agreed that the French were ‘entirely out of the

question […] also because the Italians would really burst if you suggested it –

and the Greeks too’, but he was not convinced that everything pointed to a

British mandate for Palestine. He did not wish ‘to rule out the Americans’, and

as far as Palestine’s strategic importance was concerned, he was ‘not much

impressed by the argument that in order to defend Egypt we had to go to

Palestine, because in order to defend Palestine we should have to go to Aleppo

or some such place. You always have to go forward; at least, I gather so.’⁹

On 16 December, the Eastern Committee adopted a resolution on Palestine

in which an international administration, as well as a French or Italian

mandate, was rejected. Great Britain should not object ‘to the selection of the

United States of America, yet if the offer were made to Great Britain, we ought

not to decline.' The choice between the two powers ‘should be, as far as

possible, in accordance with the expressed desires (a) of the Arab population,

(b) of the Zionist community in Palestine’. The British negotiators at the

peace conference were finally exhorted to make every effort ‘to secure an

equitable re-adjustment of the boundaries of Palestine, both on the north and

east and south’.¹⁰ The meeting between Faysal and Weizmann took place on 11

December 1918. It appeared that the basis for a mutual understanding was still

there. Both wanted to keep the French out of Syria and Palestine, and in return

for Zionist support of Faisal’s ambitions in Syria, the latter was prepared to

assist Zionist ambitions in Palestine. According to Weizmann’s report of the

meeting, Faisal had been ‘quite sure that he and his followers would be able to

explain to the Arabs that the advent of the Jews into Palestine was for the

good of the country, and that the legitimate interests of the Arabs would in no

way be interfered with’. When Weizmann had observed that ‘the country could be

so improved that it would have room for four or five million Jews, without

encroaching on the ownership rights of Arab peasantry,' the Emir had agreed. He

‘did not think for a moment that there was any scarcity of land in Palestine.

The population would always have enough, especially if the country were

developed.’¹¹

Small wonder, then, that on 17 December Weizmann wired to David Eder,

the acting chairman of the Zionist Commission, that his interview with Faisal

had been ‘most successful’. Weizmann also informed Eder that the Zionists had

formulated new proposals for the effectuation of the Balfour Declaration. The

most important were that ‘the whole administration of Palestine shall be so

formed as to make of Palestine a Jewish Commonwealth under British

trusteeship’, and that ‘Jews shall so participate in the administration as to

assure this object’. Clayton was greatly worried when he set eyes on this

telegram and wired the Foreign Office on 31 December 1918 that ‘in view of the

fact that quite 90% of the inhabitants of Palestine are non-Jewish, it would be

highly injudicious to impose, except gradually, an alien and unpopular element

which up to now has had no administrative experience’. Clayton’s telegram was

something of a surprise to the Foreign Office, as it had not received a copy of

Weizmann’s telegram to Eder. It was only on 9 January 1919 that, after

‘considerable difficulty’, it finally managed to get one. Both telegrams were

laid before Curzon on his first working day as acting secretary of state of

foreign affairs. He was ‘absolutely staggered’,¹² especially when read in

conjunction with Clayton’s earlier telegram of 5 December, in which he had

reported that ‘non-Jews in Palestine number approximately 573,000 as against

66,000 Jews’.¹³ Curzon ‘profoundly [pitied] the future Trustee of the “Jewish

Commonwealth” which at the present rate will shortly become an Empire with a

He- brew Emperor at Jerusalem’. He had, however, to admit that his ‘views on

this subject are unpopular’. He gave instructions that when sending the

telegrams to the peace delegation at Paris it should be ‘stated that I agree

with General Clayton and that I view the proposals of the Zionist Commission

which so far as I know have no sanction in any undertakings yet given by us,

with no small alarm’.¹⁴

A few days later, Curzon had an interview with General Money. In a

letter to Balfour he informed the latter that both Money and Allenby stressed

that ‘we should go slow about the Zionist aspirations and the Zionist State.

Otherwise we might jeopardise all that we have won. A

Jewish Government in any form would mean an Arab rising, and the nine-tenths of

the population who are not Jews would make short shrift with the Hebrews.’ He

added that he shared the generals’ view, and that he had ‘for long felt that the

pretensions of Weizmann and Company are extravagant and ought to be checked’.¹⁵

Balfour clearly had fewer qualms. He wrote back to Curzon that as far as he

knew ‘Weizmann has never put forward a claim for the Jewish Government of

Palestine. Such a claim is in my opinion certainly inadmissible and personally

I do not think we should go further than the original declaration which I made

to Lord Rothschild.’¹⁶

On 9 January, Clayton, who had been recalled to London for

consultations, telegraphed to Allenby that the Zionists had ‘come to definite

arrangement with Feisal with whom they are in close cooperation’.¹⁷ Faisal and

Weizmann had managed to reach an agreement on 3 January. Its main points were

as follows:

first, the boundary between Palestine and the Arab state should be

determined by a commission after the end of the peace conference; second, the

‘constitution and administration of Palestine’ should ‘afford the fullest

guarantees for carrying into effect’ the Balfour Declaration; and third: All necessary measures shall be taken to

encourage and stimulate immigration of Jews into Palestine on a large scale,

and as quickly as possible to settle Jewish immigrants upon the land through

closer settlement and intensive cultivation of the soil. In taking such

measures the Arab peasant and tenant farmers shall be protected in their

rights, and shall be assisted in forwarding their economic development.

Faisal, however, added the proviso that ‘if the Arabs are established as

I have asked in my manifesto of January 4th [actually dated 1 January 1919] […]

I will carry out what is written in this agreement. If changes are made, I

cannot be answerable for failing to carry out this agreement.’¹⁸ Arnold Toynbee minuted

that Lawrence had told him that ‘in the first draft of the present document, Dr

Weizmann used the phrases “Jewish State”, “Jewish government”, and that the

Emir Feisal altered these to “Palestine”, “Palestinian government”.’ Ormsby

Gore believed it was ‘a very important document and should be compared very

carefully with the new demands of the Zionist Organisation

contained in their memorandum for the peace conference’,¹⁹ which Nahum Sokolow

communicated to Sir Louis Mallet on 20 January.²⁰

Two days later, Ormsby Gore completed a note on the latest Zionist

proposals. These went:

Very much further than any demands hitherto put forward by responsible

Zionists. The phrase ‘Jewish Commonwealth’ has been introduced as the result of

a resolution passed by the American Jewish Congress of December 16th, 1918.

What exactly is meant by the world ‘Commonwealth’ is not defined, but it is

clear that it involves steps towards the creation of what is practically and

virtually if not nominally a Jewish government in Palestine.

He further stated that ‘the real character of these new proposals can be

most readily appreciated by attention to the section dealing with the

“Administration” of the future Palestine’. According to the Zionists, the

governor of Jerusalem ‘must be a man of the Jewish religion’, and could only be

appointed by the mandatory power after consulting ‘the Jewish Council for

Palestine, an extra Palestinian body representative of Jews in all countries’.

Ormsby Gore could ‘imagine few things which would create greater distrust of

Zionist aims among both Christian and Moslem inhabitants of Palestine than the

insistence upon a racial and religious test’ for the governor of Jerusalem. He

considered the ‘proposals regarding the Executive Council and the Legislative

Council […] even more extreme’. The Zionists proposed that ‘on both councils

there should be an assured Jewish majority. Thus racial and religious tests are

to be introduced and gross over-representation of the Jews in proportion to the

rest of the population is to be insisted upon.’ There were ‘many other smaller

points’ to which Ormsby Gore took exception, and in conclusion he observed

that:

In general it would seem that Dr

Weizmann who has hitherto been moderate and reasonable in his proposals has

been pushed along by the Jewish Jingoes of America and neutral countries who

having been given an inch want an ell. To my mind such extravagant demands will

injure and not assist the cause of Zionism both in Palestine and elsewhere and

if these demands are persisted in I presume H.M.G. will make it clear that they

cannot be answerable if they lead to disaster and reaction.

Sir Louis Mallet entirely agreed and suggested that Orms- by Gore should

be ‘authorised to communicate with Dr Weizmann and Mr Sokolov with a view to modifying this document.' Mallet

also mentioned the matter to Balfour, ‘who agreed that we should point out the

unwisdom of putting forward such proposals’, and discussed it with Sir Eric

Drummond, who ‘deprecated our making ourselves, in any way, responsible for

this case […] The less they mention Great Britain the better, except to say

that they desire our tutelage.’²¹ All these sentiments were reflected in the

letter Ormsby Gore sent to Sokolow on 24 January. He had spoken to Mallet and

Drummond and both ‘wished it to be made quite clear to you that there must be

no suggestion that your proposals have been approved by the British government.

There is no objection to you asking for Great Britain as Mandatory provided you

do this entirely on your own.’ He also stated that Mallet had ‘made it quite

clear that in his opinion the British government would not accept the duties of

a Mandatory if the constitution proposed in the printed Memorandum were

insisted upon by you and the Conference’, and that Sir Louis and he ‘certainly

both think this Memorandum is far too extreme as well as being much too long

and too detailed’. It would be better if the Zionists submitted ‘something

briefer and less likely to offend the susceptibilities of the majority of the

present inhabitants of Palestine’.²²

The next day, Kidston reported that Weizmann had come ‘to see me a

couple of days ago and said that he was seriously distressed about the position

in Palestine. The Jews were not receiving that consideration which they had

expected in a country which was to be their national home.’ In reply, Kidston

had pointed out that British ‘officers had many conflicting interests to

reconcile and the Jews were making their task difficult by their importunity.

They seemed to think that their national home must be handed over to them

ready-made at a moment’s notice.’ Graham thought ‘Mr

Kidston’s language perfectly correct’, and observed that Weizmann had never

‘publicly asked for more than a Jewish “national home” in Palestine – with the

idea of a Jewish commonwealth always looming in the background’. This induced

Curzon to have a second look at Weizmann’s telegram to Eder of 17 December, in

which the former had stated that Palestine should become ‘a Jewish Commonwealth

under British Trusteeship’. Curzon wondered:

Now what is a Commonwealth? I turn to my dictionaries and find it thus

defined:– ‘A State’, ‘A body politic,’ ‘An independent Community’. ‘A

Republic’. Also read the rest of the telegram. What then is the good of

shutting our eyes to the fact that this is what the Zionists are after, and

that the British Trustee- ship is a mere screen behind which to work for this

end?²³

Curzon decided to devote a further letter to Balfour to this question.

He entertained ‘no doubt that [Weizmann] is out for a Jewish government, if not

at the moment, then in the near future’. He pointed out that Weizmann, in his

account of his meeting with Balfour on 4 December, had:

Deliberately inserted the underlined words: ‘all necessary arrangements

for the establishment in Palestine of a Jewish National Home or Commonwealth.’

You meant the first, but he interpreted it as meaning the second. Again, on

December 17, he telegraphed to Eder of the Zionist Commission at Jaffa: ‘The

best proposal stipulates that the whole administration of Palestine shall be

formed as to make Palestine a Jewish Commonwealth.’

Curzon therefore felt ‘tolerably sure’ that Weizmann contemplated ‘a

Jewish state, a Jewish nation, a subordinate population of Arabs ruled by Jews,

the Jews in possession of the best of the land and directing the

Administration’, and that he was ‘trying to effect this behind the screen and

under the shelter of British trusteeship’. Curzon’s complaint made no

impression whatsoever in Paris. Balfour merely wanted to know when did he talk

‘about a Jewish Commonwealth?’, while Drummond minuted

that ‘this hardly requires an answer’.²⁴

Ormsby Gore’s letter to Sokolow proved to be far more effective. On 30

January, Mallet minuted that Samuel had called on him

‘to say that he had revised the Zionist case for the Conference and that the

demand for a Jewish Governor, a majority on the Council, had been eliminated

and the tone of the document greatly modified.' Samuel had also explained that

a ‘reference to the development of the country later on into a Jewish

Commonwealth’ had nevertheless been left in, ‘in deference to the views of

American Zionists who wanted something more to look forward to than a National

Home’.²⁵

The ‘Statement of the Zionist Organisation

Regarding Palestine’ was finally submitted to the peace conference on 3

February 1919. The Allied and Associated Powers were asked to ‘recognise the historic title of the Jew- ish people to Palestine and the right of the Jews to

reconstitute in Palestine their National Home’, to vest the country’s

sovereignty in the League of Nations, and to appoint Great Britain as the

mandatory power. The man- date should be: Subject also to the following special

conditions:– (I) Palestine shall be placed under such

political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the

establishment there of the Jewish National Home and ultimately render possible

the creation of an autonomous Commonwealth, it being clearly understood that

nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of

existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine or the rights and political status

enjoyed by Jews in any other country. (II)

To this end the Mandatory Power shall inter alia; (a) Promote Jewish

immigration and close settlement on the land, the established rights of the

present non Jewish population being equitably safeguarded. (b) Accept the

cooperation in such measures of a Council representative of the Jews of

Palestine and of the world that may be established for the development of the

Jewish National Home in Palestine.

The boundaries the Zionist Organisation

claimed for Palestine were the same as those indicated in the Advisory

Committee’s proposals communicated to the Foreign Office in the middle of

November.

Whereas Faisal’s statement had enthusiastically been received by members

of the British delegation at the peace conference, the one by the Zionist Organisation mainly drew critical comments, in particular

on the proposed boundaries and Council. Ormsby Gore minuted

that the ‘northern boundary is a little too far north, the Eastern boundary

proposed here […] too far East and I do not believe that Akaba can be usefully

developed as a part of Palestine’. He thought that a Jewish council might be

helpful ‘to prevent speculation and to facilitate the provisions of funds and

land for the development of the Jewish national home,' but it ‘should have no

political functions and the fewer administrative functions it has the better’.

Mallet wished to go even further. This ‘Jewish Council should […] be merely a

consultative body and have no powers of administration in Palestine. If it has,

little by little it will encroach and be- come very embarrassing for the

Governor. It should clearly not be in the Mandate conferred by the Peace

Conference.’ He also concurred that ‘Akaba should certainly not be included in

Palestine. We have agreed upon a boundary with the American delegation and I am

refer- ring it to the Egyptian experts.’²⁶

The British Military

Administration

Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen lunched with Balfour

on 7 February 1919. Afterwards he noted in his diary that he had bluntly asked

the foreign secretary whether the Declaration was ‘a reward or bribe to the

Jews for past services given in the hope of full support during the war?’

Balfour had immediately replied, ‘certainly not; both the Prime Minister and

myself have been influenced by a desire to give the Jews their rightful place

in the world; a great nation without a home is not right’. Meinertzhagen

had then asked whether, ‘at the back of your mind do you regard this

declaration a charter for ultimate Jewish sovereignty in Palestine or are you

trying to graft a Jewish population on to an Arab Palestine?’ This time Balfour

had not answered right away, and when he did, he had chosen ‘his words carefully

“My personal hope is that the Jews will make good in Palestine and eventually

found a Jewish State. It is up to them now; we have given them their great

opportunity”.’²⁷

The ambiguity inherent in the Balfour Declaration was also something

that troubled Cardinal Bourne, the archbishop of Westminster, who was visiting

Palestine at the time. On 25 January he wrote to Lord Edmund Talbot, the

conservative chief whip, that the declaration ‘was very vague and is

interpreted in many ways’. He related that ‘the Zionists here claim that the

Jews are to have the domination of the Holy Land under a British Protectorate;

in other words they are going to force their rule on an unwilling people of

whom they form only 10%’, and noted that ‘the officials are clearly at a loss

how to act for fear of giving offence and being disavowed at home if they

withstand Zionist pretensions’. The cardinal therefore begged Talbot ‘to urge

on the Prime Minister and Mr Balfour the immediate

need of a clear and definite declaration on the subject of Zionism’. Talbot had

passed on Bourne’s letter to the Prime Minister, who on 15 February wrote to

Kerr that ‘if the Zionists claim that the Jews are to have domination of the

Holy Land under a British Protectorate, then they are certainly putting their

claims too high’. He also informed Kerr that he had ‘heard from other sources

that the Arabs are very disturbed about the Zionists’ claims’. He warned that

‘we certainly must not have a combination of Catholics and Mohammedans against

us. It would be a bad start to our government of Palestine.’²⁸

In the discussion on how the Balfour Declaration should be interpreted –

did it mean that there would be a national home for the Jews in an

Arab-dominated Palestine, or that the home constituted the basis on which a

Jewish-dominated Palestine would be erected, but with the civil and religious

rights of the Arab minority secure? – Kerr and Balfour adhered to the second

interpretation. According to Kerr, ‘we have promised that Palestine should be

treated as the national home of the Jews and that if the Jews migrate there in

sufficient numbers they will eventually become the predominant power in the

country’. Lloyd George should not be fooled by appeals to self-determination,

because these meant that ‘as the Jews are now only one tenth of the population

they will never get a look in at all’. If the Declaration meant ‘anything at

all it means that the Jews of the rest of the world through some kind of

Zionist Council shall not only have the right to foster immigration and

undertake the public work necessary to enable the Jews to immigrate but that

they should have some recognised position in the

governmental machinery’, if not, then ‘local influences will be able to stop

Jewish immigration and the development of Palestine as a Jewish home’.²⁹

Balfour was even more explicit:

The weak point of our position of course is that in the case of

Palestine we deliberately and rightly de- cline to accept the principle of

self-determination. If the present inhabitants were consulted they would

unquestionably give an anti-Jewish verdict. Our justification for our policy is

that we regard Palestine as being absolutely exceptional; that we consider the

question of the Jews outside Palestine as one of world importance, and that we

conceive the Jews to have an historic claim to a home in their ancient land;

provided that home can be given them without either dispossessing, or

oppressing the present inhabitants.³⁰

The Zionists presented their case to the peace conference on 27 February

1919. Sokolow was the first to address the Council of Ten. He said that ‘the

solemn hour awaited during eighteen centuries by the Jewish people had, at

length, arrived. The Delegates had come to claim their historic rights to

Palestine, the land of Israel.’ It was true that there existed ‘happy groups of

Jews’ in the countries of Western Europe and in America, ‘but these were,

comparatively speaking, only small groups. The great majority of the Jewish

people did not live in those countries and the problem of the masses remained

to be solved.’ Weizmann spoke next. Where Sokolow had made an emotional appeal

to the members of the Council of Ten, Weizmann appealed to their self-interest.

The disaster that had befallen the six to seven million Jews in Russia implied

that ‘Jewish emigration […] would increase enormously, whilst at the same time

the power of absorption in the countries of Western Europe and of America would

considerably decrease’. The result would be that ‘the Jews would find

themselves knocking about the world, seeking a refuge and unable to find one.

The problem, therefore, was a very serious one, and no statesman could

contemplate it without feeling impelled to find an equitable solution.’

According to Weizmann, ‘the solution proposed by the Zionist organisation was the only one which would in the long run

bring peace, and at the same time transform Jewish energy into a constructive

force, instead of being dissipated into destructive tendencies or bitterness’.

It was also a realistic proposal, be- cause in Palestine ‘there was room for an

increase of at least 4,000,000 to 5,000,000 people, without encroaching on the

legitimate interests of the people already there. The Zionist wished to settle

Jews in the empty spaces of Palestine.’

American Secretary of State Robert Lansing asked Weizmann ‘to clear up

some confusion which existed in his mind as to the correct meaning of the words

“Jewish National Home.” Did that mean an autonomous Jewish government?’

Weizmann directly denied this, but when he continued it became clear

that this denial had to be qualified. In the short run the answer was ‘no’, but

in the long run it was ‘yes’. What the Zionists wanted for the moment was ‘an

administration, not necessarily Jewish, which would render it possible […] [to]

make Palestine as Jewish as America is American or England English’. Weizmann

ended by stating that ‘he spoke for 96 per cent of the Jews of the world, who

shared the views which he had endeavoured to express

that afternoon’.³¹ The next day, Clayton warned Curzon that in Palestine the

‘fear of Zionism among all classes of Christians and Moslems is now widespread,

and has been greatly intensified by publications in Zionist journals and

utterances of leading Zionists of a far reaching programme

greatly in advance of that foreshadowed by Doctor Weizmann’. Zionists

conveniently attributed ‘local anti-Zionist feeling to influence of “Effendis”

who are spoken of as corrupt and tyrannical’, but the truth was that ‘fear and

dislike of Zionism has become general throughout all classes’. Clayton also

observed that the increase in Zionist ambitions had resulted in a ‘lack of

confidence in Great Britain’, committed as Britain was to France and the

Zionists. In the eyes of the majority ‘America is the only power left’.³² He

returned to this theme in a dispatch he sent two days later. There was ‘little

doubt that in the early days of the occupation British protection or tutelage

would have been welcomed universally, and that fear and dislike of Zionism has

induced the present attitude in the population of Palestine’.³³

At the meeting of the Council of Four on 20 March, it was Clemenceau who

proposed that the inter-allied commission should

not limit its inquiries to Syria, but also visit Palestine, Mesopotamia and

Armenia. Lloyd George declared that he ‘had no objection to an inquiry into

Palestine and Mesopotamia, which were the regions in which the British Empire

were principally concerned’,³⁴ but Balfour was clearly worried. On 23 March, he

wrote a note in which he explained that he had spoken to Wilson and Lloyd

George on the inadvisability of including Palestine ‘in the sphere of

operations to be covered by the Com- missioners’. Both, however, had not

thought ‘the arguments [he] used were sufficiently strong to justify any

alteration in the draft already sanctioned’. He therefore wished ‘to put on

record my objections to the inclusion of Palestine within the area of

investigation’. The problem was that the commissioners were ‘directed to frame

their advice upon the wishes of the existing inhabitants of the countries they

are going to visit’. If they carried out these instructions, Balfour could

‘hardly doubt that their report will contain a statement to the effect that the

present inhabitants of Palestine, who in a large majority are Arab, do not

desire to see the administration of the country so conducted as to encourage

the relative increase of the Jewish population and influence’. This would have

the result that ‘the task of countries which, like England and America, are

anxious to promote Zionism will be greatly embarrassed’, and ‘the difficulties

of carrying out a Zionist policy […] much increased’.

At the Foreign Office, Clark Kerr considered Balfour’s fears ‘fully

justified’. It would ‘be interesting to see when Zionism will awake to the

danger of this threat against its aspirations’.³⁵ The Zionists as a matter of

fact had already done so. On 26 March, House noted in his diary that the

American Zionist Felix Frankfurter had been ‘an excited afternoon caller. The

Jews have it that the Inter-allied Commission which is to be sent to Syria is

about to cheat Jewry of Palestine.’³⁶ Hogarth wrote to Clayton four days later

that he had dined with Frankfurter and Weizmann, and ‘found both singing very

low’.³⁷ To Curzon, however, the possible outcome that the commission might find

against a British Mandate for Palestine provided the one glimmer of hope in connection

with the whole project. He wrote to Balfour on 25 March that he would ‘rejoice

at nothing more than that the Commission should advise that a mandate be

conferred upon anyone else rather than Great Britain’.³⁸

On 31 March, Balfour wrote to Samuel that he still had ‘great hopes that

Palestine will be eliminated from the scope of any Commission’, and added, for

Samuel’s ‘personal and confidential information’, that the dispatch of the

inter-allied commission was ‘still an open question and by no means definitely

determined’. However, Balfour’s main reason for writing his letter was that

‘the position in Palestine is giving me considerable anxiety.' He had received

reports ‘from unbiased sources that the Zionists there are behaving in a way

which is alienating the sympathies of all the other elements of the population.

The repercussion is felt here and the effect is a distinct set back to

Zionism.’ He therefore requested Samuel to warn ‘the Zionist leaders both here

and in Palestine that they would do well to avoid any appearance of unauthorised interference in the administration of the

country’.³⁹ Balfour sent a letter in the same vein to Weizmann three days

later.⁴⁰

Samuel replied on 7 April. He was very glad

to know that there still was ‘a prospect that the question of Palestine may be

settled without the long delay involved by a local inquiry by Commission’.

Regarding Balfour’s worries, he had ‘already spoken to one or two of the

Zionist leaders here in the sense of the latter part of your letter and am

sending a message to Dr Weizmann also’, but his sources had told him that there

was ‘another side to the case’. The Jews in Palestine felt ‘a sense of

grievance that the military administrators there usually proceed as though the

Declaration of November 1917 had never been made’. They were ‘unsympathetic

military men, from the Soudan and elsewhere, who have never heard of Zion- ism,

who regard all the inhabitants as “natives”, and who give preference to the

Arabs to the detriment of the Jews […] because they have been accustomed to

deal with similar people and understand them better’. Weizmann in his reply did

not mince words. They were ‘dealing […] with purposeful and organised

misunderstanding. Indisputably a vigorous agitation is on foot.’ He, too,

wished to direct Balfour’s ‘attention to the quality of British officials who

are in the administration in Palestine’, who ‘however well

intentioned […] bring to Palestine an out- look hardened by experience

in Egypt or the Sudan. All Zionists […] know your deep friendliness and that of

General Allenby to our cause […] unfortunately, as we proceed down the line of

military and civil officials the spirit is lost in transmission.’⁴¹ Weizmann

therefore thought that ‘it would be of very great value if an officer from here

who knows the East and is acquainted with the questions involved were to go

out’. He added that ‘the C.I.G.S. con- curs in this opinion’.⁴² Clayton,

however, certainly did not. According to him there was no necessity ‘to send an

Officer out from England’.⁴³

Clayton telegraphed a report by Money to the Foreign Office on 2 May

1919. Like Clayton, the latter claimed that ‘in the present state of political

feeling there is no doubt that if Zionist’s programme

is a necessary adjunct to a mandatory the people of Palestine will select in

preference the United States or France as the mandatory power’. The idea that

‘Great Britain is the main upholder of the Zionist programme

will preclude any local request for a British mandate’. Money therefore

submitted that ‘if a clear and unbiased expression of wishes is required and if

a mandate for Great Britain is desired by His Majesty’s Government it will be

necessary to make an authoritative announcement that the Zionist programme will not be enforced in opposition to the wishes

of majority.' Clayton added that he concurred in Money’s appreciation of the

situation. According to him, ‘fear and distrust of Zionist aims grow daily and

no amount of persuasion or propaganda will dispel it […] A British mandate for

Palestine on the line of the Zionist programme will

mean the indefinite retention in the country of a military force considerably

greater than that now in Palestine.’

Kidston believed that Clayton’s views were ‘particularly sound’, but

rather doubted whether these were ‘shared by the War Office here, for Colonel

Gribbon rang me up yesterday on the telephone with the express object of saying

that he thought that too much attention should not be paid to this opinion on

the situation’. When Kidston had subsequently aired Curzon’s point of view that

‘it might be a blessing if the mandate were to go elsewhere’, Gribbon had been

‘profoundly shocked and maintained that Palestine was essential to us

strategically for the defence of Egypt’.⁴⁴ In Paris,

General Thwaites informed Hardinge that Allenby agreed with Money’s assessment

that ‘if Great Britain desires the people to vote for a British mandate it will

be necessary to make an authoritative announcement that the Zionist programme will not be enforced in opposition to the wishes

of the majority’. However, in sharp contrast to the way in which the military

authorities in London and Paris handled the Syrian dossier, Thwaites proposed

not to defer to the military authorities on the spot. If the British government

persisted in their policy of backing ‘a moderate Zionist policy’, it would

moreover ‘be worthwhile to bring new blood into General Allenby’s political

administration by sending out an officer, such as Colonel Meinertzhagen,

who, with full knowledge of the position in Europe could help General Allenby

to overcome the difficulties’ he was confronted with. Forbes Adam minuted that Weizmann had told him that a proclamation as advocated

by Money, Clayton and Allenby would ‘produce a violent disturbance in Eastern

Europe the effects of which might be much more disastrous and far reaching than

the opposition of the local population (Christian and Moslem) of Palestine to

the decisions of the Conference’. Mallet merely observed ‘we cannot possibly go

back’.⁴⁵

During a meeting of the Samuel Committee on 10 May, Weizmann admitted

that lately ‘a great deal’ had been heard ‘about the unrest amongst Arabs and

their opposition to Zionism’, but mainly blamed this on a lack of support of

the Zionist movement ‘by the Administration on the spot’, in particular ‘the

lower officials who in some cases have done a great deal of irreparable

damage’. The military authorities had apparently lost confidence in ‘the

possibility or advisability of putting into effect the Balfour Declaration’,

but nothing could be ‘more unjust and short-sighted than that. Jewry is not

going to give up its claim to Palestine and Great Britain or America is not

going back on a solemnly pledged word.’⁴⁶ This was precisely the line Balfour

took in a letter to Curzon on the declaration proposed by Money. There could

‘of course be no question of making any such announcement as that suggested […]

and in this connection it might be well’ to remind Clayton that ‘the French,

United States and Italian governments have approved the policy set forth in my

letter to Lord Rothschild of November 2nd, 1917’. Balfour also informed Curzon

that Thwaites had suggested that ‘it might be advisable at this stage to send

out to Palestine a further advisor on Zionist matters to assist General

Clayton’, and that Thwaites had ‘pro- posed, in this connection, Colonel Meinertzhagen, D.S.O. as the most suitable person’.⁴⁷ The

Foreign Office telegraphed Balfour’s observations to Clayton without further

comment on 27 May 1919.⁴⁸ Clayton replied on 9 June: ‘your remarks noted. With

regard to Colonel Meinertzhagen if you send him out

he will be useful to me.’⁴⁹ From a later telegram it appeared that he was not a

bit impressed by Balfour’s reminder that Britain’s allies also supported the

Zionist cause. He wired on 19 June that ‘unity of opinion among the Allied governments

on the subject of Palestine’, was ‘not a factor which tends to alleviate the

dislike of non-Jewish Palestinians to the Zionist Policy. Indeed, it rather

leads to still further anxiety on their part to express clearly to the world

their own point of view.’⁵⁰

In a minute of 3 June, written in a letter that the secretary of the

Zionist Commission had sent to Aaron Aaronsohn and

Felix Frankfurter at the beginning of May, Meinertzhagen

left little doubt as to the side he was on in the struggle between Zionists,

Arabs, and the British military authorities. The secretary had violently

complained about the Palestinian Arabs, who were ‘the most cowardly and

weak-kneed Moslems’, the native Christians, who had joined the anti-Jewish

movement ‘stimulated by an endless flow of French gold’, and the military

administration, who it seemed had ‘received the mot d’ordre to put the Jew at a disadvantage. With each

Governor or sub-Governor there is an Arab or Christian advisor, who influences

the British official against the Jews.’ The regrettable truth was that Great

Britain had ‘lost all power and prestige here […] Only fair and strong action

can save Great Britain’s position with the Moslems.’ Meinertzhagen

commented that he knew ‘the writer of this letter. He is a moderate, level-headed,

and sensible Zionist’. The letter further only confirmed ‘which we already know

namely that our administration in Palestine is in a unhappy state and has been

signally unsuccessful in getting the sympathy of the Jew and the confidence of

the Arab’.⁵¹

On 31 May, Sir William Tyrrell communicated a part of Clayton’s telegram

of 2 May to Samuel, and explained that Balfour had suggested that Samuel

‘should be consulted […] with a view to ascertaining whether you have any

proposals to offer as to how the present hostility to Zionism in Palestine can

best be allayed by the administrative authorities on the spot’.⁵² In his reply,

Samuel presented a complete catalogue of the measures that according to the

Zionists should be taken to put an end to the unrest in Palestine. The first

was that ‘H.M. Government should send definite instructions to the local

administration to the effect that their policy contemplates the concession to

Great Britain of the Mandate for Palestine’, and that ‘the terms of the Mandate

will certainly embody the substance of the declaration of November 2nd 1917’.

The second was that the Arabs should be assured that ‘in no circumstances will

[they] be despoiled of their land or required to leave the country’, and that

there would ‘be no question of the majority being subjected to the minority’.

At the same time they should be reminded that a choice in favore

of America or France as the mandatory power for Palestine would bring no

solace, since ‘the American and French governments are also pledged to favour the establishment in Palestine of the Jewish

National Home’. The third measure was that the local authorities should ‘be

instructed to bring these facts to the attention of the Arab leaders at any

convenient opportunity, and to impress upon them that the matter is a chose jugée [the matter is final and not open to appeal] and that

continued agitation could only be to the detriment of the country and would

certainly be without result’. Samuel finally suggested that:

An officer, whether civil or military, who has been in close touch with

the British Delegation in Paris or with the Foreign Office in London, who is

well acquainted with the policy of H.M. Government in relation to Palestine and

is personally in sympathy with it, should be sent to Palestine with the special

mission of conveying to the local administration, more fully than can be done

by correspondence the views of the government.

Maurice Peterson at the Foreign Office minuted

on Samuel’s letter that ‘something like what Mr

Samuel proposes will, I fancy, have to be done after we have received the

mandate. But until then, and with the American Commission on its way, I doubt

if Paris will be ready for so bellicose a statement.’ Kidston related that he

had spoken with Samuel Landman of the Zionist Organisation,

who had complained that ‘either the attitude of H.M.G. towards Zionism had

changed or that the Military Administration in Palestine were not acting in

accordance with the policy of the Home Government’. Kidston had firmly taken

the side of the military administration, and warned Landman that the Zionists:

Must not forget that Palestine was still enemy occupied territory under

military occupation; they, like many were too apt to forget that we were still

in a state of war with Turkey; they expected the administration to act as if

peace had been signed and the mandate of Palestine already given to Great

Britain, we here were called upon to exercise a good deal of patience in these

days and I feared that the Zionists must learn to do the same.

Graham believed that ‘Mr Kidston’s reply met

the case very well’, and Curzon agreed, ‘the Zionists have only themselves to

thank’.⁵³ But where London sided with the military authorities, Paris sided

with the Zionists. Forbes Adam hoped that Samuel’s proposals would ‘be followed

up’,⁵⁴ and when on 24 June Balfour had a conversation with Louis Brandeis on

the eve of the latter’s visit to Palestine, he ‘expressed entire agreement’

with Brandeis’s understanding that ‘the commitment of the Balfour Declaration’

entailed that ‘Palestine should be the Jewish homeland and not merely […] a

Jewish homeland in Palestine’. Two days later, in the memorandum for Lloyd

George in which Balfour expressed the hope that the outlines of the Turkish

settlement should be agreed to by the Prime Minister and President Wilson left

Paris, it became clear that he also fully agreed with the two other conditions

that according to Brandeis must be fulfilled to enable the successful

realization of the Zionist program. The first was that there ‘must be economic

elbow room for a Jewish Palestine’, which ‘meant adequate boundaries, not

merely a small garden within Palestine’, and the second that ‘the future Jewish

Palestine must have control of the land and the natural resources which are at the

heart of a sound economic life’.⁵⁵ Balfour observed that Palestine’s northern

frontier ‘should give [the country] a full command of the water power which

geographically belongs to Palestine and not to Syria; while the Eastern

frontier should be so drawn as to give the widest scope to agricultural

development on the left bank of the Jordan, consistent with leaving the Hedjaz

railway completely in Arab possession’.⁵⁶ On 1 July, Balfour further stated in

a dispatch to Curzon that instructions should be sent to Allenby on the lines

of the measures Samuel had proposed in his letter. He also again brought up the

question of ‘the despatch of a further officer to

Palestine’, which ‘might in the first instance be discussed with General

Clayton on his forthcoming visit to England on leave’.⁵⁷

At the Foreign Office, a telegram was drafted containing Samuel’s

suggestions, but this was held up in order to obtain Clayton’s views upon it.

In the meantime, Samuel and Weizmann continued their attacks on the British

military authorities in Palestine. Sir Ronald Gra- ham recorded that he had an

interview with each on 2 July. Samuel had ‘complained of the attitude of the

British Military authorities […] and declared that they took every opportunity

of injuring Zionist interests’. He ‘earnestly’ hoped that ‘in the forthcoming

changes which were to be made in the administration of Palestine new officers

would be appointed who would possess a better understanding of the intentions

of His Majesty’s Government’. Weizmann had ‘referred in far more violent terms

to the present situation in Palestine. He declared that the British Authorities

were showing a marked hostility to the Jews and lost no opportunity of not only

injuring their interests but of humiliating them.’ Weizmann therefore

‘earnestly begged that the question should be taken in hand and that a new

spirit should animate the direction of affairs in Palestine’. Curzon, however,

refused to move: ‘to a large extent the Zionists are reaping the harvest which

they themselves sowed’.⁵⁸ After his arrival in London, Clayton had two meetings

with the Zionist leadership on 8 and 9 July. From his reports of the meetings

to the Foreign Office it appeared that he had not wavered under the barrage of

Zionist complaints and had stubbornly defended the line of policy adopted by

the military authorities. During the first meeting it had become clear that the

criticisms ‘brought up by Mr Samuel and Dr Weizmann

in their interviews with Sir R. Graham’ could not be ‘illustrated by specific

instances, except in the case of one or two incidents of minor importance’. He

had:

Pointed out that the present administration was a temporary and

provisional [one] and was not there- fore justified in pushing a Zionist policy

at a time when the future status of Palestine had not been decided by the Peace

Conference. However confident the Zionists might be that the eventual decision

would be in their favour, it would be incorrect for

the occupying power to prejudice that decision by acting as though the mandate

had already be given to Great Britain.⁵⁹

At the second meeting, Clayton had admitted that ‘individual

administrators may have appeared to show lack of will’, and attributed this ‘to

the fact that the staff of administrators was collected under great

difficulties, and from the material available at the time. Most of the best men

were already serving elsewhere.’ He had, however, insisted that the military

administration was ‘not placed there in order to carry out any particular

policy, but to maintain security in the country. They were in the position of a

trustee awaiting a decision regarding the fate of the country,’ and that this

implied, ‘in the absence of definite instructions from the Home Government’,

that the administration was ‘not justified in doing anything which could be

construed as in some way forestalling the mandate’.⁶⁰ It took more than a

fortnight after his meetings with the Zionists before the Foreign Office was

able to consult Clayton on the draft telegram to his deputy Colonel French

containing the instructions based on Samuel’s letter of 5 June. According to

this draft: His Majesty’s Government’s

policy contemplates concession to Great Britain of Mandate for Palestine. Terms

of Mandate will embody substance of declaration of November 2, 1917. Arabs will

not be de- spoiled of their land nor required to leave the country. There is no

question of majority being subjected to the rule of minority, nor does Zionist programme contemplate this. American and French governments

are equally pledged to support establishment in Palestine of Jewish national

home. This should be emphasised to Arab leaders at

every opportunity and it should be impressed on them that the matter is a

‘chose jugée’ and continued agitation would be

useless and detrimental. When Clayton

set eyes on the draft telegram on 25 July, it had been decided that Meinertzhagen would succeed him as chief political officer

for Syria and Palestine. He no longer put up a fight. He merely observed that

he agreed that ‘if the question is a “chose jugée”,

the sooner General Allenby is given a definite line the better’. However,

Curzon was not yet ready to give in. He was afraid that he could not ‘see why a

policy should be suggested or dictated to us by Mr

Herbert Samuel who is not a member of H.M.G.’ Neither did he ‘see why we should

lay down – in anticipation of the decision of the Peace Conference – (a) that

we are going to receive the man- date (b) what its terms are to be’. But this

was no more than a token resistance, because he added that this might be ‘the

policy of H.M.G. and if Mr Balfour so decides I have

nothing more to say’. On 4 August, Kidston could accordingly note that Curzon

had seen the draft telegram to French and ‘agreed to its despatch

as it apparently represents Mr Balfour’s policy’.⁶¹

On 23 July 1919, Weizmann wrote to Balfour on the impending resignations

by General Clayton and General Money.⁶² It was ‘essential’ that ‘these two very

important offices should be filled by men who are in complete sympathy […] with

the policy that His Majesty’s Government has adopted’. Replacing the chief

political officer and the chief military administrator was in Weizmann’s eyes

not enough. He expected that steps would be taken ‘to re- place officers, some

of them filling positions inferior only to those already mentioned, who,

according to all the information we have received, have shown themselves not

only unsympathetic but even hostile to the Jewish population of the country’.

When he transmitted the letter to the Foreign Office, Balfour confined himself

to the observation, on the suggestion of Forbes Adam, that he trusted that

Curzon and the War Office would ‘endeavour to meet Dr

Weizmann’s wishes in the matter of new appointments’.⁶³

Although nobody in Paris apparently took exception to Weizmann’s

interfering in the appointment of British officials, Clark Kerr in London

certainly did. He could not ‘help feeling that this is allowing the Jews to

have things too much their own way’, but supposed ‘we must bow to the ruling of

Paris’. He also related that Landman had told him that ‘a General Watson

[Major-General Harry D. Watson] was to succeed General Money’. Curzon initially

merely minuted that he wished ‘the letter had been

addressed to me’,⁶⁴ but subsequently decided to address one more letter to

Balfour to give vent to his indignation. He informed the latter ‘how much

startled’ he was:

At a letter from Dr Weizmann to you dated July 23 in which that astute

but aspiring person claims to ad- dress me as to the principal

politico-military appointments to be made in Palestine and to criticise sharply the conduct of any such officers who do

not fall on the neck of the Zionists (a most unattractive resting place) and

[…] the ‘type of man’ whom we might or might not to send.

It seemed that Weizmann would ‘be a scourge on the back of the unlucky

mandatory, and I often wish you would drop a few globules of cold water on his

heated and extravagant pretensions!’⁶⁵

When Curzon’s latest complaint arrived in Paris, Balfour was putting the

finishing touches to his long memorandum on the Syrian question. From his

observations on Palestine it appeared that Curzon’s appeals and Clayton’s

warnings had failed to make any impression. Balfour took the same position he

had taken in his letter to Lloyd George in the middle of February in reaction

to Cardinal Bourne’s letter, and in his note of the end of March, prompted by

the Council of Four’s decision to send an inter-allied commission of inquiry to

the Middle East. Balfour observed that:

In Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting

the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country, though the American

Commission has been going through the form of asking what they are. The four

Great Powers are committed to Zionism. And Zionism, be it right or wrong, good

or bad, is rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs, in future hopes, of

far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who

now inhabit that ancient land.

In my opinion that is right. What I have never been able to understand

is how it can be harmonised with the declaration, the

Covenant, or the instructions to the Commission of Enquiry. I do not think that

Zionism will hurt the Arabs; but they will never say they want it […] Whatever

deference should be paid to the views of those who live there, the Powers in

their selection of a mandatory do not propose, as I understand the matter, to

consult them.

With respect to Palestine’s borders, Balfour repeated what he had stated

in his memorandum to Lloyd George of 26 June. It was ‘eminently desirable’ that

Palestine ‘should obtain the command of the water-power which naturally belongs

to it, whether by extending its borders to the north, or by treaty with the

mandatory of Syria’, and ‘should extend into the lands lying east of the

Jordan. It should not, however, be allowed to include the Hedjaz railway.’⁶⁶

When General Watson filed his first report as military administrator on

16 August, he explained that ‘on taking over the Administration of O.E.T.A.

South I had an open mind with regard to the Zionist movement and was fully in

sympathy with the aim of the Jews for a National Home in Palestine – and with

that aim I am still in sympathy’, but that there was no escaping the fact that

‘the feeling of the great mass of the population is very antagonistic to the

scheme’. Opposition until now had been more inspired by nationalist than

religious sentiments, but he greatly feared that it might ‘take a religious

turn’ and lead to ‘a Holy War’. He emphasised, like

Clayton and Money had done before him, that the ‘antagonism to Zionism of the

majority of the population is deep rooted – it is fast leading to hatred of the

British – and will result, if the Zionist programme

is forced upon them, in an outbreak of a very serious character necessitating

the employment of a much larger number of troops that at present located in the

country’. He therefore urged ‘most strongly’, ‘for the sake of Zionism, for the

sake of the National Home for the Jews […] that the work of the establishment

of the Jews in Palestine be done very very slowly and

carefully. Peaceful penetration over a long period of years will bring about

the desired result.’⁶⁷

The Draft Declaration on

Zionism and the Borders of Palestine

In his long letter to Balfour of 20 August 1919, Curzon also devoted a

few lines to Palestine. The War Cabinet was divided on the question. Curzon was

very much in favor of withdrawing from the country ‘while yet we can’. Others

had, however, taken Balfour’s position that, ‘irksome as will be the burden’,

Britain could not ‘now refuse [the mandate] without incensing the Zionist

world’. Lloyd George for his part had clung to ‘Palestine for its sentimental

and traditional value, and [talked] about Jerusalem with almost the same

enthusiasm as about his native hills’.⁶⁸

During the first of his series of meetings with Field- Marshal Allenby

at Hennequeville, Lloyd George stated that it ‘was

essential to acquire the whole of Palestine without any truncation whatever’.⁶⁹

At their second meeting the next day, the Prime Minister wanted to know

‘whether it was proposed to include Mount Hermon within the boundaries of

Palestine’, as the Zionists claimed, but to him this seemed ‘to be rather

excessive’. Allenby concurred and assured Lloyd George that the line he ‘would

like to draw for Palestine […] would exclude Mount Hermon’. Because the French

insisted on the border agreed in the Sykes–Picot agreement, which meant that

Lake Tiberias would not form part of Palestine, Han- key was instructed to get

from London a copy of ‘Adam Smith’s Atlas (containing the boundaries of

Palestine at different periods)’ (a reference to George Adam Smith, Atlas of

the Historical Geography of the Holy Land, which had been published in 1915),

because Lloyd George ‘wanted a map showing what actually constituted Pales-

tine. He was convinced that this would include Lake Tiberias.’ Bonar Law

subsequently suggested that ‘President Wilson should be asked to arbitrate as

to the boundaries of Palestine’. He also wished to know ‘what was the value of

Palestine?’ Allenby replied that ‘it had no economic value whatsoever. Its

retention by the British would keep our minds active for the next generation or

two. He anticipated great trouble from the Zionists.’ Lloyd George could not

let this pass. He ‘pointed out that the mandate over Palestine would give us

great prestige’, but in Allenby’s view it was the other way around, ‘we could

[not] now give up Palestine without great loss of prestige’. Lloyd George cut

off this dispute by pro- claiming that ‘anyhow it was impossible for us to give

up Palestine’, and summed up the British position as ‘we could neither give up

Palestine nor take Syria’, to which Allenby agreed.⁷⁰

At their next meeting on 11 September, the Prime Minister started with

accepting Bonar Law’s plan of ‘leaving the arbitration of the northern boundary

of Palestine to someone selected by President Wilson’. Hankey subsequently

‘produced Adam Smith’s Atlas […] and some time was spent in examining [it]’.

Lloyd George concluded that ‘the maps of different epochs gave Haifa to

Palestine, but not Acre’, but Gribbon pointed out that this time the

Sykes–Picot line worked in Britain’s favour, as it

‘gave Acre to Palestine’. When the discussion shifted to the border between

Syria and Mesopotamia, Gribbon strongly advocated the inclusion of Deir es Zor

in the British zone, but Bonar Law was not impressed, ‘the French would make

out that the English grabbed every- thing good and left only what was useless’.

Allenby, too, was prepared to leave the town to the French, but first Britain

should claim it ‘as a bargaining asset […] in order to obtain a good line to

the north of Palestine’.⁷¹

With regard to the question of the frontiers between Palestine, Syria

and Mesopotamia, it was finally decided ‘after a prolonged conversation at the

dinner table’ in which Frank Polk, the head of the American delegation also

took part, that paragraph seven of the aide-mémoire to be presented at the

meeting of the Heads of Delegtions on 15 September

should merely state that ‘in the event of disagreement, the British government

was prepared to accept American arbitration in regard to the boundaries of

Palestine and Mesopotamia’.⁷²

Balfour had left Paris before Lloyd George arrived there. On his way to

Scotland for an extended holiday, he made a stopover in London on 10 September

and informed Curzon of his plans to resign as secretary of state for foreign

affairs. Curzon wrote afterward to his wife that he had gone ‘over everything

with him. He is never coming back to the Foreign Office in any capacity.’

Balfour had told him that ‘he would have resigned at once had not Lloyd George

pressed him to stay. He realises that this half-and-half

arrangement is hard on me; but says that he is not going to interfere in the

smallest degree.’⁷³ On 23 October, after Balfour had returned to London, Curzon

was finally appointed foreign secretary.

Colonel Meinertzhagen sent his first dispatch

to the Foreign Office on 26 September. He started, ‘as the value of any opinion

on controversial matter is enhanced by a knowledge of the personal leanings of

the informant’, with an exposition of his own position towards Zionism. He

explained that his ‘inclinations towards Jews in general is governed by an anti-semitic instinct which is in- variably modified by

personal contact. My views on Zionism are those of an ardent Zionist.’ He

therefore did not ‘approach Zionism in Palestine with an open mind, but as one

strongly prejudiced in its favour’. Meinertzhagen continued with an analysis of the situation

in Palestine. The existing opposition to Zionism sprang ‘from many sources, but

they are mainly traceable to a deliberate misunderstanding of the Jew and

everything Jewish – this in turn is based on contact with the local Jew, the

least representative of Jewry or Zionism’. It was accordingly not ‘difficult to

understand that in Palestine every man’s hand is against Zionism’, and that ‘to

reconcile this mass of opposition to the policy of H.M.G. has been no easy task

for our administration’, especially considering that the personal views of the

British administrators, ‘no matter how anxious they are to conceal them,

incline towards the exclusion of Zionism in Palestine’. On the whole however,

so Meinertzhagen believed, ‘our administration has

exhibited laudable tolerance towards a subject they dislike and towards a

community which is often unreasonable and by nature exacting’.

Ardent Zionist or not, his first weeks in Palestine had taught Meinertzhagen that the Zionist programme

could only succeed – and here he sounded very much like Clayton, Money and

Watson – if its ‘growth is slow and methodical. In its incipient stages Zionism

can only be artificial and unpopular and though it is realised

that eventual success must depend on its own merits, it is only by careful

nursing that it will develop a healthy growth.’ He had also reached the

conclusion, again in line with the previous warnings by Clayton, Money and

Watson, that ‘the people of Palestine are not at present in a fit state to be

told openly that the establishment of Zionism is the policy to which H.M.G.,

America and France are committed’. It had therefore ‘been found advisable to