By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

While a Brexit vote is very much possible, the leading voting reason is

for Britain to quit the EU in order to curb immigration. But not only would

there be the grave economic implications when the UK leaves, the Brexit

campaign and the rise of Europe's populist right have also dented Turkish hopes

of ever joining the EU, which in turn might worsen the migrant crisis in

Europe.

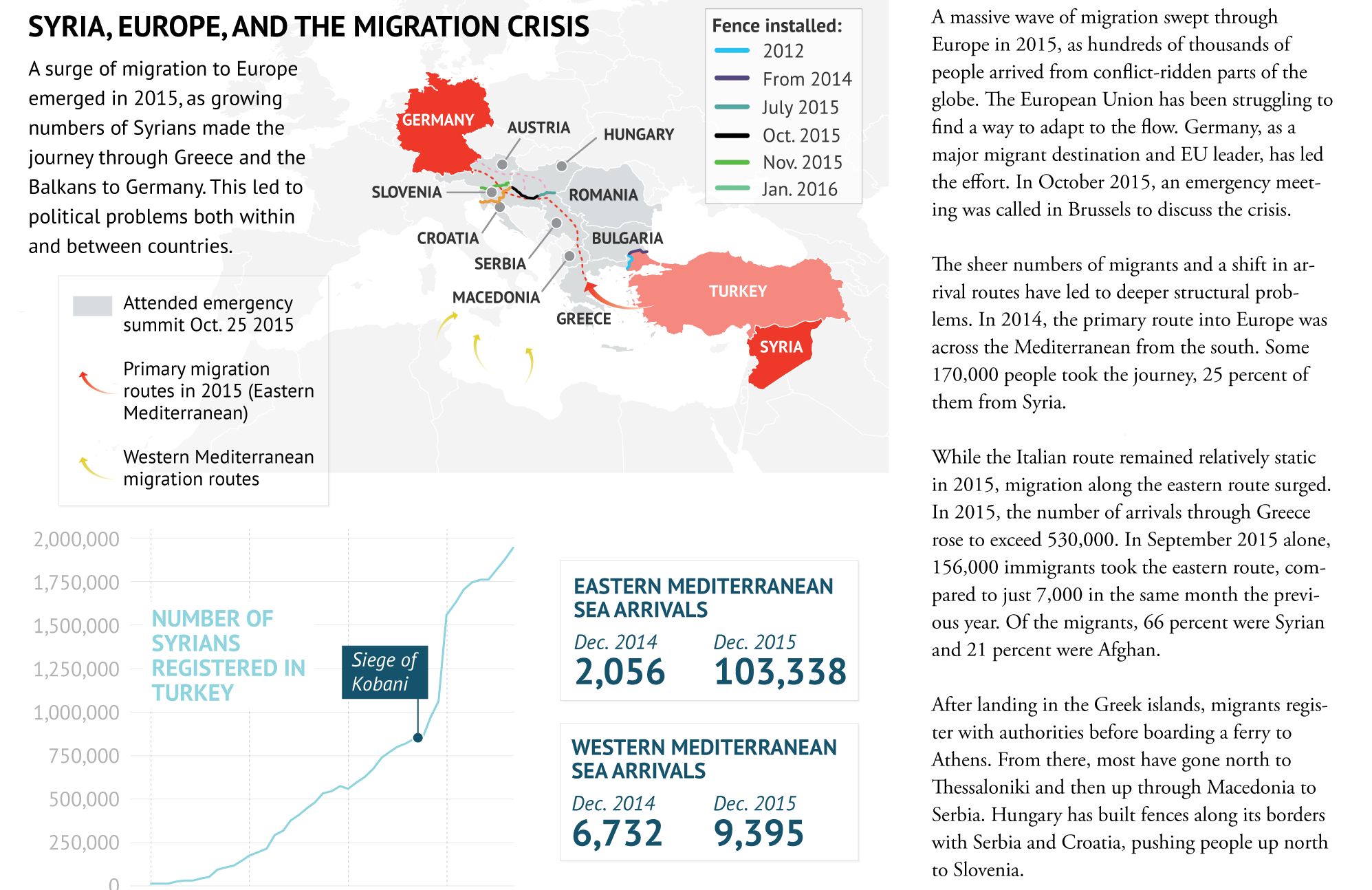

As conflict throughout the Middle East and North Africa continues

unabated, the influx of migrants from the war-torn region is putting more and

more strain on Europe. Hoping to lighten its load, the European Union turned to

Turkey for help. But a tentative deal struck between the two on March 18, now

threatens to start unraveling while putting also more pressure on a Brexit.

As the warm summer months approach, threatening to bring more migrants

to Europe's doorstep in droves, the Continent will have little choice but to

bend on some of its demands to cement the deal with Turkey.

Without Turkey's help, the European Union has few tools it can use to

stem the tide of migrants. In theory, it could turn migrants away at its

borders, but doing so would exacerbate the humanitarian crises driving them to

Europe in the first place, a consequence few EU countries are willing to

accept. Alternatively, the Continent could send migrants back to their homes.

But Brussels can negotiate repatriation agreements only with countries that are

considered safe. Because most of the migrants entering Europe are fleeing

conflict zones in Syria and Iraq, they are not candidates for repatriation.

That leaves Europe with only one option: to send migrants to a different

country. But few countries are eager to take on the costs of hosting Europe's

migrants. States along the Balkan route, for example, are determined to avoid

becoming transit territories for migrants, as they have been in the past. At

the same time, many Eastern European states remain strongly opposed to the

creation of a mechanism to distribute asylum seekers across the Continent.

As the conflict drags on just south of Turkey, the number of Syrian

migrants is bound to rise. The costs will grow accordingly, especially since

Syrians often end up in southern Turkish provinces, where unemployment is

already high. Many Turkish citizens living in these areas have similar

educational profiles to the migrants fleeing Syria, increasing the likelihood

of competition for low-skill jobs in sectors such as manufacturing and

construction. Because few Syrians have been able to obtain work permits, area

companies may be more inclined to hire them over their Turkish peers, whom

businesses would have to pay at least the minimum wage. The struggle to gain

employment could, in turn, lead to social tension and unrest. Meanwhile, half

of Syrian migrants are children, three-quarters of whom do not attend school, a

factor that could compound the socio-economic problems among Turkey's migrant

population in the future.

To determine the long-term success of the Turkey-EU deal, two questions

need to be answered: Will the European Union finalize the agreement, and if it

does, will that agreement be sustainable?

The answer to the first question is clear. The migrant deal is vital to

the Continent, which has few avenues for addressing the crisis on its own.

Therefore, the European Union will give Turkey the time it needs to meet the

bloc's requirements, and it will compromise on more sensitive issues, such as

counter terrorism laws, to keep Ankara on board. Because Brussels will have to

make its decision during peak migration season, Turkey will wield considerable

leverage as the vote approaches, enabling it to push for more and better

concessions from Europe. Though Brussels could attempt to delay its decision

until winter returns, doing so might cause the deal to unravel, since Ankara

will not house Europe's migrants for long without guaranteed terms.

The second question is more difficult to answer. With no end to the

Syrian and Iraqi conflicts in sight, Europe's migrant crisis will likely

continue for years to come. As the financial and social burden of Turkey's

migrant population grows, the government in Ankara will face mounting pressure

to increase its demands of Europe, including a tougher stance on the Kurdish

People's Protection Units in Syria and Continental support for a

Turkish-operated buffer zone at the Syrian border. Much of this pressure will

come from the nationalist elements that Erdogan's government depends on for

support. And because neither Erdogan nor Prime Minister Binali Yildirim has

tied his political career to the migrant deal's success, as Davutoglu did,

these demands may become less diplomatic as time goes by. Especially since

Britain's Brexit campaign and the rise of Europe's populist right are denting

Turkish hopes of ever joining the EU.

The UK situation

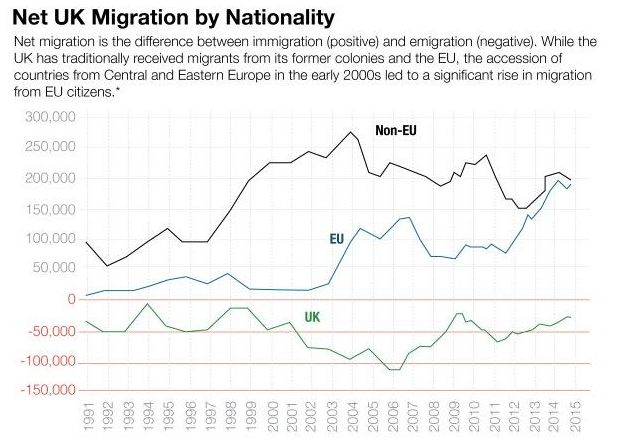

Between 1993 and 2014 the foreign-born population in the UK more

than doubled from 3.8 million to around 8.3 million," Oxford researchers Cinzia

Rienzo and Carlos

Vargas-Silva write. "During the same period, the number of

foreign citizens increased from nearly 2 million to more than 5 million.

This can’t all be laid at the EU’s feet. India and Pakistan are the

first and third largest sources of British immigration, respectively. But the

EU played a major part, as its rules restrict the ability of member states to

bar migration from other EU member states.

Between 2004 and 2014, when immigration to the UK really took off, the

percentage of migrants entering the UK from Europe spiked. It went from a

little over 25 percent to a little under 50 percent, which means that Europe

has driven a lot of the recent rise in the UK’s immigrant population.

There are basically two reasons for this. First, the EU starting

expanding in 2004 to include mostly post-communist countries in central and

Eastern Europe. These countries are poorer, which means that when they acceded

to the EU, their citizens were more likely to move out of them to find work in

richer countries such as the UK. Indeed, Poland is now the second-largest

source of immigrants to the UK, just behind India.

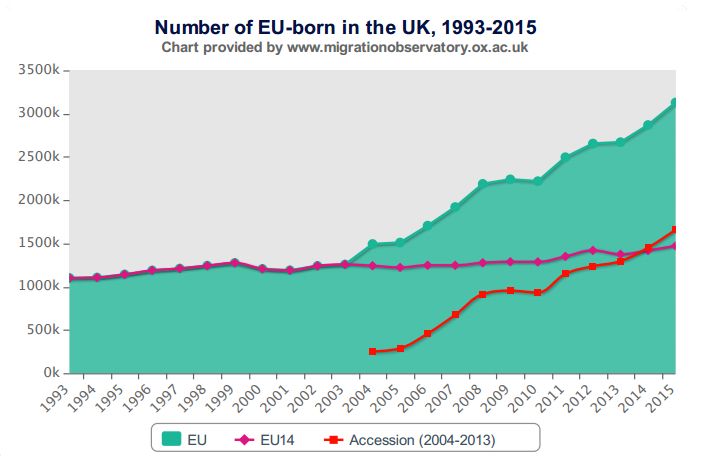

These "accession" countries were a major driver of European

immigration to Britain in the past decade, as this chart from Oxford’s

Migration Observatory shows:

Second, the 2008 financial collapse and subsequent eurozone crisis impoverished some historically wealthier countries

such as Spain, Italy, and Portugal. As unemployment rose in those countries, their

citizens started to look to other EU nations for employment opportunities. The

British labor market was relatively easy to break into, and lots of people

across Europe speak English, so it was a natural target for these southern

Europeans.

This, together with the continued influx of people from the

"accession" states, resulted in the number of EU-born people living

in the UK reaching over 3

million by 2015.

It also resulted in the EU becoming inextricably linked with immigration

in the minds of many British.

Over the course of the past 20 years, the percentage of Britons ranking

"immigration/race relations" as among the country’s most important

issues has gone from near zero percent to about 45

percent. Seventy-seven percent of Brits today believe that immigration levels should be

reduced.

As a result, anti-immigrant language has become politically potent. To give

one example, the UK Independence Party (UKIP), led by Nigel Farage, began life

as a small anti-EU party in the early '90s. But in the past 10 years, UKIP’s

poll numbers have soared: It got 4 million votes in the 2015 election, the third-largest national

vote total in the country.

At the same time, the center-right Conservative Party has also grown

more hostile to the EU and the increased immigration it represents, out of both

genuine conviction and a sense that catering to anti-European sentiment is good

politics. Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron, who supports remaining in

the EU, is opposed by about half of his own party’s members of

Parliament. Perhaps the most famous Leave supporter, aside from Farage, is

Boris Johnson, the Conservative former mayor of London.

Farage and the Johnson flank of the Conservative Party are the reason

Brexit happened.

Because they believe (correctly) that Britain can’t radically reduce

immigration without leaving the EU, pushing Brexit became one of their top

priorities. As immigration has grown, so has their influence. This, along with broader

Euroskepticism fostered by the euro crisis, allowed them to push Brexit

onto the political agenda and ultimately force Cameron to hold a referendum on

it.

Hence why the Brexit vote might very well happen this year, as opposed

to happening several years ago.

What will happen if there is a

Brexit

There is no doubt the vote to leave the European Union will bring about

some profound changes to immigration and border controls.

Currently the border between Britain and France is bound by Le Touquet

agreement, which allows UK border controls to be based on the French side of

the channel. The arrangement has been blamed for the establishment of migrant

camps especially around the Port of Calais. Although the agreement is not

directly related to the EU, a Brexit vote is likely to see French politicians

less motivated to continue to arrangement, which is seen by some to benefit the

UK more than France.

A Brexit vote also could spark the possibility Ireland and Scotland

could hold their own independence referendums in the coming years.

Another economic consequence will be that a sharp fall in the pound

could fuel a sharp and damaging rise in inflation, helping push the U.K. into a

recession and force the Bank of England to raise rates. Whereby the combination

of a cratering pound, other financial-market volatility, and lengthy

uncertainty are expected to hurt exports and business confidence in many other

European countries.

If there were a Brexit Britain's decision would affect each of the

bloc's members differently. The countries that will be most damaged by the

split are listed below.

For updates click homepage here